Digital civil registration and legal identity systems: A joined-up approach to leave no one behind: Chapter 2

Birth registration coverage for poor and disadvantaged people

DownloadsThere are significant gaps between the progress of those who are most likely to be left behind and everyone else. However, these gaps are often masked by a reliance on global averages. This chapter provides an analysis of disaggregated current and historic survey data, which shows that progress on birth registration coverage for the poorest, least educated and those living in fragile and conflict affected areas has not kept pace with the rest of the population. This has resulted in increasing inequalities, vulnerable populations being left behind and a risk that these populations will be permanently left behind in the future.

This report analyses birth registration related data from the US Agency for International Development (USAID)’s Demographic and Health Surveys [1] and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys. [2] This data has been integrated with data from the World Bank’s PovcalNet [3] in order to make the observations outlined in Chapter 2 (for a more detailed explanation, see Appendix 2 ). While this study goes to question the accuracy and usefulness of survey data to monitor CRVS progress (see Chapter 3 ), the data is the best currently available and does allow for a number of meaningful conclusions to be drawn.

Birth registration and poverty

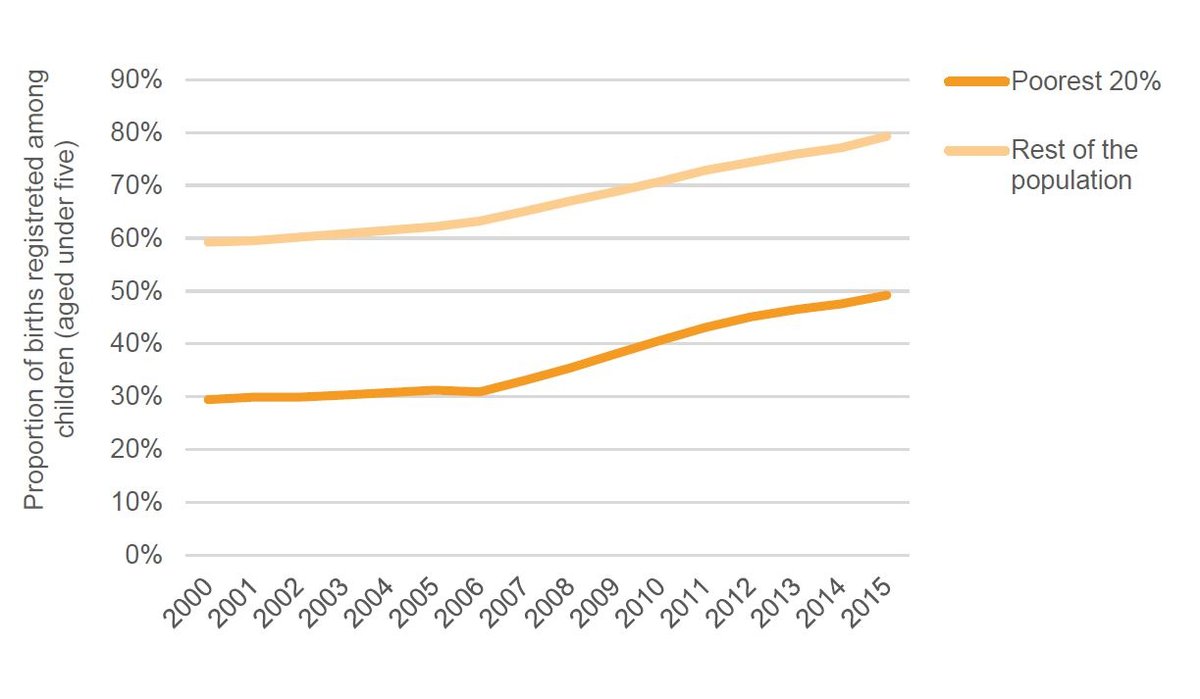

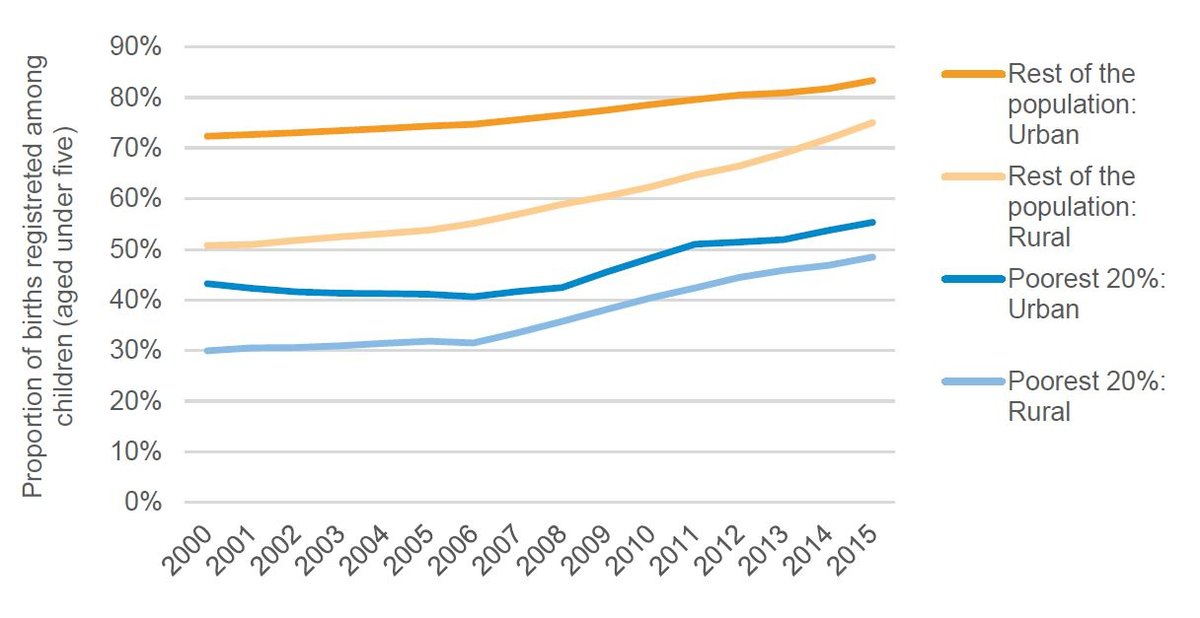

There are persistent gaps in birth registration coverage between those in poverty and the rest of the population. In the years 2000–2015, birth registration coverage for children aged under five living in the poorest 20% of households increased from 29% to 49%. In contrast, registration coverage for children in the rest of the population increased from 58% to 80% (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Proportion of births registered among children (aged under five), 2000–2015

Between 2000 and 2006, birth registration coverage among children (aged under five) for the poorest 20% of the population remained largely constant, at around 30%, before increasing to 49% by 2015. For the rest of the population, birth registration coverage increased from 59% in the year 2000 to 63% in 2006, then increased to 79% by 2015.

Source: Development Initiatives based on World Bank PovcalNet, Demographic Health Surveys and Multiple Indicators Cluster Surveys.

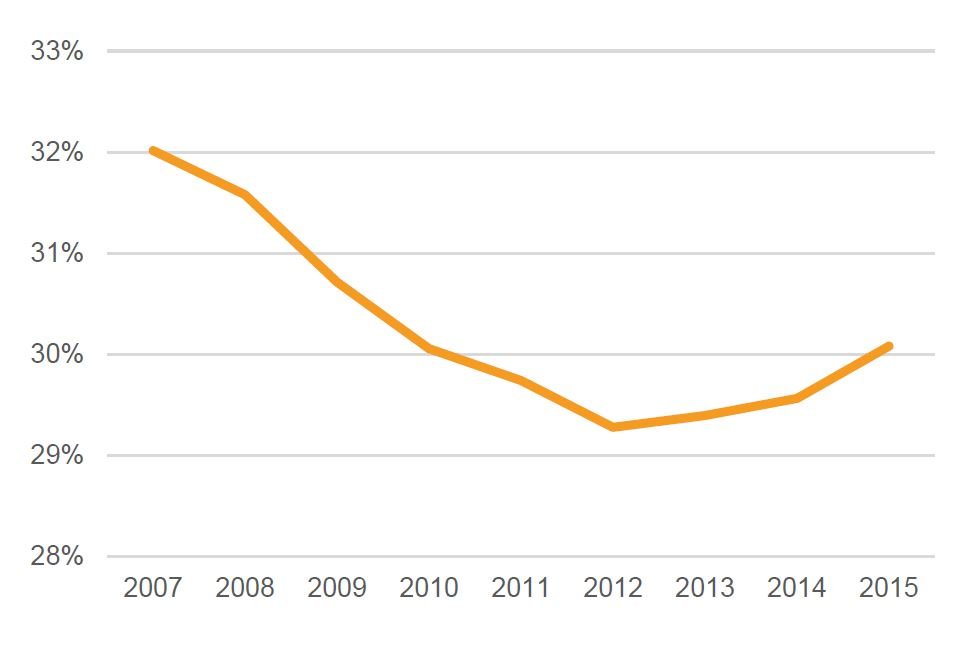

Between 2007 and 2011, the gap between the poorest 20% of households and the rest of the population fell. [4] However, since 2011 the gap has begun to increase again and if trends continue children living in the poorest households will continue to be left behind (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: The gap between the proportion of births registered among children (aged under five) in the poorest 20% and in the rest of the population, 2007–2015

The gap between the proportion of births registered among children (aged under five) in the poorest 20% and in the rest of the population fell from 32% in 2007 to 29% in 2012, before rising again to 30% in 2015.

Source: Development Initiatives based on World Bank PovcalNet, Demographic Health Surveys and Multiple Indicators Cluster Surveys.

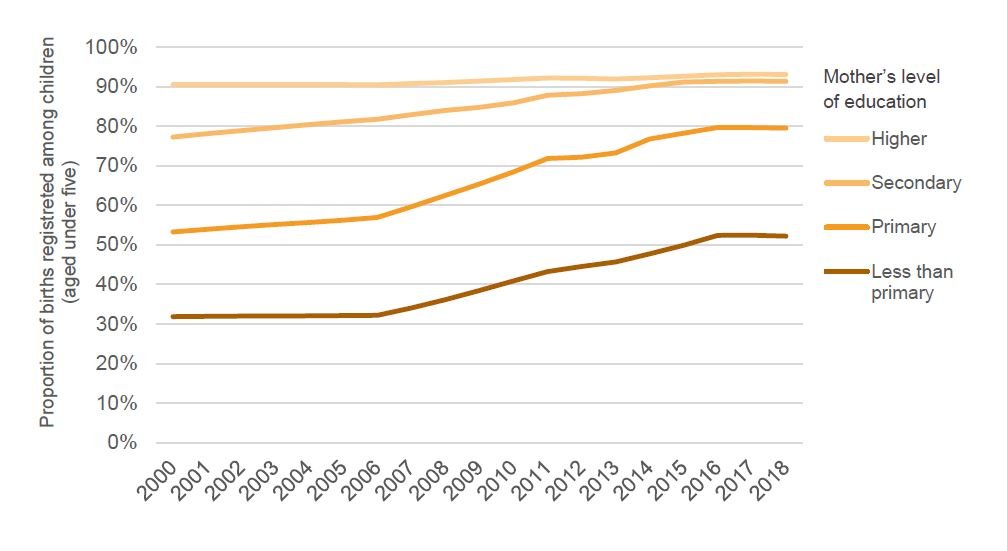

Birth registration and education level

Increasing gaps in birth registration coverage for children are also evident when considering the mother’s level of education. Since 2000, birth registration coverage has improved the most for children with mothers who have a primary level of education, closing the gap between those with higher levels of education. Figure 4 shows that children born to mothers with little or no schooling are being left behind. Almost half of these children remained unregistered during the period surveyed.

Figure 4: Proportion of births registered among children (aged under five) by education level of mother, 2000–2018

Throughout the period, 2000 to 2018, birth registration coverage for children (aged under five) is significantly lower when the mother's level of education is less than primary (compared to all other levels of education), peaking in 2017 at 52%. Birth registration coverage for children (aged under five) is consistently over 90% when the mother has completed higher education.

Source: Development Initiatives based on Demographic Health Surveys and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys.

Similar patterns are seen when the education level of fathers is considered. However, research by Data2x has shown that a child’s registration is more likely to be determined by their mother’s level of education than by that of their father. [5]

Previous research by DI and the Overseas Development Institute found that subnational financing is not well targeted towards the poorest regions, in addition there is little evidence of a progressive allocation of education resources by governments to the regions with the worst education outcomes and no consistent trend among donors. [6]

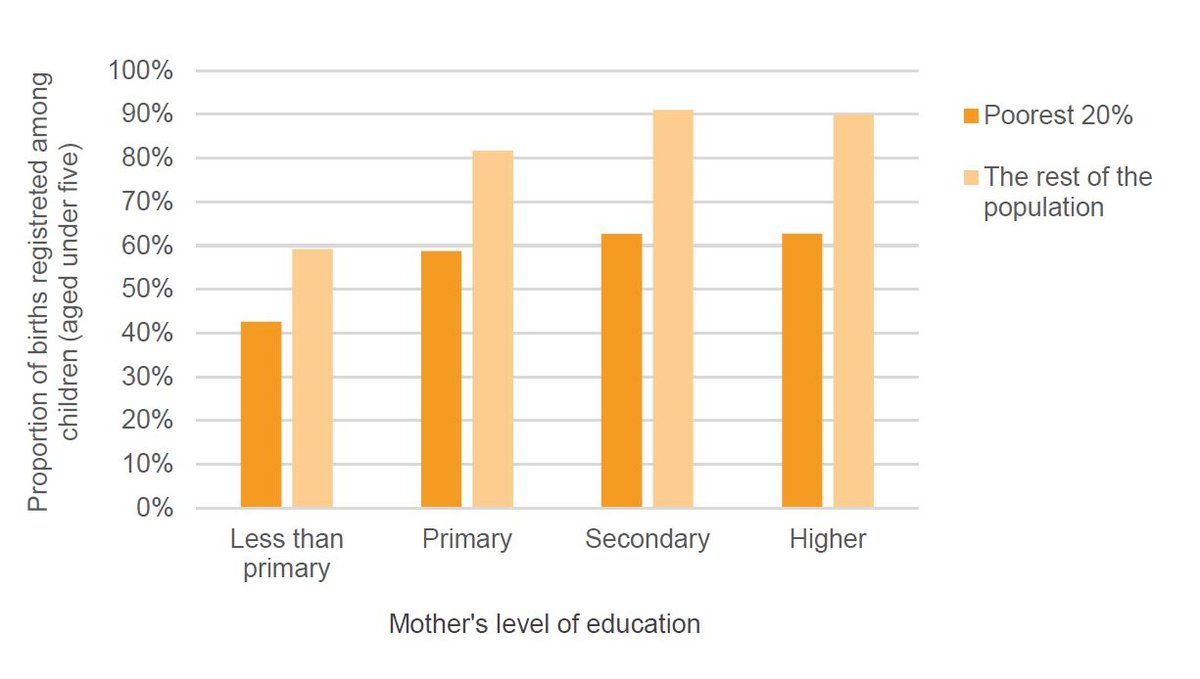

The impact of intersecting factors

The poorest people often face multiple and intersecting deprivations, for example poor nutrition and low levels of education are mutually reinforcing and pass poverty from one generation to the next. For birth registration, inequalities are more extreme when low education and poverty levels intersect. The impact of increasing the education level of the mother is lessened for those living in the poorest 20% of households. Figure 5 shows that the rate of registration for the children of uneducated mothers falls a further 10% (compared to Figure 4) if they are also in one of the poorest 20% of households.

Figure 5: Proportion of births registered among children (aged under five) by poverty and education level of mother, 2015

Regardless of the level of education attained by the mother, birth registration coverage for children (aged under five) is lower in the poorest 20% of the population than in the rest of the population. The greater the level of education the greater this gap is. For mothers in the poorest 20% with higher education, birth registration coverage for children (aged under five) is 63%, compared to 90% for the rest of the population.

Source: Development Initiatives based on World Bank PovcalNet, Demographic Health Surveys and Multiple Indicators Cluster Surveys.

Women and girls may be especially impacted, as previous research has shown that birth registration is negatively correlated with early marriage, young age at birth of the first child and wider adverse health outcomes. [7]

Geographical location can also have an impact on those already left behind by lack of birth registration, poverty and low education levels. Figure 6 illustrates that the poorest people, living in rural areas with lower levels of education face the greatest challenge and are the populations that development programme and domestic services find arguably the hardest to reach.

Figure 6: Proportion of births registered among children (aged under five) by poverty in rural versus urban locations, 2000–2015

Birth registration coverage for children (aged under five) across the whole population, in both rural and urban areas, has increased throughout the 2000 to 2015 period. Birth registration coverage for children (aged under five) has remained lower in the poorest 20% of the population than the rest of the population, in both rural and urban areas. In 2015, birth registration coverage for children (aged under five) in the poorest 20% of the population in urban and rural areas was 55% and 48%, respectively; and 83% and 75%, respectively, for the rest of the population.

Source: Development Initiatives based on World Bank PovcalNet, Demographic Health Surveys and Multiple Indicators Cluster Surveys.

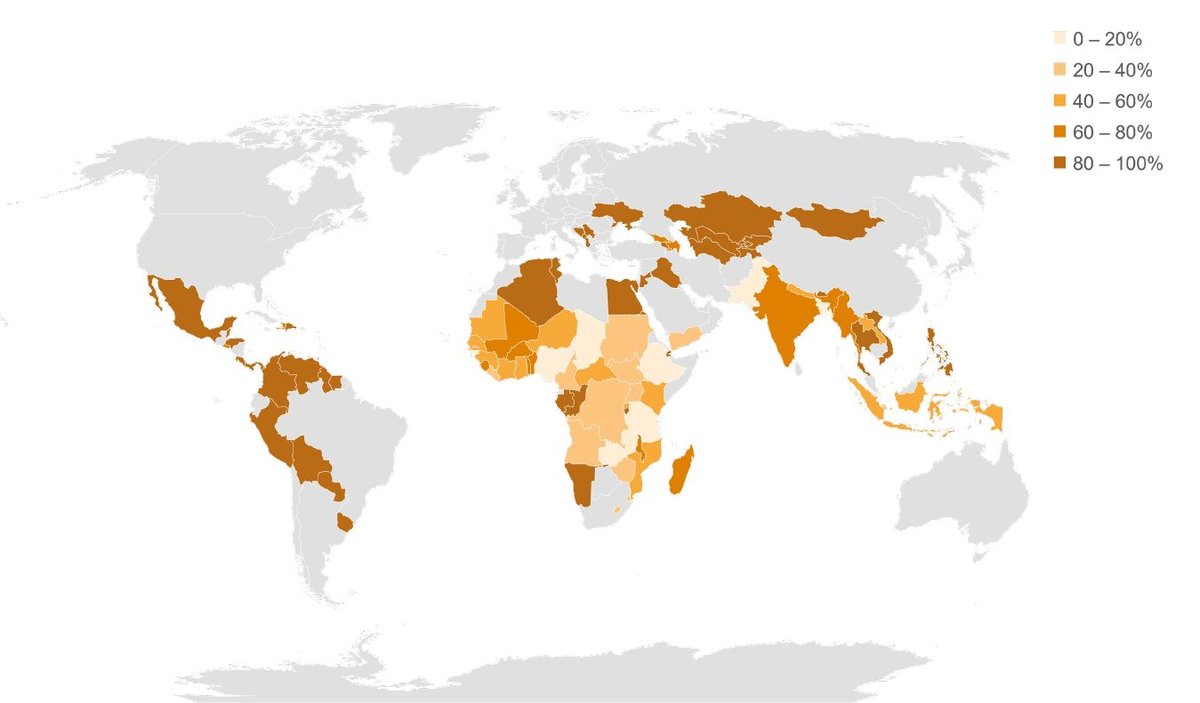

Furthermore, detailed country-level data shows that populations with the lowest levels of birth registration are concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, often in fragile and conflict affected contexts, where extreme poverty persists (see Figure 7). Over 80% of the poorest children aged under five have no birth registration in Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Chad, Zambia, Pakistan, Tanzania, Bangladesh and Nigeria.

Figure 7: Proportion of births registered among children (aged under five) for the poorest 20% of populations across the globe, 2015

World map showing birth registration coverage for children (aged under five), at the national level, for the poorest 20% of populations. Countries where birth registration coverage for children (aged under five) is less than 20% include: Ethiopia, Bangladesh and Nigeria. Countries where birth registration coverage for children (aged under five) is greater than 80% include: Belize, Suriname and Namibia.

Source: Development Initiatives based on World Bank PovcalNet, Demographic Health Surveys and Multiple Indicators Cluster Surveys.

Note: Borders do not necessarily reflect Development Initiatives' position.

Credit: Powered by Bing. © GeoNames, HERE, MSFT, Microsoft, NavInfo, Thinkware Extract, Wikipedia.

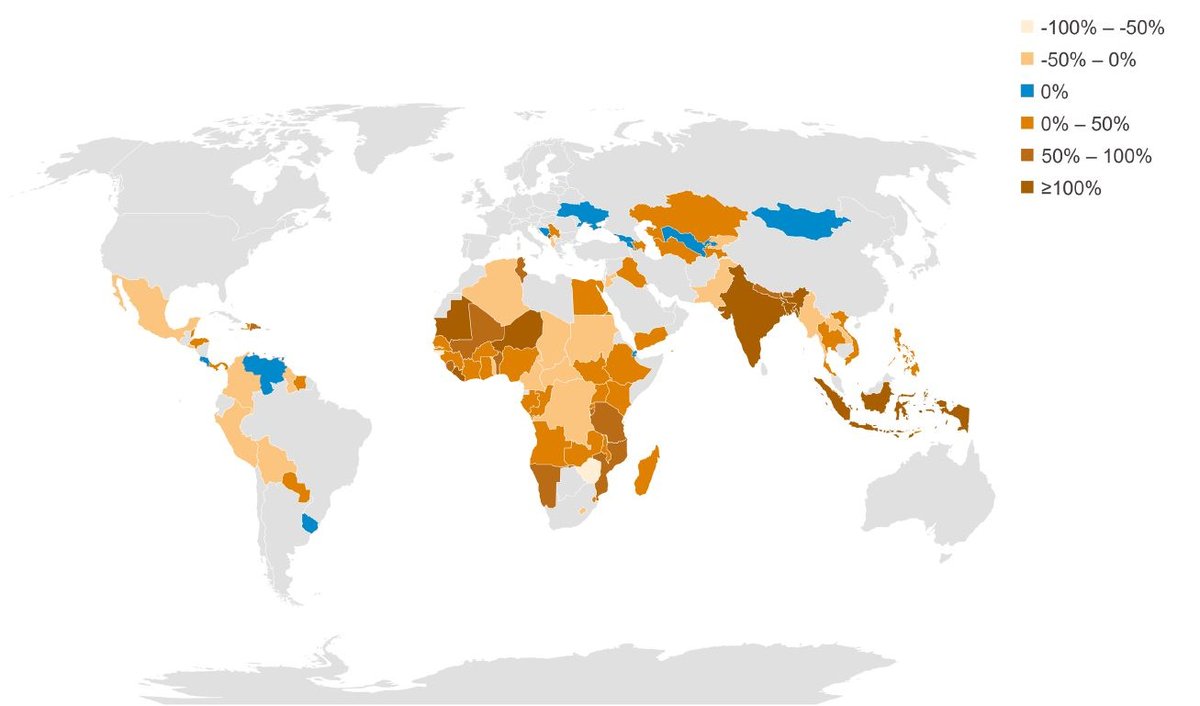

Some countries have made improvements in birth registration coverage for the poorest, however significant conflict and civil unrest has resulted in the proportion of registered births falling below 50% in several central African countries, most notably the Central African Republic, Cameroon and Zimbabwe (see Figure 8). There have also been reported decreases in coverage for the poorest in the Democratic Republic of Congo (from 34% in 2000 to 24% in 2015) and even more starkly in Guinea–Bissau where the impact of conflict, corruption and ongoing instability as seen the birth registration rates for the poorest children drop from 41% in 2000 to only 2% in 2015.

There is a growing recognition that – with a third of people in extreme poverty worldwide living in countries with recurrent crisis [8] – there is a need to build greater coherence across development, humanitarian and peace sectors. [9] Recent analysis from DI looked specifically at how two donors ( Sweden and the UK ) were delivering on this. While there are challenges to integrating approaches there are also clear benefits of joint planning; for example, harmonising approaches between humanitarian, development and peace actors could form the basis of plans to deliver sustainable foundational data systems, such as civil registration, in protracted crisis contexts. [10]

Figure 8: Change in the proportion of births registered among children (aged under five) in the poorest 20% of populations across the globe between 2000–2015* (%)

World map showing change in birth registration coverage, at the national level, for the poorest of 20% of populations. Countries where birth registration coverage for children (aged under five) has fallen by more than 50% are: Guinea-Bissau and Zimbabwe. Countries with over a 100% increase in birth registration coverage for children (aged under five) include: Niger, India and Bangladesh.

Source: Development Initiatives based on World Bank PovcalNet, Demographic Health Surveys and Multiple Indicators Cluster Surveys.

Note: *Nearest available data is used where data for 2000–2015 is not available. Borders do not necessarily reflect Development Initiatives' position.

Credit: Powered by Bing. © GeoNames, HERE, MSFT, Microsoft, NavInfo, Thinkware Extract, Wikipedia.

Downloads

Notes

-

1

The Demographic and Health Surveys Program, https://dhsprogram.com/ (accessed 16 March 2020)Return to source text

-

2

UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys, https://mics.unicef.org/ (accessed 16 March 2020)Return to source text

-

3

World Bank, PovcalNet, http://iresearch.worldbank.org/PovcalNet/povOnDemand.aspx (access 16 March 2020)Return to source text

-

4

The increase in birth registration coverage in India was the main reason for the gap closing.Return to source text

-

5

Data2x, 2018. CRVS and gender. Available at: https://data2x.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/CRVSandGenderBrief.pdfReturn to source text