Catalogue of quality funding practices to the humanitarian response

A quality funding reference tool for policymakers and practitioners to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of programming.

DownloadsRead more on humanitarian financing

Our new report 'Falling short? Humanitarian funding and reform' provides the latest data on global humanitarian assistance, as well as progress on Grand Bargain localisation targets, cash and voucher assistance, and anticipatory action.

Read the reportIntroduction

Background and purpose

Discussions during the September 2019 ‘Progress Acceleration Workshop – Enhanced Quality Funding through Reduced Earmarking, Multi-year Planning and Multi-year Funding’ highlighted the need to collate and share evidence on the ways in which donors and recipients provide and use funding to better meet humanitarian needs. [1]

This catalogue on quality funding practices was first published in July 2020. [2] It presented a range of funding mechanisms identified by donors and recipients as providing ‘quality funding’ for humanitarian response. During their annual meeting in 2023, Grand Bargain signatories reaffirmed their commitment to increasing quality humanitarian funding until 2026 [3] and requested an update to the catalogue.

This updated version continues to fill the original evidence gap, and includes progress made on new initiatives and actions, such as locally and NGO-led initiatives. The focus on humanitarian funding mechanisms remains, though individual examples might support a broader crisis response across the humanitarian and development nexus.

The aim of this report is to provide a reference tool for policymakers and practitioners, both Grand Bargain signatories and non-signatories, with examples of the manner in which funding is and could be provided to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of programming. It is not intended as an exhaustive survey of quality funding practices but as an indicative summary of approaches to quality funding that can be added to.

Properties of quality funding

For the purposes of this report, Development Initiatives (DI) and the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) did not attempt to conceive a formal, technical definition of ‘quality funding’. Rather, we sought to collate examples of funding mechanisms or arrangements that were perceived by donors and recipients to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of responses and in so doing to identify the properties cited as contributing to the quality of this funding.

These properties included but were not limited to the funding duration and level of earmarking. Commonly cited properties that are referenced as contributing to the ‘quality’ of funding include:

- Funding duration: Captures the timeframe of the funding received and/or disbursed by a funding mechanism. Used to assess whether associated funding can be considered as multi-year, that is with a duration of 24 months or more based on the start and end dates of the original funding agreement. [4]

- Earmarking: The degree of earmarking of funding received and/or disbursed by a funding mechanism. Earmarking can occur at different levels geographically and thematically. A summary of different types of earmarking is set out in the annex to the Grand Bargain document. [5]

- Flexibility to adapt: Relevant to funding with any degree of earmarking, this captures the ease and speed with which implementers can move funding between budget lines, geographical borders or years. Key informant interviews have identified this as an important property to enable flexibility of funding despite relatively tight levels of earmarking.

- Reporting requirements: This refers to the frequency and extent of reporting on funding received or disbursed by the funding mechanism. Although the Grand Bargain workstream to ‘Harmonise and simplify reporting requirements’ focuses on this issue, humanitarian actors in this and past research frequently identified reporting as another dimension of quality for their funding.

- Manner and timeliness of disbursement: This captures the timing of disbursements in the funding process to assess how quickly funding was disbursed after signing an agreement, in which intervals, at what stage of the funding cycle and whether it was disbursed up front or in arrears. Where information is available, it includes an indicative range of funding volume associated with a funding mechanism.

- Accessibility: This includes a description of which implementing organisations were able to access the funding, in terms of their type (NGO (non-governmental organisation), UN, Red Cross, local and national actors) or size.

- Locally led: This captures whether local or national actors were easily able to access funding and had the decision autonomy on how to use it.

- Other funding conditions: This aspect captures other conditions on funding from or to the listed mechanisms that are not captured by the properties listed above, for instance restrictions on passing on funding or targets to be reached for a portion of the funding to be released.

Information on the properties outlined above is included for each funding mechanism only where available, and not all properties are relevant to all catalogue entries or best practice examples.

In recognition that the purpose of quality funding mechanisms ultimately is an improved humanitarian response with better outcomes for affected populations, we also requested information on cost-efficiency and effectiveness associated with the listed catalogue entries. It should be noted that this catalogue is largely descriptive and not evaluative, although we attempted to provide a balanced view of both challenges and benefits for each funding mechanism. The advantages, challenges and lessons described are based on user experiences drawn from written feedback and interviews. We referenced published evidence on and evaluations of quality funding mechanisms, where available, to substantiate this feedback.

Process of data collection

DI and NRC identified the funding mechanisms and arrangements that are included in this catalogue through a series of consultations with the co-conveners of the Grand Bargain Enhanced Quality Funding Workstream and an advisory group established to guide the research. In addition, we also reviewed existing literature on multi-year and unearmarked funding to identify other examples for inclusion in the catalogue. Where funding mechanisms were identified, DI and NRC conducted interviews and remote data collection and verification with the donors and agencies involved in the funding arrangement. Wherever possible we sought to reconcile the perceptions of both the donor and recipient of the funding and reflect their views of the advantages and disadvantages of the mechanism or arrangement.

Format and content of the catalogue

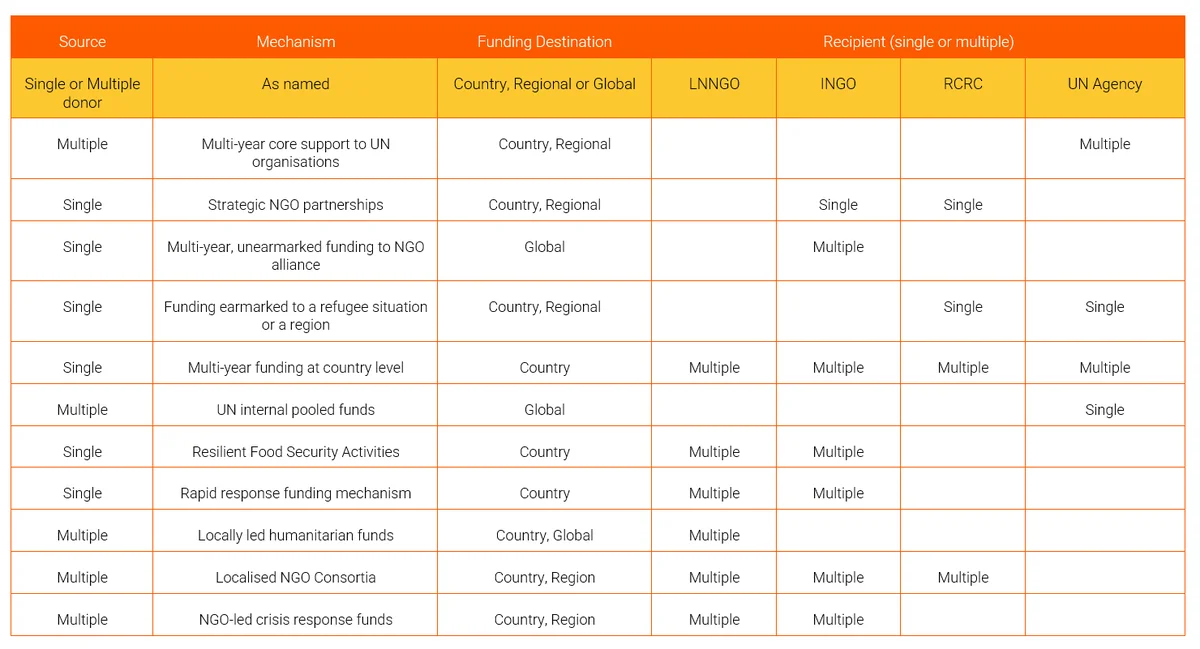

The catalogue includes 11 types of funding mechanism or arrangement, as well as best practice examples. Each catalogue entry includes:

- a description of the mechanism or arrangement;

- a description of how it operates;

- key features (earmarking, flexibility, conditions, reporting);

- advantages and disadvantages; and

- where identifiable, lessons from users of the instrument.

The catalogue includes the following funding mechanisms and arrangements:

- Multi-year core support to UN organisations

- Strategic NGO partnerships

- Multi-year unearmarked funding to an NGO alliance

- Funding earmarked to a refugee situation or a region

- Multi-year funding at country level

- UN internal pooled funding mechanisms

- Resilience Food Security Activities – Ethiopia

- Rapid response funding mechanisms for NGO action

- Locally led humanitarian funds

- Localised NGO Consortia

- NGO led finance mechanism

It also includes the following case studies:

- Start Network’s Global Start Fund

- UN OCHA’s Country Based Pooled Funds

- CERF’s support for Anticipatory Action

- The Red Cross Red Crescent National Societies Development Funds Ecosystem

- Spain’s Framework Agreements for Emergency Assistance and Humanitarian Action windows in NGO Framework Agreements

- UNFPA’s Humanitarian Thematic Fund

- Programme Based Approach

- Programmatic Partnership

- Concertación Regional para la Gestión de Riesgos (Consultative Group on Risk Management, CRGC)

- The NEAR Change Fund

- The Human Mobility Hub

Quality funding practice examples

Multi-year core support to UN organisations

What is it?

Core funding (also known as regular resources) consists of unearmarked contributions from public and private partners, given without restriction, allowing aid organisations to fulfil their mandates, across humanitarian and development programming if applicable. Core funding can be provided on an annual or multi-year basis.

In this catalogue entry, the focus is on multi-year contribution agreements between donors and UN organisations for global humanitarian activities. [6]

Examples collected included the Swedish, Canadian and Belgian governments’ core multi-year humanitarian funding to UN agencies.

How does it operate?

Funding is agreed for a multi-year period and is typically disbursed in agreed amounts annually. The volumes of the humanitarian funding agreements that the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs has with UN agencies range between SEK 760 million (US$75.14 million) and SEK 3.73 billion (US$368.79 million) across four years, while Belgium’s humanitarian multi-year funding agreements amount to €129.75 million (US$136.63 million) over three years. Of this funding from Belgium, €92.9 million ($97.83 million) is for UN organisations. Canada’s core multi-year support to UN agencies ranges from CA$6.0 million (US$4.61 million) over three years to CA$100 million (US$76.83 million) over four years.

Features (earmarking, flexibility, conditions, reporting)

- Core funding is fully flexible against the mandate of the recipient UN agencies. Allocations of core resources are made based on a set of pre-defined criteria and as agreed with the Executive Board, which is composed of member states.

-

There are relatively few conditions on the funding, but it may require that:

- Financial reporting and annual reports are submitted before the next year’s funding is released.

- Any unspent balances remaining after completing commitments can be reallocated to subsequent operations within the UN agency.

- Government donors may rely on the UN agencies’ own reporting, monitoring and evaluation systems, although the donor may request further information if required.

- Alongside core funding, there can in addition be a smaller amount of softly earmarked funding as part of the same funding agreement, e.g. for a particular region or for response to emerging crises. Although it comes under the same funding agreement, this funding is not considered as core funding due to its additional earmarking.

Advantages

- For recipients, this funding provides a range of well-traversed benefits, including predictable, sustained funding over a longer period. It enables longer-term planning for both recipients and donors.

- Recipients can use this funding strategically across their respective mandates to ensure maximum impact with donor funds, scale up sustainable solutions, invest in innovative approaches and adapt to changing situations in emergencies.

- Core funding can also be used as bridge funding for programmes without sufficient bilateral funding, as it is easily repurposed once additional bilateral funding comes through.

- Disbursement of the funding during the first fiscal quarter further increases its usability for UN agencies as it can then be used from the beginning of the year.

- For donors, this funding can help their progress towards meeting the Grand Bargain and other commitments. It can aid their reputation as a good donor and improve relationships with recipients.

- For both donors and recipients, multi-year funding can also mean reduced ongoing administration, although there can be more intensive effort required when the agreements expire or come up for renewal.

- Core donors enable recipient agencies to allocate resources to the most neglected and forgotten crisis and thus remove their own political decision making from the geographical allocation of their funding.

Disadvantages/challenges

- The quality of this funding does not always trickle down. While funding provided from donors to UN bodies is multi-year and fully flexible, funding from the recipient UN bodies to their implementing partners [7] may be in shorter-term cycles and tightly earmarked.

- Agreed amounts may not allow for inflation, which means the amounts received annually may decrease in real terms across the duration of the agreement.

- There can be a ceiling on funding, in that amounts given cannot exceed those agreed in the multi-year agreement.

- Due to its fully flexible nature and its ability to be repurposed swiftly where funding gaps arise, it can be challenging to report on the outcomes of core funding. While a donor can use evidence from additional UN reporting on the overall benefits of this type of funding to demonstrate to parliaments and taxpayers that it has delivered better assistance, core support can have less direct visibility than other funding vehicles. Implementing core support in multi-year agreements risks exacerbating these downsides.

- Core donors may require greater visibility of how or where their unearmarked funding to UN partners was allocated, for instance to be able to reference it during crisis- or country-specific pledging conferences. The challenge is that this can create tensions with the fully flexible nature of the provided funds.

- As funding is agreed for a multi-year period, a donor cannot suspend or withdraw funding during that time to respond to an action by the receiving institution that they do not agree with, for example, a change in policy direction or an instance of mismanagement.

Lessons from users of this instrument

- Donors and recipients are generally positive about multi-year arrangements, largely due to the significant benefits to recipient organisations. Multi-year agreements do generally require donors and recipients to have a strong partnership with a good level of trust and open communication.

- A key finding from a Belgian core funding policy evaluation is the need for UN partners to have dedicated human resources involved in proactive and effective engagement with core partners.

Box 1: In focus: Increasing the visibility of donor contributions – UNICEF’s Regular Resources

The Grand Bargain specifically calls for aid agencies to “increase the visibility of unearmarked and softly earmarked funding, thereby recognising the contribution made by donors”. [8] The 2019 Grand Bargain Independent Report noted “sporadic reporting on and progress against” this commitment. [9] Greater visibility of and transparency in the use of flexible and predictable funding has the potential to unlock increased volumes of such funding.

UNICEF’s Resource Mobilisation Strategy 2022–2025 introduced strengthened procedures and a new recognition and visibility approach for quality funding. These enable UNICEF to better recognise the funding it receives for regular resources (core funding) and to its thematic pooled funds. [10] The organisation has committed to provide funding partners with regular results briefs, including real-time updates of impact, that they can share with their constituents via social media announcements, press releases and presentations to parliamentarians.

In addition, UNICEF has carried out the following activities to enhance donor visibility:

- Conducting a survey with core resource partners to understand satisfaction with levels of visibility of their funding

- Creating a social media monitoring tool covering 34 public sector resource partners to identify gaps in visibility and recognition

- Co-creating recognition and visibility plans with core resource partners (Sweden and Germany)

- Organising field trips for donors to witness the impact of their funding and communicate this to their constituencies.

► Read more about this quality funding example: An evaluation of the Belgian core funding policy of multilateral organisations (2021)

Strategic NGO partnerships

What are they?

Strategic multi-year partnership agreements between government donors and NGOs to deliver humanitarian activities.

Examples collected included the Danish government’s strategic partnership with DanChurchAid, the Netherlands government’s block grant to the Dutch Red Cross, and the Spanish government’s two funding windows for NGO framework agreements for emergency assistance and the humanitarian assistance in protracted crises.

How do they operate?

The agreements operate over multiple years (all three examples collected were four-year agreements) and can be targeted at planned or ad hoc responses at a country, thematic or global level. Funding is typically disbursed annually – annual amounts in the examples collected ranged from €2.5 million to €15 million (US$2.63–15.8 million).

NGOs may be required to advise or seek approval from the government donor before spending the funding on ad hoc responses, depending on the amount.

Features (earmarking, flexibility, conditions, reporting)

- Earmarking can range from none (allowing the NGO to allocate the funding as it sees fit globally) to light earmarking to a country or emergency response and humanitarian activities.

- There can be flexibility to move funding between types of responses, and even to bring forward funding from the next year. There may also be a percentage (e.g. 10%) of funding that can be shifted within budget lines without needing donor approval.

-

There may be conditions:

- on the types or targeting of activities that can be undertaken; and/or

- requiring a report on the previous year’s activities before the subsequent year’s funding is released.

- There are typically light reporting requirements. Generally, an annual report is required (which can vary as to the required level of detail) and a final report at the conclusion of the funding may also be required.

Advantages

- Simplified processes around grant management, reporting and low levels of bureaucracy free organisational capacity within the recipient NGOs.

- Multi-year arrangements are very beneficial for recipient NGOs in particular. They allow long-term ambitions to be realised, as well as long-term thinking around addressing needs holistically. The timeframe also allows for planning and implementing a nexus approach.

- The partnerships can support localisation where funds are used to build the capacity of local partners and can support the NGO in establishing multi-year partnerships with local/national NGOs in humanitarian contexts.

- These partnerships can allow smaller government donors (e.g. Spain) to maximise the impact of their humanitarian funding by allowing them to work where the need is greatest, build the capacity of partners, and respond more effectively by working in multi-year cycles.

Disadvantages/challenges

- Can be administratively intense at the proposal/application stage.

- The standard of quality of proposals and reporting from NGOs can vary.

Lessons from users of these instruments

- These arrangements require a high level of trust between government donors and the receiving NGOs, and the continuous dialogue that these agreements foster provides for flexibility. A mutual understanding that effects will be long term is also required.

- DanChurchAid has transitioned into two-year agreements with its humanitarian partners. It has not yet extended agreements beyond this timeframe due to rapidly changing contexts.

- Focusing on small–medium-sized national or local NGOs could enhance the localisation impact of these partnerships. This would mean establishing equal partnerships over multiple years with local/national actors that are sustained in times of conflicts and emergencies.

► Read more about this quality funding example:

- Administrative guidelines for Denmark’s strategic partnerships 2022–2025

- An evaluation of the humanitarian assistance provided by the Netherlands (2023)

Multi-year, unearmarked funding to an NGO alliance

What is it?

Multi-year, unearmarked funding to an NGO alliance for global humanitarian activities. The example considered was the government of the Netherlands’ funding to the Dutch Relief Alliance, an alliance of 14 Dutch NGOs.

How does it operate?

The funding comprises a multi-year agreement with set annual disbursements to be allocated for broad areas of programming, which can be targeted at any humanitarian crisis. Areas of programming are defined by the NGO alliance, with reference to Humanitarian Response Plans (HRPs) and assessment of need. Members of the NGO alliance collaboratively agree on what projects should be funded within each of the broad areas of programming.

The Dutch Relief Alliance started in 2015 and is currently in its second block-grant of €370 million ($389.63 million), covering 2022–2026. The funding covers three streams, with funding levels for these agreed with government of the Netherlands: protracted crises constitute around 80% of the annual budget; acute crises constitute around 20% of the annual budget; and there is €3 million (US$3.16 million) for humanitarian innovation. Funds for protracted crisis responses (which run for at least two years) are disbursed annually. Funds for acute crises and for humanitarian innovation are disbursed through block allocations at the beginning of each year.

Features (earmarking, flexibility, conditions, reporting)

- Funding is softly earmarked for types of response but there are no restrictions on location or type of activity. For the Dutch Relief Alliance, funding is softly earmarked for protracted crises, acute crises and humanitarian innovation.

- The NGO alliance retains ownership of decision-making for projects and fund allocations.

- For the Dutch Relief Alliance, there is 25% flexibility within budget headings. Alliance members may also request advances on future annual allocations.

- The government of the Netherlands does not attach additional conditions to the grant but the Dutch Relief Alliance (DRA) itself is committed to provide quality funding based on equitable partnerships with its network of national partners. This translates into commitments that, firstly, that a minimum of 35% of the annual budget is used by national partners for implementation; secondly, that there will be systematic indirect cost recovery (ICR) sharing from 2024; and thirdly, that 5% of the budget is reserved for national partners’ capacity strengthening. The DRA is also committed to provide national partners with multi-year contracts where possible.

- Crisis modifiers [11] are included in all multi-year contracts to allow for fast and needs-based responses should the context change.

- For each protracted crisis response programme, an annual plan is required, with annual reporting using the 8+3 template. For acute crisis responses, a single annual report is required, covering all acute response programmes. Similarly, for innovation projects, a single annual report covering all projects is required.

Advantages

- For recipients, this arrangement provides a high level of flexibility and predictability of funding, with NGO Alliance members retaining ownership of decision-making for the identification of projects and allocation of funding within the agreement.

- DRA evaluation reports for 2022 shows that the flexibility of both the Alliance and the budgets it set was seen as a positive. [12] In some cases, this flexibility meant joint response could “change course where the needs were most precarious”, while in other cases, it allowed joint responses to “double the initial number of households served as a result of the 25% flexibility rule”. In instances of underspending, funds could be reallocated, especially to reduce the impact of Covid-19.

- The same analysis also showed that the crisis modifier was appreciated by local DRS partners in South Sudan and Somalia, enabling them to respond quickly to emerging acute needs.

- For donors, this funding arrangement allows for longer-term planning and a relatively low administrative burden.

- For donors, this funding can help their progress towards meeting the Grand Bargain and other commitments.

- For donors and recipients, this funding arrangement enables a close partnership between funder and recipient, as well as between recipients.

Disadvantages/challenges

- Working with an NGO alliance with a number of members with different structures, procedures and levels of funding can mean that reaching consensus for decision-making can take time. This means making changes or adaptations necessary to implement the alliance’s strategy can be slower than in individual organisations.

Lessons from users of this instrument

Multi-year agreements generally require donors and recipients to have a strong partnership with a good level of trust and communication, and this takes time to develop.

► Read more about this quality funding example:

Funding earmarked to a refugee situation or a region

What is it?

Funding provided to strategic partners to respond flexibly at the regional or refugee ‘situation’-level (i.e. refugee country of origin and host countries). Funding is softly earmarked to a specific refugee situation and corresponding appeal, or to a geographic region.

Examples considered included the German government’s funding to UNHCR for responses to refugee situations (encompassing country of origin and refugee hosting countries) or to geographic regions of UNHCR operations. We also considered funding provided through Canada’s Middle East Engagement Strategy to respond to crises in Iraq and Syria and to address the impacts or crisis in Lebanon and Jordan.

How does it operate?

The agreements provide funding softly earmarked to a refugee situation or to a geographic region of operations. Strategic UN and Red Cross/Red Crescent partners are able to determine where this funding is allocated within their existing response strategies and plans. These implementing partners can re-prioritise as situations and funding situations change, allowing the flexibility to re-allocate funding to emerging needs without seeking formal agreement from the donor. In specific cases, the agreements operate over multiple years. Of the two examples reviewed, Canada provided US$89 million over 2019–2021 in regional (softly earmarked) multi-year commitments, disbursed in annual tranches, to protracted crises in Iraq and Syria and to address the needs in Lebanon and Jordan. Of Germany’s total funding to UNHCR in 2023, around 80% (US$351 million) was softly earmarked for either refugee situations or UNHCR regions of operation. [13]

Features (earmarking, flexibility, conditions, reporting)

- Funding is softly earmarked to a refugee situation or geographic region of operation, giving partners the flexibility to determine where funding is allocated by country.

- Implementing partners retain the flexibility to re-allocate funding within the situational/regional response without seeking formal approval from the donor, although there may be an expectation that the donor is kept informed of significant changes.

- Additional conditionalities were not required by Canada or Germany.

- Annual reporting was required, though varied in level of detail. Financial reports are required from both partners, and Canada typically also requires the organisation’s annual narrative report. For narrative reporting, Germany relies on reporting provided through UNHCR’s Global Focus online system, which includes information on objectives, operations and outputs for each refugee situation.

- Recently, Germany has also been asking for a report on the final allocations of its flexible funding.

Advantages

- For donors, arrangements provide a reduced administrative burden as changes to location, project or activities do not require time-consuming negotiation or paperwork. This is perceived by donors as a benefit for recipients too.

- Enables recipients to use flexible funds where they are most needed, to be agile and respond quickly to changing needs on the ground.

- Recipients have reported that where multi-year arrangements are in place, these enable planning in the longer term, can help to establish greater stability and continuity in project management and can support the development of deeper relationships with key stakeholders, including the people in need of support.

- Reports from recipients indicate that these multi-year funding arrangements can also support monitoring and learning, at both programme and individual staff level, with the flexibility of funding allowing for changes to programming based on this learning.

Disadvantages/challenges

- For implementing organisations with regional multi-year funding as a relatively small proportion of overall funding received for the response, it is challenging to implement multi-year programmes given that the majority of other funding received is short term.

- Some donors, including Germany, require information on what their funding achieved as part of the response. Attribution can be challenging where flexible funds have been combined with other income streams.

- One donor also reported that more specific evidence is required on how the flexible and multi-year nature of funding provided to the response improves outcomes for affected populations, so maintaining or scaling up funding provided in this way can be justified.

Lessons from users of these instruments

- These arrangements are founded on well-established relationships between donor and recipient, which take time to develop.

- Trust between donor and recipient is key. Transparency and open communication were highlighted as being the foundation for this, with transparency noted as particularly important with regard to issues of integrity.

- Illustrating how funds have been spent is important; however, this should not result in excessive reporting or compliance requirements.

Multi-year funding at country level

What is it?

This funding instrument provides multi-year funding at the country level through one of the following:

- Bilateral agreements between donors and NGO, UN or Red Cross/Red Crescent partners for their operations in a specific country over multiple years.

- Provision by a donor to an implementing partner of a multi-year budget for the delivery of a specific set of outcomes in a crisis country.

Examples of this include:

- The UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth &and Development Office’s (FCDO) multi-year business cases in the majority of countries of operation,

- USAID/Bureau of Humanitarian Assistance’s (BHA’s) multi-year emergency assistance to NGOs in Ethiopia, Mali and Niger,

- Australia’s continued multi-year funding to UNFPA’s crisis response in Bangladesh, and

- Global Affairs Canada’s (GAC’s) multi-year funding to multilateral partners, and increasingly NGO partners.

How does it operate?

The bilateral agreements of multi-year funding at the country level are negotiated between the donor government and the respective implementing partner. The total funding amount for the multi-year period is usually agreed at the outset, though annual amount can be subject to revision following end-of-year reviews. Disbursement schedules vary by donor and can be quarterly, biannually or annually.

The FCDO has been a longstanding implementer of multi-year programmes and prioritises multi-year agreements with its partners wherever possible. Previously, multi-year programmes in crisis countries included funding a set of implementing partners to deliver a proposed set of specific outcomes within a multi-year budget, with timeframes matching the budget period. If a follow-up multi-year budget was authorised for the programme, there was flexibility in extending individual agreements for up to a year beyond the budgetary period.

In recent years, due to fluctuations to the UK aid budget, a larger number of multi-year partner agreements have included annual budgets within humanitarian programmes, meaning fewer multi-year funding commitments. FCDO remains committed to providing quality multi-year funding to its implementing partners and is working to return to a practice of multi-year agreements and funding. FCDO is also developing a strategy on local leadership that will consider how to ensure quality of funding is passed on by intermediaries to their downstream partners.

Timeframes for both forms of multi-year support at the country level range from two to five years. Due to usually large volumes of multi-year funding being provided, this funding mechanism is more accessible to large, well-established international humanitarian responders. For NGOs, it is similarly more likely to be provided to consortia than to individual organisations.

Features (earmarking, flexibility, conditions, reporting)

- Earmarking of bilateral multi-year funding is by design at the country level, but can also occur in addition for humanitarian purposes, or to certain thematic or sectoral areas (e.g. gender-based violence or food security). For grant agreements as part of multi-year country programmes, funding is earmarked to a detailed set of results specified in a logframe.

- There is no standardised reporting process for this funding mechanism; it varies by relationship between donor and recipient organisation. For multi-year contributions that are only softly earmarked to an implementer’s country operations, annual reporting on overall activities in-country tends to suffice.

- The flexibility of multi-year contributions to the country level varies, with additional levels of earmarking – if otherwise unearmarked or only for humanitarian purposes, they are fully flexible to use within the implementers’ humanitarian country response.

- For more tightly earmarked contributions, regular review processes and open channels of communication allow for changes to be made if necessary and justified, requiring exchanges between donor and implementer. This enables flexibility for partners in adapting programmes quickly to respond to crisis shocks without the need for a formal process, as long as the intended outcomes of the programme remain the same. Changes to any outcome-level results need to be formally agreed. This allows donors’ technical experts to guide programming towards desired outcomes on, for instance, resilience, localisation or accountability to affected populations. Some implementers however note that close, ongoing oversight at the technical level incurs a heavier reporting burden.

Advantages

- For multi-year programmes, having funding in place for a longer period enables the donor office to flex emergency response components if the crisis context changes while continuing to strengthen national systems for the delivery of essential services and social protection. There are no delays in applying for emergency allocations from the donor headquarters, given that funding for the country level is authorised in advance for multiple years.

- If multi-year funding at the country level is actively managed to support multi-year activities, it can lead to efficiency gains, for example through bulk procurement of supplies and reduced administrative costs for grant management.

- Multi-year funding at the country level when directly supporting multi-year activities provides staffing stability, continuity of services and greater trust in communities. If appropriate, it also enables multi-phase planning to work towards an exit strategy.

- Multi-year funding has the potential to foster both collaborative partnerships between funders and L/NNGOs, including women-led organisations, and shared commitments to achieving common goals.

Disadvantages/challenges

- Some donors are hesitant to commit too much of their humanitarian funding for multiple years in advance and prefer to reserve funding for unforeseen spikes in humanitarian need. This can be mitigated by building into multi-year grant agreements the ability to adapt programming or by including contingency funds.

- If multi-year funding makes up only a small proportion of implementers’ country operations, it is more difficult to translate it into longer-term planning and programming with the associated efficiency and effectiveness gains.

- Even with a multi-year timeframe, users highlight the need to be realistic about what humanitarian funding can achieve over a few years, as addressing structural deprivation requires a much longer time and broader resource base.

Lessons from users of these instruments

- Not all contexts are suitable for multi-year funding at the country level. Users identified this mechanism as most appropriate for protracted crises.

- Canada continues to encourage its partners to channel funding to local and national responders, and to include local actors in decisions related to the design, implementation and monitoring of projects. For example, GAC’s International Humanitarian Assistance NGO Funding Guidelines [14] were revised in 2021 to add a dedicated budget line for local partners’ overhead costs (up to 7.5% of direct project costs). Although no evaluation or monitoring reports have been completed specifically on this change, internal reviews suggest there continues to be strong support from GAC’s partners to maintain the overhead budget line for local partners.

► Read more about this quality funding example: External thematic evaluation of multi-year humanitarian funding provided by the UK government (2019)

UN internal pooled funding mechanisms

What are they?

Pooled funds internal to specific UN agencies, channelling unearmarked or softly earmarked funds received at the global level to different crisis responses based on humanitarian need. Examples considered were UNFPA’s Humanitarian Thematic Fund (HTF) for ‘Reproductive Health, Safety, and Dignity in Crises’, FAO’s Special Fund for Emergency and Rehabilitation Activities (SFERA), and UNICEF’s Global Humanitarian Thematic Funding (GHTF).

How do they operate?

Pooled funding allows UN agencies to deliver rapid and strategic responses to humanitarian need and provide assistance when humanitarian responses are underfunded. The flexibility and low earmarking allow UN agencies to act quickly and make allocations to country offices or partners that are most in need, including those that lack donor support and visibility.

Contributions to the funds may come from government or private sector partners (e.g. in 2023, UNICEF’s GHTF received 65% of funds from the public sector, and 35% from the private sector). Donors may provide one-off, annual or multi-year funding, and contributions are pooled, reducing transaction costs. The volume of contribution agreements varies: HTF agreements currently range from US$500,000 to US$1 million; SFERA agreements range up to US$14 million; and GHTF agreements range from US$30,000 to US$31 million.

When a response is required, a rapid quality assurance and approval process is undertaken, and funds are allocated quickly in the form of up-front grant funding or advances. Grants can be flexible in duration depending on the need, from short-term to multi-year timeframes (e.g. GHTF grants can last for up to four years).

Features (earmarking, flexibility, conditions, reporting)

- Funding is generally unearmarked or softly earmarked, for humanitarian responses or for target populations (e.g. women and girls, or children). Donors may allocate a grant to a programme for more strategic assistance to a specific crisis.

- There is generally a high level of flexibility to move funds between budget lines, activities, geographic areas or years. There may be some limits on flexibility depending on the type of funding allocated and any agreements with donors.

-

There can be a range of conditions on the funding, such as the following:

- It must target a certain population (e.g. the HTF must target women and girls, young people, people with disabilities and other groups who are marginalised and affected by the humanitarian crisis).

- Crises must meet set criteria (e.g. for part of its funding, SFERA requires a crisis to have been declared by UN OCHA and an international appeal, or a country to be in protracted crisis as defined by FAO’s early warning and food security information systems).

- Funds must be used against the targets and priorities set out in a particular appeal (e.g. the UNICEF Humanitarian Action for Children appeal).

- An annual report is generally required, covering the humanitarian response activities and results, as well as financial reports. This report may be provided to donors, governing bodies and the public.

Advantages

- Flexible funds allow agencies and their local implementing partners to react quickly to rapid-onset emergencies or the deterioration of existing crises, saving lives.

- Flexible funds also allow agencies to invest in preparedness and anticipatory action for early response through better risk analysis and the identification of high-return actions, which save lives and makes emergency responses faster and more efficient. The flexible pooled funds ensure a cost-effective response, which enhances the impact of donor contributions. Rapid early responses are more efficient, mitigating the impact of threats, protecting people and livelihoods, hastening the recovery of those affected and strengthening resilience.

- The flexibility of funding allows agencies to adjust activities and support according to the geographical and thematic areas of greatest need (see ‘Lessons from users of these instruments’ below).

- Pooled funding reduces the risk of a donor’s investment and allows for resources and responses to be tailored to underfunded emergencies.

- Administrative costs and reporting requirements can both be reduced through pooled funding mechanisms.

- The funds can allow for humanitarian responses to be more equitably based on needs, by reaching populations in small and/or forgotten crises or in underfunded sectors.

Disadvantages/challenges

- Pooled funds that make allocations to any part of the recipient UN agency’s global response may be less attractive to donors that want to give directly to specific responses or locations.

- The availability of resources limits the impact of the funds (e.g. SFERA would benefit from a greater degree of working capital).

- There can still be challenges in shifting the allocation of resources according to need, and additional effort is required to increase the fungibility of funding.

Lessons from users of these instruments

- Flexible funding to UNICEF’s GHTF and to FAO’s SFERA enabled both to invest in disaster preparedness and anticipatory action (see the 'In focus' section below), including better risk analysis and the early identification of impactful interventions.

- Seed funding provided by GHTF, SFERA and UNFPA’s HTF allowed for a swift response to kick-start operations in rapidly deteriorating contexts (e.g. in Ukraine) and to leverage additional funding from other sources. Notably, the large volume of flexible funding received by UNICEF for the GHTF in 2022 (US$784 million – three times 2021’s volume, and driven partly by the Ukraine crisis), showed that large volumes of quality funding can be swiftly provided and deployed to protect children’s rights in situations that are both rapidly evolving and featuring high levels of need.

-

During crisis responses, flexible funding enabled UNICEF’s GHTF and UNFPA’s HTF to focus on specific policy areas and gaps in the response:

- Both used flexible funding to mitigate gender-based violence. In response to flash floods in Uganda in 2022, HTF funds strengthened coordination among gender-based violence actors at district and national levels and facilitated the quick establishment of safe spaces for women and girls among internally displaced communities.

- Flexible funding also enabled UNICEF and UNFPA to deliver support in accordance with policy positions, such as the centrality of protection and accountability to affected populations – including those living with disabilities, and localisation.

- The flexibility of UNICEF’s GHTF also allowed for the allocation of funds to build pathways for impact and long-term results in fragile contexts in accordance with the humanitarian–development–peace nexus.

Box 2: In focus: FAO’s learning on the importance of flexible financing for anticipatory action during the 2023–2024 El Niño

In 2023, El Niño altered temperature and rainfall patterns around the world, contributing to hazards including floods in Eastern Africa and abnormally dry conditions in parts of Southern Africa and Central America.

Yet before such hazards materialised, FAO – in close coordination with governments and partners – had launched anticipatory actions in 19 countries at risk, providing support to approximately 700,000 farmers, herders and fishers who were already experiencing vulnerability. Anticipatory actions can work with these rural communities to continue producing food locally despite the hazards, safeguarding their food security.

Pre-arranged, unearmarked flexible funding has been critical in allowing the FAO to act quickly through the dedicated Anticipatory Action (AA) window of SFERA. US$11.4 million from SFERA was allocated for anticipating and mitigating the effects of El Niño.

SFERA-AA also played a catalytic role for other responders’ efforts. Following FAO’s AA activations (which in many countries were triggered in coordination with other organisations), the UN CERF allocated funding to scale up the assistance provided in Madagascar, Zimbabwe and Timor-Leste.

Preliminary empirical findings indicate that anticipatory actions were effective in helping to sustain local food production and protecting assets from hazards, with cascading positive effects on food security and nutrition.

Examples of Anticipatory Action

In 2023, when drought was forecast ahead of the postrera agricultural season in the dry corridor of Central America, FAO supported farmers experiencing vulnerability in the areas most at risk. They provided rainwater harvesting and water recycling equipment, drought tolerant inputs to produce short-cycle crops, and access to veterinary care. Based on preliminary assessments the funder reported that:

- The areas where support was provided saw improved animal health and increased agricultural production, despite the drought. In Guatemala, support to small-scale farmers with setting up kitchen gardens helped increase the size of cultivated area by up to ten times for some vegetables.

- In El Salvador, there were no assisted families with ‘poor’ levels of food consumption after the interventions. [15] Assisted populations were also less likely to use negative coping strategies than affected populations not receiving support. In Nicaragua, for instance, the Coping Strategies Index of assisted populations was less than half of the affected populations not receiving support. [16]

- The interventions also had an effect on dietary diversity. For instance, there were major increases in the consumption of the variety of meat, dairy, pulses and vegetables among assisted populations.

► Read more about this quality funding example:

Resilience Food Security Activities – Ethiopia

What are they?

In Ethiopia, Resilience Food Security Activities (RFSAs) are multi-year awards made by USAID/Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (BHA) to NGOs to support the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP) led by the government of Ethiopia. The PSNP aims to address the basic food needs of nearly eight million chronically food-insecure Ethiopians with both cash transfers and food assistance.

The RFSAs support the concept of a single, scalable safety net that addresses long-term chronic food insecurity and reduces poverty. This is combined with a shock-response contingency budget used to address acute needs that arise during the year among the clients covered by the RFSAs and the PSNP programme.

How do they operate?

USAID/BHA awards this funding to private voluntary organisations (which can include US and non-US NGOs) that are successful in a highly competitive request for applications in five-year cycles. The awards last for five years, with the funding disbursed through annual grants following a yearly workplan-approval process. Up to four awards are made per cycle, subject to funding availability.

The total amount funded through the awards is approximately US$110 million a year. USAID provides up-front funding to partners before shocks happen, which can be used in defined circumstances as set out in the cooperative agreement between the donor and partner. In the financial year ending 2023, amounts granted to organisations ranged from US$26.7 million (awarded to Catholic Relief Services) to US$49.2 million (awarded to World Vision).

Features (earmarking, flexibility, conditions, reporting)

- The funding is targeted at the programme level and is tightly earmarked to the successful private voluntary organisations under a prescriptive design.

- There is line-item flexibility at the award level, but there cannot be a change in scope (e.g. activity, geographic location) without prior USAID approval.

-

There are strict conditions on the funding, including the provision of:

- an indicator performance tracking table;

- a detailed implementation plan;

- a monitoring and evaluation plan; and

- a workplan-approval process.

- There are regular reporting requirements, with quarterly, annual and final budgetary reports required, as well as activity updates.

- Contingency budgets, in case of unexpected shocks, allow projects to pivot in response to context changes in less than a month.

Advantages

- This programme allows the donor a high degree of oversight of the programme, while contributing to a local, government-led social protection strategy that works to implement a scalable safety net.

- USAID has found this programme to be successful in strengthening resilience among rural food-insecure clients and protecting development gains. While the PSNP has an immediate focus on food security, it also supports longer-term outcomes around gender equity and women’s empowerment, livelihood support, nutrition and working with communities to become more climate resilient.

- The multi-year aspect of the awards offers partners predictability of funding, allowing them to plan further ahead and be more efficient, rather than operating in annual award cycles.

Disadvantages/challenges

The donor is closely involved at the output level, but this comes at the cost of increased donor and partner time dedicated to award management and reporting. This level of reporting is similar to other cooperative agreements that USAID operates.

Lessons from users of this instrument

Planning ahead on analysis, staffing and budget requirements for multi-year funding is important, as it can take a long time to get political and financial buy-in.

The contingency budgets were successfully used in response to the Covid-19 pandemic to mitigate food insecurity impacts in rural PSNP areas. As community food-security groups articulated needs, local governance structures requested use of the contingency budget. Partners notified USAID as part of the Covid-19 pivot plan approval process to effect contingency transfers of food. These were approved, and using the existing distribution and safety net system, new clients affected by Covid-19 are being enrolled into the programme for temporary support.

Rapid response funding mechanisms for NGO action

What are they?

These rapid response funding mechanisms operate within donor–NGO partnerships and enable rapid responses by local and/or international NGOs (INGOs) to sudden-onset crises, a deterioration of an ongoing crisis or in anticipation of a crisis. Rapid response funding mechanisms have swift approval processes and aim to provide flexibility and speed to respond to changing events.

Examples collected included the Swedish government’s Rapid Response Mechanism, USAID/BHA’s partnership with IOM to deliver a Rapid Response Fund in South Sudan and Abyei (one of several mechanisms of this type) and Start Network’s Global Start Fund. These are just a few of the rapid response modalities that exist to contribute to flexible funding and timely response.

How do they operate?

A donor undergoes a process with local or INGOs to enter a strategic or cooperative partnership (or, in the case of USAID/BHA, a partnership with the International Organization for Migration (IOM) that in turn supports partner organisations working in the region to deliver rapid responses). Through this process, the donor assesses the partner’s capacity and ability to implement rapid response projects. The duration of partnership agreements in the examples collected ranged from one to three years, or partners may be approved members of a network (e.g. Start).

The partnership funding can operate in different ways:

- An agreed amount can be paid from the donor to the recipient annually across the duration of the agreement.

- A proportion of the total amount funded through a partnership agreement may be tagged for rapid responses.

- There may be no ongoing annual amount paid, only funds paid out for specific rapid response projects as they arise.

When a sudden-onset crisis arises or an existing crisis worsens, an NGO can apply to the donor or partner agency through a simplified application procedure (e.g. an email, phone call or simple template, followed up by a fuller template/application) to use some of the already released funds to respond quickly to the emergency, or for new funds to be granted. Approval processes are streamlined (examples collected ranged from 24 hours to 7–10 days). For some mechanisms, approval can be granted at field or headquarters level (including for smaller amounts), while others (especially larger amounts) may need higher managerial approval, which may take longer.

Amounts released for the rapid response projects in the examples collected ranged from US$50,000 to US$750,000 (although Sweden can grant larger amounts with Head of Department approval). Most response projects are for a short period, ranging from one to six months, although Sweden’s mechanism allows for projects to be extended to up to twelve months in exceptional circumstances.

Features (earmarking, flexibility, conditions, reporting)

- Funds approved for responding to new or worsening crises are tightly earmarked for that purpose (this may be at country, organisational or project level).

- There is flexibility to use existing funds for new purposes as they arise, but they must be approved by the funder. There may also be flexibility to make minor changes within budget lines of the project itself without donor approval (e.g. up to 10%).

-

There may be conditions that the rapid-response programme:

- is concluded within a certain timeframe;

- uses the funding for only a sudden-onset or protracted emergency, or a humanitarian response – it may be precluded from venturing into longer-term development or disaster risk reduction projects; and/or

- shows a demonstrable benefit for the affected population within a specific timeframe.

- Funders have different requirements for reporting. Examples collected include requiring reports within a defined period after the start and end of the response project or requiring reporting on the project only through an annual report on the partnership as a whole. Reporting requirements may follow donor-specific templates.

- For some mechanisms, the majority of grants are made to local NGOs, providing access to quick funding for time-limited emergency responses, and capacity-strengthening support that will have lasting impact on their ability to respond.

Advantages

- Can be used to respond to fast-arising and moving crises.

- Can allow NGOs greater flexibility to be more responsive to emergencies. They can also provide greater funding to local and national NGOs, working with them to strengthen their capacity as well as providing an avenue for local partners to maximise the effectiveness of services delivered.

- Can allow donors to expand their geographic reach by working with local partners and coordinating with other agencies, meeting needs not met through other programmes.

- Decreases the risk of politicisation of aid and incentivises principled prioritisation by allowing operational agencies to independently direct pre-allocated resources across deteriorating crises. As such, there are potential policy-level benefits to this type of flexible funding (in addition to operational benefits in terms of timeliness).

Disadvantages/challenges

- In practice, for some mechanisms, recipients may not find approval from the donor particularly fast. The recipient may have to answer further questions from the donor before their request is approved.

- Where a donor is very principled or strict about what humanitarian funding can be used for, there may be tight rules that the funding can be used for only a pure humanitarian response, and not for anything that could be funded by development spending.

- The short timeframes inherent in rapid response mechanisms can in some circumstances counteract efforts to work more closely with local partners, even where there is a strong desire to do so, as the time available to fully include local partners in all phases of the project process is limited.

Lessons from users of these instruments

Rapid response arrangements are generally well regarded by the donors. The partnerships require a high level of trust between donor and recipient. For responses to become more rapid and flexible, some donors would need to increasingly empower the NGO to make decisions and decide for itself where to spend the funding.

Where the response funding is sought because of the worsening of a protracted crisis, a longer decision-making time may be appropriate, allowing donors and partners more time to collate information and make decisions. While a rapid response mechanism may be flexible in the way it operates, flexibility to extend the responses could help address needs that remains after the conclusion of a project. One donor extended the maximum duration for its response projects to address this.

In South Sudan, the BHA/IOM RRF relies on the involvement of national NGOs (NNGOs) as implementing partners. Through this localised approach, the RRF can efficiently reach populations in hard-to-access areas. This is achievable because NNGOs are deeply embedded in their respective communities and possess the capability to swiftly respond to any crisis with a fluent understanding of the local context. RRF remains the sole available funding mechanism for rapid emergency response for the NNGOs that are implementing partners within the country.

► Read more about this quality funding example:

- Web page of BHA/IOM’s Rapid Response Fund in South Sudan

- Swedish government’s guidelines for the Rapid Response Mechanism (2020)

Locally led humanitarian funds

What are they?

Locally led humanitarian funds are those where funding is provided to, and decided on, by local actors. [17] This allows organisations that have the contextual knowledge to make effective decisions about how money is spent to have the autonomy to do so. Examples that informed this entry include the regional Consultative Group on Risk Management fund (CRGC) in Central America, the Community Resilience Fund (CORE) in Nepal (not yet fully active), the NEAR Change Fund and the Syria-Türkiye Solidarity Fund.

How does it operate?

There are different models in operation containing the following features:

- Managed by a secretariat or selection committee, with an advisory or a governance body providing oversight. For example, six selected organisations in CRGC can administer funds to its 130 members across Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica. Every two years their governance responsibilities rotate.

- Members complete compliance checks before funding is disbursed. For example, The NEAR Change Fund members, which are based in 27 countries and have received US$1.5 million between them since 2022, apply for pre-approval, meaning that their organisation’s registration and financial reports are completed before an emergency is declared. They can then apply for grants ranging from US$150,00 to US$250,000, which are granted within 8 days of an acute crisis being declared. Further, there are often elements of local risk assessment or context analysis completed in advance so funding decisions are quicker.

- New funding opportunities are communicated to all members who are invited to formally express their interest. Those making decisions on who receives funds are not eligible for the same funding pool, and roles rotate through the membership.

- The funds are often hosted by a selected NNGO but this is for logistical purposes only. A separation is made between their role to disburse funds and their governance or participation role so that they do not unfairly influence decisions.

The CRGC invested over US$2.6 million over two years in pre-positioned funds to support emergency responses. The CORE fund in Nepal constitutes a consortium of 11 NNGOs that are creating a pooled fund for international, national and philanthropic donations.

Features (earmarking, flexibility, conditions, reporting)

- The flexibility and conditions of the funds’ allocations vary depending on any requirements the donor specifies for the overall pool.

- Fund allocations can be used flexibly for any necessary project activities within a specific response (i.e. recent or forecasted disaster) or sector.

- L/NNGOs report back to the secretariat or management committee, which then reports back to the relevant donors.

Advantages

- Pre-vetting and compliance processes completed before funding is disbursed mean it can be with L/NNGOs quicker than other funding mechanisms. The NEAR Change Fund has disbursed grants within 72 hours.

- Locally led funds prioritise local and national implementers that may have better access to areas and affected populations that are hard for international responders to reach, as showcased by the Syria-Türkiye Solidarity Fund’s response to the 2023 earthquakes.

- Reporting is required but varies on a case-by-case basis and is often much lighter than traditional funding mechanisms. Often, just one report is required at the completion of the project, outlining how the funds have been spent.

- Reduction in overall programme management costs can be an advantage, with overheads for locally led responses tending to be lower than for other, international mechanisms, work being focused within one region or country, and salary costs more often being adapted to the domestic costs of living rather than international pay scales.

- When allocations are flexible, L/NNGOs can adapt funding to changes in the context, rather than working within more rigid project frameworks.

Disadvantages/challenges

- There are only a small number of locally led funding mechanisms fully operational, which means very few local and national humanitarian actors are benefitting from the mechanism.

- Of those that are operational, funding volumes remain low, especially compared to the overall volumes of funding for specific regions or crises, or to international pooled funds.

- There is little evidence of locally led funding sources providing multi-year funding. Most pooled funds are designed for immediate responses.

Lessons learnt

Even though the locally led funds investigated under this entry focus on crisis responses, they often work towards a nexus approach. Respondents that were consulted to feed into this catalogue highlighted how the close attention paid to the whole range of the affected population’s needs leads to actions outside of traditional humanitarian response. Those implementing the funds have cited disaster risk reduction, advocacy, organisational capacity and resilience-strengthening actions completed alongside response to disasters.

Box 3: In focus: Innovative peer-funding mechanisms connecting refugee-led organisations

The Resourcing Refugee Leadership Initiative (RRLI) is a coalition of six refugee-led organisations (RLOs) that have established the Refugee Leadership Fund as RLO-to-RLO pooled fund – the first RLO peer fund of its kind.

Its members – Basmeh & Zeitooneh (Lebanon and Iraq), Refugees and Asylum Seekers Information Centre (RAIC) (Indonesia), Refugiados Unidos (Colombia), St Andrew’s Refugee Services (StARS) (Egypt), Young African Refugees for Integral Development (YARID) (Uganda) and Asylum Access (which also hosts the fund). The fund aims to support community-led responses in displacement situations and is supported by a number of private donors.

RRLI provides multi-year, flexible core funding to RLOs globally – disbursing over US$3.6 million since 2021. It provides this funding through two grant types: Strengthening Grants, which provide up to US$25,000 for smaller, newer RLOs, and Impact Growth Grants, which provide between US$100,000–200,000 to more established RLOs that can manage larger grants. The fund seeks to remove many of the preconditions that get in the way of RLOs accessing funding – for example, by allowing submissions in languages other than English and by waiving the necessity of RLOs having a bank account or legal registration before applying. It also seeks to facilitate connections between funders and RLOs that are often shut out of formal refugee response coordination systems. [18]

► Read more about this quality funding example: NEAR Syria-Türkiye Solidarity Fund web page

Localised NGO consortia

What is it?

Localised NGO consortia are similar to locally led humanitarian funds, but function as consortia of mostly local or national NGOs that are able to access funding based on predetermined criteria. They can involve international NGOs that have initiated the consortium or have a decision-making/funding management role.

Depending on consortium or programme arrangements, the funds received by the localised NGO consortium are released to local or national actors who make decisions on its use. When disaster strikes, these L/NNGOs can submit requests to access pre-arranged pools of money to address the consequences of the crisis at the local level in a timely manner, especially to reach those who can be overlooked by other actors.

Examples that informed this catalogue entry include the Somalia Nexus Consortium, the Humanitarian Operation and Innovation Facility (HOIFA), a pooled fund developed by the ‘Towards Greater Effectiveness and Timeliness in Humanitarian Emergency Response’ (ToGETHER) programme and Trócaire’s pre-positioned funding model for localised responses.

How does it operate?

- A secretariat or management committee, featuring a majority of L/NNGOs, is set up to manage the funds. For example, The Nexus Anticipatory and Emergency Response Fund, part of the Somalia Nexus Consortium, includes nine L/NNGOs and two INGOs (Oxfam and Save the Children).

- L/NNGOs who have pre-existing partnership agreements with German funders, and the four German INGOs who support them, have incorporated into their joint programme a flexible funding budget called HOIFA. It is earmarked only to humanitarian action, and its purpose is to test innovative approaches. This has been effective in releasing funds in emergencies to local organisations that cannot access funding from other international sources. Funded by the German Federal Foreign Office, through the ToGETHER Programme, grants are disbursed through country steering committees composed of leaders from local NGOs. [19]

- Trócaire has recently piloted a new model for humanitarian funding based on pre-positioned funding to support locally led responses in five countries: Sierra Leone, Malawi, Rwanda, Myanmar and Nicaragua. While Trócaire, an INGO, administers the funds, pre-vetted L/NNGOs have the decision-making power around when and how to use the funding. The model involves positioning a small, flexible amount of money with local partner organisations who can use it to respond to emergencies as they occur. Trócaire is using unrestricted income to finance the pilot. [20]

- The L/NNGOs that can benefit from the funds are selected based on the consortia’s requirements, geography (i.e. active in a district targeted by a programme) or due to a partnership with an INGO. Members complete compliance checks before funding is disbursed. Requirements might include having Emergency Preparedness Plans or other contingency planning in place, or more standard organisational capacity checks.

- Some of the consortia studied use a forecast-based financing approach to pre-emptively address needs to work with communities to mitigate losses and strengthen resilience to future shocks. Following an alert to a secretariat or management committee, funds are released. For example, the Nexus Anticipatory and Emergency Response Fund uses a forecast-based financing approach in order to pre-emptively address needs to work with communities in Somalia mitigate losses and strengthen resilience to future shocks. Funds are dispersed by Oxfam (Somalia Nexus Consortium member) in advance, allowing L/NNGO members to take ownership of decision-making on allocations to anticipatory action.

- The role of INGOs differs in each consortium, from solely reporting back to the donor, to monitoring any donor restrictions on funding allocations, to being a minority decision-maker.

Features (earmarking, flexibility, conditions, reporting)

- Funding to localised consortia is often softly earmarked for anticipatory action or humanitarian response in a given geographic context.

- Funding allocated by localised consortia to its consortium members is tightly earmarked for specific projects that respond to or anticipate humanitarian needs.

- Flexibility, funding conditions and reporting processes differ across consortia but there is a common and strong emphasis on local decision-making and streamlined compliance processes. This is to make funds available to a wide range of organisations and to ease administrative burdens as much as possible.

- Implementers provide simplified reports to the organisations managing the funding.

Advantages

- Localised consortia are often more flexible in adapting their response than other mechanisms as their funding is specifically designed to enable local partners to be more agile and responsive to changing and emerging humanitarian needs.

- There are many examples where funding was pre-arranged so it could be disbursed quickly and to shorten the time delay between the application for funds and them arriving in the L/NNGOs’ bank account.

- Forecast-based financing (to pre-emptively address needs to work with communities to mitigate losses and build resilience to future shocks based on a weather or seasonal/annual forecast) is an emerging feature of these localised consortia. Anticipatory actions, triggered with a forecast before a disaster hits, are therefore options alongside humanitarian response programmes that respond to disaster after its impact.

- Pre-vetting of consortium members means requests for finance are less likely to be denied than those made to other funding mechanisms, unless the circumstance does not meet the fund’s criteria of a humanitarian crisis. This arrangement provides some certainty for fund/network members that there is a pre-arranged pot of funding available to draw on in the event of a shock.

- The researched localised funding mechanism fill a gap in providing funds for L/NNGOs, who are unable to directly access funding from other international sources.

Disadvantages/challenges

- L/NNGOs who do not meet consortium criteria (programmatically, geographically or due to existing partners) remain excluded from this funding mechanism.

- There is arguably still a reliance on funding to be channelled through INGOs from international donors. The ongoing sustainability of localised funding therefore remains a challenge if it is conditional on those INGO’s engagement and fundraising.

Lessons learnt

- The strengthened decision-making role of local actors has progressed the localisation agenda.

- Users of this instrument have highlighted the benefit of learning together, as consortia foster a culture of collaboration. This approach has strengthened the examples given, with operational processes revised to capture shared learnings. For example, the Somalia Nexus Consortium’s early warning system’s triggers, criteria and proposal templates align with the Dutch Relief Alliance’s Somalia Joint Response (SOMJR-DRA) crisis modifier, and this continues to facilitate strong collaboration. Further, this emphasis on collaboration extends to government actors and local communities.

- Trócaire’s pre-positioned funds pilot suggests that the rapid availability of funding after a shock can result in L/NNGOs being able to leverage additional funding, for example through seed funding allowing them to complete rapid needs assessments. Their response speed can also strengthen their social standing with communities and local authorities.

► Read more about this quality funding example:

- Web page of the ToGETHER programme

- Web page of the Somalia Nexus Consortium

- Report on Trócaire’s pre-positioned funding for locally-led humanitarian action (2023)

NGO-led crisis response funds

What is it?

NGO-led crisis response funds refer to grant facilities that are managed by one or several NGOs to direct the funding received from one or multiple donors for the NGO-delivered crisis response. The initiatives reviewed as part of this example of quality funding dispersed funds to several partner NGOs (both national and international).

Examples of the NGO-led crisis response funds that informed this entry include the Sahel Regional Fund (SRF), the Human Mobility Hub, the Nabni-Building for Peace (B4P) Facility and the Global Start Fund. They all focus on attracting flexible and – where possible – predictable funding from donors. They then allocate this funding to NGOs so they can complement and fill specific gaps in crisis responses. This encompasses responses with a nexus approach, support for local actors, addressing neglected crises, and enabling rapid responses or cross-border activities to meet regional needs.

How do they operate?

NGO-led crisis response funds tend to be run by an independent management unit that is hosted within a single NGO. However, they often have a unique fund identity or brand that is separate from the host NGO’s brand. This is to avoid potential conflicts of interest in the allocation of funding and possible tensions when operating in complex, conflict-affected environments. In some of the reviewed examples for this case study entry, governance and funding processes were set up from scratch to match the fund’s specific mandate, such as supporting cross-border responses or local actors that are unable to access funding from other international sources. Governance models vary according to the funding mechanism; one or more INGOs are always involved while the inclusion of donors and local actors varies. [21]

Given that each of the reviewed NGO-led crisis response funds tailors their setup based on the response gap they seek to fill, funding eligibility and allocation approaches vary. Those facilities with a primary focus on localisation – such as the Human Mobility Hub or the Nabni-B4P Facility – only provide funding and other forms of support to local actors. Conversely, any NGO consortium involving both international and local actors and responding to cross-border crises in the Sahel region is eligible to apply for SRF funding. Finally, the Global Start Fund allocates funding to Start Network members with an existing operational presence in the crisis context within 72 hours of a crisis alert being raised, with funding decisions being made by Network members themselves.

Features (earmarking, flexibility, conditions, reporting)

- Donor funding to NGO-led crisis response funds is usually flexible within each mechanism’s mandate.

- In several instances, donor contributions to the funds reviewed were also multi-year (for example, FCDO has committed funding to the SRC until 2026) which enables better planning visibility and allows for multi-year allocations to be made.

- The degree of earmarking for allocations by NGO-led crisis response funds varies depending on their mandate but most funding is earmarked for NGO responses in specific country contexts. SRF is an exception as it supports cross-border activities with flexibility to shift funding across countries.

- Most of the NGO-led crisis response funds reviewed aspire to maintaining flexibility in their allocations so that their partners can easily adapt their activities in line with context changes.

- NGO-led funding facilities that focus on localisation provide additional flexibility to their local partners by co-designing activities based on the partners’ priorities and in line with their expertise.

- Reporting requirements vary across the NGO-led crisis response funds reviewed but are generally as light as possible while still meeting back donors’ reporting requirements, ensuring accountability, and enabling learning.

- The Global Start Fund pays great attention to the timeliness of its funding allocations; making funding decisions within 72 hours of a crisis alert being raised and transferring funds within 24 hours.

Advantages