Falling short? Humanitarian funding and reform: Chapter 4

Pre-arranged finance for anticipatory action

DownloadsSummary

Anticipatory action (AA) holds great promise as a more efficient and effective way to mitigate and respond to humanitarian impacts from predictable hazards. Grand Bargain signatories set out to prioritise the scale up of anticipatory responses through a caucus in 2024. Our analysis of data from the Anticipation Hub shows that this is much overdue, with less than 1% of international humanitarian assistance allocated to budgets for AA frameworks in 2023. For reference, previous research identified that around 20% of humanitarian responses between 2014 and 2017 addressed needs resulting from crises that could have been anticipated. [1]

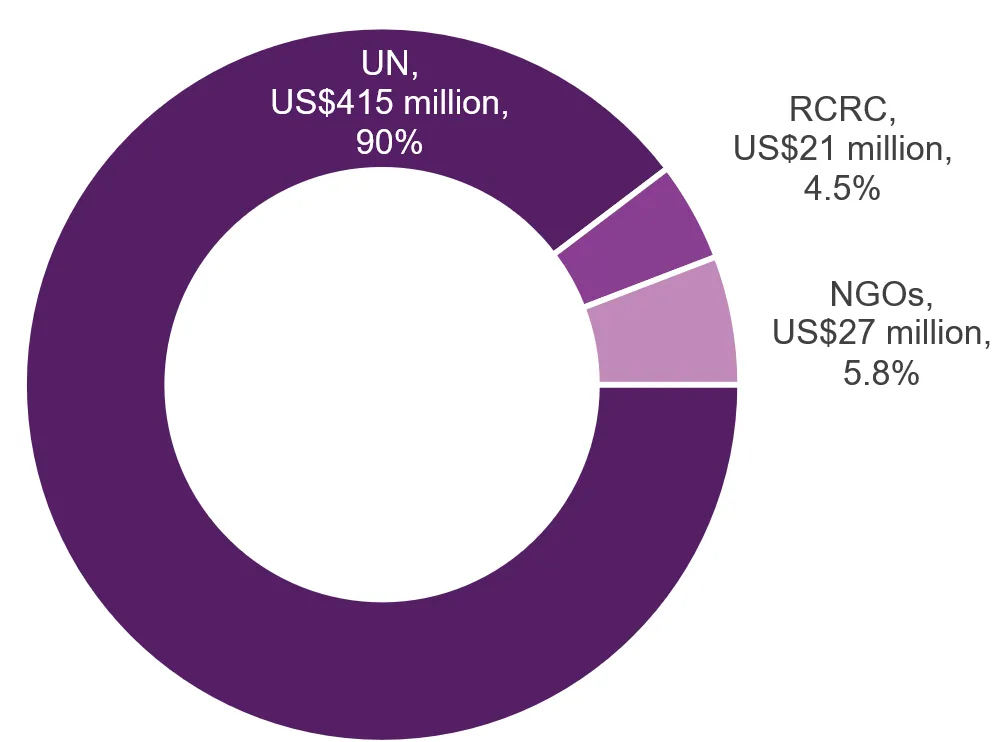

According to available data, 90% of funding to active AA frameworks was coordinated by UN agencies, with NGOs and the International Red Cross and Red Crescent (RCRC) Movement making up around 5% each. This is primarily because the budgets of frameworks coordinated by the UN are over 10 times as large on average as those of NGOs and the RCRC Movement. Based on limited data, local and national actors participated in less than half the active AA frameworks, which made up around an eighth of total ‘fuel’ funding, and mostly as implementing partners.

Research from the Centre for Disaster Protection has further shown that AA is just one modality in the bigger toolkit to pre-arrange finance for crisis responses. Humanitarian actors must be conscious of all forms of pre-arranged crisis finance and advocate with providers, especially multilateral development banks, to leverage them for building an enabling environment for disaster risk management and ensure complimentary coverage, focusing on the most vulnerable populations at the highest risk of hazards.

By 'pre-arranged finance' we mean funding that is committed before a humanitarian disaster or crisis occurs. This can take the form of contingent credit, risk transfer schemes (e.g. insurance), contingency budgets or other instruments. The funding is disbursed when a predetermined trigger is met (for example, a certain forecast or event) and for a predetermined purpose relating to the crisis response or management (for example, a contingency plan consisting of specific, pre-defined activities or general budget support).

Funding for 'Anticipatory action' is one form of pre-arranged finance. By it, we mean activities that are implemented immediately before a predicted hazard occurs, or before its most severe consequences unfold, to diminish its possible humanitarian impacts. ‘Fuel’ funding for the implementation of these activities once AA frameworks become activated is committed before the disaster event. ‘Build’ funding refers to investments that directly set up or strengthen the operation of anticipatory action frameworks. The decision to act is then taken based on a pre-agreed trigger, usually in the form of a forecast of when, where and how the hazard will occur. AA frameworks are set up by one or multiple organisations as the formal response mechanism to enable them to act in advance of predictable shocks by clarifying who will receive funding for what and based on which triggers. See our ‘Methodology and definitions’, Chapter 5 for more on how we calculate funding for AA.

How much funding was available to and disbursed by anticipatory action frameworks?

AA offers a more effective way of addressing the possible humanitarian impacts from predictable hazards by mitigating their consequences and pre-emptively addressing expected needs. It thereby protects lives, as well as people’s livelihoods and assets, and sustains development gains. Grand Bargain signatories clearly recognise the potential for AA and are working to scale it up through the first and so far only caucus, under its latest iteration. A group of signatories set out in February 2024 to reach agreement around: funding commitments to scale up AA, improved coordination mechanisms for AA frameworks, and a joint and transparent approach to tracking progress of this scale up. [2]

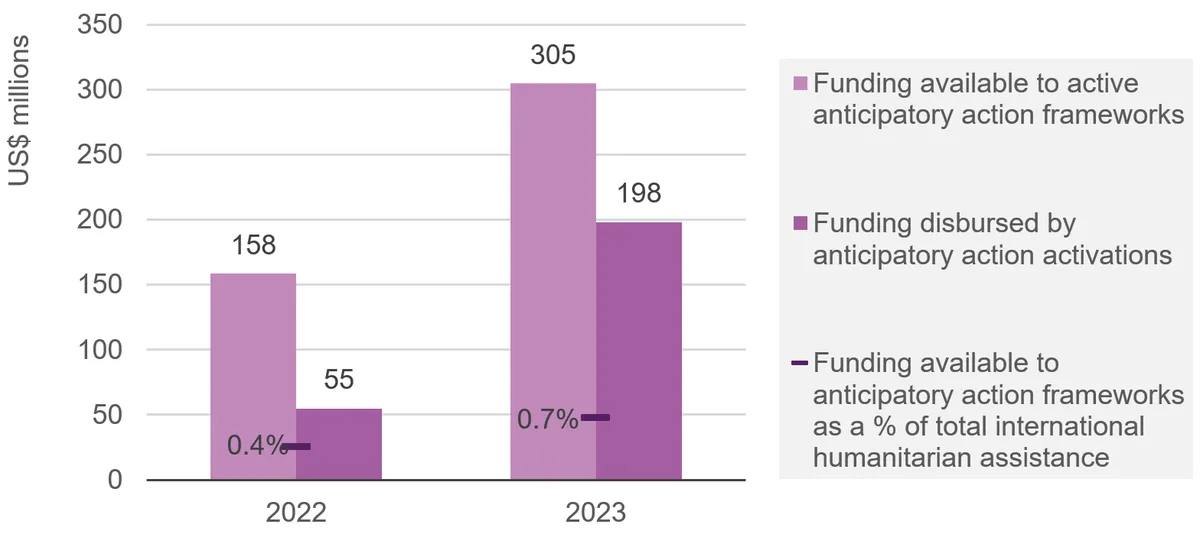

Figure 4.1: Funding available to anticipatory action frameworks increased in 2023 but still makes up less than 1% of total international humanitarian assistance

Total budget available for anticipatory action frameworks and disbursed through activations, 2022 and 2023

to come

Source: Development Initiatives (DI) based on Anticipation Hub data.

Notes: The Anticipation Hub’s data collection method differed in 2022 and 2023, meaning that part of the increase shown in this figure is due to a more expansive data collection. DI adapted the Anticipation Hub dataset by including missing activations in the active frameworks data for any given year (see our ‘Methodology and definitions’, Chapter 5).

According to our analysis of data compiled by the Anticipation Hub (see our ‘Methodology and definitions’, Chapter 5 ), the volume of ‘fuel’ funding – meaning funding that is available for activation of AA frameworks – available to those frameworks and disbursed by them based on pre-agreed triggers have both increased from 2022 to 2023. Still, the total volumes available to AA frameworks continue to make up less than 1% of total international humanitarian assistance. This is despite past research identifying that around a fifth of humanitarian response needs result from highly predictable shocks. [3]

- ‘Fuel’ funding available to active AA frameworks almost doubled from US$158 million in 2022 to US$305 million in 2023. Funding disbursed by activations of some of those frameworks increased almost four-fold over the same period, from US$55 million to US$198 million. While these increases are partly due to a more expansive data collection method by the Anticipation Hub in 2023 compared to the previous year, [4] they likely also reflect a real increase in funding available to AA frameworks.

- Despite this large increase, funding available to existing AA frameworks still made up less than 1% of total international humanitarian assistance in 2023 (0.7%), though this is almost twice the share of the previous year (0.4%). This low share continues to be far below the 20% of humanitarian response requirements that 2019 research identified to be highly predictable. [5]

- In 2023, the 166 existing AA frameworks primarily protected against droughts (58), followed by different types of floods (54) and different types of storms (28).

- The data compiled by the Anticipation Hub does not track which donors contributed to active frameworks. A small group of large humanitarian donors already affirmed their commitment to scale up AA in a G7 statement in 2022. [6] The German Federal Foreign Office (GFFO) was the only donor with a quantitative target for scaling up funding to AA at 5.0% of total humanitarian funding provided and managed to reach this in 2023. It is important that the AA Grand Bargain caucus outcome statement lays the foundation for comprehensive, comparable and transparent reporting by donors on their future investments in scaling up AA (see Box 4.1 on the challenges of transparency ).

Box 4.1

The challenges of public transparency for anticipatory action funding

Publicly available, comprehensive and granular data on AA funding and frameworks is a prerequisite for improved coordination and to enable accountability for scaling up AA funding efforts.

The most comprehensive public dataset on AA frameworks is maintained by the Anticipation Hub. [7] This contains information for active frameworks regarding the year, country, the hazards covered, coordinating organisation, implementing partners, available budget per activation (or ‘fuel’ funding) and other data. The corresponding dataset on AA framework activations is even more granular. However, this data needs to be manually collected by the Anticipation Hub and is only published annually. It also does not include funding data by donors to AA frameworks, which makes it difficult to hold donors to account for scaling up their investments into AA.

The Grand Bargain Caucus on Scaling up Anticipatory Action was established to agree a clear methodology and process for tracking this scale up. In 2024, the Centre for Disaster Protection convened a community of practice on pre-arranged financing data quality and transparency, involving experts from aid reporting platforms, donor governments, the UN, NGOs and research institutions. Building on discussions in this group, DI was tasked by the Centre for Disaster Protection to research improving the transparency of pre-arranged finance, which includes a broader set of financing instruments with pre-agreed triggers to respond to crises alongside AA (e.g. contingent credit, insurance schemes and contingency budgets). Some of the early lessons from this research, which build on each other, may be helpful in informing the approach to public transparency of funding for AA frameworks:

- A shared definition of what constitutes ‘fuel’ and ‘build’ funding for AA is essential to form a shared basis for comparable public reporting. The forthcoming AA caucus offers an opportunity to provide shared definitions for the wider sector to endorse.

- There needs to be sufficient political will for each signatory to incorporate those definitions in internal tracking systems so that data on funding for AA can be extracted for public reporting.

- Public targets for scale up, whether specific to individual signatories or shared across a group of signatories, have been shown to provide important levers for generating internal buy-in or facilitating external accountability efforts in the context of AA and other Grand Bargain commitment areas.

- Public reporting on AA funding should, as far as possible, be incorporated in other standard processes used by donors to report their funding, e.g. to the FTS and/or the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI). Once a shared definition is agreed and there is sufficient demand to track progress against it, it should be possible for both systems to incorporate standardised reporting fields to reflect funding for AA and thereby make the data more comparable and user-friendly to access. This would also minimise the burden of reporting through additional, parallel reporting processes.

These points refer to the ‘money-in’ for AA frameworks, i.e. the funding provided by donors. Other important dimensions of public data transparency are the ‘money-out’ of AA framework activations and greater detail on what hazards and geographies are covered by each framework. This level of data granularity is likely required to facilitate better coordination and collaboration across different AA initiatives. This detail goes beyond what can feasibly be incorporated into existing, interagency reporting platforms and therefore may need to be collected by the Anticipation Hub or others. However, incorporating unique project identifiers or other unique identifiers (e.g. IATI activity identifiers) into datasets of AA frameworks would open up possibilities to join this AA framework data with funding data from already existing aid reporting platforms.

Who coordinated or was involved in active anticipatory action frameworks?

Figure 4.2 Most funding available to active anticipatory action frameworks was coordinated by UN agencies, according to available data

Percentage and financial volumes of total activation budgets for active anticipatory action frameworks by coordinating organisation type, 2022 and 2023 combined

to come

Source: DI based on Anticipation Hub data.

Notes: Given the data collected by the Anticipation Hub is biased towards the Anticipatory Action Task Force, existing AA frameworks and activations from other actors, in particular locally led AA initiatives, might not be included in the underlying dataset. DI adapted the Anticipation Hub dataset by including missing activations in the active frameworks data for any given year (see our ‘Methodology and definitions’, Chapter 5).

According to data that we adapted from the Anticipation Hub, [8] most funding available to active AA frameworks was coordinated by UN agencies, with NGOs and the RCRC Movement making up around a twentieth each. This balance shifts when considering the number of AA frameworks coordinated by each of these three organisation types, which was more evenly distributed. Based on limited data, local and national actors participated in less than half of the active AA frameworks that made up around an eighth of total ‘fuel’ funding, and mostly as implementing partners.

- The share of ‘fuel’ funding within active AA frameworks coordinated by UN agencies was around 90% for 2022 and 2023 combined, with a similar share in both years (88% in 2022 and 91% in 2023). The RCRC Movement coordinated 4.5% of funding and NGOs 5.8%, according to available data.

- UN agencies coordinate such a large share of the financial volumes primarily because the AA frameworks they coordinate are on average more than 10 times the size in terms of funding (averaging US$4.0 million) of the AA frameworks coordinated by NGOs or the RCRC Movement, according to the dataset DI compiled based on Anticipation Hub data (see our ‘Methodology and definitions’, Chapter 5 ). The number of frameworks coordinated by each organisation type across 2022 and 2023 is more evenly split, with 113 for the UN, 76 for NGOs and 58 for the RCRC Movement.

- Data on local and national actors’ involvement in active AA frameworks is limited, partly because the Anticipation Hub’s data collection largely draws on initiatives involving members of the Anticipatory Action Task Force (the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, the Start Network, the World Food Programme, the Food and Agriculture Organization and UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)). [9] Locally led initiatives that do not involve task force members may therefore not be captured.

- Based on limited data, about an eighth (12%) of the total funding available to active anticipatory action frameworks in 2022 and 2023 involved local and national actors, though usually as one of multiple implementing partners. This share is stable across both years. It is therefore not possible to determine what share of funding disbursed by AA framework activations was implemented by local and national actors. Given that local and national actors usually participated in smaller-scale AA frameworks, their involvement by number is higher, at close to half (47% in 2022, 43% in 2023).

Increasing anticipatory action: Conclusion and recommendations

According to available data, the potential of AA to more effectively address humanitarian impacts compared to reactive responses remains underused despite the growing frequency and intensity of predictable hazards. Realising potential cost-efficiencies by anticipating humanitarian impacts before they fully unfold is especially important given the shrinking pot of international humanitarian funding (see Chapter 1 ). The political commitment to scale up funding for AA through the Grand Bargain caucus, ideally enshrined in a quantitative target, is much overdue. This is essential for the sector to save more lives and protect people’s livelihoods from predicable disasters.

As research from the Centre for Disaster Protection shows, [10] AA is just one modality in the toolkit for a more forward-looking and risk-based approach to disaster response. Other pre-arranged financing mechanisms such as contingent credit, risk transfer schemes (e.g. insurance) and contingency budgets make up a much greater financial volume than AA. Those other mechanisms tend to target middle- or high-income countries and almost three-quarters are provided by multilateral development banks. AA frameworks must be conscious of leveraging those investments to build an enabling environment for disaster risk management and target the populations most at risk of disasters in low-income countries that are not covered by other pre-arranged financing.

There should be greater efforts to support and make visible locally led AA initiatives, whether by governments or civil society. The AA policy agenda risks following the cash and voucher assistance commitment, which managed to increase funding through a supporting evidence base and sufficient political will, but concentrated this funding among international actors. To firmly embed anticipatory approaches as part of national disaster management strategies, domestic governments needs to be involved with or ultimately have ownership of AA frameworks wherever possible. Data and models that facilitate AA frameworks should also be made publicly available to facilitate learning and ensure accountability to the populations affected by the identified disaster risks. Without greater local leadership of AA frameworks, populations most at risk from disasters may remain furthest away from the critical decision making that affects them.

Policy recommendations:

- Grand Bargain donors should commit to increasing their funding for AA to at least 5.0% of their total humanitarian funding by 2026.

- AA donors and coordinating agencies should advocate with other providers of pre-arranged financing, including multilateral development banks, to build the enabling environment for disaster risk financing in countries that are most vulnerable to disasters and focus their own efforts and resources on immediate emergency responses.

Coordinating agencies of AA frameworks should share their underlying models and disaster risk data with local populations and governments, and involve national disaster management authorities wherever possible. There should also be more visibility and donor support for locally led AA frameworks.

Insight

Why quality and quantity both matter in funding anticipatory action

Lydia Poole is a research and policy specialist whose work focuses on the transformation of the international crisis response system. She is Associate Director for Policy and Evidence at the Centre for Disaster Protection, leading a programme of research on the transformative potential of disaster risk financing. Lydia’s previous research and policy work has focused on supporting the localisation movement and reform of the international crisis financing architecture, building on her experience in the humanitarian crisis contexts of coordinating responses with UN OCHA and managing NGO primary healthcare programmes.

Anticipatory action has the potential to deliver improved welfare outcomes for people at risk of crisis, [11] and to drive a shift towards a more risk-informed and timely crisis response model.

In 2021, G7 members committed to “significantly increase our financial support in anticipatory action programming” and “develop ways to better track and report on our humanitarian funding of anticipatory action”. [12] The Centre for Disaster Protection provided advice on tracking funding for anticipatory action, which was piloted by the UK and Germany, with an adapted version adopted by the GFFO.

At the collective level, funding for anticipatory action remains hard to track, in part because it is often funded through internal funding mechanisms and multi-activity programmes.

Based on the best available data, financing for anticipatory action grew in 2023, but remains a very small proportion of humanitarian financing overall. As shown by the Centre for Disaster Protection’s analysis [13] and affirmed by Figure 4.1 above, data collected by the Anticipation Hub indicates that funding available within anticipatory action frameworks and funds, and disbursed by them, increased between 2022 and 2023. This funding represents just below 1% of total humanitarian funding in 2023.

Research conducted by the Risk-informed Early Action Partnership (REAP) highlights a preference among donors for funding the setting up of new anticipatory action frameworks, the ‘build’ money, over the predictable financing needed to maintain financial readiness to respond, the ‘fuel’ money. [14] Research conducted by the Centre for Disaster Protection adds to this a shortage of financing for a wider set of investments needed to ensure preparedness, including funding to develop and maintain up-to-date vulnerability mapping and beneficiary registries, reliable early warning systems, pre-positioned supplies, and readiness plans and training. [15]

Therefore, in addition to tracking progress in funding for anticipatory action overall, it is also important to consider the quality of that funding including the balance of ‘build’ and ‘fuel’ funding and funding for the ‘enabling conditions’ that are necessary for rapid responses.

Downloads

Notes

-

1

Analyzing gaps in the humanitarian aid and disaster risk financing landscape, 2019. Weingärtner L and A Spencer. Available at: www.anticipation-hub.org/download/file-153Return to source text

-

2

The Grand Bargain, 2024. Grand Bargain political caucus to scale up anticipatory action: Problem definition and caucus strategy. Available at: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/grand-bargain-official-website/launch-caucus-scaling-anticipatory-action-0Return to source text

-

3

Analyzing gaps in the humanitarian aid and disaster risk financing landscape, 2019. Weingärtner L and A Spencer. Available at: www.anticipation-hub.org/download/file-153Return to source text

-

4

See Annex 1 in Anticipation Hub, 2024. Anticipatory Action in 2023: A Global Overview. Available at: www.anticipation-hub.org/advocate/anticipatory-action-overview-report/overview-report-2023Return to source text

-

5

Analyzing gaps in the humanitarian aid and disaster risk financing landscape, 2019. Weingärtner L and A Spencer. Available at: www.anticipation-hub.org/download/file-153Return to source text