Falling short? Humanitarian funding and reform: Chapter 2

Funding to local and national actors

DownloadsSummary

Humanitarian funding continues to be distributed largely to multilateral actors and international NGOs, despite years of efforts through the Grand Bargain to increase the proportion of funding to local and national actors. This year, across the humanitarian system, the overall volumes of funding for localisation have increased, due to new direct allocations by non-Grand Bargain donors. Yet the full picture of how much funding reaches local and national actors remains obscure, despite increased commitments made by intermediary organisations in 2023 to improve data transparency.

Progress has been made on the provision of overheads to local and national actors, with new policies adopted by four different Grand Bargain signatories over the past year. But overall, progress on localisation remains patchy, with little meaningful change in terms of access to quality financing for first responders.

By 'funding for local and national actors' we mean funding to local or national NGOs, to local or national governments and to Red Cross or Red Crescent National Societies in line with the definitions agreed within the Grand Bargain. [1] Southern international NGOs, which receive funding to operate within the country they are headquartered in, are included as national actors. Red Cross Red Crescent (RCRC) National Societies and local or national governments that received international humanitarian assistance to respond to domestic crises are included only when contributing to the domestic crisis response.

In 2016, the Grand Bargain set a target of providing 25% of global humanitarian funding to local and national responders ‘as directly as possible’ (i.e. through up to one intermediary to local and national actors). However, funding often passes through additional intermediary organisations, and this indirect subsequent funding is still not publicly reported by many actors, meaning it is subject to is limited tracking and transparency. See our ‘Methodology and definitions’, Chapter 5, for more detail.

Is funding to local and national actors increasing?

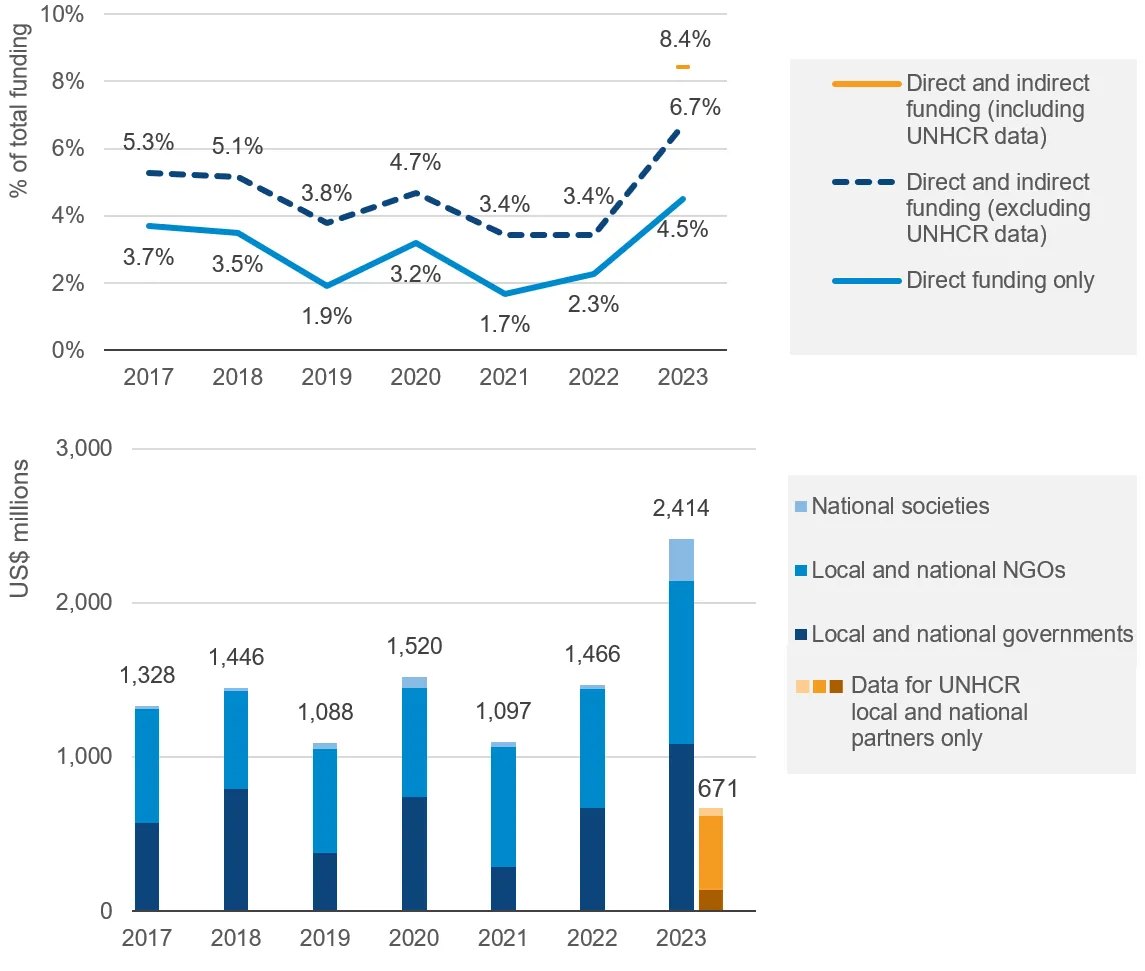

Figure 2.1: Funding to local and national actors has increased significantly due to large direct allocations from Gulf actors for specific crises

Proportion and total volumes of direct and indirect funding to local and national actors, 2017–2023

to come

Source: DI based on UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)’s Financial Tracking Service (FTS) data, country-based pooled funds (CBPFs) data hub and UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) 2023 partner budget information.

Notes: See our ‘Methodology and definitions’, Chapter 5, for more information on the identification of local and national actors. Data is in constant 2022 prices.

In 2023, funding to local and national actors increased for the first time in five years. However, this is due to large direct funding flows from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) to specific country responses.

- In 2023, US$1.7 billion was directly allocated to local and national actors, an increase of 71% over 2022 (US$970 million), from 2.3% [2] to 4.5% of all trackable humanitarian funding.

-

This increase in funding can be attributed to two donors:

- The Saudi Arabian government provided US$761 million, of which US$309 million went directly to the Ukrainian government and US$330 million to the Government of Yemen.

- The Red Crescent Society of the UAE, previously a very limited reporter to the Financial Tracking Service (FTS), provided US$236 million to the Syrian Arab Red Crescent, a mix of in-kind and financial assistance. [3]

Assessing the overall picture of direct and indirect funding remains challenging. Last year, Grand Bargain members of the Caucus on funding for localisation, as well as several signatories, committed to full transparency of funding flows to all partners, in particular local and national actors, to better enable accountability efforts in line with the 25% target. [4] Data transparency on funding through one intermediary to local and national actors – which counts towards the Grand Bargain 25% target by qualifying ‘as directly as possible’ – has improved slightly thanks to new reporting practices by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). It now publishes granular data on its partnerships that can be independently verified against Grand Bargain definitions of local and national actors [5] (although there is room for improvement in terms of format accessibility and reporting frequency).

By doing this, the UN Refugee Agency has paved the way for other multilateral agencies to provide greater transparency on funding flows, in line with Grand Bargain commitments and a sector-wide demand for data on how financial resources move through the system. However, given this new data for 2023, overall volumes of direct and indirect funding based on granular data between 2022 and 2023 are no longer comparable, further pointing to the need for sector-wide adherence to reporting commitments.

- All trackable direct and indirect humanitarian funding to local and national actors in 2023 totalled an estimated US$3.1 billion, based on data for direct flows (FTS) and partial data for indirect flows (including FTS, country-based pooled funds’ allocations and UNHCR data).

- This was 8.4% of all trackable humanitarian flows in 2023. However, 2023 is the first year for which data from UNHCR is available, rendering comparisons of this figure with previous years impossible without excluding UNHCR.

- Excluding data from UNHCR, the share of total direct and indirect funding that went to local and national actors is 6.7% – an increase of 65% from 2022 to 2023. This is largely due to large volumes of funding provided by the Saudi Arabian government and the Red Crescent Society of the UAE as mentioned above.

- Indirect funding to local and national actors totalled US$1.4 billion (4.0% of total funding) in 2023, of which almost half (US$671 million) is newly reported funding provided by UNHCR to its partners.

There was a shift in the proportions of total global direct and indirect humanitarian funding provided to different local and national groups in 2023, again due to the large new volumes of funding from Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

- Local and national governments received US$1.2 billion in funding, representing 40% of trackable localised funding, a similar share as in 2022.

- Local and national NGOs received US$1.5 billion (50%) of all trackable localised funding in 2023, a drop from 53% in 2022.

- National Red Cross Red Crescent (RCRC) Societies received the remaining US$330 million (11%), which was a sharp increase from the US$23 million received in 2022, largely due to the contributions from the Red Crescent Society of the UAE to the Syrian Arab Red Crescent.

- While most funding to local and national governments (88%) and National RCRC Societies (82%) was made directly, just 20% of funding was made directly to local and national NGOs, with the remainder passing first through at least one intermediary.

- UN country-based pooled funds (CBPFs) represented 11% of total global funding to local and national actors that was independently verifiable in 2023, at US$329 million.

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)’s CBPFs – which provide highly transparent data on funding allocations and sub-grants – continued increasing their share of funding to local and national actors, although overall volumes decreased.

- In 2023, CBPFs channelled 30% (US$327 million) of subsequent funding to local and national actors, a 2.3% increase from 2022 (although this represented a US$52 million decrease in volume).

- International NGOs received 44% (US$482 million) of subsequent funding from CBPFs, and multilateral organisations received 25% (US$276 million).

- In 2023, the Venezuela CBPF channelled the largest proportion of its subsequent funding to local and national actors, at 72% (US$8.4 million), an increase from 61% in 2022. Somalia and the Syria Cross-border Humanitarian Fund also saw increases, from 61% to 69% (a total of US$38 million) and 42% to 55% (a total of US$74 million in total) respectively.

- The Lebanon CBPF saw the largest increase in its proportion of funding channelled to local and national actors from 21% in 2022 to 39% in 2023.

- The CBPFs with the lowest percentages of funding to local and national actors (excluding Iraq and Jordan) [6] were the Sudan fund (4.5%, US$3.5 million) and the South Sudan fund (9.1%, US$4.9 million).

- Of the 19 CBPFs active in 2023, 10 (53%) allocated at least a quarter of funding to local and national actors directly. This is an increase from 2022, when 9 of 20 (45%) active CBPFs reached this target.

The Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) can only fund UN agencies, and therefore its sub-granted funding to local and national actors technically does not count towards the Grand Bargain target as it is channelled through two intermediaries (CERF and then UN agencies). However, subsequent funding to local and national actors, which had previously been on the rise, has reduced.

- In 2023, 10% (US$69 million) of CERF allocations were sub-granted to local and national actors. This is a decrease from 12% (US$89 million) in 2022.

While most ‘first-level’ funding (i.e. received directly from a donor) that goes to pooled funds is directed to the UN CERF and CBPFs, other pooled funds seek to provide greater funding and autonomy to local and national actors. Locally led humanitarian funds allow organisations with the relevant contextual knowledge to make decisions about how money is spent. Examples include the regional Consultative Group of Risk Management fund in Central America, the Community Resilience Fund in Nepal, the NEAR Change Fund and the Syria-Türkiye Solidarity Fund. In such funds, local and national implementers’ involvement is protected and prioritised, and where possible local and national NGOs can adapt funding to changes in the context, allowing for greater flexibility. Some examples of NGO-led crisis response funds include the Sahel Regional Fund, the Human Mobility Hub, the Nabni Building for Peace facility, and the Global Start Fund. These funds focus on obtaining flexible and predictable funding, which is then allocated to NGOs to complement existing work to fill specific gaps in crisis response. [7]

How are Grand Bargain signatories channelling humanitarian funding?

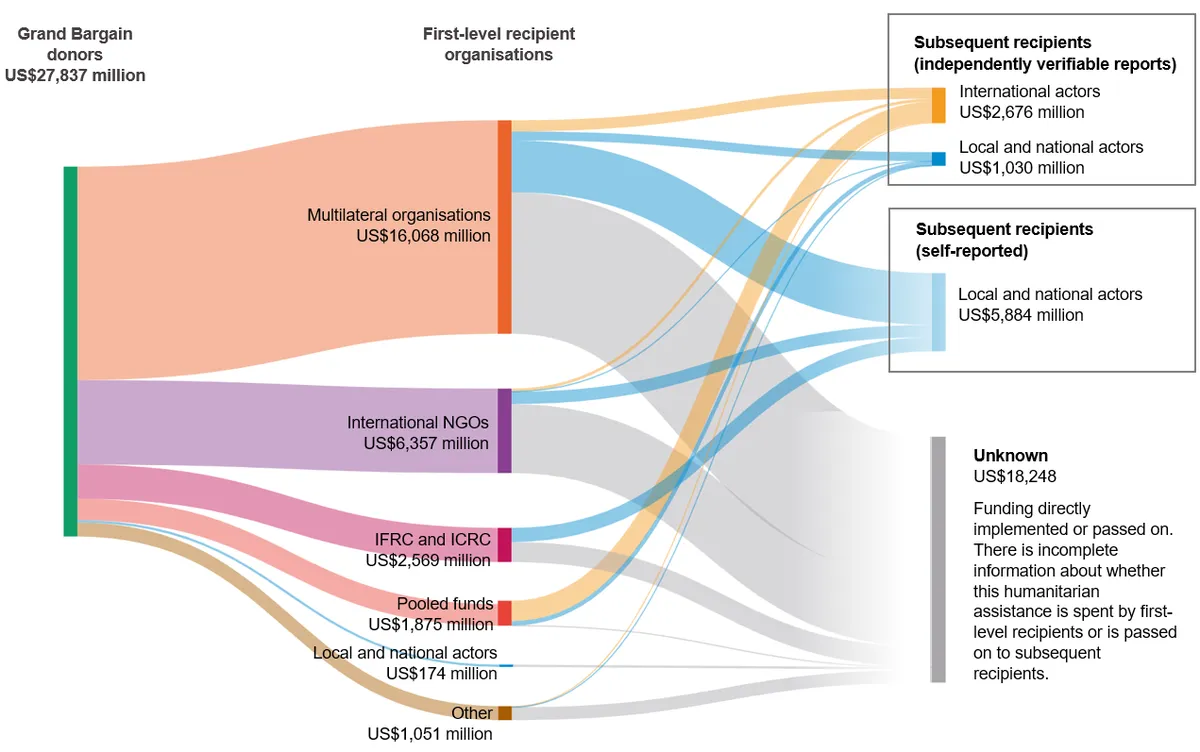

Figure 2.2: Multilateral organisations continue to receive the largest share of international humanitarian assistance, while transparency on funding to subsequent recipients remains challenging

Channels of delivery of international humanitarian assistance from Grand Bargain public donors, 2023, to first-level and subsequent recipient organisation types

to come

Source: Development Initiatives (DI) based on OCHA FTS data, CBPFs and Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) data hubs, UNHCR 2023 partner budget information and Grand Bargain 2024 self-reports.

Notes: ‘First-level funding’ refers to funding received directly from a donor.’ Funding received via subsequent recipients’ refers to funding received through one or more intermediary organisations. Data is in constant 2022 prices.

In 2023, there were no major changes in direct funding patterns of Grand Bargain signatories. Most funding the Grand Bargain signatory donors reported to FTS was directly channelled to multilateral institutions and international NGOs.

- In 2023, 58% of all funding from Grand Bargain signatory donors went directly to multilateral institutions and 23% was channelled to international NGOs.

- Of funding to multilateral donors from Grand Bargain signatory donors and captured on FTS, 74% was received by just three multilateral institutions. The World Food Programme received 45% (US$7.2 billion), the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) received 17% (US$2.7 billion) and UNICEF received 13% (US$2.1 billion). This distribution has remained consistent since 2018.

- The International RCRC Movement received 9% of funding.

- Pooled funds received 5.8% of first-level funding (received directly from Grand Bargain donors). Of this, 66% went to CBPFs and 32% went to the UN’s Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF).

In terms of progress on localisation, large donors such as USAID and the Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (DG ECHO) have published new localisation strategies. However, despite the longstanding Grand Bargain commitment to provide an aggregate of 25% of all funding to local and national actors (either directly or via up to one intermediary), little progress has been made in terms of direct funding. This is in line with the longer-term trend evident since the early stages of the Grand Bargain.

- In 2023, local and national actors directly received US$174 million, accounting for only 0.6% of all first-level funding from Grand Bargain donors. This represents a slight increase from 0.5% in 2022.

- While total global funding from Grand Bargain signatories has increased by US$7.8 billion since 2018 (from US$20 billion to US$27.8 billion), direct funding to local and national actors has increased by only US$74 million.

- Of the direct funding to local and national actors from Grand Bargain donors in 2023, around two-thirds (US$115 million) went to local and national NGOs.

- A fifth (US$39 million) went to national or local governments and the remainder (US$20 million) directly to National RCRC Societies responding in the countries where they are based.

- This distribution is roughly in line with the average annual share of direct funding to each of those groups since 2018.

There remains a significant gap in understanding progress on the localisation funding target in terms of indirect funding to local and national actors. Large volumes of funding from intermediaries to subsequent recipients are only reported in aggregate in organisations’ annual reports or Grand Bargain self-reports, and remain without independent scrutiny, despite renewed commitments to provide greater transparency. [8] As mentioned above, newly available data from UNHCR on their partnerships, including with local and national actors, slightly improved the transparency of subsequent funding. However, including the self-reported data by Grand Bargain intermediaries paints a different picture of much greater funding volumes to local and national actors:

- Based on independently verifiable and publicly reported data, Grand Bargain signatories provided 4.4% of their direct and indirect funding to local and national actors in 2023. However, this figure includes new data provided by UNHCR and is therefore incomparable with data from 2022.

- Excluding UNHCR data, direct and indirect funding from Grand Bargain donors to local and national actors (as a proportion of the total they provided) increased slightly from 1.6% in 2022 to 1.9% in 2023.

- When also including data on funding to local and national actors from the Grand Bargain intermediaries’ self-reports – which are not possible to verify independently – the share of all funding from Grand Bargain signatories channeled to local and national actors in 2023 rises to 25%. This stands in stark contrast with the much lower share based on independently verifiable data and raises the question where this funding is directed and whether the self-reported figures align with the agreed Grand Bargain definitions, underlying the urgent need for improved public reporting.

What progress was made on the provision of overheads?

Aside from the quantity of funding reaching local and national partners directly or through intermediaries, there is a growing emphasis on the quality of that funding and partnerships. Part of this discussion is the historically limited ability of local and national actors to recover their indirect costs and secure overheads funding to strengthen organisational core capacities.

After years of sustained advocacy from local and national actors in favour of the sharing of overheads or indirect costs, the IASC issued guidance for its members [9] in late 2022 based on research carried out by Development Initiatives (DI) [10] and Grand Bargain signatories committed to allocating overheads through the Caucus on the role of intermediaries. Two years later this momentum continues, as increasing numbers of donors and international intermediaries publish policies and change their practices on indirect cost recovery for local and national actors. This is part of broader efforts by signatories to revise their partnership policies and models – on overheads and other aspects of their funds – and collaborate with their partners, in particular local and national actors. However, based on information collated by DI, while at least four signatories adopted new policies in the past year, more than half of the Grand Bargain signatories still lack publicly available policies that institutionalise equitable cost recovery for local and national partners. [11]

- Of the 25 Grand Bargain government donors, 5 have policies in place. This includes the German Federal Foreign Office (GFFO), which committed to a new policy within the last twelve months and, like USAID, has increased the percentage of indirect cost recovery it offers. An additional 4 governments are developing their policies, and 5 operate with guidelines in place.

- Of the 12 UN agencies, 9 have provided DI with policy details and 8 have policies in place. This includes the World Health Organization, which has newly adopted a policy. An additional UN agency is continuing to develop its policy on partner overheads.

- Of the 26 NGOs, 13 have committed to a policy, 3 of which were new over the past year (CARE, Catholic Relief Services and the Danish Refugee Agency). There are 5 organisations developing policies; 4 of these have been doing so for over a year.

- The International RCRC Movement does not have policies or has not reported policies specific to this issue. However, the ICRC provides its National Society partners with 7% of overheads and the IFRC is piloting an approach, with support of key donors, that allows its local partners to recover 6–7% of indirect costs.

The widespread adoption of policies by a range of Grand Bargain signatories enabling a more equitable cost recovery for local and national partners is a welcome step. However, these policies vary in terms of quality and implementation, and feedback from local partners still indicates inconsistent application of newly adopted policies. The policies also vary in the percentage of indirect costs covered for local and national partners, but commonly range from 4% to 12%.

- USAID and NEAR stand out among Grand Bargain signatories as they provide an indirect cost rate of up to 15%.

- For comparison with humanitarian funders outside the Grand Bargain, some private foundations provide 25% to local and national actors.

The stalling of the localisation agenda: Conclusion and recommendations

In line with findings from Development Initiatives’ 2017–2023 annual Global Humanitarian Assistance reports, despite strong sector-wide commitments to providing increased levels of funding to local and national actors, independently verifiable data shows little visible change across the sector. As the humanitarian system reaches its tipping point – with refocusing and prioritisation affecting sector-wide budgets – and with the Grand Bargain in its ninth year, a new and realistic conversation is needed about what continues to hamper meaningful progress on the localisation imperative.

Furthermore, despite the 2023 endorsement of the outcomes of the Caucus on funding for localisation – in particular the monitoring and accountability framework [12] drafted by DI – obtaining a clear picture of funding flows to local and national partners and tracking the aggregate 25% target remains impossible. This is mostly because of a continued lack of transparency by most intermediaries. The self-reporting exercise of the Grand Bargain provides some insight into current practices, but this data is in global, organisational totals and provided retrospectively. This makes it impossible to verify independently and the data has limited use for local and national groups at country level that are trying to understand how funding flows through the humanitarian system in their crisis context. In addition, several signatories continue to publish data that does not align with Grand Bargain definitions. USAID, for example, is leading the way in terms of its organisational commitment to localisation and transparency around its progress, but applies its own internal metric which differs from other signatories. [13] To ensure progress on this commitment, the largest humanitarian actors must work on ensuring full transparency on how much funding is being provided and to whom.

Without greater transparency, it is impossible to gauge and have informed discussions about the quality of such funding. However, one area where progress can be seen is on the provision of overheads, where DI continues to be involved in the roll-out and monitoring of the IASC Guidance on the Provision of Overheads to Local and National Partners. [14] In 2023, 37% of Grand Bargain signatories had policies in place to ensure cost recovery from local and national partners. There is also a growing evidence base on locally led and international funding mechanisms that focus on providing funding to local and national actors, including DI’s recently updated catalogue of quality funding practices. [15]

Grand Bargain signatories must:

- Urgently convene a frank and realistic political discussion with commitments to concrete pathways to increase direct funding (e.g. due diligence passporting) or indirect funding (e.g. pooled funds, locally led networked models) to local and national actors. This is required to focus efforts that can accelerate progress towards the 25% funding target to local and national actors by 2026.

- Implement the endorsed Collective Monitoring and Accountability Framework [16] to properly report and publish on indirect funding to partners, and ensure transparency on financing flows and accountability towards the 25% target.

- Continue to implement the IASC Guidance on the Provision of Overheads to Local and National Partners, [17] by developing and implementing institutional policies and working towards greater collaboration with local and national actors.

Insight

Helping local and national NGOs access quality financing

Elise Baudot Queguiner is Head of Humanitarian Financing at the International Council for Voluntary Agencies (ICVA). She has long experience in the humanitarian sector, including as General Counsel and Director of Policy, Strategy and Knowledge for the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and as an entrepreneur and consultant specialising in strengthening not-for-profit organisations.

Two of ICVA's core priorities are ensuring that 1) humanitarian financing meets the needs of populations affected by crisis and 2) NGOs have access to quality and principled funding. [18] Critical to these objectives is increasing funding to frontline local and national NGOs. This chapter highlights that local and national actors, which includes local and national NGOs, only received 0.6% of direct funding from Grand Bargain signatories in 2023.

Drawing from the expertise and operational experiences of our more than 160 members, and working closely with our Humanitarian Financing Working Group, ICVA takes a three-fold approach to funding frontline responders: 1) increase amounts of financing, 2) support access to quality funding and 3) ensure transparency of funding.

1) Increasing amounts of financing

While supporting efforts to increase efficiencies in the system, growing humanitarian needs cannot be met by current or declining levels of bilateral aid . While continually calling for increased bilateral funding, we are working with our members to explore new sources of financing, including building bridges to climate and development financing, accessing non-traditional donors and promoting innovative financing solutions.

2) Supporting access to quality funding

In addition to growing levels of financing, it is critical that local and national NGO responders can access quality funding. Strengthening organisation capacities and promoting equitable partnerships and intermediary funding mechanisms are key.

Informed by its localisation baseline work, ICVA is helping NGO forums in crisis contexts to foster peer learning and build shared services among their members, strengthening both institutional capacities and access to funding. Partnerships – whether between or among UN agencies and NGOs – are all challenged to reflect the Principles of Partnership. [19] ICVA works to address power imbalances, promote mutual understanding and develop solutions among our members and their partners. Together with organisations such as UNICEF [20] and UNHCR, partner contracts and systems have been improved. A community of practice on due diligence reform across all actors in the sector is being launched to further drive efficiencies.

Humanitarian pooled funds are a confirmed means to finance local and national NGOs. These funds have a wealth of experience and track record of innovation. We look forward to sharing insights among funds through a community of practice of pooled funds being launched with the Start Network. We are also increasing our evidence base on funds, exploring risk management dynamics among donors, pooled funds, international, national and local NGOs. We are also proud to host the CBPF Resource Facility [21] empowering local and national NGO voices in the governance mechanism of the CBPFs.

3) Ensuring transparency of funding

As this chapter highlights, despite progress, we still do not have effective means to truly measure funding being provided directly – or as directly as possible – to local and national NGOs. There are gaps in reporting by international actors. For pooled funds only the financial data of CERF and CBPFs is reported on. We have therefore partnered with DI to review these reporting challenges, test the feasibility of wider-scale reporting by local and national NGOs, and promote aggregate financial indicators among humanitarian pooled funds.

ICVA has been actively engaged in the Grand Bargain since its inception, playing a pivotal role in driving its commitments and advocating for more effective humanitarian action through improved partnerships, increased funding for local and national NGOs and greater transparency. Given current funding dynamics, we hope this process leads to a meaningful solution, addressing what is undoubtedly a significant and complex issue. However, without bold, transformative actions, there is a risk that efforts could become focused on superficial changes rather than addressing the structural challenges at hand. We need grand solutions to a grand problem.

Downloads

Notes

-

1

The Grand Bargain and Development Initiatives, 2023. Caucus on funding for localisation – Collective monitoring and accountability framework. Available at: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/grand-bargain-official-website/caucus-funding-localisation-collective-monitoring-and-accountability-frameworkReturn to source text

-

2

This figure differs from the percentage reported in the Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2023 due to updated methodology based on FTS carrying out a comprehensive classification/coding exercise of their entire recipient organisation database, according to Grand Bargain definitions.Return to source text

-

3

Although the Red Crescent Society of the UAE is usually classified as an intermediary or implementer, those contributions were reported to FTS as ‘new resources’ to the humanitarian system that were not already accounted for through other donor contributions and thereby are captured as direct funding in Figure 2.2.Return to source text

-

4

The Grand Bargain and Development Initiatives, 2023. Caucus on funding for localisation – Collective monitoring and accountability framework. Available at: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/grand-bargain-official-website/caucus-funding-localisation-collective-monitoring-and-accountability-frameworkReturn to source text

-

5

Granular data on UNHCR collaboration with funded partners with information on country, partner name, project title and budget is now available on the UN Partner Portal at: https://supportcso.unpartnerportal.org/hc/en-us/articles/13420656571671-Collaboration-with-Funded-PartnersReturn to source text