Three priorities for the High-level Political Forum 2019

DI Director of Partnerships & Engagement Carolyn Culey sets out three key priorities for closing the gap between the poorest and the rest at HLPF 2019

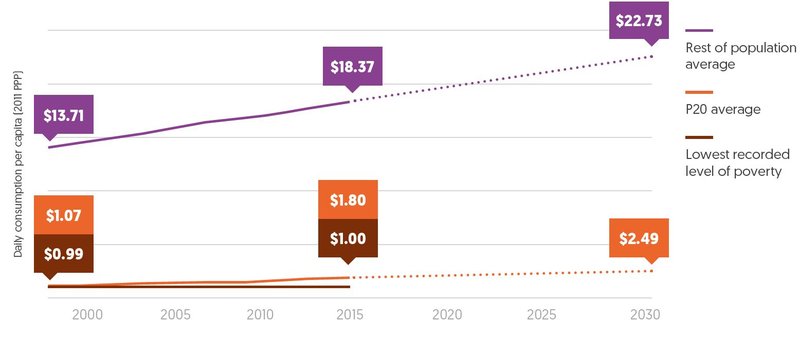

The daily income gap between the poorest 20% of people and the rest of the population has been growing, both globally and in most countries. If nothing changes, projections show that this gap will continue to grow up to 2030, threatening the achievement of SDG1: No poverty and SDG 10: Reduce inequalities.

The theme of this year’s High-level Political Forum , which opened yesterday in New York, is Empowering people and ensuring inclusiveness and equality – and the forum is an opportunity to discuss the action that must be taken to ensure that no one is excluded from progress. Our latest briefing Closing the gap sets out the current challenges and highlights three key priorities to help close the growing gap between the poorest people and the rest, and to raise the incomes and living standards of those who are furthest behind. These priorities are: invest in comprehensive, sustainable and interoperable civil registration and administrative data systems; reverse the recent decline in overall official development assistance (ODA) spending and increase the proportion allocated to least developed countries (LDCs); and increase domestic and international spending on human capital priorities.

The global picture of a growing income gap between the poorest 20% and the rest is repeated across most (87%) countries submitting voluntary national reviews at this year’s forum. A similar pattern can be seen across VNR countries in all income groups – the gap is growing in all high-income countries, all but one upper-middle income country, over three-quarters of lower-middle income countries and all but one low income country.

The briefing shows not only that progress has been slower for the poorest 20% of people, but also that those within the poorest 20% who are furthest behind, living at the lowest recorded level of poverty, have seen negligible progress over the past 15 years. Unless urgent action is taken to close the gap and raise the incomes of the poorest and most marginalised people, the Agenda 2030 pledge to leave no one behind risks becoming little more than empty rhetoric.

But poverty is about much more than income. Closing the gap follows a range of gender-disaggregated indicators (the share of the population aged over 21 who have completed at least secondary education, under-five mortality, and the share of children aged under five who are stunted). These show that the poorest 20% start from a low baseline and experience slow progress. Compounding this inequality, the rate of progress of the poorest 20% is slower than the rest of the population on some indicators, so the gap is widening. On other indicators, the gap remains broadly the same.

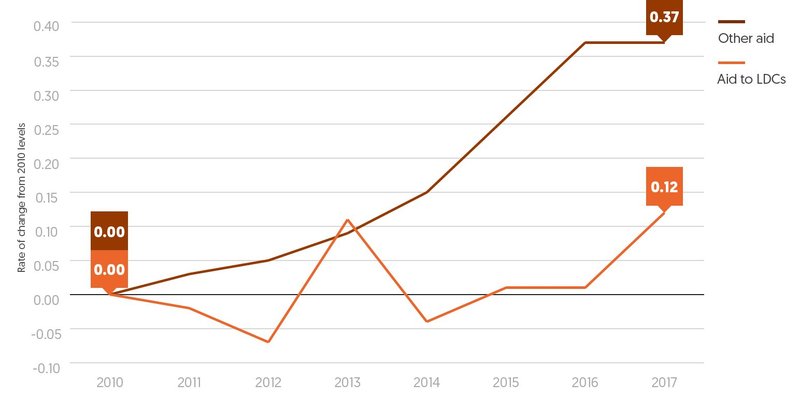

Closing these gaps between the poorest 20% and the rest requires a concerted effort to improve the targeting of both domestic and international resources towards the people and places that need them most. In the words of Agenda 2030, financing decisions need to start “reaching the furthest behind first”. But here too, we see a widening gap for example in relation to the allocation of ODA, where the data shows that gross ODA to LDCs has increased at a third of the rate of other aid since 2010, and less than half the rate of aid received by other developing countries and regions. Aid to LDCs from bilateral donors is particularly stark: levels were just 0.1% higher in 2017 than 2010, compared with 15% growth in bilateral aid to other developing countries and regions. Meanwhile, against the SDG 17.2 target for developed countries to fully implement their ODA commitments, global net ODA fell for the second year in a row in 2018 and only five donors met the 0.7% GNI target.

Recent analysis in a joint paper by ODI and DI examined the extent to which financing at the subnational level to healthcare and education by governments and donors targets the poorest regions. Our new paper looks at highlights the results in four countries submitting their VNRs this year for which data is available (Burkina Faso, Ghana, Rwanda and Tanzania) and finds that spending does not, for the most part, respond to the distribution of poverty in the country.

One of the central challenges in implementing the leave no one behind pledge is to identify the groups and individuals who are excluded from progress. The poorest and most marginalised are those most likely to remain invisible in official data and statistics. Children in the poorest 20% remain significantly less likely to be registered at birth and in 2015, nearly half of those aged under five in this group did not have their births registered. Governments cannot begin to ensure that everyone is included in progress if they do not know they exist in the first place. All countries face data gaps in their SDG reporting. The UK, one of the wealthiest countries submitting a VNR this year, was able to report against 74% of 244 SDG indicators which puts the challenge faced by the poorest countries in perspective.

To get SDGs 1 and 10 back on track, Closing the gap makes three key recommendations to actors at this year’s High-level Political Forum:

- Invest in comprehensive, sustainable and interoperable civil registration and administrative data systems.

- Reverse the recent decline in overall ODA spending and increase the proportion allocated to LDCs.

- Increase domestic and international spending on human capital priorities that most benefit the poorest people such as social protection, education, health and water and sanitation, and ensure this spending is targeted towards the people and places that need it most.

For full analysis, read our briefing Closing the gap: priorities for the High-level Political Forum 2019

Related content

Priorities for the UK’s incoming Secretary of State Alok Sharma

As Alok Sharma takes office as Secretary of State, DI's Amy Dodd sets out key priorities for the UK and its global development agenda.

From review to delivery on the Global Goals – what should the immediate priorities be for the UK government?

On 26 June, the UK government published its Voluntary National Review measuring delivery against the Global Goals - but does it accurately capture progress?

Three steps towards an equitable tax agenda: Actions that should be adopted at the Addis Tax Initiative conference this week

Gregory de Paepe outlines three steps towards an equitable tax agenda that should be adopted at the Addis Tax Initiative conference this week