Aid in 2021: Key facts about official development assistance

Our factsheet highlights key analysis of global aid reported in 2021. It includes the latest DAC data on providers, recipients, sectors and climate targeting.

DownloadsIntroduction

This resource highlights key facts from DI’s analysis of global aid reported in 2021. Go directly to the Key facts .

We use the most recently available dataset (published in late December 2022). [1] The factsheet includes data on aid (specifically official development assistance – ODA) reported to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD DAC). [2] For more about OECD DAC data, see About the data.

The dataset allows us to analyse bilateral ODA (where one government provides ODA directly to another) and ODA disbursements from multilateral organisations (where organisations like the UN or World Bank provide ODA to governments). When analysing the data we use constant prices. We also use gross disbursements, rather than grant equivalent. This means the data we present may differ from that seen elsewhere. You can read about the benefits of this approach, and more detail about the data, later in this factsheet .

As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, it is estimated that the global poverty rate increased from 7.8% to 9.1%. [3] In 2021, over a third of the world’s people in need (around 306 million people) faced overlapping risks that included climate vulnerability, socioeconomic fragility and conflict. [4] ODA plays a critical role, particularly in the countries facing the biggest challenges where domestic resources are scarce and access to international markets is difficult. In this factsheet we analyse some ODA trends and unpack what the numbers tell us about where and how ODA is spent.

Key facts about aid in 2021

- Total ODA gross disbursements from DAC donors and multilateral organisations decreased in 2021 to US$205.6 billion, from US$209.6 billion in 2020 . Although DAC donors increased gross disbursements by US$7.5 billion (6%) in 2021 (to US$136.4 billion – the highest ever), disbursements from multilateral donors fell by US$11.6 billion (14%), meaning total ODA gross disbursements were lower than in 2020.

- India, Bangladesh and Sudan received the largest amounts of ODA in 2021.

- Health, humanitarian and infrastructure sectors received the largest amounts of ODA in 2021.

- Less than a third of ODA was disbursed to countries grouped as least developed and/or low income in 2021 (a fall of 2.0% from 2020).

- Total bilateral ODA marked as having a climate objective grew (up from US$27.1 billion in 2020 to US$28.4 billion in 2021) , driven by increases in adaptation finance.

- The proportion of ODA that governments provided as grants increased for the first time since 2018 (up from 78% in 2020 to 81% in 2021).

- An increased proportion of total ODA was spent within the country that provided it (i.e. was not transferred to the recipient country). This rose from 12.8% in 2020 to 13.9% in 2021.

Other resources

► Read more from DI on ODA .

► Visit our interactive aid tracker to track commitments and disbursements of aid and other types of global development finance.

► Share your thoughts with us on Twitter or LinkedIn

► Sign up to our newsletter

Back in 2022, Development Initiatives provided more in-depth analysis on a preliminary release of data from the OECD-DAC . This was supplemented by data drawn from the International Aid Transparency Initiative.

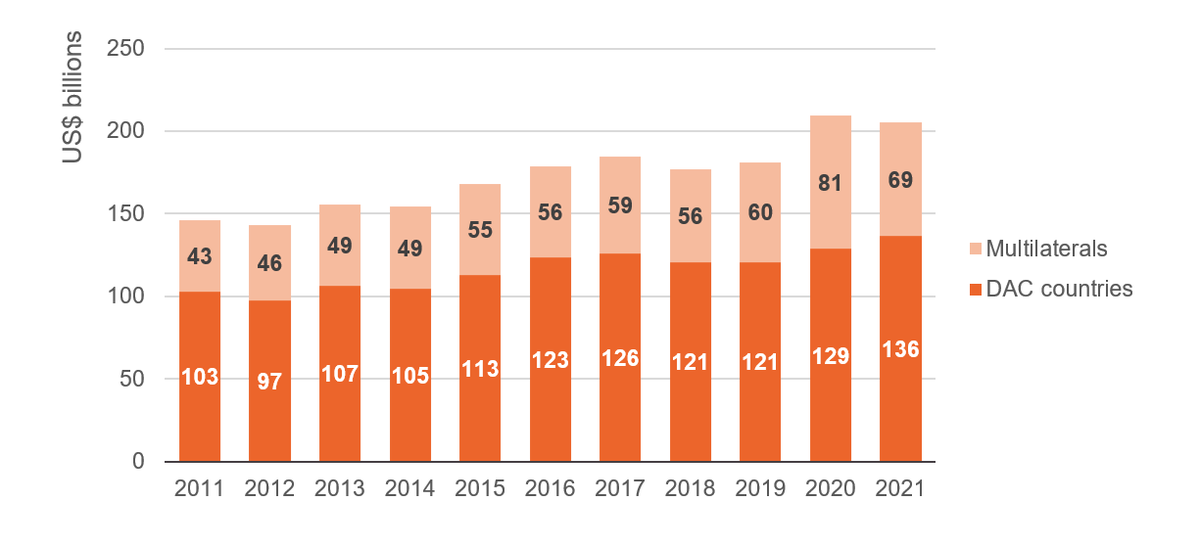

ODA from governments increased, while ODA from multilaterals fell in 2021

Figure 1: ODA from DAC countries and multilaterals (US$ billion)

| Year | DAC donors | Multilateral organisations |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 103 | 43 |

| 2012 | 97 | 46 |

| 2013 | 107 | 49 |

| 2014 | 105 | 49 |

| 2015 | 113 | 55 |

| 2016 | 123 | 56 |

| 2017 | 126 | 59 |

| 2018 | 121 | 56 |

| 2019 | 121 | 60 |

| 2020 | 129 | 81 |

| 2021 | 136 | 69 |

Source: OECD DAC data

Notes: Gross ODA disbursements from DAC donors and multilateral organisations, constant 2020 prices.

In 2021, DAC-member governments and multilateral bodies provided a total of US$205.6 billion in ODA. [5] This was US$4.1 billion lower than in 2020 – a fall of 2% (yet the total was still higher than other previous years).

Aid provided by governments (bilateral ODA) rose by 6% (US$7.5 billion) in 2021. Multilateral ODA disbursements (aid provided by multilateral organisations) fell by 14% (US$11.6 billion).

Large multilateral organisations that reduced their aid in 2021 included the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (by US$5.7 billion), the World Bank (by US$1.9 billion) and regional development banks (collectively by US$2.2 billion). In many cases these organisations had in 2020 provided especially high levels of support to governments affected by the economic impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic (particularly the IMF’s emergency financing facility).

India, Bangladesh and Sudan received the largest amounts of aid

Table 1: Top five recipients of ODA, 2021

| Country | Rank 2021 |

Rank

2020 |

2021

(US$ billions) |

2020

(US$ billions) |

Change

2020-21 (US$ billions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | 1 | 3 | 6,370 | 5,309 | +1,061 |

| Bangladesh | 2 | 1 | 6,082 | 6,442 | -361 |

| Sudan | 3 | 46 | 4,609 | 1,292 | +3,318 |

| Afghanistan | 4 | 5 | 4,238 | 4,190 | +49 |

| Ethiopia | 5 | 2 | 3,914 | 5,437 | -1,523 |

Source: OECD DAC data

Notes: Gross ODA disbursements from DAC donors and multilateral organisations, constant 2020 prices. For an expanded list, see Appendix 1.

In 2021, India received US$6.4 billion in aid from DAC-member governments and multilateral bodies – the largest total of any country, and an increase on 2020 of one billion. This was due to a US$1.7 billion increase in ODA provided by Japan (mainly in the form of loans for infrastructure projects).

Bangladesh received the second-largest total (US$6.1 billion), and Sudan received the third largest (US$4.6 billion). ODA to Sudan increased by 250% (US$3.3 billion) from 2020 – the biggest increase in ODA to any recipient country. This was due to:

- The IMF providing US$1.3 billion in budget-support loans to Sudan in 2021 (Sudan received no budget support from the IMF in 2020).

- The International Development Association (part of the World Bank) giving almost US$1.3 billion in grants to Sudan (compared with just US$100 million in 2020).

- The US increasing funding to Sudan by almost US$0.5 billion (primarily due to increased funding of the World Food Programme’s emergency work in Sudan).

Health, humanitarian and infrastructure sectors received the most aid

Table 2: Sectors receiving the most ODA, 2021

| Sector | Rank 2021 |

Rank

2020 |

2021

(%) |

2020

(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | 1 | 1 | 16% | 14% |

| Humanitarian | 2 | 3 | 13% | 11% |

| Infrastructure | 3 | 4 | 11% | 10% |

|

Governance

and civil society |

4 | 2 | 10% | 12% |

|

Business

and industry |

5 | 6 | 7% | 7% |

Source: OECD DAC data

Notes: Gross ODA disbursements from DAC donors and multilateral organisations, constant 2020 prices. See Appendix 2 for more detail.

In 2021, the sectors that received the greatest share of ODA from governments and multilateral bodies were health (16%), humanitarian (13%), infrastructure (11%), governance and civil society (10%) and business and industry (7%).

General budget support

In 2020, ‘general budget support’ received 8% of ODA – an unusually high proportion – due in part to the IMF’s programme of budget support lending in response to the economic impact of Covid. In 2021, general budget support decreased to 4%, due to the tailing off of IMF’s programme.

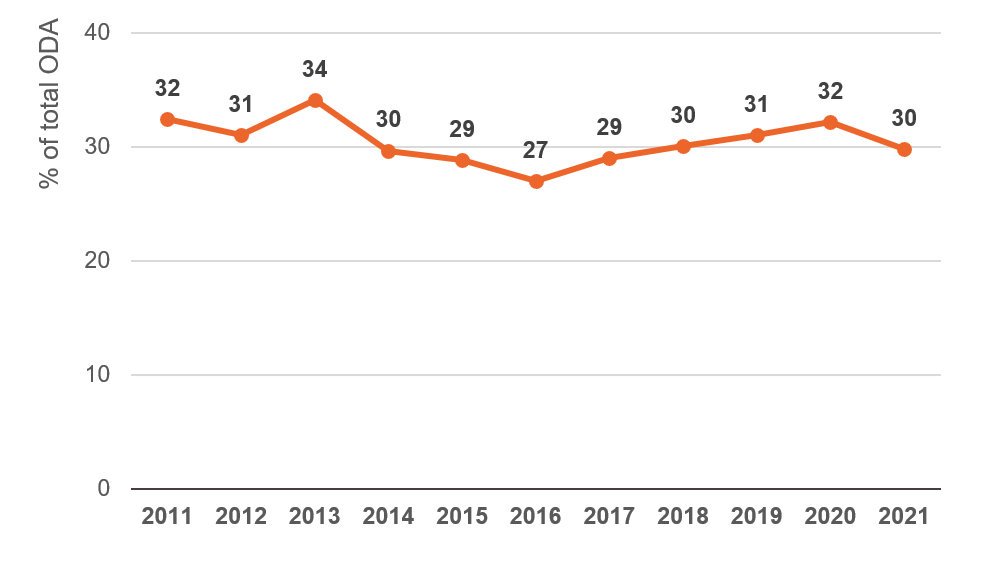

Less than a third of aid was disbursed to countries grouped as least developed and/or low income

Figure 2: ODA disbursements to countries grouped as ‘least developed’ and/or ‘low income’ (%)

| year | % | |

| 2011 | 32 | |

| 2012 | 31 | |

| 2013 | 34 | |

| 2014 | 30 | |

| 2015 | 29 | |

| 2016 | 27 | |

| 2017 | 29 | |

| 2018 | 30 | |

| 2019 | 31 | |

| 2020 | 32 | |

| 2021 | 30 |

Source: OECD DAC data

Notes: Gross disbursements from DAC donors and multilateral organisations, constant 2020 prices. This chart shows the total proportion of ODA disbursed to countries grouped as least developed countries (LDCs; designated by the UN) and/or low-income (LICs; assessed by the World Bank).

ODA to low-income countries and least developed countries

The share of ODA disbursements to countries facing the greatest challenges fell from 32% in 2020 to 30% in 2021. This grouping includes low-income countries (LICs; assessed by the World Bank to have the lowest income per person). [6] It also includes the least developed countries, (LDCs; designated by the UN as those “facing severe structural impediments to sustainable development […] highly vulnerable to economic and environmental shocks and have low levels of human assets”). [7]

ODA from governments to LDCs has remained steady (24.8% in 2020 to 24.2% in 2021). ODA provided by multilateral donors to LDCs fell from 43.9% to 40.8% (although the proportion of aid from multilaterals organisations to LDCs had been increasing since 2014, when the share was 36.7%).

ODA to other income groups, and ODA not allocated by country

Technically, ODA can be allocated to low-income countries, lower-middle income countries and upper-middle income countries (as defined by the World Bank). [8]

In 2021, however, all these income groups recorded a decrease in gross ODA disbursements from DAC countries and multilaterals. There was a US$7.6 billion increase in aid that was not allocated by country, and therefore could not be assigned an income group. Gross disbursements in this category have been increasing steadily for over a decade and now account for 32% of disbursements (and 41% of bilateral ODA from DAC countries).

An increase in unallocated ODA in 2021 was largely a result of both an increase in in-donor refugee costs in the US and an increase in aid channelled via GAVI (the vaccine alliance) to help respond to the Covid-19 pandemic. The increased aid via GAVI was mainly counted as bilateral rather than multilateral as it is given for a specific purpose.

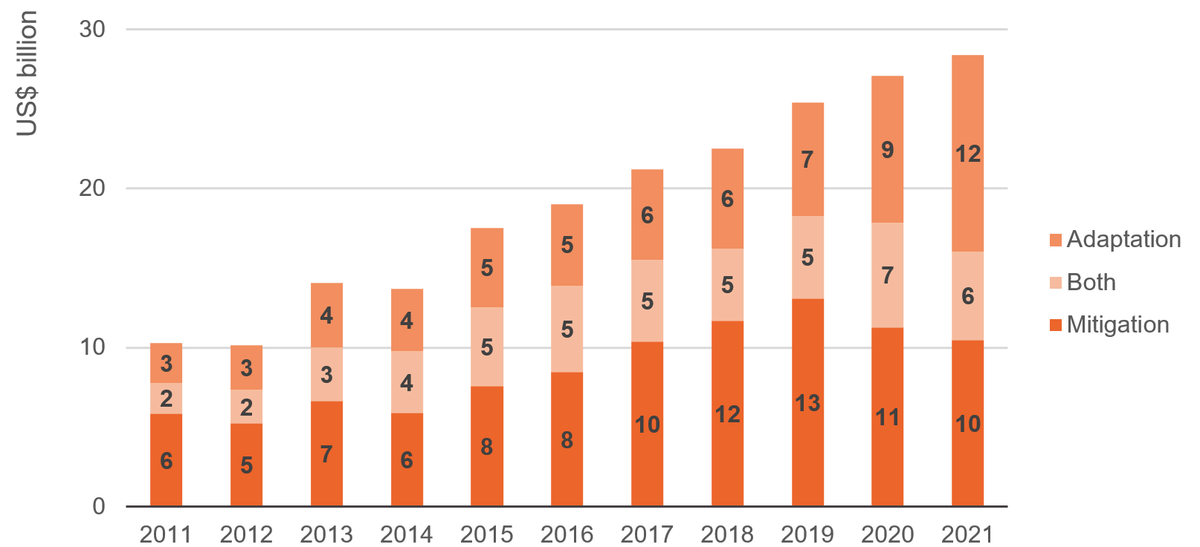

Total bilateral ODA marked as having a climate objective rose (driven by increases in adaptation finance)

Figure 3: ODA disbursements by climate focus from DAC countries (US$ billion)

DAC-member governments increased the amount of bilateral ODA specified as having a climate objective from US$27.1 billion in 2020 to US$28.4 billion in 2021, an increase of 4.8%. However, as gross bilateral ODA grew by slightly more (by 5.8%, from US$128.9 billion to US$136.4 billion), the share of bilateral ODA marked as having a climate objective fell slightly, from 21.0% to 20.8%.

Adaptation and mitigation

Climate ODA can be tracked using the Rio markers. [9] This lets us see whether ODA is targeted at either adaptation, mitigation or both. In 2021, adaptation-marked ODA accounted for 44% of climate-marked ODA. The volume of ODA targeted at climate mitigation fell slightly (from 41.6% in 2020 to 36.9% in 2021). The volume of ODA that was targeted at both adaptation and mitigation was 19.5% in 2021.

Aid for climate adaptation aims to reduce vulnerability to the current and expected impacts of climate change by maintaining or increasing resilience. [10]

Aid for climate mitigation aims to reduce climate change by stabilising greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere, promoting efforts to reduce or limit emissions and/or enhancing the capture and storage of emissions. [11]

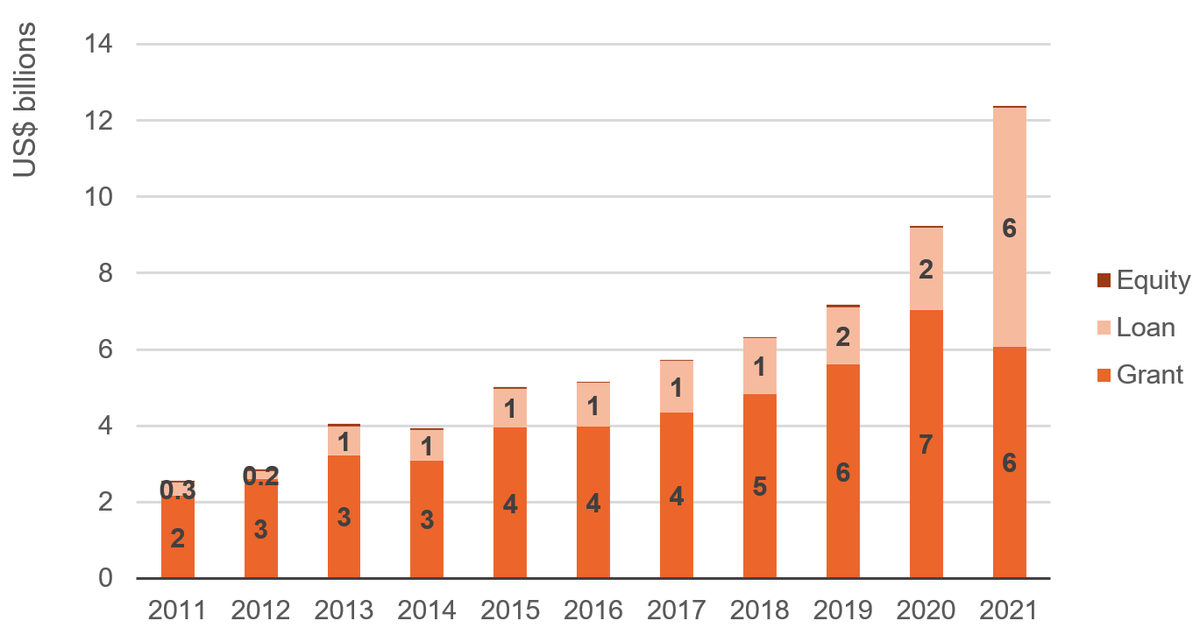

The increase in overall volumes of climate ODA was driven by growth in ODA targeted at climate adaptation, from US$9.2 billion to US$12.4 billion, (or from 7.2% to 9.1% of total climate ODA). In turn, this increase was due to loans rather than grants. Bilateral loan disbursements marked with an adaptation objective increased threefold (from US$2.1 billion to US$6.3 billion), whereas grant financing with an adaptation objective fell (from US$7.0 billion to US$6.1 billion).

Figure 4: Adaptation-marked bilateral ODA by flow type, 2021 (US$ billion)

Placeholder

| Year | Grant | Loan | Equity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| 2012 | 2.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| 2013 | 3.2 | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| 2014 | 3.1 | 0.8 | 0.1 |

| 2015 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 |

| 2016 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 0.0 |

| 2017 | 4.4 | 1.3 | 0.0 |

| 2018 | 4.8 | 1.5 | 0.0 |

| 2019 | 5.6 | 1.5 | 0.1 |

| 2020 | 7.0 | 2.1 | 0.1 |

| 2021 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 0.0 |

Source: OECD DAC data

Notes: Gross ODA disbursements from DAC donors, constant 2020 prices.

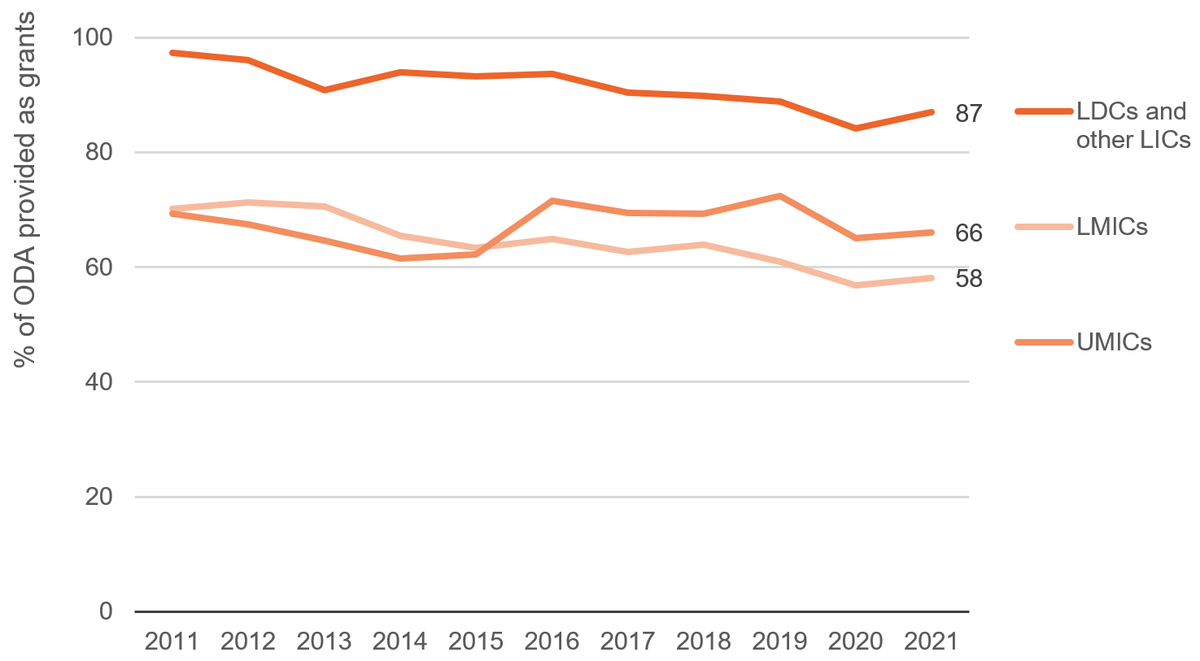

Bilateral aid provided as grants increased for the first time since 2018

Figure 5: Share (%) of DAC bilateral government ODA provided to each income group as grants

Placeholder

| Year | LDCs and other LICs | LMICs | UMICs |

| 2011 | 97.30687 | 70.09926 | 69.30871 |

| 2012 | 96.07097 | 71.34056 | 67.40603 |

| 2013 | 90.81504 | 70.52602 | 64.66336 |

| 2014 | 94.0037 | 65.50863 | 61.53875 |

| 2015 | 93.28093 | 63.32855 | 62.23589 |

| 2016 | 93.70572 | 64.91971 | 71.51154 |

| 2017 | 90.42288 | 62.68045 | 69.48392 |

| 2018 | 89.81402 | 63.93807 | 69.35774 |

| 2019 | 88.85174 | 60.98359 | 72.38912 |

| 2020 | 84.1441 | 56.87363 | 65.06019 |

| 2021 | 86.98134 | 58.11161 | 66.05163 |

Source: OECD DAC data

Notes: Gross ODA disbursements from DAC donors, constant 2020 prices. The LDC category refers to both ODA disbursed to low-income countries (LICs; designated by the World Bank) and/or the least developed countries (LDCs; designated by the UN)

Overall, the percentage of bilateral aid from DAC providers given as grants increased from 78% in 2020 to 81% in 2021. This was the first increase in the share of grants in bilateral aid since 2018, but the share remains lower than in any year since 2006 (before which data is less reliable). The increase recorded in 2021 was common to all income groups; in particular, the share of bilateral ODA given to LDCs and other LICs as grants was 84% in 2020, but increased to 87% in 2021.

However, loans that were granted declined in their concessionality. Using the DAC’s (highly contested) method of measuring concessionality, [12] the average grant element of loans to LDCs decreased slightly from 74.9% to 74.1% between 2020 and 2021.

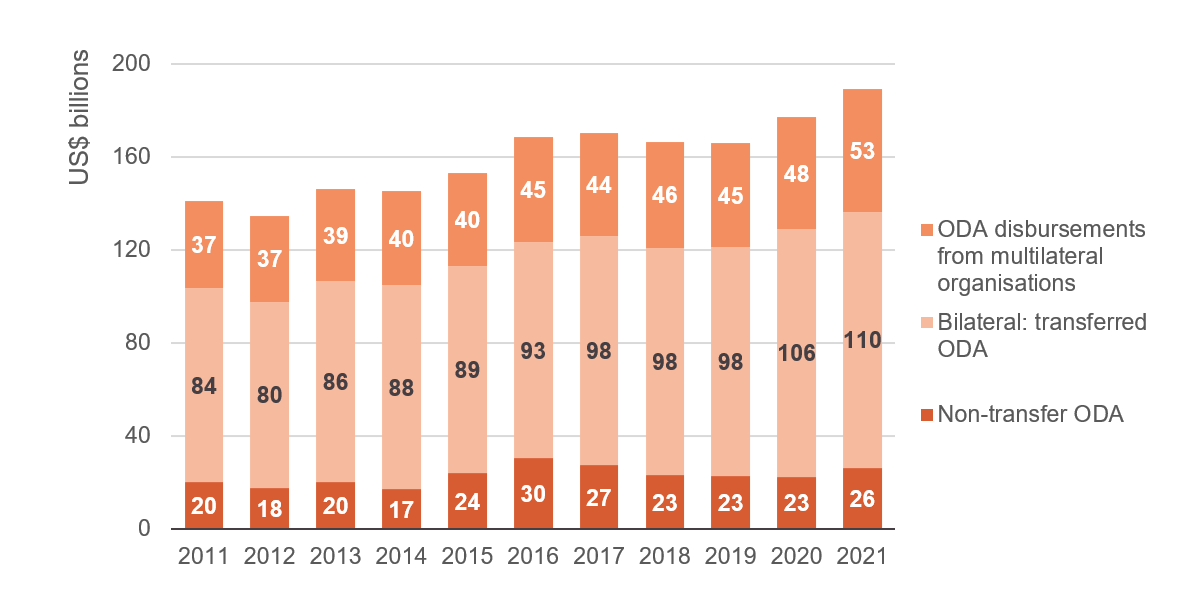

An increased proportion of bilateral ODA was spent within the country that provided it

Figure 6: DAC ODA disbursements, US$ billion: bilateral (transfer), multilateral and non-transfer

| Year | Non-transfer ODA | Bilateral transfer ODA | Multilateral ODA |

| 2011 | 20.07333 | 83.57723 | 37.23264 |

| 2012 | 17.81205 | 79.88738 | 36.86185 |

| 2013 | 20.40364 | 86.36951 | 39.20412 |

| 2014 | 17.21711 | 87.59821 | 40.34307 |

| 2015 | 23.91593 | 89.0697 | 39.82044 |

| 2016 | 30.35669 | 93.03903 | 45.18217 |

| 2017 | 27.43301 | 98.37589 | 44.22756 |

| 2018 | 23.05305 | 97.80467 | 45.53612 |

| 2019 | 22.9055 | 98.07689 | 44.79034 |

| 2020 | 22.56558 | 106.3247 | 47.98916 |

| 2021 | 26.19385 | 110.2205 | 52.6976 |

Source: OECD DAC data

Notes: Gross ODA, constant 2020 prices. Previous charts referred to ODA disbursements from multilaterals. By contrast, this chart includes multilateral ODA which refers to core contributions from donor countries to multilateral organisations. Hence, by definition, multilateral ODA is also ‘transfer’ ODA.

The proportion of total ODA spent domestically (also known as ‘non-transfer aid’) increased from 12.8% to 13.9% between 2020 and 2021.

Box 1

What does non-transfer aid include?

Non-transfer aid includes in-donor refugee costs, imputed student costs, in-donor scholarships, administrative costs and the promotion of development awareness. It also includes debt relief, whereby governments and organisations who provide aid are allowed to include debts that are rescheduled or forgiven as ODA. The amount that can be reported as aid is capped to the nominal value of the original loan. [13]

Key changes in non-transfer ODA: UK, US and Italy

The 2021 increase was partly driven by increases in in-donor refugee costs in both the UK and US.

In the UK, in-donor refugee costs increased by 66%, from US$805 million to US$1,339 million in 2021. This was partly due to an increasing number of asylum applications, but also to the higher costs associated with providing emergency accommodation to increasing numbers of people seeking asylum.

In the US, in-donor refugee costs tripled, from US$1,506 million to US$4,563 million in 2021. Expenditure on administrative costs in the US rose by 30%, from US$2.7 billion to US$3.5 billion.

Italy’s share of non-transfer aid more than doubled, from 8.3% in 2020 to 19.9% in 2021. This was primarily caused by cancelling debt held by Somalia (US$596 million). This was part of the ‘Heavily Indebted Poor Countries’ initiative and included debt relief on both past ODA loans and ‘other official flow’ (OOF) loans (the former would not be counted as net ODA).

About the data

About OECD DAC data

DAC members, which include all the main bilateral donor countries plus agencies of the EU, are obligated to report ODA data to these databases. In addition, all the main multilateral organisations voluntarily report their ODA commitments and disbursements. ODA data reported to the DAC is governed by a comprehensive set of reporting directives which means the data is standardised and comparable across different donors. Some countries which are not DAC members also report to the DAC, but many do not, (including large providers such as China and Brazil). For this reason, analysis is limited to DAC members and multilateral organisations.

You can find more information on the OECD DAC’s creditor reporting system database , and see the full data for download .

Key reporting changes

- A number of countries and organisations that reported ODA to the DAC in 2020 did not do so in 2021.

- Some (though fewer) countries and organisations that did not report ODA in 2020 did so in 2021.

- Moreover, GAVI reported all US$1.7 billion disbursements in a single CRS record (marked ‘preliminary’).

Additional data might be included in future updates.

Our analysis

We use constant prices. This means our analysis shows the changes in ODA without the impacts of inflation.

We use gross disbursements, rather than grant equivalent. The difference between gross disbursements and the grant-equivalent measure is how ODA loans are accounted for. Gross disbursements means the full face value of the loan is reported, whereas the grant equivalent measure means only a percentage of the loan is counted as ODA. This percentage depends on how concessional the loan is – the softer the loan, the higher the percentage counted as ODA. Gross disbursements are used in this analysis as that is more reflecting of the amount of money actually transferred in the year concerned.

This means the data we present may differ from that seen elsewhere.

Appendix 1

Table A1: Largest ODA recipients by volume in 2021, with change from 2020

| Country | Rank 2021 |

Rank

2020 |

2021

(US$ billions) |

2020

(US$ billions) |

Change

2020-21 (US$ billions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | 1 | 3 | 6,370 | 5,309 | 1,061 |

| Bangladesh | 2 | 1 | 6,082 | 6,442 | -361 |

| Sudan | 3 | 46 | 4,609 | 1,292 | 3,318 |

| Afghanistan | 4 | 5 | 4,238 | 4,190 | 49 |

| Ethiopia | 5 | 2 | 3,914 | 5,437 | -1,523 |

| Pakistan | 6 | 7 | 3,524 | 3,533 | -9 |

| Nigeria | 7 | 6 | 3,498 | 3,678 | -180 |

| Egypt | 8 | 23 | 3,496 | 2,232 | 1,264 |

| Kenya | 9 | 4 | 3,443 | 4,535 | -1,092 |

|

Democratic

Republic of the Congo |

10 | 8 | 3,422 | 3,529 | -107 |

| Jordan | 11 | 12 | 3,205 | 3,096 | 109 |

| Türkiye | 12 | 17 | 2,941 | 2,669 | 273 |

|

Syrian

Arab Republic |

13 | 14 | 2,757 | 2,875 | -118 |

| Indonesia | 14 | 9 | 2,651 | 3,442 | -791 |

| Tanzania | 15 | 20 | 2,630 | 2,472 | 158 |

| Uganda | 16 | 11 | 2,535 | 3,190 | -655 |

| Yemen | 17 | 24 | 2,448 | 2,133 | 315 |

| Somalia | 18 | 10 | 2,279 | 3,316 | -1,037 |

|

Viet

Nam |

19 | 18 | 2,271 | 2,542 | -271 |

| Mozambique | 20 | 16 | 2,230 | 2,709 | -480 |

Source: OECD DAC

Appendix 2

Table A2: Sector recipients of ODA, 2021

| Sector | Rank 2021 |

Rank

2020 |

2021

(%) |

2020

(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | 1 | 1 | 16% | 14% |

| Humanitarian | 2 | 3 | 13% | 11% |

| Infrastructure | 3 | 4 | 11% | 10% |

|

Governance

and civil society |

4 | 2 | 10% | 12% |

|

Business

and industry |

5 | 6 | 7% | 7% |

| Education | 6 | 7 | 6% | 7% |

|

Agriculture

and food security |

7 | 8 | 5% | 5% |

|

Budget

support |

8 | 5 | 4% | 8% |

|

Other

social services |

9 | 9 | 4% | 4% |

|

Water

and sanitation |

10 | 10 | 3% | 3% |

| Environment | 11 | 11 | 2% | 2% |

|

Debt

relief |

12 | 12 | 1% | 1% |

| Other | - | - | 18% | 16% |

Source: OECD DAC

Notes For more detail on sectors, see this OECD page: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=crs1

Downloads

Notes

-

2

DAC member governments are listed here: https://www.oecd.org/dac/development-assistance-committee/ . The figure also includes aid reported by international institutions with governmental membership that conduct all or a significant part of their activities in favour of development and aid recipient countries. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/9789264085190-11-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/9789264085190-11-en#:~:text=In%20DAC%20statistics%2C%20the%20multilateral,development%20and%20aid%20recipient%20countries .Return to source text

-

3

Carolina Sánchez-Páramo, Ruth Hill, Daniel Gerszon Mahler, Ambar Narayan, Nishant Yonzan, 2021. COVID-19 leaves a legacy of rising poverty and widening inequality. Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/covid-19-leaves-legacy-rising-poverty-and-widening-inequalityReturn to source text

-

4

Development Initiatives, 2022. The Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2022. Available at: /resources/global-humanitarian-assistance-report-2022/executive-summary/Return to source text

-

5

Throughout this factsheet we refer to gross ODA disbursements in constant 2020 prices.Return to source text

Related content

Tracking aid and other international development finance in real time

This interactive data tool lets you track commitments and disbursements of aid and other global development finance between January 2018 and April 2023.

The DAC debates: why aid measurement matters for development

The way we measure aid affects the type and quantity provided as well as our perceptions of it. Why are the DAC's rules controversial?

Trends in ODA through multilateral organisations

Donors are increasingly providing more earmarked than core funding. This factsheet looks at the current trends in ODA disbursed by multilateral organisations.