Disability-inclusive ODA: Aid data on donors, channels, recipients

How much ODA goes to projects focused on the inclusion and empowerment of persons with disabilities? Read analysis of the scale and channels of aid.

DownloadsKey facts

This paper outlines a keyword approach used to identify international aid projects that are targeted for the purpose of disability inclusion, providing an estimate of the overall scale of this aid and an analysis of the key donors, recipients and channels of delivery.

Key findings from this analysis include:

- Aid projects targeting persons with disabilities made up less than 2% of all international aid between 2014 and 2018

-

Aid projects targeting disability inclusion totalled US$3.2 billion between 2014 and 2018, representing less than 0.5% of all international aid.

- Aid to disability-inclusive projects was just under US$1 billion in 2018.

- This was equivalent to less than US$1 per person with disabilities in developing economies.

- Even the five most disability-inclusion-focused donors target just 3% of their aid to this purpose.

- Uptake of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC)’s new ‘disability inclusion and empowerment’ marker is not yet complete, with less than 30% of official development assistance (ODA) in 2018 being assessed against it.

- Using a keyword approach, only 9% of DAC-marked aid was found to be clearly targeted to the purpose of disability inclusion.

- Aid projects that target a mixture of areas make up almost half of all disability-inclusive aid.

- Major recipients of disability-inclusive aid tend to be small island states, but there is little consistency over the past five years.

- Disability-inclusive projects are increasingly overlapping with gender-equality-relevant aid.

- International and donor-based NGOs have channelled the majority of disability-inclusive aid since 2014.

Introduction

Persons with disabilities in development contexts face substantial challenges in terms of achieving self-representation, [1] inclusive employment [2] and integrated education. [3] The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) [4] outlines a framework for the inclusion and self-advocacy of persons with disabilities, while the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) commit to ensure that global development processes are disability inclusive. [5] International aid, known as official development assistance (ODA), provides fundamental support to meeting these goals; measuring the scale of aid that promotes inclusion and empowerment of persons with disabilities is essential to ensuring that persons with disabilities are not left behind.

In December 2019, Development Initiatives (DI) produced a data blog that assessed the historic levels of disability-relevant aid. [6] The work examined records from the OECD DAC Creditor Reporting System (CRS) for projects that contain titles or descriptions that indicate that the purpose was relevant to individuals with disabilities. However, this research did not tackle the issue that not all disability-relevant spending is disability-inclusive. While disability-relevant aid is any and all spending aimed at supporting persons with disabilities, disability-inclusive aid works specifically to accommodate full and equal participation in society. [7]

In February 2020, the OECD DAC released the 2018 compendium of international aid in the CRS. This release contained for the first time a marker for aid projects that are targeted to the ‘inclusion and empowerment for persons with disabilities’. [8] The addition of this marker represents a critical advancement in ensuring better data is available on disability inclusion in development, having long been touted as a much-needed metric; [9] however, donor reporting to this marker is currently voluntary (and incomplete), is not moderated for accuracy or comparability, and is not available for data before 2018. [10]

The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic presents novel and increased challenges to persons with disabilities, making the need for timely and comprehensive reporting of disability-inclusive development assistance all the more important. [11] To complement the OECD DAC disability marker, and until the marker’s coverage grows, this paper examines current and historical aid records to identify projects that are disability inclusive and/or CRPD compliant as a subset of all disability-relevant aid. Using an approach that identifies projects that clearly mention inclusion or inclusive approaches as a purpose, we identified aid that has the clear and explicit goal to promote disability inclusion. [12]

Overview

DI’s keyword methodology identifies international aid projects with policy components explicitly relevant to persons with disabilities by searching project titles and descriptions for applicable words and phrases. It applies multiple sets of keywords and phrases to project records to identify and classify aid projects according to their focus and relevance to disability inclusion. The keyword sets were generated in consultation with disabled persons’ organisations (also known as DPOs, ‘organisations for persons with disabilities’, OPDs) and academic experts in the field (see Appendix).

DI’s approach provides a complementary analysis to that available through the new OECD DAC disability marker. The marker asks donors to indicate whether individual projects are relevant (‘principally’ or ‘significantly’) or not relevant (‘non-targeted’) for the purpose of the inclusion and empowerment of persons with disabilities, in the same way that other project policy markers function (such as gender equality and climate adaptation/mitigation). [13] However, because aid projects may be marked as relevant to multiple focuses, policy markers are voluntarily completed by donors and uptake is not complete (less than 30% of total ODA), it is difficult to ensure comparability in analysis based on the marker alone.

Notably, the method presented herein requires that aid project descriptions be accurate and explicit in their references to targeting persons with disabilities; this means that only projects that clearly aim to improve the livelihoods of persons with disabilities are identified. This approach is purposely narrow and is not intended to substitute or measure the efficacy of the DAC’s disability marker. Rather, it is to provide an appraisal of the scale of targeted disability-inclusive aid where donors have held this purpose as a deliberate and explicit goal.

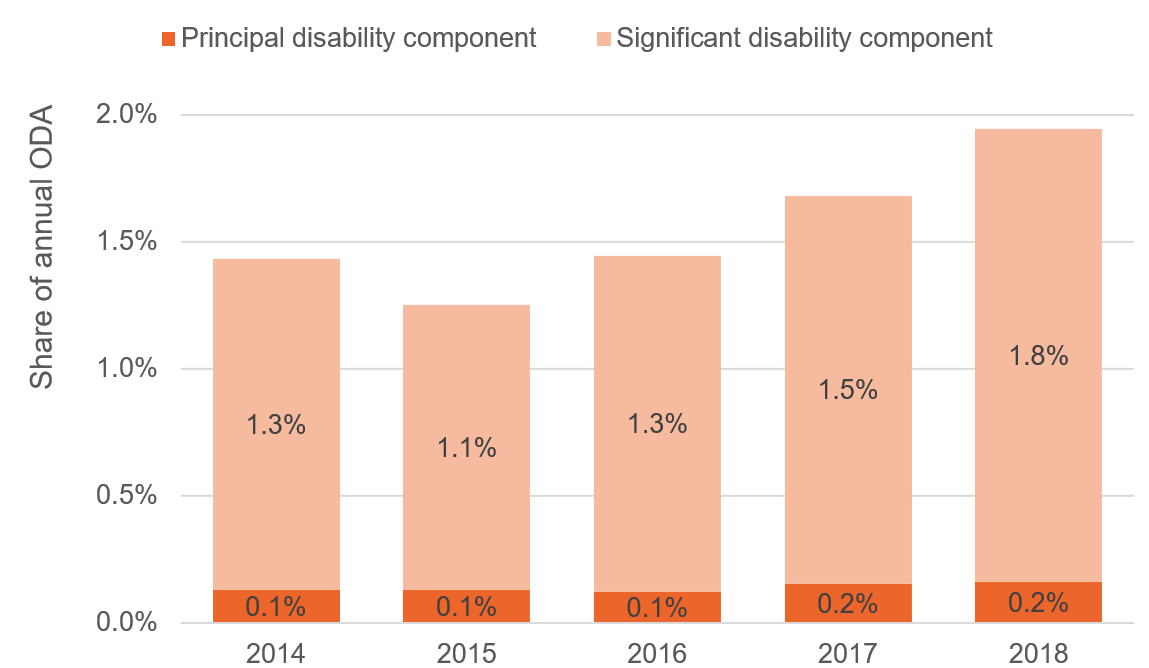

Overall disability-relevant aid

To quantify how much international aid is targeted to disability inclusion, it is necessary to understand the scale of total disability-relevant aid – that is, aid that is targeted to persons with disabilities in any way, whether specifically inclusive or not. Much in the same way as DAC markers, our methodology categorises aid projects according to whether they have a principal or a significant disability component. A project with a principal disability component has the primary purpose of supporting persons with disabilities as a core objective; a project with a significant disability component has a secondary purpose of supporting persons with disabilities as part of a wider objective. [14]

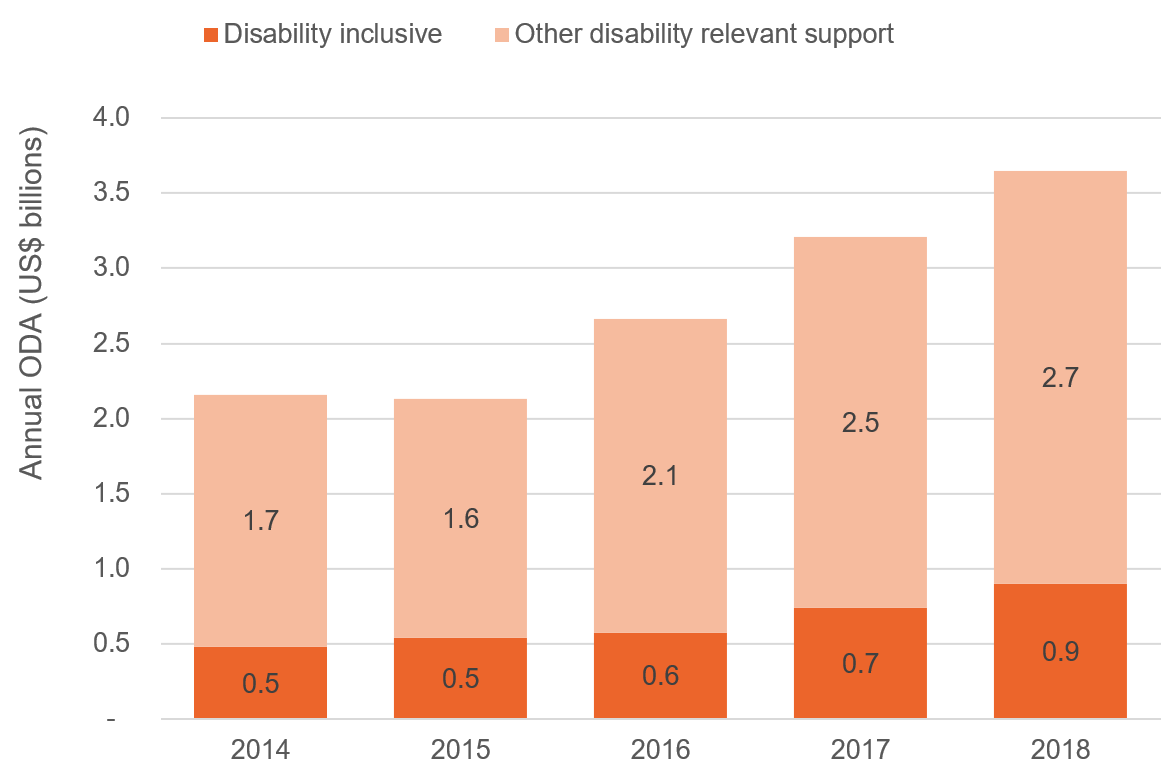

Our analysis finds that between 2014 and 2018 less than 0.2% of all international aid has been allocated to projects that support persons with disabilities as a primary objective. When including projects with a significant objective of assisting or empowering persons with disabilities, spending totalled between 1.3% and 1.9% annually over the period. The total volume of directed disability-relevant aid in 2018 was US$3.6 billion.

Figure 1: Aid projects targeting persons with disabilities made up less than 2% of all international aid between 2014 and 2018

Aid projects targeting persons with disabilities made up less than 2% of all international aid between 2014 and 2018

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD DAC CRS.

Notes: Disability-relevant aid projects were identified using the DI keyword approach.

The share of disability-relevant ODA has increased consistently since 2015, although these increases have occurred mostly due to higher volumes of projects with a ‘significant’ disability component, rather than ‘principal’. In 2018, with the highest share to date, over 90% of identified aid was found in projects that held disability relevance as a secondary or partial purpose; just US$306 million in principally disability-relevant aid was disbursed.

Disability-inclusive aid

Although identified disability-relevant aid projects do work specifically to support persons with disabilities, not all are inclusive or compliant with the CRPD. For example, an aid project that works to create a separate school for children with disabilities, while clearly disability relevant, is contrary to the aim of disability inclusion. Understanding whether disability-relevant aid projects are in fact inclusive and CRPD compliant in their implementation is difficult based on the limited written descriptions available in the CRS. Our approach identified aid disbursements that are clear in their reference to inclusivity and/or CRPD compliance as a goal of the project. Through this, we identified the scale of international aid for which donors have held inclusivity and the CRPD as an integral component.

Since 2014, a total of US$3.2 billion in ODA was identified with disability inclusivity as an integral component, representing an average of 23% of all disability-relevant support over the period. This share has remained generally consistent, although 2018 shows a small increase to 25% of disability-relevant ODA and represents just under US$1 billion in annual aid.

Despite the recent increases in volume, disability-inclusive aid continues to make up only a minor fraction of overall disability-relevant assistance, and a minimal level of overall ODA (less than 0.4%). With less than US$1 billion in aid in 2018, projects focused on the issue of disability inclusion are estimated to be equivalent to less than US$1 per person with disabilities in developing economies. [15]

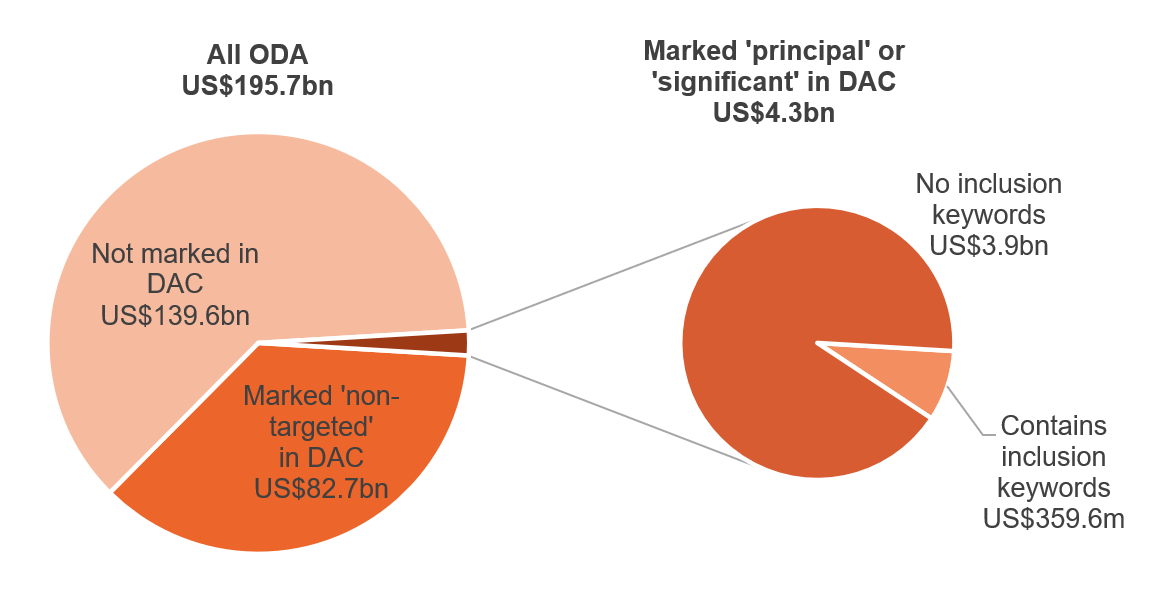

Findings from the DAC marker

The approach of identifying disability-inclusive keywords can be applied to the US$4.3 billion in aid marked by the DAC’s disability marker in 2018. This analysis applies the narrow criteria of explicit and purposeful disability inclusion to the range of projects donors have voluntarily screened against the marker’s criteria and subsequently marked as relevant (‘principal’ or ‘significant’) to the inclusion and empowerment of persons with disabilities.

Although the DAC marker is intended to identify projects that are relevant to the inclusion and empowerment of persons with disabilities, very few DAC-marked aid projects make clear references to disability inclusion or CRPD compliance within project titles or descriptions. Only 9% (US$360 million) of DAC-marked aid in 2018 was clearly described for the purpose of disability-inclusion. However, while this does not mean that the remaining majority of aid under the DAC marker does not promote inclusion and empowerment of persons with disabilities, it does reveal that donors do not consistently make clear disability-inclusivity components in relevant aid projects.

Conversely, a significant remainder of keyword-identified aid is not found to be reported using the DAC marker (US$540 million). However, the marker is not yet universally applied, as only 29% of all ODA was assessed against it. The keyword approach has the benefit of identifying records not assessed by donors, both current and historical.

These findings emphasise the complementary nature of DI’s keyword approach, particularly as a narrow criteria of identification for aid that is disability-inclusive. Findings also reveal the difficulties in uptake and comparability with voluntary donor-marked policy components in aid projects.

Breakdown of disability-inclusive aid by CRPD sub-purpose

The keyword approach allows further classification of disability-inclusive projects according to the alignment of their particular focus with selected articles and themes of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). These areas provide for a greater in-depth analysis of the directed purpose of disability-inclusive aid projects:

- Inclusive employment projects have the purpose of improving employment opportunities and rights for persons with disabilities. An example of such a project would be the creation of an accessible vocational skill training centre for both persons with and without disabilities. These projects align with article 27 of CRPD.

- Inclusive education projects have the purpose of improving inclusivity in education for persons with disabilities. For example, a project that aims to increase integration of persons with disabilities into mainstream schools by improving teacher training on communicating with children with hearing difficulties. These projects align with article 24 of CRPD.

- Family support projects have a focus on empowering and assisting families of persons with disabilities. For example, a project that focuses on income-generating activities for families of persons with disabilities. These projects align with article 23 of CRPD.

- Self-advocacy and rights projects have a primary aim of building the autonomy and self-representation of persons with disabilities. An example project may be the creation and support of self-representative groups for persons with disabilities. These projects align with the overall framework of the CRPD to ensure self-advocacy and rights for all persons with disabilities.

- Mixed purposes focus on a combination of the aforementioned areas; for example, a project that provides both pre-vocation education and vocational training to persons with disabilities within an integrated school.

- Other inclusive/empowerment projects are identified as disability inclusive in purpose but do not clearly align to any of the aforementioned area; an example of this would be a project that contributes to capacity building of disabled persons’ organisations.

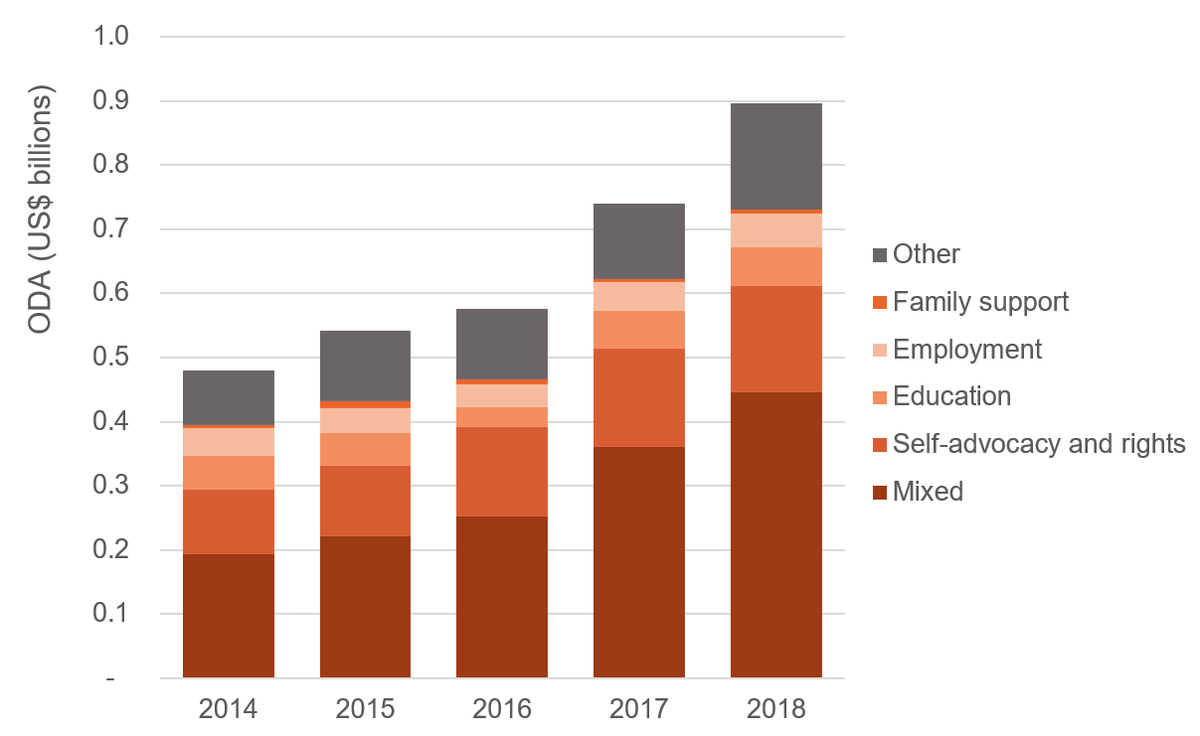

Figure 4: Aid projects that target a mixture of areas make up almost half of all disability-inclusive aid

Aid projects that target a mixture of areas make up almost half of all disability-inclusive aid

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD DAC CRS.

Notes: Disability-inclusive aid projects were identified using the DI keyword approach.

Since 2014, almost half of all disability-inclusive aid projects have been directed to mixed inclusive purposes. Projects in this category were identified to target more than one CRPD sub-purpose, rather than focusing on a single area or theme. Of these projects, 21% of disbursements targeted a mixture of inclusive education and inclusive employment and 61% made up projects that combined improving self-advocacy and rights with other components.

For projects that primarily targeted a single CRPD component, improving self-advocacy and rights of persons with disabilities formed the largest share, representing 21% of all disability-inclusive aid over the period. The second largest share was aid that targeted improving and supporting inclusive education, which totalled 8%. Inclusive employment-focused projects made up 7% of the total, while family support consistently formed the lowest share of dedicated aid, although many projects with mixed CRPD sub-purposes have family support as a partial or secondary objective.

Donors

While the largest donors in terms of disability-inclusive aid (e.g. US, UK) are also those that contribute the greatest sums of total ODA disbursements, understanding which donors are making disability-inclusivity a priority in their aid programmes can be better examined through the share of donors’ total aid that is identified as disability inclusive.

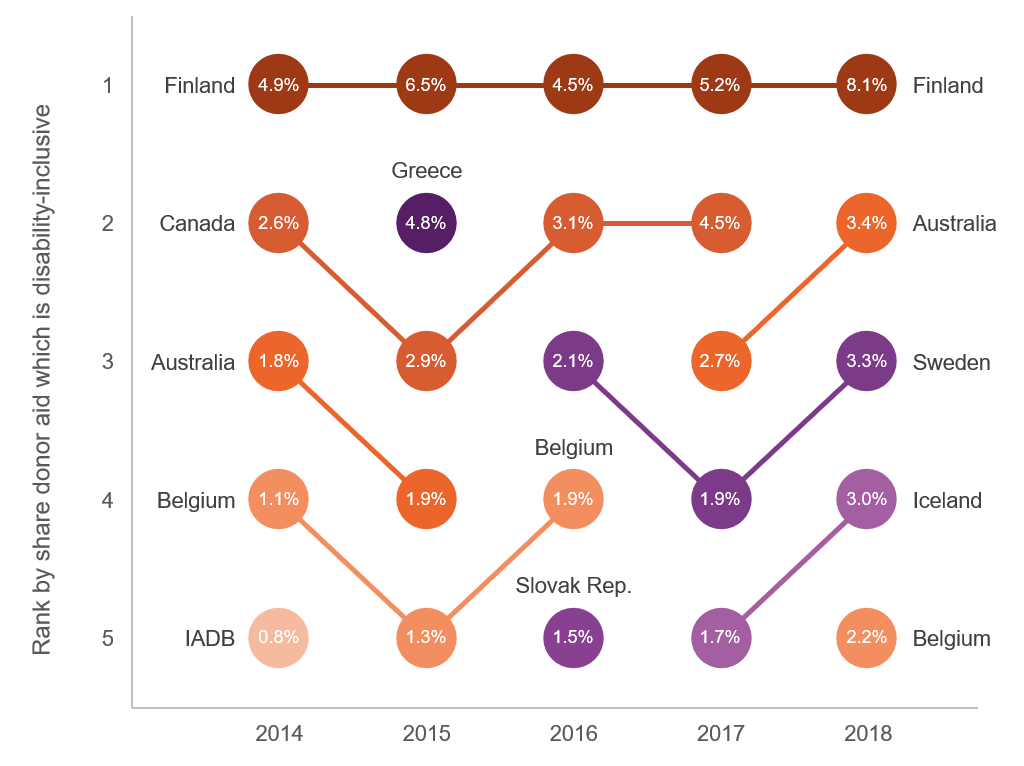

Figure 5: On average, the five most disability-inclusion focused donors contribute just 3% of their total ODA to inclusive projects

On average, the five most disability-inclusion focused donors contribute just 3% of their total ODA to inclusive projects

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD DAC CRS.

Notes: Disability-inclusive aid projects were identified using the DI keyword approach. IADB: Inter-American Development Bank.

Since 2014, Finland has consistently contributed the largest share of its ODA to disability-inclusive aid projects. This share has risen to its highest level in 2018, with 8.1% of Finland’s international aid identified for this purpose. The majority of Finland’s disability-inclusive aid over the period was formed as multi-year programmes, with several projects targeted bilaterally for the purpose of improving and promoting the rights of persons with disabilities, and for inclusive education support (the latter particularly in Nepal).

Canada, Australia, Sweden and Belgium have appeared alongside Finland in the top five in terms of share of disability-inclusive ODA for at least three out of the past five years of data, contributing between 1.1% and 4.5% of their international aid. However, Finland’s sustained relative high levels of disability-inclusive aid represent a benchmark unmatched by other bilateral donors over the last five years.

Recipients

As with donors, understanding which recipients benefit from the highest levels of support to disability-inclusion since 2014 can be analysed through the scale of disability-inclusive projects relative to the total aid received by individual economies. Across the 136 ODA-eligible recipients, the average share of aid projects that are disability-inclusive relative to their total received aid is 0.5%. However, this proportion varies significantly across all recipients: while two economies have seen more than 5% of their aid identified as disability inclusive, 86 economies received less than 0.5% of their aid in disability-inclusive projects.

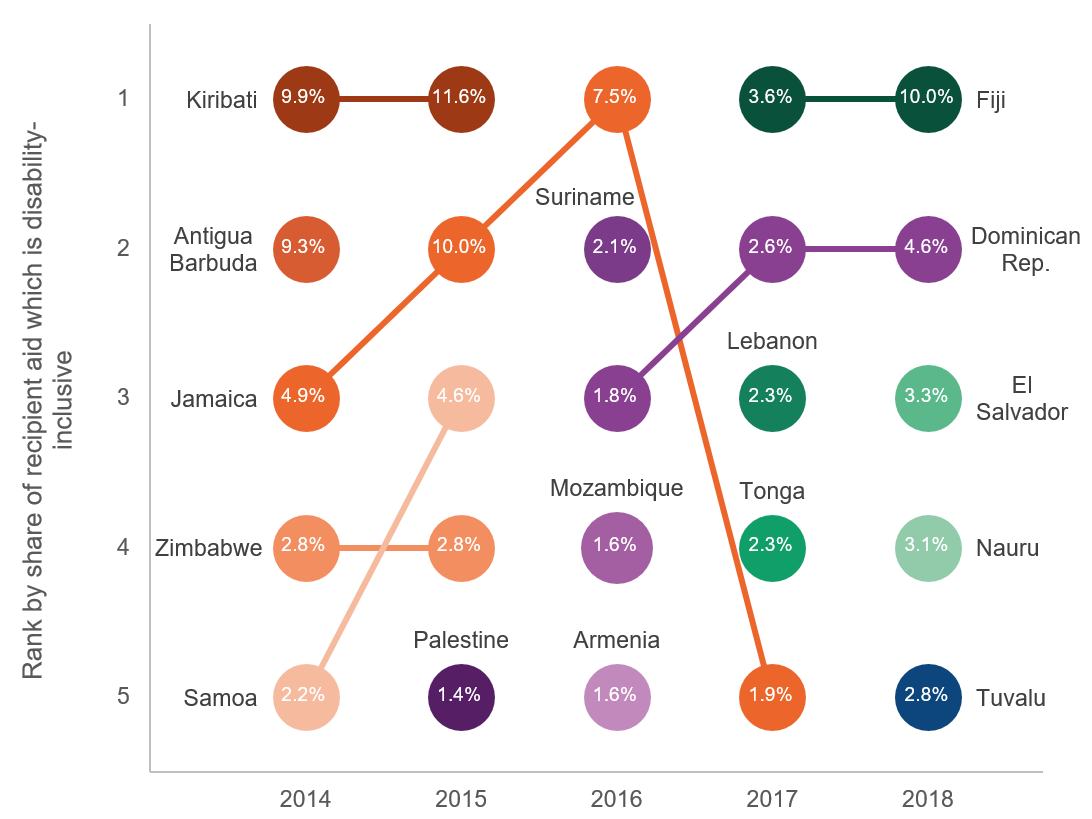

Figure 6: Major recipients of disability-inclusive aid tend to be small island states, but there is little consistency over the past 5 years

Major recipients of disability-inclusive aid tend to be small island states, but there is little consistency over the past 5 years

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD DAC CRS.

Notes: Disability-inclusive aid projects were identified using the DI keyword approach.

There is little consistency across the largest relative recipients of disability-inclusive aid, although island states such as Jamaica, Kiribati, Fiji, Samoa, and Dominican Republic appear several times in the top five in the past five years. The highest recipient share of disability-inclusive aid observed was 11.6% in 2015 by Kiribati; only two other economies (Jamaica and Fiji) have seen 10% or more of their aid targeted to disability inclusion in any given year.

In many cases, disability-inclusion aid projects directed at some of the top recipients (notably Jamaica and Dominican Republic) are purposed with ensuring persons with disabilities are integrated in disaster-relief efforts.

Relevance to gender equality

Article 6 of the CRPD makes clear the link between the issues of gender equality and disability inclusion, recognising that women and girls with disabilities face the potential of double discrimination and are at higher risk of violence and abuse. [16] Gender equality is therefore an integral component of disability-inclusive development. [17]

The scale of aid projects that target these overlapping goals can be measured using the DAC’s gender-equality marker. Like the disability marker, the gender-equality marker allows donors to screen projects for their relevance to the purpose of supporting gender equality. Projects screened against this marker may be determined to have a ‘principal’, ‘significant’, or ‘not targeted’ gender-equality component.

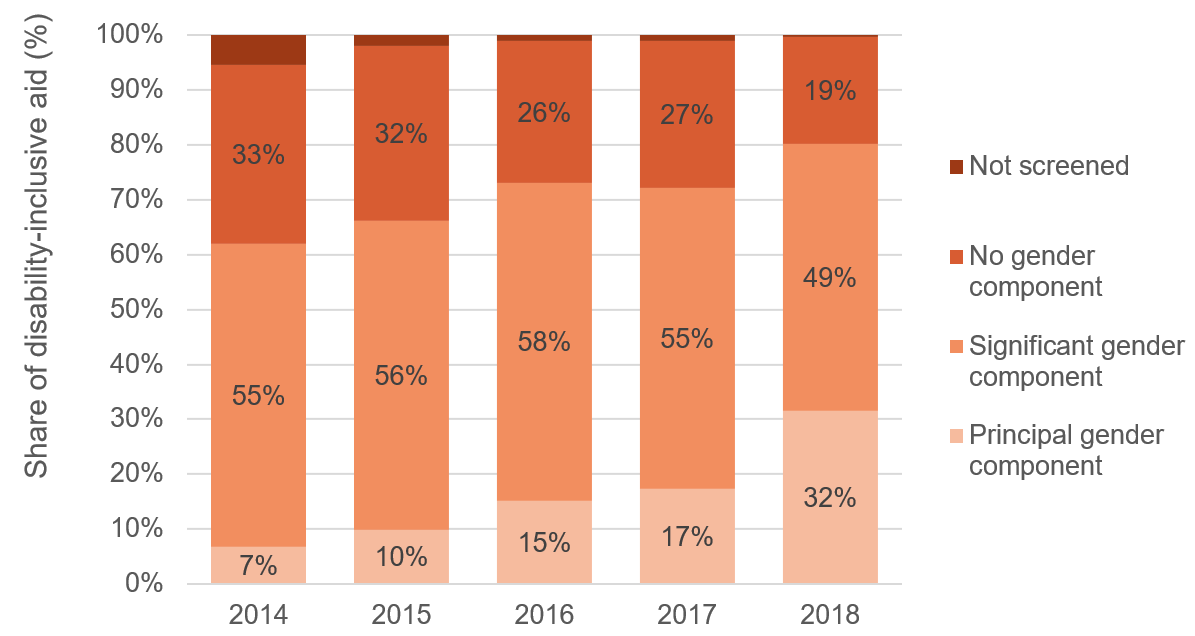

Figure 7: Disability-inclusive projects are increasingly overlapping with gender-equality-relevant aid

Disability-inclusive projects are increasingly overlapping with gender-equality-relevant aid

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD DAC CRS.

Notes: Disability-inclusive aid projects were identified using the DI keyword approach.

On average since 2014, over 70% of disability-inclusive aid has also been marked by donors as either principally or significantly relevant to gender equality. [18] In 2018 the highest overlap to date was reported, with over 80% of disability-inclusive aid also appearing for the purpose of gender equality. Notably, the share of principally marked gender-relevant aid that is also identified for the purpose of disability inclusion has increased strongly over the period, starting at 7% in 2014 and rising to over 30% in 2018.

Channels of delivery

International aid takes many routes to reach its point of delivery. While the majority of ODA is directed through governments, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) form a substantial channel of delivery to enable donor governments to fund effective development projects at the international, national or local level with particular expertise and/or local knowledge.

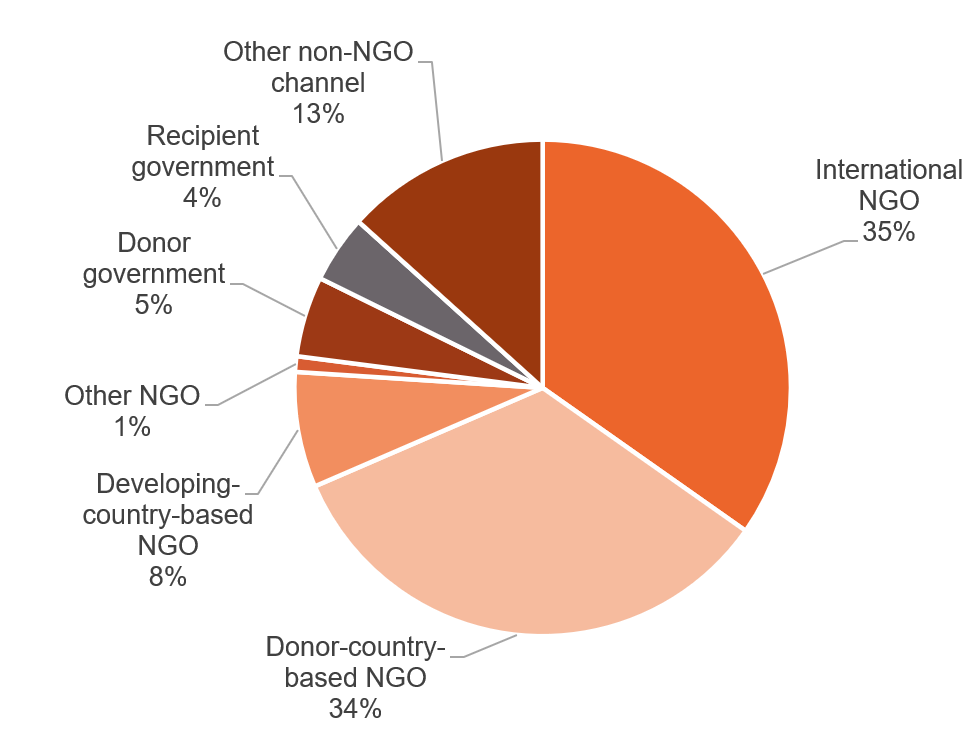

Figure 8: International and donor-based NGOs have channelled the majority of disability-inclusive aid since 2014

International and donor-based NGOs have channelled the majority of disability-inclusive aid since 2014

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD DAC CRS.

Notes: Disability-inclusive aid projects were identified using the DI keyword approach.

Tracking the channels of delivery of aid projects reveals that over three quarters of disability-inclusive aid since 2014 was disbursed and utilised through NGOs. By comparison, NGOs otherwise channelled less than 30% of all aid. NGOs clearly represent a core channel for disability-inclusive aid, and disabled persons’ organisations and other disability-focused organisations have fundamental capabilities in working to support persons with disabilities.

Although the majority of disability-inclusive aid is directed through international and donor-country-based organisations, with a share of 8%, developing-country-based NGOs form a significant channel for these disbursements, whereas these NGOs otherwise make up just 1% of all aid.

Conclusion

The approach within this paper provides an analysis of the scale and paths of targeted disability-inclusive aid projects, finding that such projects make up less than 0.4% of ODA, This is equivalent to less than US$1 per person with disabilities in developing economies in 2018.

The addition of the OECD DAC marker within the CRS for aid projects that are targeted to the ‘inclusion and empowerment for persons with disabilities’ is a positive and crucial step towards creating better data on the issue of disability inclusion in international development. However, complete, consistent, and comparable reporting to the marker is required to ensure its effectiveness.

International aid, when targeted effectively and inclusively, provides fundamental support to empowering and improving the livelihoods of persons with disabilities in developing contexts. Measuring and evaluating this aid through the DAC’s marker, and other complementary analyses, is critical to ensuring that donors are working to meet the goals set out by the SDGs and CRPD.

Appendix

This paper’s methodological approach received valuable contributions and insights from the Center for Inclusive Policy, members of the GLAD Network, members of the International Disability and Development Consortium, Sightsavers Global, Kenya and Nigeria country offices, Polly Meeks (independent consultant specialising in development finance and inclusive development) and Daniel Mont (Senior Research Fellow, University College London and Founding Co-President of the Center for Inclusive Policy).

Methodology

Identifying disability-relevant aid

- Project titles and short descriptions (which can be 150 characters long) of the OECD DAC CRS entries were searched using principal terms to identify projects with ‘principal’ objectives relevant to persons with disabilities (see Table 1 for search terms).

- Long descriptions (which allow more characters to be entered for each project) were then searched for using the same principal terms. Projects captured in the search of long descriptions were marked as ‘significant’ on the assumption that disability assistance or empowerment is one objective of a wider programme.

- A secondary search using significant terms was carried out on the project titles, short descriptions and long descriptions of all projects not already marked as ‘principal’ or ‘significant’. These terms aimed to capture a pool of projects for which disability assistance or empowerment is part of a wider programme.

Correcting for non-targeted aid

- Aid that was identified by the initial relevance keyword search but is in fact not targeted to persons with disabilities was separately identified using false positive search terms. Projects that were flagged using these terms were manually examined to determine whether they represent programmes of which disability relevance is a principal or significant objective, or not an objective at all. False positive search terms were determined based on a manual check of identified records.

- The decision was made that aid projects that target broad health issues (such as HIV/AIDS) without specific reference to persons with disabilities are to be considered non-targeted. This judgment was made based on feedback from disabled persons’ organisations and disability literature. [19]

Identifying disability-inclusive aid

- The titles and short and long descriptions of projects identified as relevant to persons with disabilities were searched with disability-inclusive terms, terminologies and phrasing that clearly reference an explicit inclusion and/or CRPD-compliant purpose. This list of keywords (Table 1) was curated based on consultation with disabled persons’ organisations. Projects that contained these key terms were manually examined.

Identifying sub-purposes

- The titles and short and long descriptions of projects identified as relevant to persons with disabilities were further searched with terms identifying objectives around self-advocacy, inclusive education, inclusive employment and family support (Table 1), and marked accordingly.

- Projects that were marked by more than one of the sub-purposes self-advocacy, inclusive education, inclusive employment or family support are classified as ‘mixed’.

- Projects that were not identified by any of the sub-purpose keywords are classified as ‘other assistance’.

Identifying relevance to gender policy

- The OECD gender-equality policy marker identifies CRS projects that have a principal or significant component objective towards gender equality. [20] Projects that were assigned positive for this marker are considered to be gender-equality relevant.

Channels of delivery: non-governmental organisations

- The CRS identifies aid that is channelled through NGOs. NGOs that channel intellectual disability-relevant aid are categorised based on their geographical presence (donor based, recipient based and international).

Keyword list

All keyword matches are conducted in lowercase. The keyword approach uses a method known as ‘regular expressions’ to match partial and dynamic phrases in the keyword list. For example, the keyword string ‘disab’ will match all instances of the words ‘disability’ and ‘disabled’ . Special symbols are also used in regular expressions, for example, a period ( ‘.’ ) is a wildcard, which will match any single character in its place. Other symbols include the use of braces, which define the length of a wildcard: ‘.{0,1}’ will match any one or zero characters in its place.

Note that the identifying term sets for All disability support include terminologies that may be offensive or not be inclusive; however, as this term set intends to capture as wide a spectrum of disability-relevant aid as possible (including non-inclusive and non-CRPD compliant), it is necessary to include such terms.

Table A1: Search terms used in the keyword methodology

| Group | Terms | |

|---|---|---|

|

All disability support:

principal |

disab, discapaci, incapaci, minusválido, invalidit, infirmité, d-isab, assistive

technology, assistive devices, tecnología de asistencia, la technologie d'assistance, dispositifs d'assistance, dispositivos de ayuda, reasonable accommodation, acomodación razonable, acomodaciones razonables, aménagements raisonnables, accommodement raisonnable, inclusive education, éducation inclusive, educación inclusive, accessibility, accesibilidad, accessibilité, handicap, impairment, impaired, pwd, gwd, cwd, chronic health, chronic ill, maladie chronique, enfermedad crónica, deaf, sordo, sourd, blind, ciego, aveugle, eye health, special needs, necesidades especiales, besoins spéciau, autistic, autism, autist, mental health, santé mentale, salud mental, prosthe, prosthè, prótesi, mobility device, dispositivo de movilidad, dispositif de mobilité, wheelchair, fauteuil roulant, silla de ruedas, plegia, paralys, hearing aid, audífono, dispositif d'écoute pour malentendant, amputation, amputee, amputé, amputa, schizophreni, esquizofrenia, schizophrénie, bipolar, leprosy, sign language, langage des signes, lenguaje de señas, arthriti, artritis, arthrite, rheumat, rhumat, reumat, dementia, démence, demencia, spina , hydrocephalus, hidrocefalia, l'hydrocéphalie, diabetes, diabète, special education, educación especial, éducation spéciale, learning difficult, learning disa, difficultés d'apprentissage, dificultades de aprendizaje, discapacidad de aprendizaje, trouble d'apprentissage, learning problem, trisomy.{0,1}21, trisomie.{0,1}21, trisomía.{0,1}21, down syndrom, syndrome de down, síndrome de down, cerebral, cérébrale, crpd, psycho.{0,1}social disab, fetal alcohol syndrome, developmental delay, pmld, neuro.{0,1}development, neuro.{0,1}diverse, albinism, albino, workplace accommodations, aménagements en milieu de travail, alojamiento en el lugar de trabajo |

|

|

All disability support:

significant |

vulnerable group, vulnerable people, vulnerable population, vulnerable individual,

vulnerable girl, vulnerable women, vulnerable boy, vulnerable men, vulnerable refugee, who are vulnerable, which are vulnerable, vulnerable child, marginali.ed group, marginali.ed people, marginali.ed population, marginali.ed individual, marginali.ed girl, marginali.ed women, marginali.ed boy, marginali.ed men, marginali.ed refugee, who are marginali.ed, which are marginali.ed, marginali.ed child, marginali.ed and young, war victim, victimas de guerra, victimes de guerre, victim. of war, landmine victim, victime de mine, víctima de minas terrestres, landmine survivor, sobreviviente de minas terrestres, survivant d'une mine, inclusive education, éducation inclusive, educación inclusiva, inclusive employment, empleo inclusivo, emploi inclusif |

|

| Inclusivity |

inclus, empower, habiliter, autorizar, rights, droits, derechos, advocacy, plaidoyer,

abogacía, self-representative, auto-représentant, auto-representante, autonomy, autonomie, autonomía, integration, intégration, integración, autogestores, accessiblity, accessibilité, accesibilidad, assistive technology, assistive devices, tecnología de asistencia, la technologie d'assistance, dispositifs d'assistance, dispositivos de ayuda, reasonable accommodation, acomodación razonable, acomodaciones razonables, aménagements raisonnables, accommodement raisonnable, rehabilitation, réhabilitation, rehabilitación, crpd, workplace accommodations, aménagements en milieu de travail, alojamiento en el lugar de trabajo |

|

| Self-advocacy and rights |

empower, habiliter, autorizar, rights, droits, derechos, self.advoca, autogestores,

self.representative, auto.représentant, auto.representante, autonomy, autonomie, autonomía |

|

| Employment |

employ, emplear, empleo, emploi, travail, trabajo, job, labour, labor[.], labor cash

for work, vocation, vocación, profession, profesión, skills, compétences, habilidades, livelihood, moyens de subsistance, sustento, earning, revenus, ganador, microcredit, microcrédit, article.{0,1}27, workshop, atelier, business, affaires, negocio, workplace, social protection, social security, sécurité sociale, protection sociale, protección social, seguridad social, assistive devices, tecnología de asistencia, la technologie d'assistance, dispositifs d'assistance, dispositivos de ayuda, reasonable accommodation, acomodación razonable, acomodaciones razonables, aménagements raisonnables, accommodement raisonnable, workplace accommodations, aménagements en milieu de travail, alojamiento en el lugar de trabajo |

|

| Education |

educat, éducation, educa, éduquer, learning, apprentissage, aprendizaje,

article.{0,1}24, class, classe, clase, school, college, university, escula, colegio, universidad, école, collège, université, teach, enseñar, enseigner |

|

| Family support |

parent, padre, sibling, fratrie, hermano, family, families, famille, familia,

article.{0,1}23 |

Downloads

Notes

-

1

United Nations. Relationship between Development and Human Rights. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/issues/relationship-between-development-and-human-rights.html (accessed 1 July 2020)Return to source text

-

2

GSDRC, 2015. Disability inclusion. Available from: https://gsdrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/DisabilityInclusion.pdfReturn to source text

-

3

International Disability Alliance, 2020. What an inclusive, equitable, equality education means to us. Available from: http://www.internationaldisabilityalliance.org/sites/default/files/ida_ie_flagship_report_2020-as_of_24.06.20.pdfReturn to source text

-

4

United Nations, 2008. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – Articles. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-2.html (accessed 1 July 2020)Return to source text

-

5

Goal 4 (inclusive education), Goal 8 (inclusive employment), Goal 10 (social, economic and political inclusion), and Goal 11 (accessible infrastructure).Return to source text

Related content

Key trends in aid targeting persons with intellectual disabilities

DI’s Dean Breed outlines three key trends in how ODA is targeting persons with intellectual disabilities – considering what this means for recipients and what donors can do to improve the lives of persons with intellectual disabilities.

Generating disability statistics: Models of disability measurement, history of disability statistics and the Washington Group Questions

This background paper examines how data collection on disability has evolved over the last 200 years, as well as the challenges involved in generating disability statistics, and takes a detailed look at the Washington Group Questions.

Data to support disability inclusion

Read more about our work to create and test innovative approaches to improve the long-term economic empowerment and inclusion of persons with disabilities in Kenya and Uganda.