Summary

The use of cash and voucher assistance (CVA) in humanitarian settings has grown significantly over the past decade. The adoption of CVA has been driven by donors and implementers alike, who largely agree that it can be a more cost-efficient way to deliver assistance than other delivery modalities, and that cash provides choice and dignity to affected populations. The growth in global volumes of humanitarian CVA is one of the few success stories of the Grand Bargain, increasing to around US$8 billion in transfers in each of 2022 and 2023.

Still, research suggests that there is yet more room for CVA to make up a greater share of international humanitarian assistance. [1] There also appears to be limited progress when it comes to connecting the localisation agenda with the delivery of CVA. A report by the Humanitarian Policy Group argues that the way in which the system absorbs “disruptive reforms” such as cash, “raises questions as to whether it will ever willingly concede power to the extent required for ambitions like localisation”. [2] Our analysis suggests that little progress has been made on financing to local and national actors when it comes to CVA, with the caveat that visibility over financial flows to local and national actors is limited. The original Grand Bargain text did not refer to the relationship between CVA and localisation, but the CVA Policy Dialogue initiative, co-convened by USAID and the CALP Network, is now putting locally led CVA on the agenda.

By humanitarian 'cash and voucher assistance' we mean the approach of providing support to crisis-affected populations in the form of cash and vouchers, enabling their greater choice and agency. We mostly do not include cash transfers provided through government-led social protection systems in response to crises due to limited data availability and comparability. See our ‘Methodology and definitions’, Chapter 5, for more on how we gather humanitarian CVA data with the CALP network and calculate humanitarian funding for CVA.

What is the trend in the volume of humanitarian cash and voucher assistance?

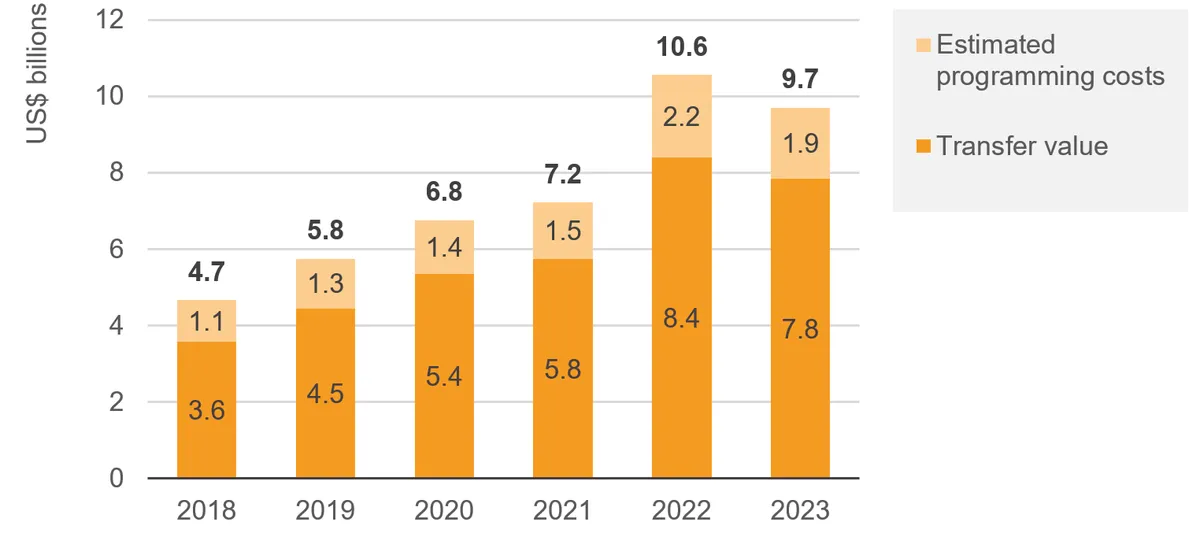

Figure 3.1: The volume of cash and voucher assistance declined for the first time in 2023 in line with overall funding for humanitarian responses

Funding for humanitarian cash and voucher assistance, 2018–2023

to come

Source: Data collected by the CALP Network from implementing partners supplemented by data from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)’s Financial Tracking Service (FTS) and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement’s Cash Maps.

Notes: Data for 2023 is preliminary as some organisations have not yet provided data or have provided partial data only. Double counting of cash and voucher assistance (CVA) programmes that are sub-granted from one implementing partner to another is avoided where data on this is available. Transfer values for funding captured on FTS are estimates based on the average ratio of transfer values to overall programming costs for organisations with available data. Data is not available for all included organisations across all years. Data is in current prices.

The volume of humanitarian CVA decreased in 2023 for the first time since Development Initiatives (DI) and the CALP Network started tracking global totals, with data going back to 2015. [3] The decrease in CVA assistance is reflective of the broader funding trend in the sector; international funding for humanitarian responses is under pressure (see Figure 1.3 in Chapter 1 ), and CVA is no exception.

- The amount of CVA transferred to people affected by crises declined from US$8.4 billion in 2022 to US$7.8 billion in 2023. Total funding, which includes both the transfer value and estimated programme costs associated with delivering cash or vouchers, similarly decreased from US$10.6 billion to US$9.7 billion. This decrease mirrors the overall trend in humanitarian financing.

- Despite this decrease, funding to CVA is still significantly higher than historical levels. Total CVA funding in 2023 was US$2.5 billion higher than in 2021, and the annual growth rate across the period (2018 to 2023) was 16% per year.

- This is in part due to where humanitarian CVA programming is possible. Past research has shown that context determines where and how much CVA can be implemented. [4] For example, the large-scale use of cash in the Ukraine response continues to contribute to the uplift in overall CVA volumes – despite signs that volumes in Ukraine may have dipped in 2023.

Humanitarian CVA continued to grow in importance as part of the humanitarian sector in 2023, despite the slight decrease in financial volumes.

- CVA constituted an estimated 23% of total international humanitarian assistance in 2023, compared to 22% in 2022. This is a significant increase from our estimate for 2017 (16% of total international humanitarian assistance). It should be noted that the total CVA volume cannot be directly compared to the total humanitarian assistance volume in Chapter 1. This is due to the different methodologies and data sources used to calculate CVA compared to overall volumes of international humanitarian assistance. The former is primarily based on data directly collected from implementing actors, while the latter is calculated based on data – mostly from public reporting platforms – on funding provided by donors.

As the nature of humanitarian response shifts towards being more protracted and impacts of climate change increase, links across the humanitarian–development–peace nexus become even more pressing. While data on cash is becoming more visible over time (see the next sub-section), there is a lack of comparable data on social protection transfers to crisis-affected populations in protracted humanitarian contexts. The International Labour Organization’s World Social Protection Report 2024–26 argues that social protection contributes to climate change mitigation and adaptation, [5] which is especially relevant to most humanitarian crisis countries that face high risks of disruptions from climate change. [6]

- Humanitarian cash and social protection systems are often fragmented and involve different actors, funding streams and coordination structures. However, they often share objectives and operate in the same geographies.

- Despite this, the lack of data on the volume of social protection payments transferred to people affected by crises is a blind spot when discussing humanitarian cash, as both CVA and social protection payments to the same populations should be considered together. As the latest State of the World’s Cash report notes, there is a lack of a shared understanding over how to categorise cash-based social assistance as ‘humanitarian’. [7]

- This lack of comparable data also means there is limited visibility on the role of national governments in responding to crisis and disasters.

DI is currently working with the Institute of Development Studies to identify the volume of international financing directed to social protection in protracted crisis settings.

Who delivers cash and voucher assistance, and how?

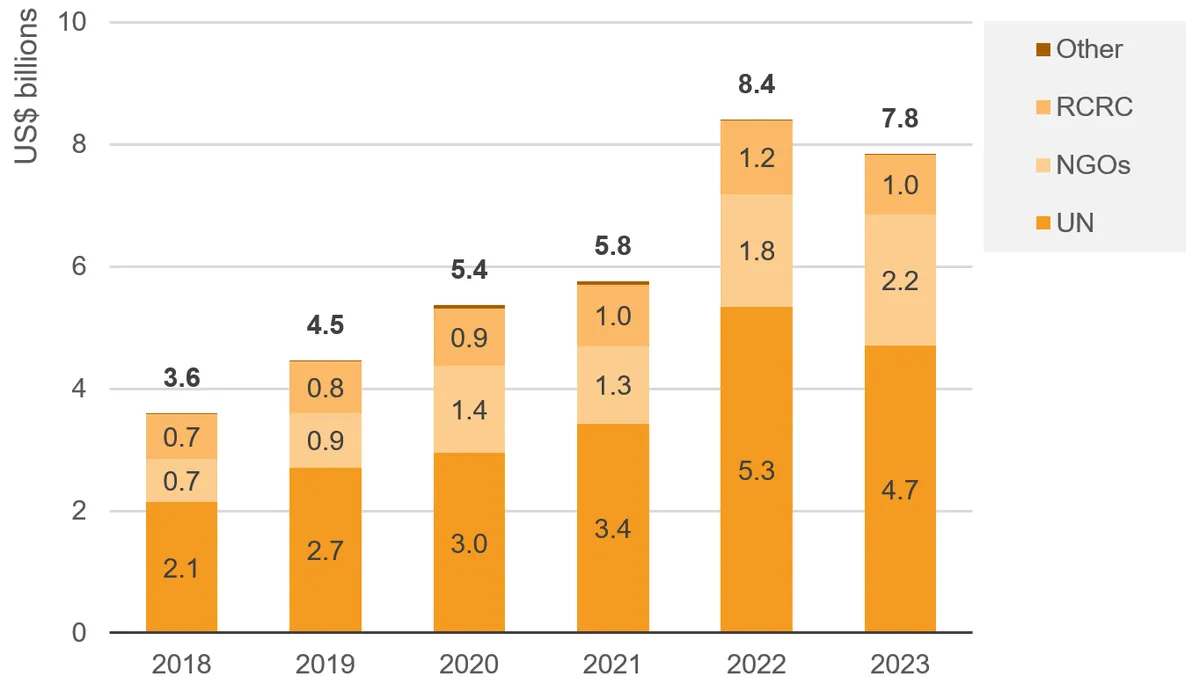

Figure 3.2: UN agencies continue to deliver the most cash and voucher assistance

Total humanitarian cash and voucher assistance transfer values, 2018–2023

to come

Source: Data collected by the CALP Network from implementing partners supplemented by data from UN OCHA’s FTS and the RCRC Movement’s Cash Maps.

Notes: Data for 2023 is preliminary as data for some organisations has not yet been provided or is partial. Double counting of CVA programmes that are sub-granted from one implementing partner to another is avoided where data on this is available. Transfer values for funding captured on FTS are estimates based on the average ratio of transfer values to overall programming costs for organisations with available data. Data is not available for all included organisations across all years. Data is in current prices.

UN agencies continue to be the primary channel of delivery for CVA, followed by NGOs and the International Red Cross and Red Crescent (RCRC) Movement.

- UN agencies delivered US$4.7 billion in CVA in 2023, a 12% decrease compared to 2022; meanwhile, NGOs delivered US$2.2 billion in CVA, a 17% increase.

- While this may appear to be a substantial shift in who delivers CVA, the UN still constitutes a similar percentage to its historical average. Between 2018 and 2022, the UN delivered 60% of CVA each year on average, while in 2023 the UN delivered 61%. However, NGOs delivered 28% of CVA in 2023 (an increase on their 2018–2022 average of 22%). At the same time, the percentage delivered by the RCRC declined to 12% (lower than its 2018–2022 average of 17%). This is within the context of budget constraints across the RCRC Movement in 2023 and a reduction in global costs by ICRC of just under US$0.5 billion in 2023 and 2024. [8]

- This reflects the broader sector. Analysis in Chapter 2 shows that 58% of funding from Grand Bargain donors was channelled through multilaterals, while our analysis here shows that UN agencies delivered 61% of the total cash and voucher transfer value in 2023.

Data on the amount of CVA delivered by local and national actors remains sparse but indicates a low percentage of funding going to local and national actors.

- Limited data shows that 2.1% of CVA can be identified as being delivered by local and national actors in 2023.

- The majority of CVA identified as being delivered by local and national actors comes from data regarding sub-grants (i.e. through intermediaries), and this is an incomplete picture. However, the amount of direct funding we can identify, using the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)’s Financial Tracking Service (FTS), as going to local and national actors is negligible.

The true amount of CVA delivered by to local and national actors is likely to be higher than the data suggests. However, as noted in Chapter 2, without greater transparency by international intermediaries it is unclear how much and in which contexts local and national actors are delivering CVA.

The trend towards cash constituting an increased percentage of all CVA has persisted in 2023.

- In 2023, 81% of CVA was delivered in the form of cash assistance and 19% was delivered in the form of vouchers.

- This continues the uptick seen in 2022, when 80% was delivered in the form of cash assistance, an increase on the 2019–2021 average of 71%.

- As noted in the Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2023 , the scale of the Ukraine response in 2022 contributed to the broader shift towards cash as the preferred modality across the sector. Data from UN OCHA’s FTS suggests this dynamic carried through into 2023 as large amounts of funding to CVA persist in Ukraine in 2023.

Box 3.1

Challenges in tracking humanitarian cash and voucher assistance

The data available to track humanitarian CVA is still scattered, not easily accessible and incomplete. This section uses data from a survey of organisations collated by the CALP Network. DI then supplements this survey data with data from UN OCHA, which integrates data from the FTS and the HPC Project Module portals, and uses machine learning to identify CVA. Together, these sources of data provide the best available picture of CVA volumes.

Not all CVA is reported to the publicly available platforms such as FTS. Using a range of methods, DI was able to identify an estimated US$4 billion in CVA through the FTS in 2023, 41% of the estimated total volume of CVA. However, using just the column that identifies ‘Cash transfer programming’, only US$2.6 billion can be identified in 2023 – 27% of the total volume.

This matters. Without reporting to public platforms such as the FTS, organisations, coordinators, technical specialists and implementers are not able to answer key questions. Where is CVA implemented? Who is it going to? Who is funding CVA?

This in turn hampers coordination in the humanitarian system and the ability of humanitarians to identify gaps in cash and voucher programming and to target funding for CVA where it is lacking.

Local and national actors are also not visible in the CVA financing data due to the lack of publicly available data, and thus it is hard to know the extent of their role in the international CVA space.

How does cash and voucher assistance fit in the wider picture?

CVA is not delivered uniformly across all humanitarian contexts. Some contexts may be more suited to the use of CVA as a delivery modality particularly where markets function well, recipients can be easily identified and registered, and well-established payment systems are in place. In other contexts, a lack of these conditions can make CVA more challenging, together with national government policies, protection risks and donor risk appetites.

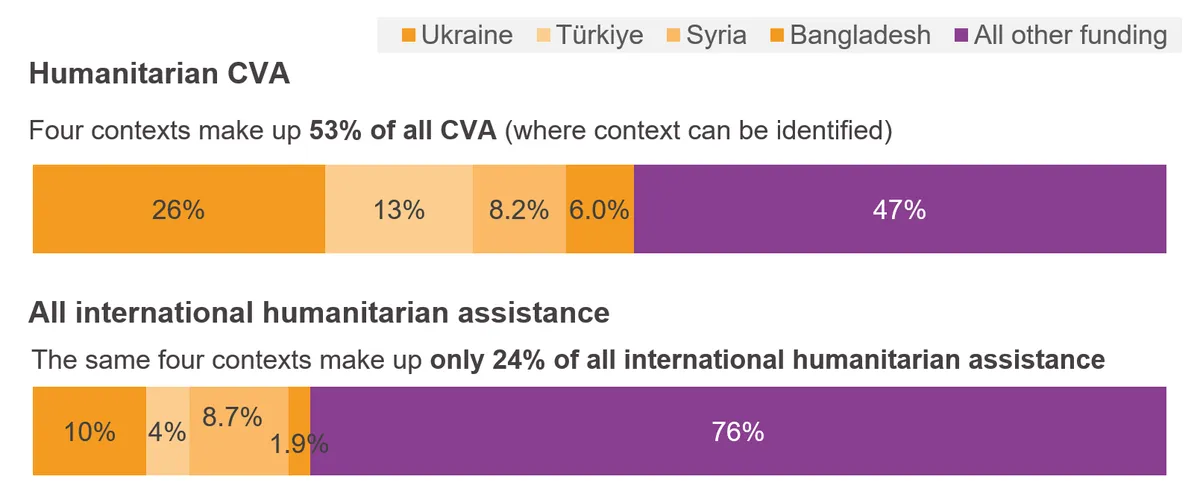

Figure 3.3: Cash and voucher assistance is concentrated disproportionately in a small number of contexts according to available data

Proportion of a) CVA and b) all international humanitarian assistance to Ukraine, Türkiye, Syria and Bangladesh, 2023

to come

Source: UN OCHA’s FTS and HPC Project Module.

Note: The CVA data used here is different to that used to analyse overall CVA volumes above, as OCHA’s FTS enables analysis by location due to the disaggregation of CVA funding flows. The CVA data represents US$4 billion in volume and is therefore a subset of total CVA volumes and may only provide a partial view.

Using UN OCHA’s FTS, CVA financing could be identified for around US$4 billion in financial flows in 2023. This represents 41% of global volumes of humanitarian CVA. In this dataset, four contexts represented 53% of CVA in 2023: Ukraine, Türkiye, Syria and Bangladesh. The same four contexts only constitute 24% of all humanitarian assistance. This suggests that, when compared to the broader humanitarian sector, the use of cash is even more concentrated in a smaller number of humanitarian responses than international humanitarian assistance overall. It also supports the argument that the growth of humanitarian CVA depends on how big a role this delivery modality plays in the crisis responses that attract a large share of funding.

Moving from emerging trend to maturity: Conclusion and recommendations

The use of CVA in humanitarian assistance has greatly expanded over the past decade. However, 2023 data suggests that this growth could be stalling. Whether it is a temporary dip in a long-term upward trajectory, or the start of a plateau in CVA financing, this raises a number of questions.

Firstly, with CVA rising to 23% of all assistance in 2023, will it continue to become even more important? Our updated data shows that in 2017, an estimated 16% of total humanitarian assistance was delivered through CVA. This rise, not just in absolute volumes, but as part of the wider sector, is impressive. But this begs the question, what next when the sector is undergoing a financial crunch? And is it realistic for cash to continue to become an even bigger part of the sector?

Secondly, could there still be room for CVA to grow and meet the needs of different affected populations? CVA’s concentration in a small number of contexts suggests that while it has grown substantially in recent years, this growth is geographically uneven. There may be good reasons for this, such as a better enabling environment for the use of CVA in some contexts over others. However, this may also mean that cash is being underused in some contexts – more research and reporting on CVA may be needed to examine if this is the case. The CALP Network has argued that cash could be an answer to the humanitarian financing crunch as it “offers an opportunity of making substantial cost savings and the possibility of reaching more people with more assistance”. [9]

Thirdly, does the existing use of CVA support or hinder localisation efforts? Despite the upward trend in overall CVA funding, the percentage going to local and national actors mirrors the humanitarian system as a whole, at least so the available data shows. UN agencies continue to dominate the CVA landscape and our analysis can identify 2.1% going to local and national actors. Greater focus needs to be on making sure local and national actors are not bypassed, and that their role in delivering CVA is more visible. At the same time, as Christian Aid has argued, locally led CVA responses also need to be recognised as a distinct approach and funding stream. [10]

Grand Bargain signatories must:

- Increase the transparency of humanitarian CVA financing data to public platforms, such as the FTS, to enable greater visibility of disaggregated data. This is crucial to enable breakdown by geography, cluster and organisation type and thus improve planning and coordination of cash and voucher responses.

- Explore whether all opportunities have been optimised for the use of CVA across contexts, not just the small number of geographies where it is currently concentrated.

- Agree on and implement concrete actions to make the delivery of CVA more locally led. These actions should include: ensuring full visibility of local and national actors facilitating the delivery of CVA as sub-grantees; increasing direct funding to local and national actors for CVA programmes; strengthening links between humanitarian CVA and national social protection systems where possible; and increasing the use of group cash transfers.

Insight

CVA's stalling growth, challenges and opportunities

Ruth McCormack is a Global Technical Advisor with the CALP Network (and the network’s focal point for CVA volume data tracking and analysis). She has worked in the humanitarian sector for nearly 20 years. Before joining CALP, she worked with several organisations across multiple responses, including in Malawi, South Sudan, Kenya, Palestine, Jordan and the Philippines.

Crys Chamaa is a Global Technical Advisor with the CALP Network. She co-leads the Cash and Locally Led Response Working Group and is secretariat to the Group Cash Transfers Working Group. She has more than a decade of experience in the humanitarian sector, and has worked in emergency, protracted crises and conflict settings.

CVA volumes increased annually from 2015 to 2022. As such, 2023 is notable in seeing the first drop in CVA volumes – an 8% reduction from US$10.6 billion in 2022 to US$9.7 billion in 2023. As this report finds, this is unsurprising in that it reflects 2023’s decrease in overall humanitarian funding; it also follows a dramatic 47% increase in CVA volume in 2022, driven by factors including the Ukraine crisis and responses to rising global food insecurity. Despite the decrease it is positive news that, in a challenging global context, CVA increased in 2023 as a share of international humanitarian assistance, albeit incrementally from 22% to 23%. This aligns with the relatively slower rate of growth in CVA as a share of international humanitarian assistance since 2020.

The evolution of CVA from less than 1% of assistance 15 years ago to 23% now was both facilitated by and helped drive significant and multifaceted shifts in the humanitarian system. We remain, though, some way off CVA comprising the 30–50% of international humanitarian assistance it could if used wherever feasible and appropriate. [11] Optimising the use and quality of CVA remains a key opportunity for enabling choice and dignity and responding to people’s preferences. It can also drive greater aid efficiency and effectiveness in a constrained funding environment.

Gradual improvements in data and reporting have been important in tracking progress, although the primary focus should be the impact of CVA for communities affected by crises, rather than growth in itself. CVA provides a lens that can highlight both systemic challenges and opportunities for improvement, for example by providing more comprehensive and contextualised support to affected populations. These range from social protection links to locally led response to anticipatory action – where cash is the most frequently used modality. [12] These forms of assistance, which are not generally tracked as ‘humanitarian CVA’, also point to some of the limitations of existing CVA data, and to the fragmentation of funding and aid structures.

Data on CVA funding to local and national NGOs is patchy at best, and their role in implementing CVA often goes unrecognised with limited visibility. Direct funding is marginal and progress towards better partnerships through more equitable funding, including overhead costs, also shows limited movement. It has been argued that while institutionalisation across many international actors has supported growth to date, this has also enabled the system to co-opt CVA, restricting scope and flexibility, including for better contextualisation and locally led responses.

Perspectives on the future of CVA are divergent. Some feel CVA has been effectively institutionalised and the ‘battle is won’. However, others sense fragility in the progress to date, with multiple dynamics and factors indicating a need to continue strengthening the case for CVA and be mindful of challenges. Moreover, a recent ODI study [13] posits that the full transformative potential of cash has not been reached and faces risks. Upcoming CALP-commissioned analysis also highlights the ‘unfinished business’ of cash in making meaningful progress in shifting power and agency to people affected by crisis. Further substantive changes are still needed in the underlying structures, mindsets and day-to-day processes of the humanitarian system if cash is to fulfil its potential. As identified through CALP’s CVA Policy Dialogue, [14] this requires a refreshed collective effort and commitment from all stakeholders.

Downloads

Notes

-

1

CALP Network, 2022. Increasing the Use of Humanitarian Cash and Voucher Assistance: Opportunities, Barriers and Dilemmas. Available at: www.calpnetwork.org/publication/increasing-the-use-of-humanitarian-cash-and-voucher-assistanceReturn to source text

-

2

Humanitarian Policy Group (HPG) Working Paper, 2024. Change without transformation: how narratives influenced the humanitarian cash agenda. Available at: https://odi.org/en/publications/change-without-transformation-how-narratives-influenced-the-humanitarian-cash-agendaReturn to source text

-

3

The volume of CVA, as well as the volume of international humanitarian assistance, published in this report may be different from that published in other reports, such as previous Global Humanitarian Assistance reports and State of the World’s Cash reports. This is due to several reasons. Firstly, DI has deployed machine learning methods to capture CVA in all previous years in the analysed period. This has enabled a greater proportion of previously ‘invisible’ CVA to be captured in this year’s methodology. Secondly, total international humanitarian assistance numbers may differ from previous years due to updated data. Data from OECD DAC for the previous year is considered provisional, and thus has been updated. Data from UN OCHA’s FTS is subject to change between different reports as well because it is a ‘live’ database of financial flows.Return to source text

-

4

CALP Network, 2022. Increasing the Use of Humanitarian Cash and Voucher Assistance: Opportunities, Barriers and Dilemmas. Available at: www.calpnetwork.org/publication/increasing-the-use-of-humanitarian-cash-and-voucher-assistanceReturn to source text

-

5

International Labour Organization, 2024. World Social Protection Report 2024-26: Universal social protection for climate action and a just transition. Available at: www.ilo.org/publications/flagship-reports/world-social-protection-report-2024-26-universal-social-protection-climateReturn to source text