Domestic financial flows in Uganda before and during Covid-19

This briefing tracks domestic revenue and spending to key pro-poor sectors in Uganda before and during the Covid-19 pandemic.

DownloadsExecutive summary

This paper tracks the flow of financial resources in Uganda. It outlines the Government of Uganda (GoU)’s response to Covid-19, resource allocation to key sectors, changes in domestic revenue collection, the implications of the allocations and responses on the government’s expenditure, and public debt. The latest budget estimates for financial year (FY)2021/22 and the approved budgets for the previous FYs are used to track domestic financial resources. Unless stated otherwise, the comparison is made between the two FY periods: before Covid-19 (2017/18 and 2018/19) and during Covid-19 (2019/20 and 2020/21). The implications of the changes in revenue, planning public expenditure and public debt on people living in poverty are highlighted.

Covid-19 continues to negatively impact Uganda’s healthcare systems, its economy, and the livelihoods of its citizens. While the country’s first confirmed case of Covid-19 was reported on 21 March 2020 (weeks after many of its neighbouring countries), Uganda currently faces a brutal second wave of Covid-19 characterised by higher number of infections and deaths amid severe vaccine shortages and overstretched public hospital capacity [1] [2] .

The government’s response to Covid-19 in Uganda has involved harsh and restrictive containment measures, including a three-month total lockdown in the early phase of the outbreak. While there was subsequently a temporary easing of restrictions, this was followed by, at the time of writing, a renewed strict enforcement and a lockdown.

Uganda is currently reporting a relatively higher number of cases and deaths in comparison to the first wave. The relaxed enforcement of preventative guidelines and the entry of more virulent strains of the virus into the country have led to this rise in infection rate.

The total lockdown included shutting down air, road and water travel; a ban on social gatherings; and the restriction of people’s movement through a highly restrictive stay-at-home policy, among other measures. This combined response played a significant role in the containment and control of Covid-19 [3] [4] during the first wave. However, the measures at home and elsewhere that helped to curb the spread and impact of Covid-19 had an unprecedented negative effect on the economy. For example, Uganda lost over US$1 billion due to the impact of Covid-19 on tourism, [5] and lost US$200 million as a result of the decline in remittances in 2020. [6] This is partly due to the near complete halt in economic activity during the lockdown and the slow pace of the global economic recovery from the impact of Covid-19.

Key findings

- There has been minimal change in the trend of Uganda’s budgeting and domestic resource allocation to various sectors to improve targeting of allocations towards the people living in poverty and communities most in need during Covid-19.

- More funding is being allocated to interest payments than service delivery under key pro-poor sectors, leaving big gaps in sector funding.

- The financing gaps for the agriculture and health sectors has collectively been increasing. The social development sector has faced consistent under-financing in the five-year period from 2015/16 to 2019/20.

- Gaps in pro-poor sector funding in 2019 and 2020 undermine the government’s ability to manage the immediate impacts of the pandemic on those living in poverty and address longer-term risks of them falling further into poverty. Under financing also presents a major challenge for the government to achieve its development targets under these sectors.

- Covid-19 has severely affected Uganda’s economy with major shortfalls registered in domestic revenue collection. The government may, in the immediate term, need to depend more on external sources to help meet critical funding gaps in service provision for people living in poverty, while also developing long-term financing solutions grounded in improved domestic resource mobilisation.

- While new borrowing is inevitable, public debt reached 50% of GDP at the end of FY2020/21, beyond which public debt becomes unsustainable.

Uganda’s response to Covid-19

Uganda, which has had over 73,000 cases and over 714 reported deaths at the time of publication, is reported to have managed the first wave of Covid-19 well relative to many of its neighbours. [7] While the start of the vaccination programme in March 2021 brought some hope of curbing the spread of the virus, the pandemic has severely affected Uganda’s economy. The impact of Covid-19 in financial terms for 2020 alone is valued at UGX 6,389 billion, or 4.5% of Uganda’s GDP. [8]

The GoU has deployed a multisectoral response to Covid-19, including the:

- Provision of humanitarian assistance [9]

- Distribution of facemasks nationwide

- Supply of personal protective equipment to health workers

- Creation of national and subnational Covid-19 task forces

- Establishment of national and regional treatment centres to contain Covid-19.

The Treasury’s response to Covid-19

Uganda’s response has involved taking measures to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on the economy as well as supporting the most vulnerable people. The GoU started a food distribution campaign and introduced an economic stimulus package for small and micro enterprises affected by Covid-19. The first major move was the passing of a UGX304 billion (US$82.1 million) supplementary budget in April 2020, followed by the launch of a domestic fundraising platform dubbed the ‘national response fund to Covid-19’ to raise additional funding for the Covid-19 response. The Bank of Uganda also lowered its lending rates, first by 1% from 8% to 7% in June 2020 [10] followed by a 0.5% reduction to 6.5% in June 2021 [11] in order to increase access to credit.

Other response measures in the early phase of Covid-19 included investment in the National Youth Livelihood Fund (YLF) and National Agricultural Advisory Services (NAADS) to create more jobs and keep young people in employment. [12] Some of these relief measures were financed by UGX1.087 trillion from the supplementary budget later approved by parliament in June 2020 to facilitate the Covid-19 response by the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Trade and other government entities. [13]

As illustrated, the GoU’s response to Covid-19 has been costly. The GoU’s resources were strained way beyond what was planned for FY2019/20, and increased budget deficits necessitated additional funding. In 2020 alone, the GoU borrowed from various external sources, including a US$300 million loan from the World Bank, [14] US$491.5 million from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) [15] and US$31.6 million from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) [16] to cover Covid-related revenue shortfalls and government expenditure spikes. However, the implementation modalities and targeting of some of the Covid-19 response measures, like the economic stimulus packages and distribution of humanitarian relief to affected communities, was partially flawed, attracting intense public scrutiny. [17] [18] [19]

National public financial flows

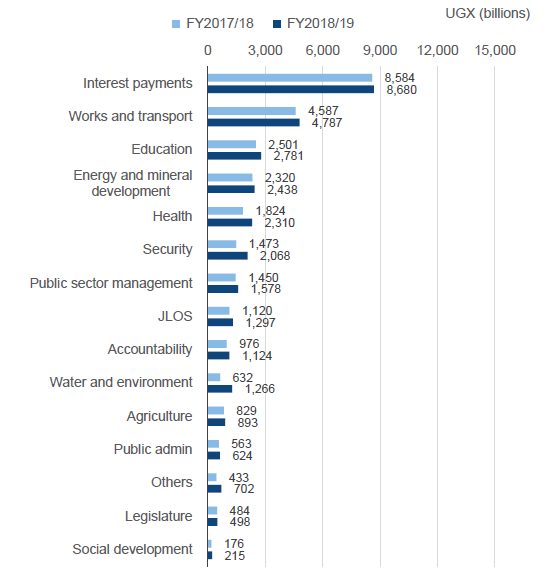

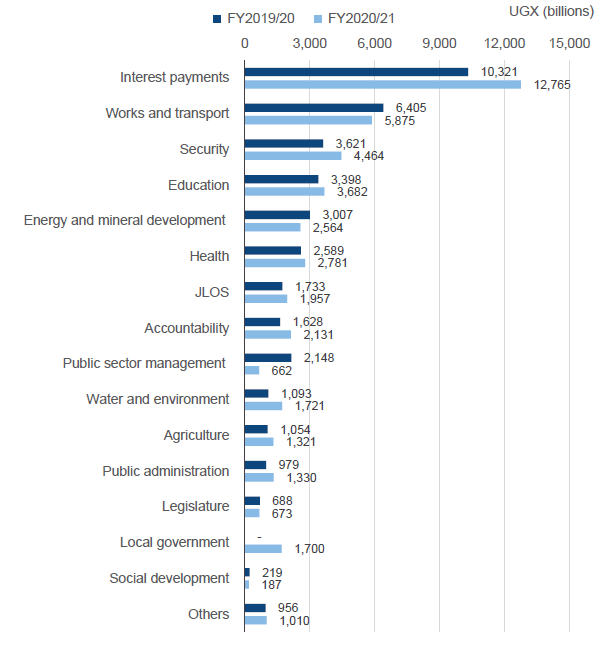

The GoU’s response to Covid-19 resulted in some adjustments in estimated sector budget allocations. Some sectors saw cuts, while others received significant increases. While sectors like health, education, agriculture and water saw modest increases in allocation, there was no major shift in the overall structure or sector prioritisation from FY2019/20 and FY2020/21. Analysis of Uganda’s budget allocation to sectors during Covid-19 shows that interest payments – Uganda’s top financed commitment – remained the most funded area, receiving nearly one third of the budget, followed by allocations to infrastructure, security, education and energy sectors (Figure 1a).

Comparing allocations from FY2017/2018–FY2020/2021 shows that interest payments remained the most financed commitment. The security sector benefited the most: in terms of financing across sectors, it moved from the sixth to the third most financed sector before and during Covid-19. While allocations to education and health increased in nominal terms during this period, education dropped to fourth place while health dropped to sixth place during Covid-19 (Figure 1a).

Figure 1a: Budget allocation before Covid-19

| FY2018/19 | FY2017/18 | |

|---|---|---|

| Social development | 215 | 176 |

| Legislature | 498 | 484 |

| Public administration | 624 | 563 |

| Others | 702 | 433 |

| Agriculture | 893 | 829 |

| Accountability | 1,124 | 976 |

| Water and environment | 1,266 | 632 |

| JLOS | 1,297 | 1,120 |

| Public sector management | 1,578 | 1,450 |

| Security | 2,068 | 1,473 |

| Health | 2,310 | 1,824 |

| Energy and mineral development | 2,438 | 2,320 |

| Education | 2,781 | 2,501 |

| Works and transport | 4,787 | 4,587 |

| Interest payments | 8,680 | 8,584 |

Source: The Ministry of Finance, approved budget estimate for FY2020/21.

Notes: JLOS = Justice law and order sector. A shift from sector focus to program-based budgeting in-line with the new NDP III no longer permits accurate compilation of sector budget allocations based on available budget data for FY2021/22. Data for FY2020/21 is from the budget estimates document.

Local governments (LGs) – Uganda’s focal point of service delivery – benefited significantly from increased budget allocation in FY2020/21 (Figure 1b). The allocation seems to be in response to demands for increased local government funding as a share of the national budget [20] and not necessarily due to Covid-19. A very small share of LG budgets is allocated to service delivery and development. [21]

Figure 1b: Budget allocation during Covid-19

| FY2020/21 | FY2019/20 | |

|---|---|---|

| Social development | 187 | 219 |

| Public sector management | 662 | 2,148 |

| Legislature | 673 | 688 |

| Others | 1,010 | 956 |

| Agriculture | 1,321 | 1,054 |

| Public administration | 1,330 | 979 |

| Local government | 1,700 | - |

| Water and environment | 1,721 | 1,093 |

| JLOS | 1,957 | 1,733 |

| Accountability | 2,131 | 1,628 |

| Energy and mineral development | 2,564 | 3,007 |

| Health | 2,781 | 2,589 |

| Education | 3,682 | 3,398 |

| Security | 4,464 | 3,621 |

| Works and transport | 5,875 | 6,405 |

| Interest payments | 12,765 | 10,321 |

Source: The Ministry of Finance, approved budget estimate for FY2020/21.

Notes: JLOS = Justice law and order sector. A shift from sector focus to program-based budgeting in-line with the new NDP III no longer permits accurate compilation of sector budget allocations based on available budget data for FY2021/22. Data for FY2020/21 is from the budget estimates document.

The security sector also benefited quite significantly from an increase in its budget in FY2020/2021. This increase could be linked to the involvement of the army, police and other security apparatuses in enforcing Covid-19 guidelines, particularly during the recent general elections. The increase in planned allocation to sectors that are not pro-poor, while pro-poor funding gaps have been increasing, is worrisome – especially amid Covid-19.

Trends in pro-poor sector financing in relation to requirements

Infrastructure under the works and the transport sector has been consistently the most funded sector over the past decade. However, the Third National Development Plan (NDP III) now highlights the need to re-prioritise government investment by balancing social and infrastructure spending in order to achieve better development outcomes.

The following section assesses trends in allocation to social sectors (agriculture, health, social development and education) before Covid-19 and during Covid-19. Data on sector funding requirements for the period from FY2017/18 to FY2019/20 is based on the GoU’s planning estimates for the implementation of the Second National Development Plan (NDP II); they are not necessarily on actual sector funding requirements for the same period.

Allocation change to pro-poor sectors before and during Covid-19

The pro-poor sectors [22] discussed in this section are:

- Education

- Health

- Water and environment

- Agriculture

- Social development.

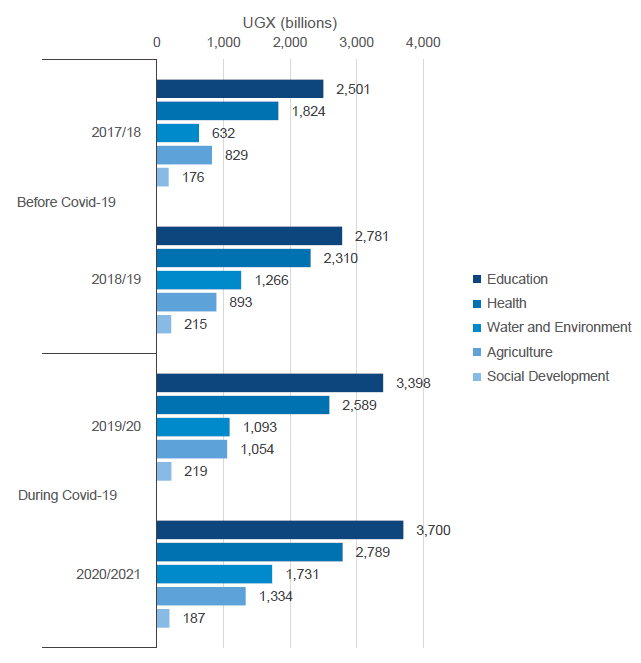

These sectors are all relevant to Covid-19 response. A comparison of sectoral allocation before and during Covid-19 reveals that these sectors – with the exception of social protection – were allocated higher budget funding in FY2020/21 and FY2019/20 compared to FY2018/19 and FY2017/18 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Sector budget allocation before and during Covid-19

A chart showing that the education sector received the highest allocations consistently before and during Covid-19, with the social development sector consistently receiving the lowest.

Source: Development Initiatives, based on data from the Ministry of Finance.

While all sectors except for social development had an increase in budget allocation during Covid-19, these increases have not kept pace with rising needs. This has led to a widening funding gap (see below for a sector-by-sector analysis of this gap).

There has not been a planned rise in sector allocations during Covid-19. The slight increases in planned allocations are typical year-on-year increases rather than the result of a deliberate measure to protect pro-poor sectors from the impacts of Covid-19.

Education

While the level of access to and utilisation of education services has rapidly increased due to the GoU’s investment in the sector and the roll-out of universal primary and secondary education, the quality of public education services in Uganda remains low. Levels of literacy and numeracy are low, and the school dropout rate is high. [23] Moreover, Uganda’s new framework for development emphasises the need of a skilled, innovative labour force as a prerequisite for industrialisation and sustained rapid growth. [24]

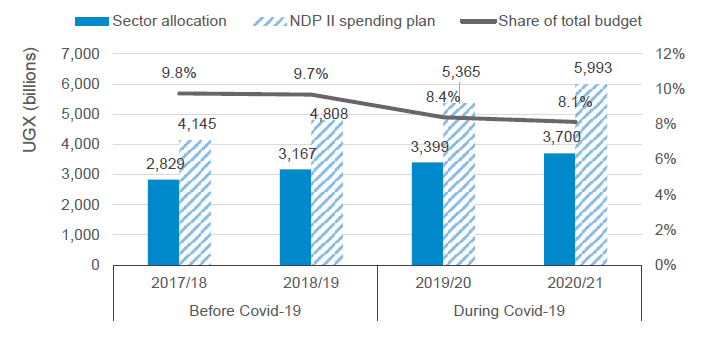

Budget allocation to the education sector has gradually increased from FY2017/18 to FY2020/21; however, the declines in the share of the national budget to the sector over the same period is notable. This decline is even higher during Covid-19 compared to the two FYs before Covid-19.

The gap between the sector development funding plans and allocations during Covid-19 is significant: in FY2019/20 the education sector was allocated 63% (UGX 3,399 billion) of its UGX 5,365 requirement (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Declining share of allocation to education against increasing sector funding requirements

Investment in Uganda’s education is necessary for the country to achieve its development aspirations. While the impact of Covid-19 has limited the available resources available across sectors, it would be detrimental for the funding gap to further increase.

Agriculture

Rapid industrialisation based on increased productivity and production in agriculture form the basis of Uganda’s growth and development strategy in the NDP III. [25] Poverty in Uganda is concentrated in regions in which the majority of households rely on agriculture as a source of income. To address this, the government hopes to re-prioritise investments targeting productive sectors like agriculture.

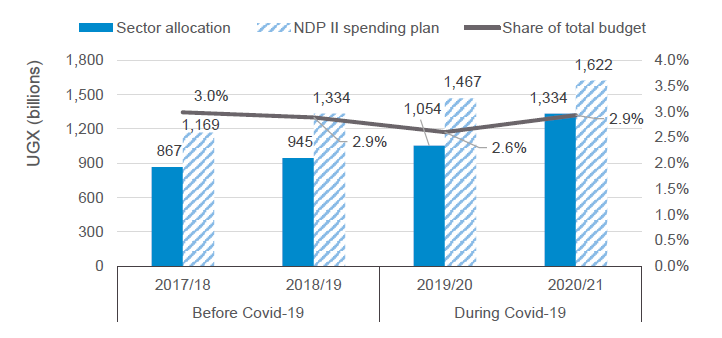

The share of budget allocations to agriculture in the national budget declined over the period from FY2016/17. While allocation to the sector has increased in nominal terms, it represents a declining share of the national budget in the five-year period. Growth in sector funding requirements have outpaced allocations, meaning the gap between sector funding requirements is widening. For instance, in FY2019/20, the sector was allocated just 37% (UGX1,504 billions) of its planned funding requirements of UGX4,049 billion (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Allocation to agriculture sector compared with funding requirements

Investment in Uganda’s agriculture sector has a significant impact on Uganda’s economy because it relies heavily on agriculture, and the sector is important for poverty reduction, as highlighted in Uganda’s Vision 2040. [26] The increasing gap in agriculture financing is therefore likely to undermine the sector’s role as a major contributor to economic growth and development.

Health

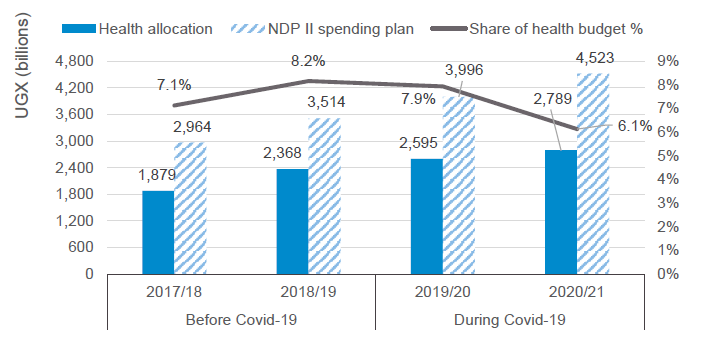

The health sector budget has increased by nearly 100% over the five years, from UGX 1.3 billion in FY2015/16 to UGX 2.6 billion allocated in FY2019/20. [27] Even with another increased allocation in FY2020/21, the health sector budget as a percentage of the total government budget declined from FY2019/20 to FY2020/21 as Covid-19 unfolded. In FY2019/20, health was allocated 64% (UGX 2,595 billion) of the required UGX 3,996 billion. A projection of the funding requirement for the health sector in FY2020/21 shows an even high gap in funding during Covid-19 (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Growing health sector budget funding gap even with increasing sector allocation

Chart showing growing health sector budget funding gap even with increasing sector allocation.

| Before Covid-19 | During Covid-19 | |

|---|---|---|

| 2017/18 | 2018/19 | |

| Health allocation | 1,879 | 2,368 |

| Share of health budget % | 7.1% | 8.2% |

| NDP II spending plan | 2,964 | 3,514 |

Source: Development Initiatives, based on data from the Ministry of Finance and NDP II.

While allocation to the health sector increased by 12% in FY2019/20 and by 7% in FY2020/21, there is no sudden rise in planned allocation to the sector despite its significant requirements during Covid-19.

The source of funding growth in the health budget has been mainly driven by increased external resources from development partners. High reliance on external financial support for the health sector is unsustainable, particularly at a time when key donors are reducing aid to Uganda in part due to the impact of Covid-19 on their economies.

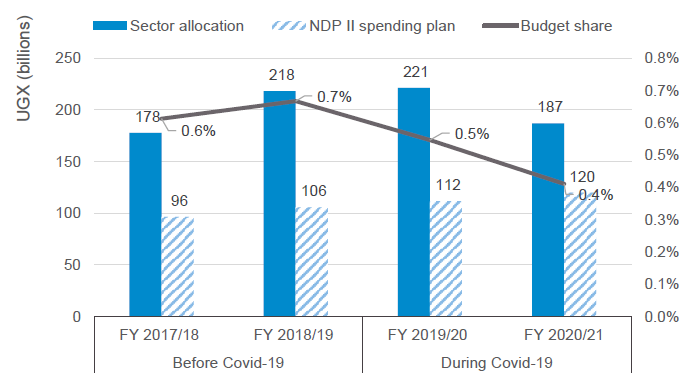

Social development

The social development sector, which includes Uganda’s social protection for vulnerable groups, has been among the least funded sectors in the country. The government has also maintained a low and flat funding plan of 0.8% of GDP throughout the NDP II implementation period. It is therefore not surprising that even the little extra allocation to the sector above the planned funding appears as a positive gap. Budget allocation to the sector has stagnated at 1% of the total budget, while sector allocation has increased by an average of 0.03% of the overall government budget in the five-year period of FY2015/16–FY2019/20. During Covid-19, when vulnerable groups are likely to be disproportionately affected by response measures and the pandemic’s social, economic and health impacts, planned allocation to the sector allocation declined by 15% in FY2020/21 (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Declining share of budget allocation to social development sector budget

The decline in social sector allocation during Covid-19 is unexpected. It goes against the expectation of increased allocation that would have enabled people living in poverty and vulnerable communities who benefit from social protection programmes to weather the impacts of Covid-19 on their livelihoods.

Moreover, sector funding challenges highlighted in the auditor general’s reports before Covid-19 was already affecting the implementation of sector policies and programmes, resulting in the partial and unsustainable fulfilment of the planned targets. [28] [29]

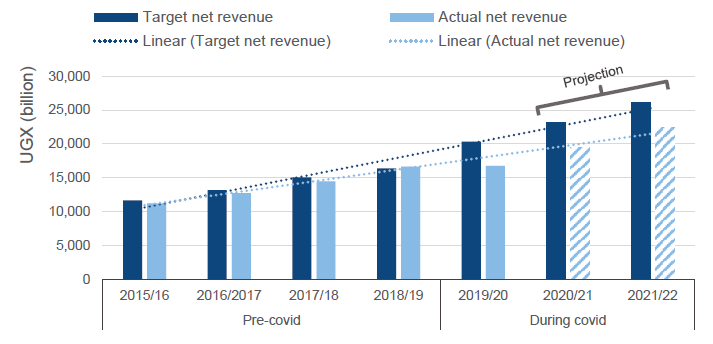

Domestic revenue

Uganda’s domestic revenue collection has grown in the past five years, from UGX 11,231 billion in FY2015/16 to UGX 16,752 billion in FY2019/20. However, the year-on-year growth in net [30] revenue, which is UGX 134 billion, from FY2018/19 to FY2019/20 was the lowest at 0.18% compared to the five-year average of 11.65%. The period during Covid-19 saw a significant shortfall in tax revenue for FY2019/20, UGX 3,592 billion (18%) less than the government’s target for the same year. This was not the case before Covid-19, in fact a surplus revenue was collected in FY2018/19 before the pandemic (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Uganda’s revenue performance before and during Covid-19

Chart showing Uganda’s revenue performance before and during Covid-19.

|

Before

Covid-19 |

During

Covid-19 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| URA (Ugx Bn) | 2015/16 | 2016/2017 | 2017/18 | 2018/19 | 2019/20 |

|

Target

net revenue |

11,635 | 13,177 | 15,062 | 16,359 | 20,344 |

|

Actual

net revenue |

11,231 | 12,720 | 14,456 | 16,618 | 16,752 |

Source: Development Initiatives, based on data from Uganda Revenue Authority, Annual Performance Report FY2019/20.

The revenue collection shortfall of UGX3,952 billion in FY2019/20 presents a major challenge for the government’s development and service delivery plans, which are pegged on increasing capacity for domestic revenue collection.

Gaps in revenue collection associated with Covid-19 mean that the GoU will have to look more at external sources to meet the required funding in the short-term response to Covid-19, service delivery and development financing.

Moreover, shortfalls in tax revenues may translate directly into increased borrowing, and risk of increased debt distress.

The major implication of additional borrowing during Covid-19 has been the unprecedented increase in Uganda’s public debt and resource allocation to debt servicing (see the ' Public debt ' and ' Debt servicing ' sections below).

Government revenue and expenditure projections

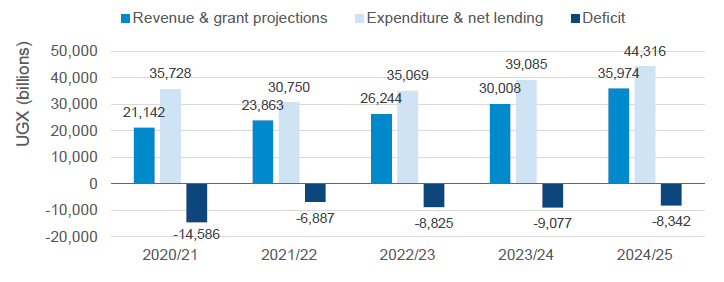

During Covid-19, a key driver of increasing expenditure [31] has been the government’s need to support economic recovery through the provision of economic stimulus packages to various sectors while maintaining significant spending on infrastructure. However, government’s projection of revenues over the next four years presents a positive outlook with the almost year-on-year declining deficits from FY2020/21 to FY2024/25.

Uganda’s estimated expenditures and net lending for FY2021/22 is UGX30.8 trillion (representing a 14% decrease from FY2020/21) against total domestic tax revenue and grants that is projected at only UGX 21.1 trillion. This leaves Uganda with a deficit of UGX 6.9 trillion for FY2021/22, less than half the deficit for FY2020/21 (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Government revenue and budget projections during Covid-19

| 2020/21 | 2021/22 | 2022/23 | 2023/24 | 2024/25 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Revenue

& grant projections |

21,142 | 23,863 | 26,244 | 30,008 | 35,974 |

|

Expenditure

& net lending |

35,728 | 30,750 | 35,069 | 39,085 | 44,316 |

| Deficit | -14,586 | -6,887 | -8,825 | -9,077 | -8,342 |

Source: Development Initiatives, based on data from the Ministry of Finance, draft budget estimates FY2021/22.

The majority (73%) of the deficit for FY2020/21 is expected to be funded through external borrowing. Government spending for FY2020/21 is budgeted at UGX 36 trillion (79% of total budget), of which 11.2% will go to interest payment.

There are gaps between projected government expenditure and revenue for the next four FYs, which shows an inability to meet needs considering the economic impact of Covid-19 and ambitious spending on governance and security and infrastructure sectors that continue to drive government’s expenditure.

In the medium-to-long term, the budget deficit should be narrowed by improved productivity and expanded sources of revenue that set the country on a path of accelerated economic growth. In the short term, the wide gap in financing will require increased borrowing, which will plunge the country into a bigger public debt burden.

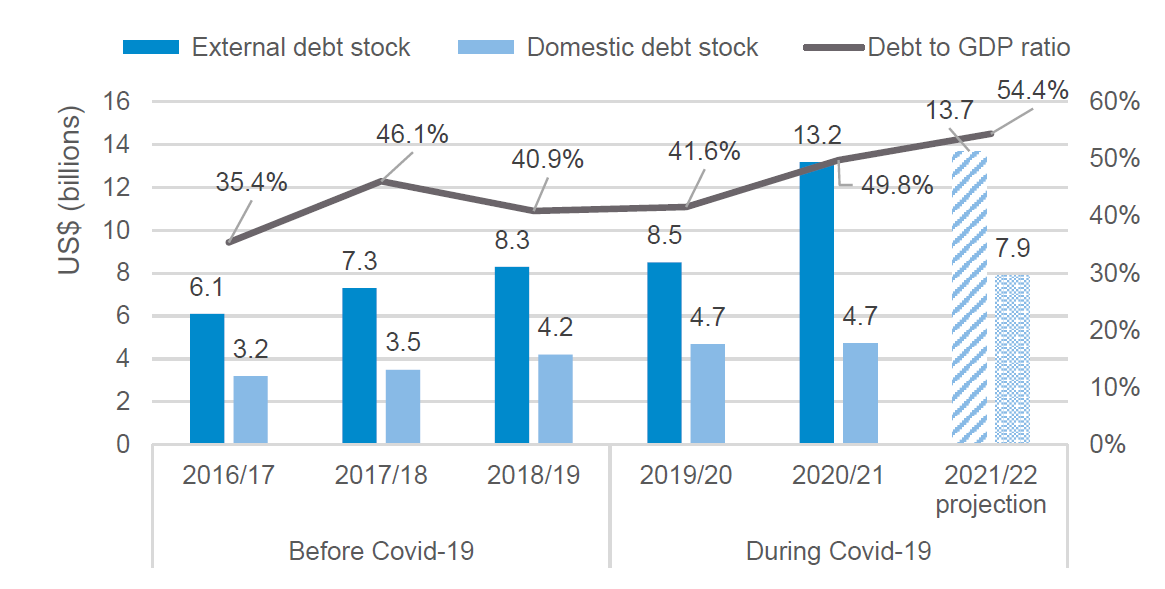

Public debt

Uganda’s public debt has grown significantly over the period from FY2006/2007 to FY2019/20. The growth rate of external public debt is higher than that of domestic debt over the same period. The recent increase in Uganda’s debt stock is largely associated with the emerging financing requirements to cover the shortfalls in revenue collection and Covid-related expenditure. Uganda also plans to approach creditors for debt repayment suspension for a given period. [32] The country’s public debt is projected to rise above 54% of GDP in FY2021/22 and peak at 59.6% of GDP in FY2023/24 [33] (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Uganda public debt composition, 2016/2017–2020/21

| External debt stock | Domestic debt stock | Debt to GDP ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Covid-19 | 2016/17 | 6.1 | 3.2 | 35.4% |

| 2017/18 | 7.3 | 3.5 | 46.1% | |

| 2018/19 | 8.3 | 4.2 | 40.9% | |

| During Covid-19 | 2019/20 | 8.5 | 4.7 | 41.6% |

| 2020/21 | 13.2 | 4.7 | 49.8% | |

| 2021/22 projection | 13.7 | 7.9 | 54.4% |

Source: Development Initiatives, based on data from the Ministry of Finance, the public debt report for FY2019/2020, the budget speech for FY2021/22 and the IMF Uganda country report 2020.

The observed widening of the fiscal deficit is warranted in the short term to allow for the implementation of Uganda’s Covid-19 response plan. This, however, puts Uganda at heightened debt vulnerability, even as the country signals to creditors for debt restructuring.

High levels of public debt require review of government expenditures, and efficient and effective domestic resource mobilisation and utilisation and an overall prudent fiscal policy management, as the country’s debt surges beyond 50% of GDP. [34]

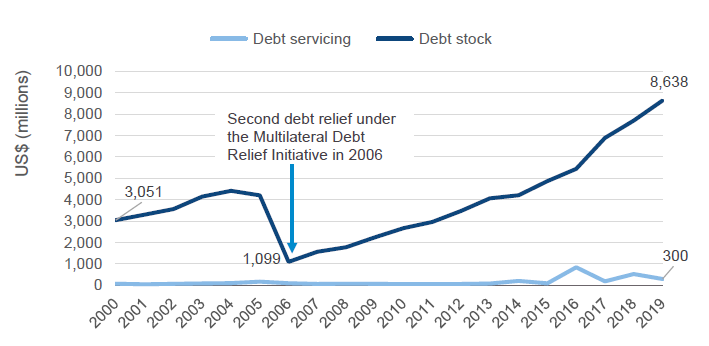

Debt servicing

Uganda’s debt stock continues to rise as the government continues to rely on borrowing to cover shortfalls in revenue collection and rising expenditure partly attributed to Covid-19. [35] However, Uganda’s debt servicing trend has largely remained stagnant across nearly two decades, while debt stock has increased significantly following the second debt relief received under the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative in 2006 (Figure 10). The World Bank’s multilateral debt-relief under the heavily indebted poor countries initiative reduced Uganda’s foreign debt from over $4.4 billion in 2004 to $1 billion in 2006. [36]

Figure 10: Volumes of annual debt and debt servicing, 2000–2019

| Year | Debt servicing | Debt stock |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 76 | 3,051 |

| 2001 | 51 | 3,305 |

| 2002 | 71 | 3,565 |

| 2003 | 91 | 4,150 |

| 2004 | 103 | 4,418 |

| 2005 | 172 | 4,209 |

| 2006 | 100 | 1,099 |

| 2007 | 67 | 1,571 |

| 2008 | 74 | 1,780 |

| 2009 | 72 | 2,247 |

| 2010 | 63 | 2,673 |

| 2011 | 64 | 2,963 |

| 2012 | 68 | 3,478 |

| 2013 | 88 | 4,064 |

| 2014 | 206 | 4,213 |

| 2015 | 95 | 4,869 |

| 2016 | 844 | 5,446 |

| 2017 | 188 | 6,890 |

| 2018 | 529 | 7,701 |

| 2019 | 300 | 8,638 |

Source: Development Initiatives, based on World Bank International Debt Statistics.

The share of the budget allocated to debt servicing through interest payments and amortisation between FY2015/16 and FY2019/20 more than doubles the combined total sector allocations to five key pro-poor sectors – education, health, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), agriculture, and social development – over the same period. This means that more money is being spent on managing debt than the delivery of services and development to people living in poverty under these sectors.

Conclusion and recommendations

By analysing Uganda’s domestic fiscal policies before and during Covid-19, this paper highlights several emerging trends, including budget allocations by sector, pro-poor sector gaps and requirements, domestic revenue inclusion projection of expenditure, public debt and debt servicing. The following conclusions are arrived at.

- Uganda’s domestic resource allocation to various pro-poor sectors pre-Covid-19 and during Covid-19 have increased marginally, while others like security have significantly changed. Of great concern on prioritisation during the pandemic is the decline in planned allocation for the social development sector, which supports vulnerable groups in Uganda.

- Funding gaps in pro-poor sectors such as education (38%), health (38%) and agriculture (18%) amid the pandemic (FY 2020/21) undermine the government’s ability to manage the immediate impacts of the pandemic on the poorest and address longer-term risks of increased vulnerability and leaving the poorest further behind.

- The pandemic has severely affected Uganda’s economy, reducing revenue collection by 18% in FY2019/20 and a projected 16% in FY2020/21.

- Uganda is not yet in debt distress, but with a public debt of US$17.96 billion by the end of FY2020/21, it is edging closer to debt unsustainability. While new borrowing is inevitable, public debt is rising and approached 50% of GDP by the end of FY2020/21.

- While the intention of joining other African countries to rally for debt repayment suspension will ease the debt stress for now, debt servicing and interest payments remain a big burden to Uganda with more funding already allocated to interest payment than key pro-poor sectors.

Recommendations

- The government of Uganda will have to look more at external sources in the short run to meet the required funding for its Covid-19 response, service delivery and development financing in the next one to four FYs.

- Uganda must urgently increase its domestic revenue collection capacity and improve fiscal management to slow down or stop the current debt stock growth.

- Innovative approaches for mobilising more domestic resources and their prudent utilisation should be desirable for better fiscal policy space.

Downloads

Notes

-

1

CNN, 11 June 21, 2021. Young people suffer most in Uganda’s second wave as country grapples with severe vaccine shortages. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2021/06/11/africa/uganda-vaccines-second-wave-cmd-intl/index.htmlReturn to source text

-

2

Africa news, 10 June 21, 2021. Uganda hospitals under pressure amid Covid-19 pandemic second wave. Available at: www.africanews.com/2021/06/10/ugandan-hospitals-under-pressure-amid-covid-19-pandemic-second-wave/Return to source text

-

3

American Public Health Association, 2020. Uganda as a role model for pandemic containment in Africa. Available at: https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305948Return to source text

-

4

Reuters, 5 August 2020. Uganda’s tough approach curbs Covid, even as Africa nears 1 million cases. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-uganda-idUSKCN251159Return to source text

-

5

Reuters, 2 June 2020. Uganda to lose $1.6 billion in tourism earnings as a result of COVID-19. Available at: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-uganda-tourism-idUSKBN2390XUReturn to source text

Related content

Aid data 2019–2020: Analysis of trends before and during Covid

What key shifts in donors, sectors, targeting and loans during the Covid pandemic are highlighted by new DAC data on 2019 ODA and 2020 aid figures from IATI?

Socioeconomic impact of Covid-19 in Uganda: How has the government allocated public expenditure for FY2020/21?

How will the Covid-19 pandemic affect people living in poverty in Uganda? This report looks at the Ugandan government's response measures in health, food, and water, sanitation and hygiene.

Coronavirus in Uganda: Current and future impacts

This podcast explores the Ugandan government's response to the coronavirus pandemic, the impact on citizens and the future prospects for the country.