Latest trends in UK's aid spending to tackle malnutrition

DI explores the latest trends in the UK government’s spending on nutrition and looks forwards, considering the potential impact of Covid-19 on malnutrition and future aid investments.

This is the first in a two-part blog series that unpacks the latest analysis of investments to improve nutrition outcomes made by the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID).

The Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted how malnutrition acts as a threat-multiplier , with those suffering from malnutrition being more vulnerable to the disease. DI recently released its annual independent analysis of trends in the UK’s aid spending on nutrition . In this blog, we share the key findings, revealing how much is being invested and where it is going, and address whether DFID is meeting its existing commitments and living up to its promise of making nutrition a priority.

The findings highlight that the UK could still be on course to meet its nutrition financing targets, made at the Nutrition for Growth (N4G) Summit in 2013, despite the fact that spending on nutrition by DFID decreased slightly between 2017 and 2018. There was also a significant reduction in the number of nutrition-related projects in 2018, representing a return to pre-N4G levels. However, the findings reveal the UK government’s sustained efforts to mainstream gender into nutrition, which is recognised as vital to achieving equality of opportunity and equity of outcomes.

Progress on Nutrition for Growth (N4G) commitments

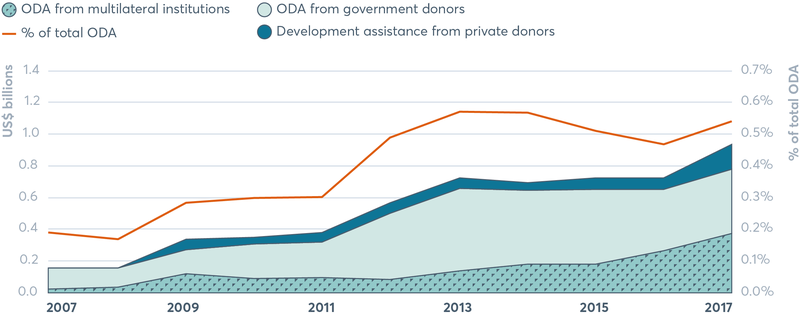

DFID has been providing leadership for the global N4G process since the first N4G Summit in London in 2013. Led by the UK government alongside other partners, the historic Global Nutrition for Growth Compact was endorsed by almost 100 stakeholders including governments, businesses, civil society organisations and others. The 2013 summit was followed by significant investments in international assistance for nutrition across the globe to 2017 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Levels of ODA for basic nutrition, from all donors, as a percentage of total spending, 2007–2017

Source: 2020 Global Nutrition Report .

DFID could be on course to meet its N4G commitments

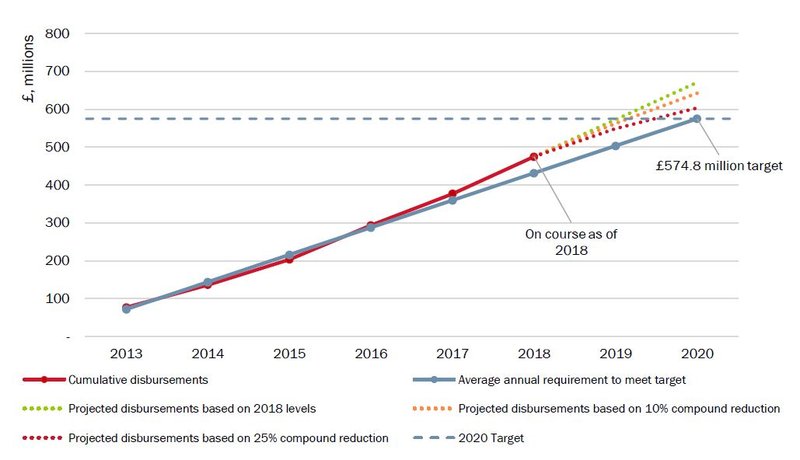

In 2013, DFID committed to tripling its investment in ‘nutrition-specific’ programmes (programmes which address the immediate drivers of nutrition) – which would amount to spending a total of £574.8 million between 2013 and 2020. To meet this target, DFID will need to spend £100.2 million over the remaining two-year period (2019 to 2020). If DFID were to maintain its nutrition-specific spending at 2018 levels, it would cumulatively spend £670.6 million in nutrition-specific financing between 2013 and 2020 – and therefore fulfil its commitment (see Figure 2).

However, maintaining that level of funding is not a given. There was a funding drop from 2017 to 2018. And, more recently, Covid-19 has introduced further uncertainties around the UK government’s aid spending and allocations to DFID have been falling .

Figure 2: DFID’s N4G commitments and cumulative nutrition-specific ODA disbursements, 2013–2020

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Creditor Reporting System (CRS) data, and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) National Accounts Statistics purchasing power parities (PPPs) and exchange rates.

Notes: Totals exclude matched funding. Disbursements are presented in 2018 prices and exchanged to £ from US$ using OECD exchange rates.

In 2013, DFID also pledged to match funding for new financial commitments for nutrition made by other actors, with the aim of encouraging other donors to provide additional funding on top of what was committed at N4G. This supports the scale up of nutrition-specific interventions.

DFID has not yet reached the ceiling of its matched funding commitment (£280.8 million), having cumulatively disbursed £145.0 million in matched funding so far.

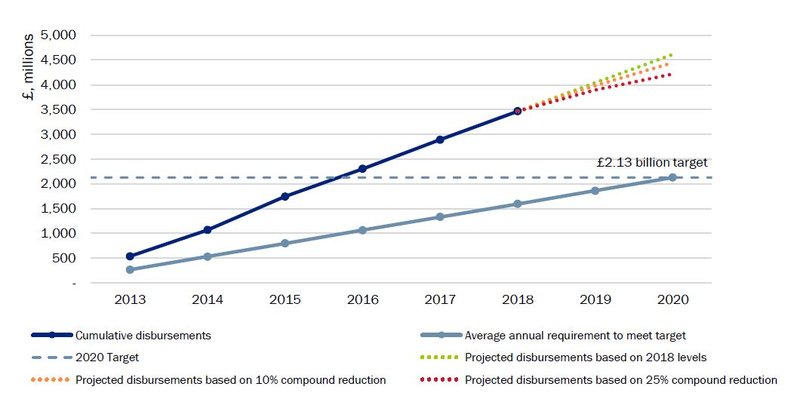

The UK government also committed to increase its nutrition-sensitive spending by 8 percentage points over the same 2013–2020 period. This would equate to spending a total of £2.13 billion by 2020. DFID has met this target — spending a total of £3.46 billion on nutrition-sensitive interventions between 2013 and 2018 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: DFID’s N4G commitments and cumulative nutrition-sensitive ODA disbursements, 2013–2020

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on DAC CRS data, and OECD National Accounts Statistics PPPs and exchange rates.

Notes: Totals exclude matched funding. Disbursements are presented in 2018 prices and exchanged to £ from US$ using OECD exchange rates.

Covid-19 could provide an opportunity to re-energise N4G stakeholders

Despite the optimistic view that DFID will reach or exceed its N4G targets, gaps remain. The N4G commitments are ending in 2020 and sustainable donor financing is required to ensure a steady flow of diverse funding to interventions aimed at improving nutrition outcomes around the world.

Since 2017, the level of collective donor support for financing nutrition has started to wane, and though we are yet to see the full scale of the impact of Covid-19 on funding, the situation is not looking promising. Global assessments find that current levels of nutrition financing are beginning to stagnate and remain far below the levels required to deliver on global targets. This does not bode well for the next N4G Summit.

Yet, with the outbreak of Covid-19, the call for increased investment in nutrition is more urgent than ever. Malnutrition affects our immune system, leaving us more susceptible to infection, and the socio-economic impact of the pandemic could, in turn, drive malnutrition globally – creating a vicious cycle . With this in mind, could the UK government leverage its reputation as a champion of global nutrition to re-energise existing stakeholders and inspire them to renew and expand commitments to end malnutrition?

As the Tokyo 2020 Olympics have been postponed due to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic; likewise the Tokyo N4G Summit has also been postponed to 2021. This would extend the deadline for stakeholders to deliver on their current N4G commitments and give a bit more time for a thoughtful approach to subsequent commitments.

Despite the uncertainties, Tokyo presents an opportune moment for stakeholders to renew and expand commitments for improved nutrition outcomes, as well as to strengthen the framework supporting mutual accountability around such commitments.

Read the full report: DFID’s aid spending for nutrition: 2018

This analysis was conducted as part of Development Initiatives’ work under the MQSUN+ consortium.

MQSUN+ is supported by UKaid through DFID; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. MQSUN+ cannot be held responsible for errors or any consequences arising from the use of information contained in this blog.

Related content

DFID’s aid spending for nutrition: 2018

As part of continuing efforts to track and better understand donor financing for nutrition, this report analyses the UK’s Department for International Development’s (DFID's) official development assistance (ODA) spending on nutrition-related projects.

Why equity is critical to tackling malnutrition

Harpinder Collacott and Charlotte Martineau explore how equity in food and health systems is crucial to reducing inequalities in nutrition outcomes.

The cost of achieving SDG 3 and SDG 4: How complete are financing estimates for the health and education goals?

We need to re-examine current financing estimates for achieving the SDGs if we are to leave no one behind. This background paper focuses on SDG 3 and SDG 4 – the health and education goals.