Exploring inequalities in the health sector in Kenya: Who’s left behind?

Not everyone in Kenya has access to the same healthcare opportunities. Using our Spotlight on Kenya, we analyse county performance in 3 health indicators

Not everyone in Kenya has access to the same healthcare opportunities. There are considerable differences in distribution of health outcomes, health determinants and resources across counties in Kenya. Health inequalities have significant social and economic costs to the extent that they limit people’s ability to realise their full potential in terms of participating effectively in community, social, economic and political life. So health inequalities have to be eliminated. But first budget holders and decision-makers at national and county level need access to quality data to better understand the causes of the inequalities, who’s left behind and the resources needed to ensure equality and equity. Citizens and civil society organisations (CSOs) also need quality data to hold the government to account to make sure the desired health outcomes are achieved.

Using our data visualisation platform, Spotlight on Kenya , we analyse county performance in three health indicators: one-year old children immunised against measles, skilled birth attendance, and use of modern contraceptives by married women.

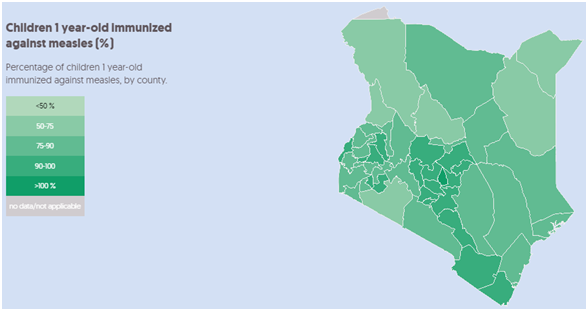

We find that the proportion of one-year old children immunised against measles is less than 75% in six counties, as illustrated in Figure 1. Coverage is relatively low in the northern part of the country too. All counties are expected to achieve and maintain as a minimum, immunisation coverage of 80% . But using the Spotlight on Kenya’s top and bottom 10 tables, we find that eight counties have not achieved this target. These are West Pokot, Mandera, Wajir, Samburu, Turkana, Narok, Marsabit and Tana River. West Pokot has the lowest coverage at 58% compared with Kirinyaga which has achieved the highest at 100%. So the eight counties left behind need greater support to achieve the desired minimum coverage.

Figure 1: Proportion of one-year old children immunised against measles

Source: DI, based on Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS) 2014 data

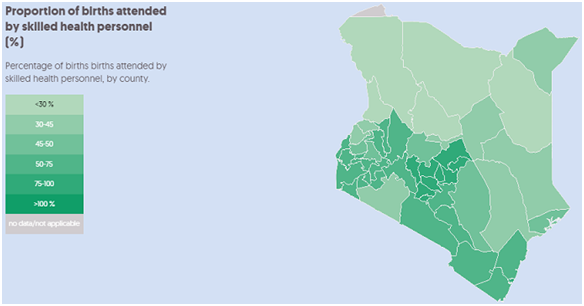

The proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel is less than 30% in five counties, namely Samburu, West Pokot, Marsabit, Wajir and Turkana. By contrast, over 85% of births in the top five counties – Kiambu, Kirinyaga, Nairobi, Nyeri and Muranga – are attended by skilled health personnel. Again a clear geographical pattern emerges here given that all the bottom five counties are located towards the northern part of the country, whereas all the top five are in the central region. What is more, the proportion of people in poverty is over 70% in all the bottom five counties except West Pokot (at 66%). By contrast, the proportion of people in poverty is less than 30% in the leading counties, except in Muranga (at 33%).

Figure 2: Proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel

Source: DI, based on KDHS 2014 data

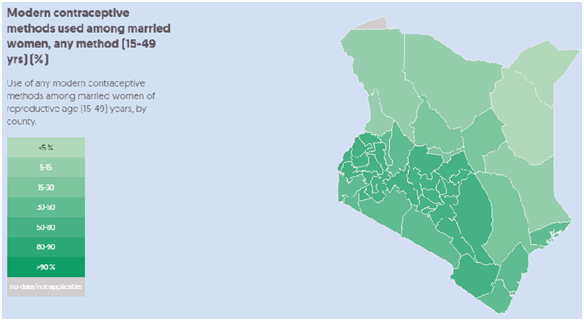

Less than 30% of married women (15–49 years) use modern contraceptive methods in nine counties as illustrated in Figure 3. These are Mandera, Wajir, Garissa, Turkana, Marsabit, West Pokot, Samburu, Tana River and Isiolo. By contrast over 60% of married women (15–49 years) living in the top 10 counties use modern contraceptive methods. Mandera has the lowest score of just 2% compared with Kirinyaga which leads with 76%. Apart from poverty, religion, cultural practices and low educational attainment contribute to poor uptake of modern contraceptive methods in Mandera, West Pokot , Wajir , and Garissa .

Figure 3: Proportion of married women (15–49 years) using any modern contraceptive method

Source: DI, based on KDHS 2014 data

Based on this initial analysis, it appears that a county is likely to be left behind in health if its geographical location is towards the northern or eastern parts of Kenya. Counties in these regions also have some of the highest proportions of poverty (above 55%), lowest educational attainment, perennial food insecurity as well as limited availability of health facilities and healthcare services compared with other parts of the country. Eliminating health inequalities needs development and investment into effective pro-poor public health interventions at national and county levels. Of particular concern in doing so effectively is the lack of publicly available data disaggregated at ward and village level to facilitate analysis of intra-county health inequalities and inequities. Collection, sharing and use of disaggregated data on health needs is critical to targeting interventions and should be prioritised by decision-makers, including through new collaboration with CSOs and other non-government data experts.

Related content

Priorities for the UK’s incoming Secretary of State Alok Sharma

As Alok Sharma takes office as Secretary of State, DI's Amy Dodd sets out key priorities for the UK and its global development agenda.

From review to delivery on the Global Goals – what should the immediate priorities be for the UK government?

On 26 June, the UK government published its Voluntary National Review measuring delivery against the Global Goals - but does it accurately capture progress?

Three priorities for the High-level Political Forum 2019

DI Director of Partnerships & Engagement Carolyn Culey sets out three key priorities for closing the gap between the poorest and the rest at HLPF 2019