Climate finance: Accounting and accountability

Inadequate reporting and tracking of climate finance data leads to reduced donor accountability. Ahead of COP27, this briefing examines five major issues.

DownloadsInadequate reporting and tracking of climate finance data leads to reduced donor accountability. Ahead of COP27, this briefing examines five major issues.

Introduction

In the pursuit of effective and fair climate action, ambitious climate finance pledges are welcome. Aiming for a substantial target should induce wealthy countries to provide more assistance to those with insufficient resources to avert, minimise and address the impacts of climate change, and hopefully incentivise greater action all round. However, targets are meaningless without a robust and transparent tracking and reporting mechanism. Pledges are difficult to track, and it is impossible to hold countries to account if their progress cannot be measured. Without a standardised approach to accounting and accountability, those most in need of climate finance will continue to be short-changed.

Currently, the data underpinning our understanding is limited at best and at worst, misleading. This undermines its transparency and accountability which are critical to delivering impact. It has also eroded trust between those who have committed to providing climate finance, and those who should be receiving it. That is why it is essential that at COP27, the tracking of these flows is higher up the agenda. Wealthy countries should not have the discretion to measure their commitments in the most politically convenient way. They shouldn’t be able to obscure the link between climate finance and other types of funding, so that it is impossible to tell what is new and what has just been relabelled.

A strong reporting framework that supports mutual accountability would be universally beneficial, helping ensure that bigger commitments translate into more spending, and allowing donors to coordinate their action. To drive effective and fair climate action, ambitious spending targets and pledges must be underpinned by a robust and transparent tracking and reporting mechanism. In advance of COP27, this briefing provides an overview of some of the biggest problems with existing climate finance data to highlight what needs to change in order to reach the next target. It focuses on the following five issues:

Issue 1: Disparate reporting methods

The issue: Lack of uniformity

When the US$100 billion goal was originally committed at COP15, insufficient attention was paid to how finance was measured. The current formal system of climate finance tracking and reporting established by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is complex, opaque, and demonstrably misleading. [1] National governments report to the UNFCCC using different estimation methods based on data reported to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) ( see Issue 3 ). Multilateral development banks (MDBs) also follow their own approaches. Some reporters disclose project-level detail, but others do not. Some reporters also define climate-relevant finance in different ways.

The sheer variety of stakeholders and the lack of any standardised approach means that there are a variety of reporting practices which, when combined, compound known inaccuracies and uncertainties. [2] [3] While reporting has improved since COP15, it is still far from consistent and is incompatible with the measurement of private sources of finance.

The way forward

The UNFCCC should aim to establish a single repository of comparable data on both international public and private climate finance as well as establishing internationally agreed data standards. This would allow users to assess the overall levels of climate finance in a consistent fashion, rather than needing to piece together secondary sources that are difficult to amalgamate, based on different assumptions, and not universally trusted by stakeholders.

Issue 2: Climate finance modalities

The issue: Lack of detail

The agreement to reach US$100 billion did not specify how it should be reached. As a result, countries count a diverse array of instruments towards their climate finance figures. It is legitimate to try to use all available tools to increase climate finance provision, but different modalities have different implications for the burden placed on the recipient and the effectiveness of climate finance. Loans, for example, can increase indebtedness, and so some countries may face a difficult choice between indebtedness and climate action. Often, the financial instrument used is simply disclosed as ‘other’, but even common classifications of grants versus loans hide finer details, such as loan concessionality. Consequently, the provision of climate finance in the form of hard loans to countries in debt distress may just replace one problem with another.

The way forward

When tracking climate finance, the UNFCCC should insist on more detail on the different modalities, types of support and varying means of implementation. When reporting loans, the terms of the loan should be provided, and where the modality is listed as ‘other’, a description of the exact instrument should be required. The introduction of the voluntary grant-element column [4] is a step in the right direction, but countries should be required to provide the full terms of the loans provided. This will ensure they are held accountable for actual fiscal effort as well as headline figures: if some countries provide more concessional loans than others, this needs to be recognised.

► Read more about donor commitments and tracking climate finance

Issue 3: Inflated estimates

The issue: Lack of accuracy

There is currently no agreement on the types of project that count as climate finance – or count towards the target – leaving countries free to decide what counts and by how much. Consequently, some countries count the full value of projects as climate finance, while others don’t count them at all. There is also inconsistency in the climate relevance that countries attribute to projects. Some countries count and report the full value of projects that don’t even mention climate goals in the project documents. [5]

These inconsistencies are in part due to the use of the OECD’s Rio Markers ( see Box 1 below ). They are used to track official development assistance (ODA) spent on climate finance by DAC members and indicate when a project has a ‘significant’ or ‘principal’ climate objective. The OECD are explicit in disclosing that the Rio Markers were designed to be qualitative tools, rather than a basis for accounting. [6] However, most donor countries reporting to the UNFCCC have adopted this approach. As there is no standardised reporting method, donors interpret the terms ‘significant’ and ‘principal’ in different ways.

Box 1

The Rio Markers

A major source of public climate finance data is that which is reported as ODA to the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC). Relevant spending is tracked using the Rio Markers. Reporters can mark a project as having either a significant or principal climate change adaptation or climate change mitigation policy objective, signalling the extent to which any project is relevant. Projects marked as ‘Principal’ have adaptation or mitigation as the primary objective, whereas projects marked as ‘Significant’ have other objectives and may have been adjusted to incorporate climate concerns. Climate-related ODA varies widely in terms of project focus and relevance.

Countries also apply different coefficients when reporting to the UNFCCC. While they should have the best understanding of the climate relevance of their own programming, their aggregated total estimates are incomparable. For example, if all countries were to follow Australia and Canada and count 30% of the value of significant-marked projects (and 100% of principal-marked projects), then this would yield a bilateral adaptation finance estimate of US$30 billion between 2018 and 2020. Conversely, if all countries followed the Czech Republic, Iceland, Poland and Slovenia, and counted 100% of all projects, the estimate rises to US$67 billion. Furthermore, the coefficients used by each reporting donor are not always immediately apparent. The OECD does perform checks via intermittent surveys, [7] but this information is not immediately clear to those consuming the UNFCCC reported data.

The principal/significant distinction also simplifies and hides a spectrum of relevance and limits the accuracy of reporting. The DAC has made welcome steps towards harmonising Rio-Marker use, but it is not the ultimate custodian of climate finance data. The UNFCCC should clarify which projects count as climate finance and the value of other projects with climate as a secondary concern. It should also require donors to provide documentation so that others can assess projects’ relevance without needing to engage in detective work.

The way forward

Donors reporting to the DAC should agree on a consistent way to use the Rio Markers and an objective grounding to determine what counts as a significant or principal climate focus. Project documentation should be included in data submissions so that others can assess this.

Issue 4: Commitments vs disbursements

The issue: Lack of specificity

The UNFCCC reporting rules currently allow countries to report on either commitments or disbursements. Many providers report one or the other, and some countries report a mix of both. Aside from making it difficult to obtain an aggregate picture – by necessitating the addition of apples and oranges – if there is no disbursement data then it is impossible to hold countries to account when it comes to what actually matters: the amount of climate finance that reaches low- or middle-income countries.

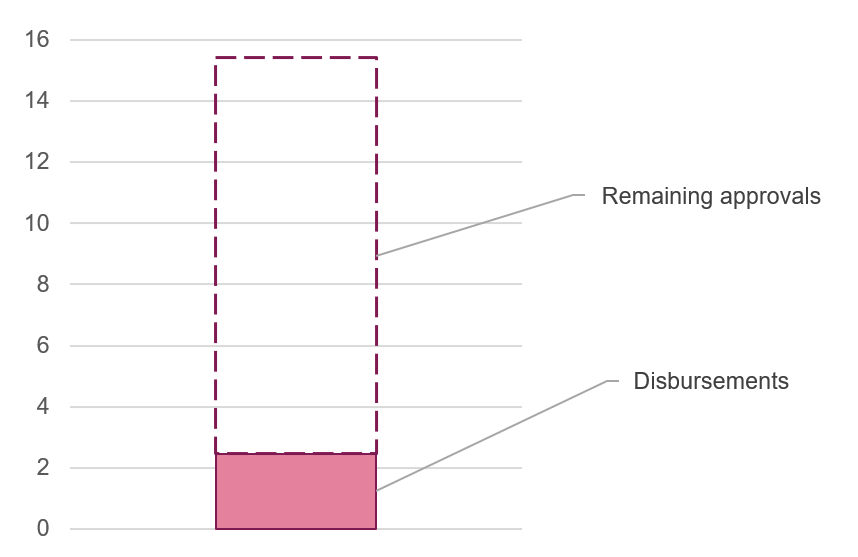

Most data sources [8] show a distinct gap between what is committed, pledged or approved, and what is actually disbursed. This is true for all development finance, but the gap is even larger for climate finance. While 86% of committed funds were disbursed for overall development finance between 2013 and 2017, the figure was only 62% [9] for finance with climate as its principal objective. Accessing climate finance has historically been difficult [10] – in part due to significant bureaucratic hurdles [11] – resulting in many committed funds sitting idle. Given the lack of one-to-one correspondence between commitments and disbursements, it is important to track both to ensure that countries are receiving the help they need in a timely fashion to avert loss, damage and suffering.

Figure 1: There was a significant gap between approvals and disbursements from climate funds in the 2017–2021 period.

Climate fund outflows, US$ billions

Stacked bar chart showing the proportion of approved climate funds in US$ billions that were actually disbursed in the 2017–2021 period.

Source: Climate Funds Update. [12]

The way forward

For the sake of transparency, the UNFCCC should require that both commitments – and the disbursements to date against those commitments – are reported. Proper accounting of climate financing should be based on monies or resources that transferred hands, rather than on committed or pledged funds. This will allow for an accurate picture of provided support. New pledges should also be accompanied by a delivery plan and a timetable of disbursements.

Issue 5: Defining additionality

The issue: Lack of clarity

Despite parties at COP15 agreeing that the US$100 billion climate finance target referred to new and additional finance, there was insufficient attention paid to what this actually meant or how it would be measured. Consequently, different countries have different interpretations. Some of these are unhelpful: several countries define new and additional as ‘newly disbursed funds in the reporting year’, [13] suggesting that all climate finance is new and additional by definition. With no baseline agreed and insufficient detail provided on reporting methodology, it is impossible to assess additionality within the current data systems.

The way forward

This issue needs revisiting at COP27. While there may be crossover between some climate and development objectives (adaptation in particular), the lack of clear identification allows development finance to be redirected away from life-saving programmes. One solution would be to assign projects ODA and climate coefficients. For example, if 40% of a project is counted as climate finance, only 60% should count as ODA. This is similar to the way in which donors report projects with different sectoral objectives in other datasets. At a minimum, it should be possible to identify ODA projects reported to the UNFCCC in other data sources, otherwise it is impossible to tell whether they are genuinely new projects.

Conclusion

Data on international public climate finance lacks transparency, comparability and comprehensiveness. While the US$100 billion goal was not met by its target date in 2020, there is some optimism that it may be met before 2025. However, given the current state of climate finance data, it is impossible to know for sure. Without a better reporting framework, wealthy countries cannot be held accountable for their commitments and donors have little insight into the performance of others. The more malleable the measurements, the more that targets are undermined and cease to have the power to incentivise greater action. Countries can currently meet their pledges using accounting tricks and relabelling. This must change so that urgently required action can be delivered.

As climate finance is pledged, it is important that climate spending is measured robustly and accurately. It is essential to mobilise additional finance and hold countries accountable to their climate finance commitments (while maximising the impact of existing and planned action) to support the most vulnerable populations in building resilience to hazards and risks caused and/or exacerbated by climate change. To ensure future targets are met, we recommend that:

- Climate finance data is comprehensively tracked and measured across all providers in a comparable way.

- Donors provide full details on the instruments used to provide climate finance, including loan terms.

- Donors agree on a consistent approach to using the Rio Markers and an objective grounding for assessing what counts as a significant or principal climate focus. Project documentation should be included in data submissions so that others can assess this.

- Disbursements are reported as well as commitments. The latter are of limited value on their own and there is a known gap between the two.

- Countries revisit the additionality question, even if it is politically difficult. At the very least, a baseline should be established for climate finance provision and climate finance data should be fully linked to aid datasets.

If countries are to combat the worst effects of climate change, it is essential that these recommendations are followed. A complete understanding of the resources that have been delivered and what more is needed to support the most vulnerable communities is the first step in ensuring responsibility and accountability for our global future.

Notes

-

1

Oxfam, 2022. Climate finance short-changed: The real value of the $100 billion commitment in 2019–20. Available at: https://www.oxfamamerica.org/explore/research-publications/climate-finance-short-changed-the-real-value-of-the-100-billion-commitment-in-20192020/ .Return to source text

-

2

Pauw, W.P. et al. ‘Post-2025 climate finance target: how much more and how much better?’, Climate Policy, 2021. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14693062.2022.2114985 .Return to source text

-

3

Weikmans, R. & Timmons Roberts, J. ‘The international climate finance accounting muddle: is there hope on the horizon?’, Climate and Development, 11:2, 2017, pages 97-111. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17565529.2017.1410087 .Return to source text

-

4

UNFCCC Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA), 2021. Common tabular formats for the electronic reporting of the information on financial, technology development and transfer and capacity-building support provided and mobilized, as well as support needed and received, under Articles 9–11 of the Paris Agreement. Informal note by the co-facilitators https://unfccc.int/documents/279099 .Return to source text

-

5

Development Initiatives, 2022. Wealthy countries may be contributing less to global climate finance than we think. Available at: /blog/wealthy-countries-contributing-less-global-climate-finance/?nav=more-about .Return to source text

Related content

Tracking aid and other international development finance in real time

This interactive data tool lets you track commitments and disbursements of aid and other global development finance between January 2018 and April 2023.

Wealthy countries may be contributing less to global climate finance than we think

DI’s Euan Ritchie examines Japan's climate finance reporting, and why it shows that transparency is vital to understanding how much is really being spent

Climate finance to Africa: What we know about ODA

This blog explores how better climate finance to countries experiencing protracted crisis can contribute towards our global future.