Falling short? Humanitarian funding and reform: Chapter 1

Global humanitarian assistance: Crisis and funding response

DownloadsSummary

In 2023, humanitarian response requirements were the highest on record. As of August 2024, the UN estimates that 311 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance. [1] This compares to the 168 million people in need less than five years ago. [2] [3] Most of the people are in contexts that have had ongoing responses from the international humanitarian community for years. Recent escalations or deteriorating conditions that put further strain on the system have come in contexts that have had response plans for a number of years, such as Lebanon, Palestine, Sudan or Ukraine.

At the same time, funding to the humanitarian sector stalled in 2023. Some donors have cut their humanitarian contributions, and private funding has come back down from the 2022 peak when it was buoyed by financing for the Ukraine response. Few government donors commit beyond 10% of the 0.7% official development assistance (ODA) target to humanitarian assistance. There are also signs that funding for international humanitarian assistance will reduce further in 2024, forcing humanitarian actors to make tough choices. Indeed, Development Initiatives’ (DI’s) projections show that total humanitarian funding, including that to interagency plans, is set to drop in 2024.

The path ahead for the humanitarian sector is not one of unprecedented growth, as it has been in recent years. Funding shortfalls, high humanitarian needs, difficulties in humanitarian access, and the protractedness of crises pose significant difficulties. The future is more uncertain.

What is the funding trend for international humanitarian assistance?

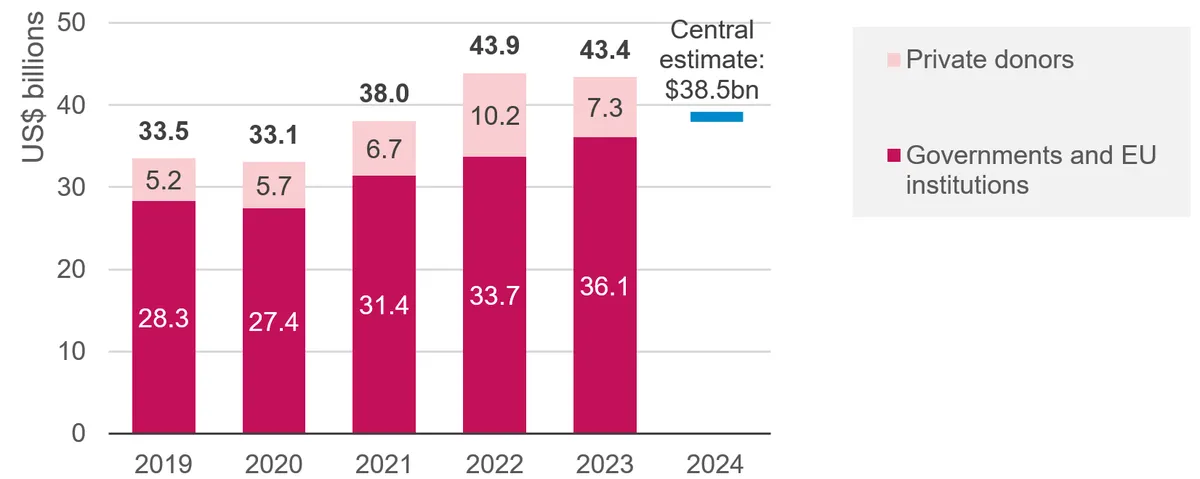

Figure 1.1: Humanitarian financing declined in 2023 and is projected to drop further in 2024

Total international humanitarian assistance, 2019–2023; projection for 2024

to come

Source: Development Initiatives (DI) based on Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC), UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Financial Tracking Service (FTS), UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) and our unique dataset for private contributions. Projection produced by DI.

Notes: Figures for 2023 are preliminary. Totals for previous years differ from those reported in previous Global Humanitarian Assistance reports due to updated deflators and data. Data is in constant 2022 prices. The 2024 projection is based on how much funding has been received at the time of writing compared to the same point in previous years (see our ‘Methodology and definitions’, Chapter 5).

Total international humanitarian assistance declined slightly in 2023 although the sector is still receiving historically high amounts of funding. The Ukraine crisis boosted humanitarian financing volumes in 2022, and while the rate of increase in humanitarian funding was not sustained, the sector received a similar amount of funding in 2023. [4] [5]

The outlook for the future remains uncertain. With key donors making cuts to their humanitarian budgets, and organisations across the sector reacting to the financial ‘crunch’ by reducing their budgets, funding levels for 2024 are projected to drop further. The central estimate of our 2024 projection is lower than the amount received in the previous two years. If realised, this would be the biggest reduction in total international humanitarian assistance on record.

- Preliminary data shows that in 2023, total international humanitarian assistance amounted to US$43.4 billion, a 1.1% decrease on 2022. This stagnation follows two years of significant growth in the sector as financing increased from US$33.1 billion in 2020 to US$43.9 billion in 2022.

Unlike previous years when resources increased from both public and private sources, 2023 is a more complicated picture. Government funding increased, though with large variability across donors (see the next sub-section).

- Funding from governments and EU institutions increased by US$2.4 billion in 2023. This means that, in 2023, public humanitarian assistance stood at its highest-ever level: US$36.1 billion.

- However, this top-line figure hides a more complex picture. While some key donors, such as the US, increased funding and thus drove the overall increase in public humanitarian assistance, other key donors cut humanitarian funding in 2023 (see the next sub-section). [6]

Funding from private donors declined significantly in 2023 following a short-lived increase driven by donations for the Ukraine response and has now reverted to a similar range as that seen before 2022.

- Private donors, such as the general public, foundations and corporations, contributed an estimated US$7.3 billion in 2023. This is a 28% decrease on 2022 levels which were US$10.2 billion.

- This reflects the waning ‘Ukraine effect’ on private humanitarian financing. In 2022, the sector saw a significant rise in private financing due to the escalation of conflict in Ukraine that year, but it appears that this has reverted back to previous private funding levels despite the continued war in Ukraine.

- Taking a longer-term view, the amount of funding from private donors is still trending upwards, with an average annual growth rate of 9.3% per year between 2019 and 2023.

Humanitarian assistance in 2024 seems set to fall by the biggest drop on record according to a projection produced by DI.

- The central estimate of the 2024 projection suggests that the sector is set to receive less funding than the previous year for the second consecutive year in 2024. This estimate, US$38.5 billion, would be a 11% decrease on 2023 levels at the same time that 311 million people need humanitarian assistance.

- The financing crunch has also led humanitarian actors to prioritise where they provide humanitarian assistance (the percentage of people in need who are targeted fell to 60% in 2024 – the lowest ever percentage targeted). [7] One stark example came when the World Food Programme warned that funding shortfalls in 2023 led to cuts in more than half of its operations worldwide, widely impacting the food security and nutrition of affected populations. [8]

- This finding aligns with the broader conversation across the sector about the financing crunch. Humanitarian agencies are undergoing staffing cuts, with both the International Rescue Committee and Save the Children reporting plans to reduce staff numbers. [9] [10]

- Our projection provides an indicative view of what might happen if funding trends from previous years repeat. Like any other projection, it is based on assumptions and comes with a margin of error. In 95% of simulations, the projection was between US$36.2 billion and US$41.9 billion. It is also based on how much funding has been received so far in 2024 compared to the same point in previous years. This method assumes that the pace of humanitarian funding contributions for the remainder of the year will match that of previous years. The projection also does not account for possible escalations in existing crises that might release greater funding amounts from donors (see our ‘Methodology and definitions’, Chapter 5 ).

What are the trends in donor contributions?

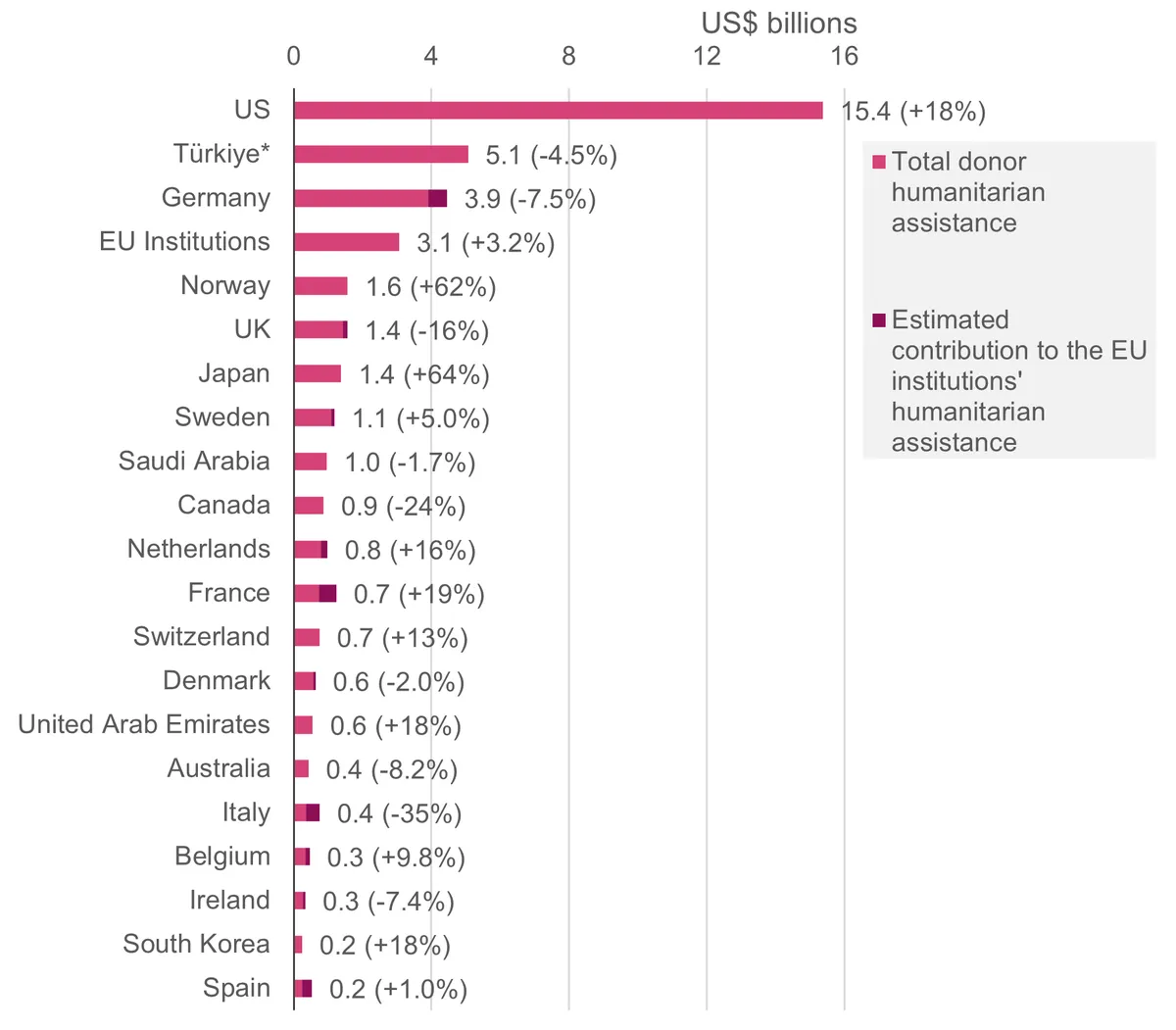

Figure 1.2: While most donors increased contributions in 2022, 2023 is a mixed picture

20 largest public donors of humanitarian assistance in 2023, and change from 2022

to come

Source: DI based on OECD DAC, UN OCHA FTS and UN CERF.

Notes: 2023 data is preliminary. Data is in constant 2022 prices. The total donor funding label reflects funding in 2023 and the percentage change compared to 2022 (excluding any estimated contribution through EU institutions). ‘Public donors’ refers to governments and EU institutions. Contributions of current and former EU member states to EU institutions international humanitarian assistance shown separately. Percentage change excludes EU contributions. *Türkiye is shaded differently because the humanitarian assistance it voluntarily reports to the DAC is largely spent on hosting Syrian refugees in Türkiye, and so not strictly comparable with the international humanitarian assistance from other donors in this figure. 2022 figures differ from the Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2023 due to final reported international humanitarian assistance data and a different year for constant prices.

In 2023, only 12 of the top 20 donors increased their humanitarian funding and 8 shrunk their humanitarian portfolios. To compare with the previous year, 15 of the top 20 donors increased their international humanitarian assistance in 2022. This could indicate that the tide is starting to turn: while not all donors are decreasing spending, it could be indicative of future trends.

- The largest increases in humanitarian assistance are from: the US (up US$2.4 billion, around an 18% increase), Norway (up US$0.6 billion, around a 62% increase), and Japan (up US$0.5 billion, around a 64% increase). The Netherlands, France, Switzerland, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the Republic of Korea all increased their humanitarian contributions by over 10%.

- However, some of the decreases came from large donors. Funding from Germany declined by 7.5%, from the UK by 16% and from Canada by 24% (each funding drop equal to around US$0.3 billion).

- Media reports suggest that there are poor prospects for the volume of humanitarian financing in 2024 and onwards. Following cuts to German humanitarian spending in 2024, recent reports suggest that this could be slashed by more than 50% in 2025. [11]

- Elsewhere, a report on the 2025 government budget of the Netherlands indicates that humanitarian financing may be cut by 9%. Meanwhile, UK ODA as a percentage of GNI fell to 0.36% in 2024, its lowest level since 2007 (excluding in-country refugee costs). [12] [13]

However, despite the decrease in funding from some of the top 10 donors of humanitarian assistance, overall public international humanitarian assistance increased in 2023, largely due to the data suggesting an increase from the US.

- Preliminary data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) suggests that US disbursements increased to US$15.4 billion in 2023, a large rise from US$13.0 billion in 2022. Yet, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)’s Financial Tracking Service (FTS) shows that US funding decreased from US$17.3 billion in 2022 to US$13.5 billion in 2023.

- While the DAC data represents disbursements, FTS data looks at both commitments and disbursements. Therefore, it appears that some portion of the 2022 US commitments were disbursed in 2023. [14]

The donor base continued to narrow in 2023, with only a small number of donors accounting for the vast majority of funding.

- The top 3 donors contributed 63% of public funding in 2023 (up from 61% in 2022), while the top 10 donors provided 85% of public funding (up from 83% in 2022). The top 20 donors accounted for 98% of all public funding, up from 95% in 2022.

In 2023, the EU established a voluntary target for humanitarian funding of 0.07% of GNI, and encouraged Member States to “continue efforts to close the humanitarian funding gap … and ensure that an appropriate share, for example 10%, of their ODA is devoted to humanitarian action, on the basis of existing humanitarian needs.” [15] [16]

- However, only a small number of donors contribute over 10% of the 0.7% ODA target as humanitarian assistance (that is, 0.07% of GNI).

- In addition to the unique case of Türkiye, [17] eight donors contributed over 0.07% of GNI: Norway (0.25% of GNI), Sweden (0.18%), Denmark (0.14%), UAE (0.11%), Germany (0.10%), Switzerland (0.09%), Saudi Arabia (0.09%) and the Netherlands (0.08%).

Was humanitarian funding sufficient?

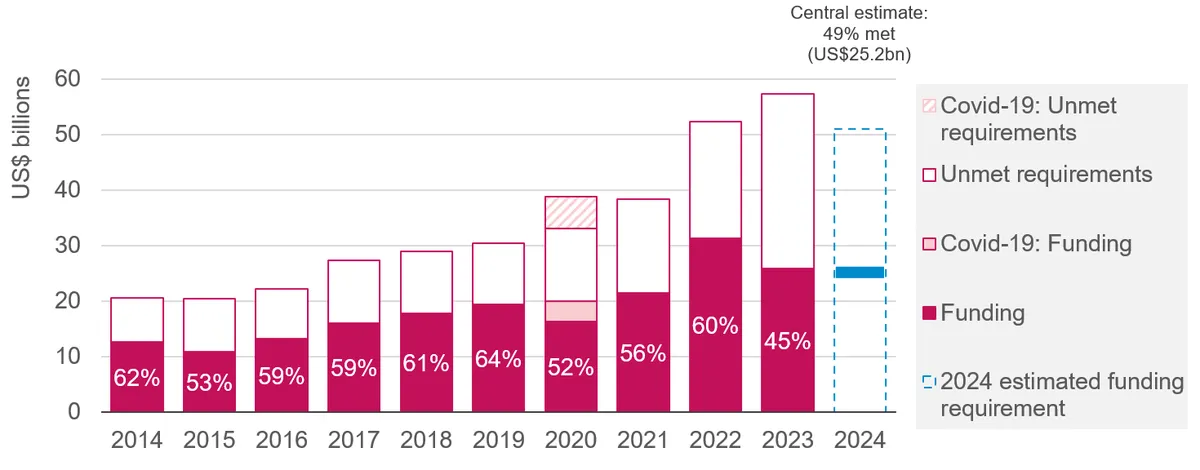

Figure 1.3: Rising funding requirements and a drop in funding to response plans have led to the widest funding gap on record

Funding and unmet requirements, UN-coordinated appeals, 2014–2023; projection for 2024

to come

Source: DI based on UN OCHA FTS, data extracted 19 July 2024 – 2024 funding requirements data updated on 2 October 2024; UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), data extracted 5 August 2024; and Syria 3RP financial dashboard data, data extracted 5 August 2024.

Notes: Data is in current prices. 2024 data is preliminary in terms of total requirements as of October 2024. Figures for the breakdown of funding to date in 2024 are not visualised because the funding data is partial and continuously changing at the time of writing. The 2024 projection is based on how much funding has been received so far in 2024 compared to the same point in previous years. The percentage of requirements met in 2020 includes all funding, for Covid-19 and other responses, against all requirements that year.

Over the past decade, the funding needed for humanitarian plans has grown significantly. Although funding towards these plans has also grown, it has struggled to keep pace with accelerating humanitarian needs. Interagency humanitarian plans were only 45% funded in 2023. This is the lowest percentage on record and has prompted interagency response plans in 2024 to narrow their focus and prioritise the use of more limited resources. According to our projection, funding is set to fall further in 2024.

- The global funding requirement in 2023 increased to US$57.3 billion, a US$5.0 billion increase from 2022.

- At the same time, funding to interagency humanitarian appeals dropped significantly from a peak in 2022 of US$31.3 billion (driven in part by the well-funded Ukraine crisis response) to US$25.9 billion in 2023 (a drop of 17%). This US$5 billion drop represents the largest year-on-year reduction in funding to UN-coordinated response plans on record.

- The combination of reduced funding and increased requirements in 2023 led to the lowest coverage on record at 45%. This is in stark contrast to the rest of the previous decade. From 2014 to 2022, plans were on average 59% funded in a given year.

- The funding gap increased to US$31.5 billion in 2023. This is a substantial increase from US$16.9 billion in 2021 and a significant departure from the historical precedent. Between 2014 and 2019, the humanitarian funding gap stood at an average of US$10.1 billion – already a huge number.

- The increase to US$ 31.5 billion in 2023 poses significant questions about the sustainability of the humanitarian system and its ability to meet the needs of people affected by crisis.

People affected do not live in an abstract world of ‘percentage of the funding requirement met’. International humanitarian assistance had its largest ever funding gap in real terms in 2023, meaning millions of people who needed assistance did not receive it.

- UN OCHA’s Global Humanitarian Overview mid-year update noted that underfunding had led to around 3.5 million Afghans “[losing] access to their yearly wheat consumption, including 50,000 female-headed households“, while more than 100 million targeted people worldwide had not received water, sanitation and hygiene assistance due to underfunding and attacks on infrastructure. [18]

- UN OCHA’s update points to other examples such as Myanmar where “health partners have had to prioritise services for internally displaced people, leaving about 1 million non-displaced people who had been targeted for support without assistance.”

- Another example comes from Yemen where UNHCR’s funding shortfall has led to the agency reducing its cash assistance by 25% in 2024. [19]

The amount of funding required in 2024 has declined from a record high in 2023, but this reduction is not solely due to a decrease in humanitarian needs.

- A joint statement from international NGOs notes that the number of people in need declined by 64 million people, in part reflecting efforts in some contexts to improve food security and nutrition. [20]

- However, the statement notes that it is also “a result of ‘boundary setting’ prioritisation that will effectively provide aid to some while denying it to others”. Meanwhile another analysis suggests that changes to targeting fewer people significantly decreased the funding requirement in 2024 and outweighed the effects of any change in the number of people in need. [21]

- Therefore, while less funding was ‘required’ in 2024, this is partly due to the humanitarian system prioritising what should be included in the ‘requirement’ number. As European Commissioner for Crisis Management, Janez Lenarčič, noted at the launch of the 2024 Global Humanitarian Overview , “These figures are more a result of prioritisation and a sharpening of focus on the most vulnerable.” [22]

DI’s projection for 2024 shows that interagency plans are set to receive even less than they did in 2023.

- Our central estimate is that interagency plans will receive US$25.1 billion in 2024. If this is the case, it will be the second year in a row that funding to humanitarian appeals has declined.

- Based on simulations of funding in 2024, humanitarian plans are likely to receive at least US$23.1 billion; while more than was received in 2021, this is unlikely to surpass US$29.7 billion and reach 2022 levels.

- If the central estimate of US$25.1 billion is realised, this would equate to 49% of the estimated total funding requirement. This would be only a modest improvement despite efforts by actors involved in coordinating the 2024 planning process to prioritise and more narrowly target people in need.

- Our projection provides an indicative view of what might happen if assumptions from previous years hold true. This projection, like any other, is based on assumptions and comes with a margin of error. It is based on how much funding has been received so far in 2024 compared to the same point in previous years. This method assumes that the pace of humanitarian funding contributions for the remainder of the year matches that in previous years. The projection also does not account for possible escalations in existing crises that might release greater funding amounts from donors.

Are protracted crises now the norm?

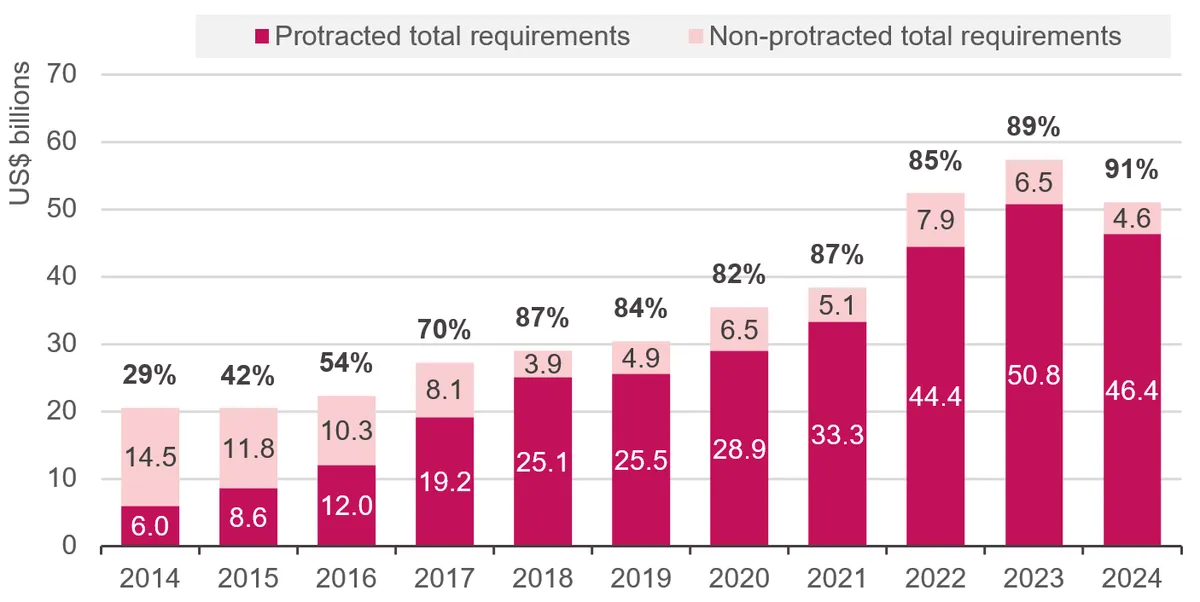

Figure 1.4: Over 9 in 10 dollars needed for interagency appeals are for protracted crisis responses

Funding and unmet requirements, UN-coordinated appeals, 2014–2024

to come

Source: DI based on UN OCHA FTS, UNHCR and Syria 3RP financial dashboard data.

Notes: Data is in current prices. 2024 data is preliminary in terms of total requirements as of October 2024. Protracted crises are defined as appeals which have had UN-coordinated interagency plans for at least five consecutive years, excluding COVID-19 response plans. Acknowledgement: chart is adapted from Humanitarian Funding Forecast (Lilly D and Pearson M), 2022. Why does the humanitarian system need so much money? Available at: https://humanitarianfundingforecast.org/stories-humanitarian-growth

A significant driver of the recent growth in funding required is that to protracted crises. DI defines protracted crises as contexts that have had UN-coordinated country response plans or regional response plans for at least five consecutive years.

In 2014, most funding required was for contexts that were not protracted. However, in 2024, the vast majority of funding required and provided was for protracted crisis responses, here defined as contexts with five or more years of consecutive UN-coordinated interagency plans.

- 91% of all funding required for interagency appeals in 2024 was to protracted crises, compared to only 29% in 2014.

- The amount of funding required for interagency appeals that are defined as not protracted fell from US$14.5 billion to US$4.6 billion.

- In 2014, there were nine appeals for protracted crises; in 2024, this rose to 31.

- The growth in funding needed for protracted crises is a significant driver of the growing funding gap with over double needed in 2024 compared to 2017.

The protracted nature of crisis requires a forward-looking approach to interagency coordination and planning. It should also spur increased links across the humanitarian–development–peace nexus to address the underlying drivers of crises. Multi-year funding and multi-year planning have never been more suited as ways to respond efficiently and effectively to humanitarian crisis, given that most continue year after year.

- Of 20 Grand Bargain donors, 14 report providing over 30% of their total humanitarian funding as multi-year funding in 2023 (according to available data from Grand Bargain self-reports).

-

The six donors who did not meet the target included:

- The EU/DG ECHO who report providing 13% of their funding as multi-year in 2023 (an increase from 7% in 2021).

- The US who report providing 22% of funding as multi-year in 2023, although in absolute terms it is a large increase from US$1.1 billion to US$2.9 billion.

- The UK and Japan are unable to report multi-year funding.

Public reporting on multi-year humanitarian funding outside these global aggregate figures from self-reports continues to be poor. This means that it is still not possible to identify which protracted crises or implementing organisations are receiving multi-year funding from Grand Bargain donors.

From rapid rise to a rocky road ahead: Conclusion

International humanitarian assistance has grown significantly over the last decade. Our analysis shows that it was as recently as 2012 that total ‘public’ international humanitarian assistance was under US$13.2 billion. The rise to nearly US$36.1 billion in 2023 is quite spectacular when seen in this context.

But the future is more uncertain. Humanitarian needs are far higher than they were a decade ago, and the acceleration of funding required outpaces the funding received. The humanitarian sphere now faces significant challenges that could slow this unprecedented growth.

Firstly, total humanitarian funding dipped in 2023 and is projected to do the same in 2024. Humanitarian organisations are reporting financial squeezes and staffing cuts. Humanitarian financing is below the level at the same point in 2023, and this feeds into a more sombre outlook. The key question is whether the signs in the data and reports across the sector are a temporary dip in the long-term trajectory of growth, or usher in a humanitarian recession.

Secondly, reductions in financing from a number of donors together with increased funding from the US have narrowed the donor base further. In turn, this has increased the system’s dependence on a shrinking number of key donors. This raises questions about the resilience of the humanitarian system in the face of unknown future political conditions.

Thirdly, interagency appeals now suffer from a US$31.5 billion funding gap. Despite donor funding continuing to increase, it is not keeping up with the demands of humanitarians. This means the humanitarian sector has a choice: do less (and prioritise between needs), reduce costs (and find efficiencies in the system) or find more money (from existing or new donors). These choices are difficult, and individual organisations and the wider system are finding ways to navigate a path through them.

However, beyond these short-term options is the reality that the humanitarian sector now operates as a large global safety net for people affected by crisis over the medium to long term. In 2024, 91% of appeal requirements are for protracted crises. And while the large funding gap is in part due to financing, it is as much due to a lack of political solutions. The inability of actors to tackle the root causes of conflict and complex emergencies means that humanitarian needs persist year after year, and as a result, the system keeps demanding more and more funding.

Downloads

Notes

-

1

UN OCHA, 2024. Global Humanitarian Overview 2024, August Update. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/global-humanitarian-overview-2024-august-update-snapshot-31-august-2024Return to source text

-

2

UN OCHA, 2019. Global Humanitarian Overview 2020. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/global-humanitarian-overview-2020-enarfrzhReturn to source text

-

3

The ‘People in Need’ (PIN) numbers referred to are taken from the UN OCHA’s Global Humanitarian Overviews. In previous ‘Global Humanitarian Assistance’ reports, the PIN has been calculated using different sources, and so is not directly comparable with the numbers used in the summary of this report.Return to source text

-

4

It should be noted that total volumes in 2022 and 2023 may appear differently in the response plans data due to how commitments were disbursed over these two years.Return to source text

-

5

OECD DAC Preliminary data shows that overall international financial assistance to Ukraine rose in 2023. While part of this assistance came in the form of budget support or other forms of ODA to the national government, it is not possible to quantify how much of this ODA that went to the national government was spent to address humanitarian needs in the country.Return to source text