How much has the UK spent towards its £11.6 billion climate finance commitment?

This blog explores data on the UK's climate finance spending and finds the government is likely to fall short of its 2026 commitment.

Introduction

Recently, the UK government triggered outrage among many by threatening to renege on its promise to provide £11.6 billion in international climate finance (ICF) for low and middle income countries by March 2026 , claiming that fully funding climate commitments would squeeze “out room for other commitments such as humanitarian and women and girls”. This led to even more anger as climate finance is supposed to be “ new and additional ”, not raided from the aid budget that has already seen severe cuts in recent years. And, as many civil society organisations have recently argued , climate finance is not a handout, but the correction of an injustice.

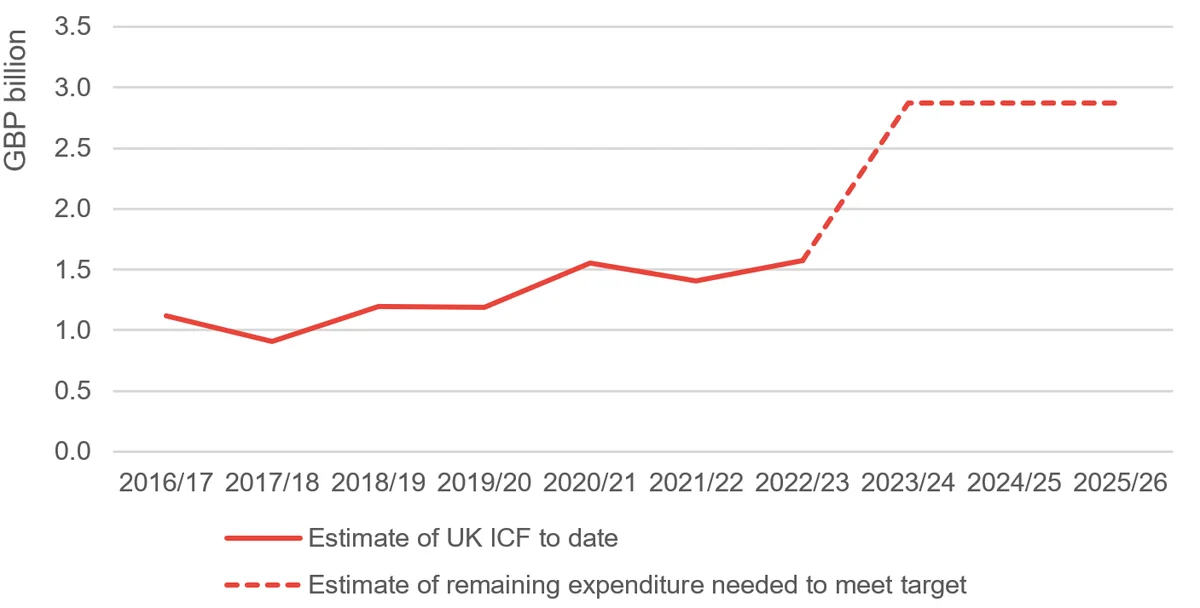

However, to understand the extent to which climate finance will divert aid from other priorities, it’s important to first understand how much has been spent toward the £11.6 billion commitment. This blog explores the data on this question and finds that the UK has spent as much as £3.0 billion on ICF between April 2021 and March 2023. This suggests that the UK would need to spend £2.9 billion each year on average between March 2023 and March 2026 to meet the £11.6 billion commitment. This is nearly twice as much as in any preceding year. In addition, our figures could be an overestimate, implying the gap is even larger.

If the UK funds all climate finance from its existing ODA budget, attempting to meet this target would certainly squeeze out other development priorities. The solution however is not to cut back on climate finance, but to actually make it additional .

According to media reports, the government has claimed that meeting the £11.6 billion target would mean that climate finance would absorb 83% of the aid budget from now to 2026. However, this figure sounds unrealistically high and appears to be based on a misunderstanding. In 2022, FCDO’s bilateral budget was around £4.5 billion. If this remains unchanged until 2026, FCDO’s total budget over this period will be roughly £13.5 billion, with 83% representing £11.2 billion. In other words, the government’s claim would only be correct if:

- FCDO’s bilateral aid remains largely unchanged

- All international climate finance comes from FCDO’s bilateral aid

- And we haven’t spent anything towards the target since 2021.

None of these conditions are likely to be true. A significant proportion of what the UK has counted as ICF so far has come from the its contributions to multilateral climate funds (mainly to the Green Climate Fund) and other government departments. Even if the ODA budget remains roughly the same until 2026, in-donor refugee costs are likely to fall significantly in 2025, freeing up a potential increase in FCDO’s budget.

This blog examines the remaining condition: how much has the UK spent so far towards the commitment? To answer this question, we examine data that the UK has reported to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), which includes variables that indicate whether transactions are counted as ICF, as well as annual reports from FCDO and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). The IATI dataset is not perfect. The UK is better than most countries at reporting data to IATI, but its data is nevertheless incomplete. There are also some (mostly minor) inconsistencies between these tagged transactions and data reported to the UNFCCC, as well as with the list of projects that the UK includes as climate finance on its own “ UK international climate finance results publication ” (see Annex 1). Notwithstanding these caveats, we find that the UK has spent as much as £3.0 billion towards the target so far. This means it would have to nearly double average annual ICF spend in the remaining years to meet the target.

Composition of UK’s ICF

There are two departments that account for nearly all of the UK’s ICF:

FCDO

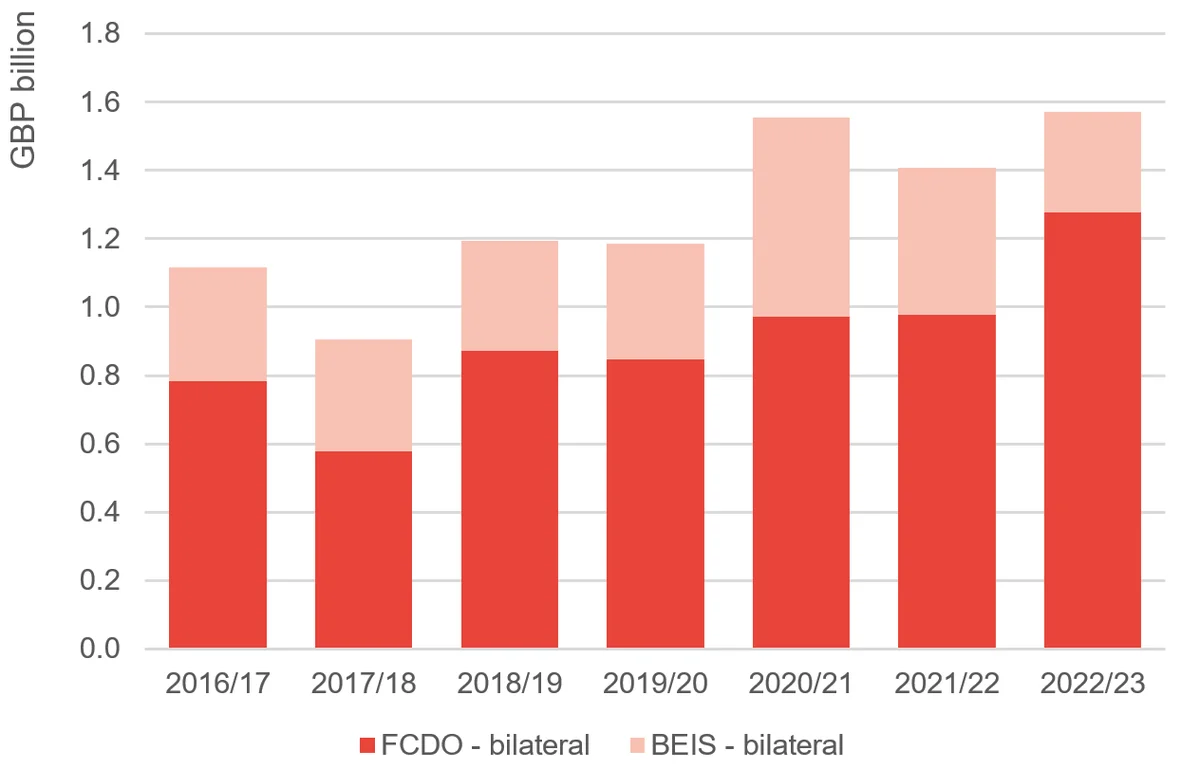

In 2021/22 and 2022/23, FCDO reported ICF worth £925 million and £661 million respectively through IATI. [1] However, we know that these figures are incomplete. In 2021/22, only 95% of FCDO’s ODA is recorded in IATI. In 2022/23, the figure is 68%, but we also know from World Bank Trustee reports that FCDO made a contribution of £264 million to the Green Climate Fund in that financial year. After adjusting for these factors, we estimate that FCDO spent as much as £978 million in 2021/22, and £1,278 million in 2022/23. Although there is considerable uncertainty around the latter figure, and it is a large jump relative to previous years, it is similar to the ICF budget that FCDO had recorded in IATI for 2022/23, of £1,289 million. This means that FCDO has so far spent as much as £2.26 billion towards the target.

Figure 1: High estimate of UK climate finance by financial year

to be added

Sources: DI analysis of IATI, World Bank Trustee Reports of GCF, FCDO and BEIS annual reports, UK Gov Main Supply Estimates

BEIS (now Department for Energy Security and Net Zero)

Unfortunately, while BEIS does report some data to IATI, it is not complete enough to be usable: according to IATI, only £171 million was spent by BEIS on ICF in 2021/22, and only £40 million in 2022/23. However, according to BEIS’s 2021/22 annual report , BEIS spent £431 million on ICF in 2021/22, a decline of 26% relative to 2020/21.

We are not aware of reliable source for BEIS’s ICF in 2022/23. However, according to government spending plans contained in the Main Estimates 2022-23 , BEIS were set to spend £292 million in that fiscal year. This is possibly an overestimate: in 2021/22, actual ICF spend was 5% lower than the initial spending plans. In addition, total ODA spent by BEIS fell by 41% between 2021 and 2022 according to UK Statistics on International Development , and applying a similar percentage change to ICF spending would imply ICF of £254 million. However, for a conservative estimate of remaining ICF spend needed to meet the target, we take the higher figure. This means that BEIS has so far spent as much as £723 million towards the target.

Figure 2: Conservative estimate of increase in expenditure needed to meet ICF target of £11.6 billion

to be added

Sources: DI analysis of IATI, World Bank Trustee Reports of GCF, FCDO and BEIS annual reports, UK Gov Main Supply Estimates

These figures suggest that there has been an increase in ICF spending since the target came into effect. This is despite steep cuts to the ODA budget in these years, owing to the reduction in the ODA/GNI target in 2021, and diversion of aid towards burgeoning in-donor refugee costs in 2022. Nevertheless, it has been far from sufficient to be on track to meet the £11.6 billion ICF commitment.

Additionality remains key concern

There is no agreed international definition of climate finance, and the extent to which it has been additional has been hotly contested. However, in the case of the UK, the question is relatively simple. So long as the UK treats the legally mandated ODA/GNI target (currently 0.5%) as a ceiling, then any ICF that counts towards that target will automatically displace other ODA. In other words, if ICF counts towards the 0.5% target, then it cannot be additional in any meaningful sense.

This must change. Recent cuts to the aid budget – brought about in part by the huge expenditure on hotels for refugees in the UK – should not be an excuse for abandoning its commitment to those most likely to feel the impact of climate change. As the UK seeks to rebuild its battered reputation as a development leader, one simple step would be to ensure that climate finance – which has a different philosophy and purpose to ODA – is additional to the aid budget, and that development and climate budgets are not pitted against each other.

You can download the annex of this blog to read more about the different sources of information about the UK's climate finance spending.

The data in this blog was updated on 18 September 2023.

Notes

- 1 This data was downloaded on 8 September 2023.

Related content

Reduced visibility? Opening up World Bank climate finance data

DI adapts World Bank data to allow users to identify which of their twenty thousand plus projects count towards the aggregate climate finance figures, and by how much.

New DAC data reveals the impact of the Ukraine invasion on aid

The rise in in-donor refugee costs associated with the Ukraine invasion means less money for LDCs. The latest DAC data shows they are paying the price for challenges elsewhere.

The Ukraine crisis and diverted aid: What we know so far

DI analyses emerging data on humanitarian and aid funding in 2022, finding that while Ukraine has received unprecedented funding, other crises are behind previous years