FCDO’s aid spending for nutrition: 2020

Building on previous assessments, this report presents detailed information on the United Kingdom (UK) Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO)’s aid spending to improve nutrition, including assessing progress against its historic commitments.

DownloadsA note on the data in this paper:

This was report was updated in June 2024 to correct an error affecting the published value for FCDO’s total aid spending for nutrition as a proportion of its total ODA spending in 2020. This was originally reported as 8.5% for 2020. The correct value is 12.8%.

Submitted by DAI in association with

Executive summary

Malnutrition levels throughout the world remain at unacceptably high levels. Despite some progress the world is largely off-track for meeting global maternal, infant, and young child nutrition (MIYCN) targets. Estimates of the financial resources required to accelerate progress toward these targets are high and have even increased.

Official development assistance (ODA, also known as aid) for nutrition remains an essential resource in achieving short-, medium- and long-term outcomes in developing countries, though budgets face increasing pressures and demands from multiple fronts. The economic impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic have put especial pressure on ODA budgets worldwide, with recovery to pre-pandemic levels expected only towards the end of the decade. Nevertheless, sources of nutrition financing, including ODA, require sustaining and scaling up. This is well recognised, and new, additional financial commitments were sought at the 2021 Tokyo Nutrition for Growth (N4G) Summit, building on a legacy of prior commitments made at the 2013 London N4G Summit. The UK committed to integrate nutrition objectives across its programme portfolio (including in sectors such as health, humanitarian, women and girls, climate and economic development), to spend £1.5 billion on nutrition programmes between 2022 and 2030, and to adopt the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Nutrition Policy Marker at programme design stage.

Key findings

Against this backdrop, this report presents detailed information on the United Kingdom (UK) Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO)’s aid spending to improve nutrition, including assessing progress against its historic commitments. Building on previous assessments (Development Initiatives, 2014; 2015; 2016; 2017; 2018; 2019; 2020; 2021) and using the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Donor Network’s (SDN) agreed methodology, the report analyses the latest available data up to 2020, alongside historical data, and finds the following:

- The FCDO has disbursed over £5 billion (around US$6.8 billion) of nutrition ODA since 2013.

-

The FCDO has not quite met its nutrition-specific 2013 N4G commitment.

- The FCDO has cumulatively disbursed £530.2 million in nutrition-specific funding (excluding matched funding), just shy of its original N4G commitment of £574.8 million by around £44.7 million.

-

The FCDO has far exceeded its nutrition-sensitive 2013 N4G commitment and has spent more than double its original target.

- The FCDO has cumulatively disbursed £4.6 billion to nutrition-sensitive interventions since 2013, and so has exceeded its nutrition-sensitive target of £2.1 billion.

-

In 2020, FCDO’s total aid spending for nutrition increased for a second consecutive year to reach a record US$1.1 billion (around £855.6 million).

- Spending on nutrition-specific programmes decreased by a quarter, from US$156.5 million in 2018 to US$117.4 million in 2020; this is the lowest amount since 2015 and a result of the natural completion of some existing programmes and fewer disbursements to existing nutrition-specific programmes.

- Spending on nutrition-sensitive programmes increased for the second consecutive year, by 19.5%, from US$872.7 million in 2019 to US$979.5 million in 2020; this is higher than in any previous year and a result of increased spending to existing nutrition-sensitive programmes.

- Proportional to its total bilateral ODA spending, FCDO’s total nutrition spending increased to a peak 12.8%.

-

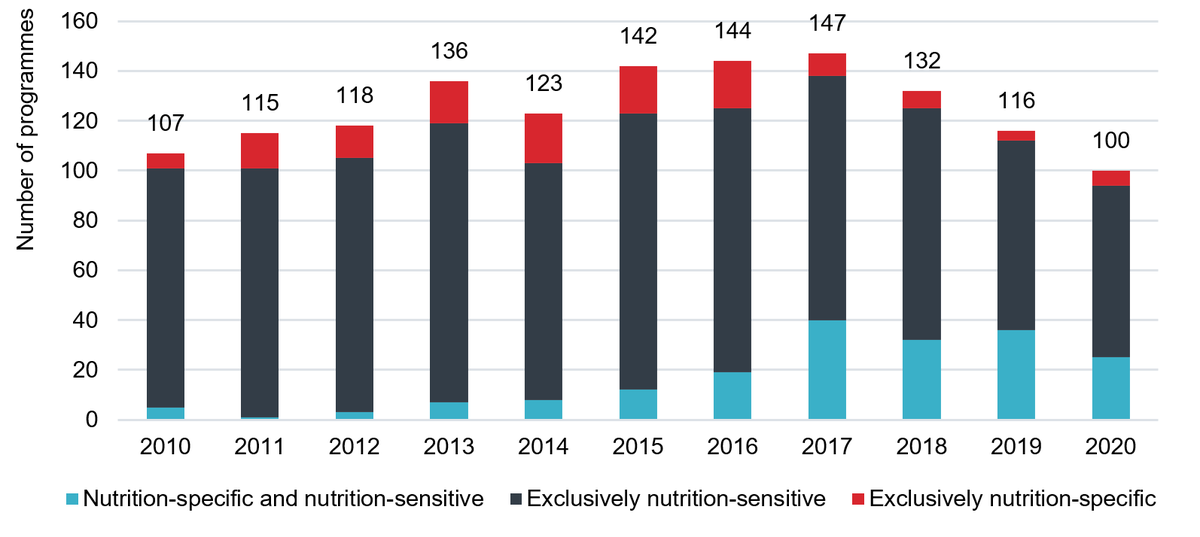

In 2020, FCDO supported 16 fewer programmes than 2019, though with greater disbursements.

- The total number of nutrition-related programmes supported by FCDO decreased for the second consecutive year, by 16 to 100 programmes, which is the fewest observed throughout the period 2013–2020

- This portfolio included six nutrition-specific programmes, 69 nutrition-sensitive programmes, and 25 programmes with both nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive components.

- The mean annual amount FCDO spent on a nutrition-related programme in 2020 was US$11.0 million.

-

Since 2013 FCDO’s nutrition-sensitive spending on humanitarian and health programmes has increased hugely.

- Over half of FCDO’s nutrition-sensitive spending is on humanitarian programmes, which reached a record US$577.1 million in 2020.

- Nutrition-sensitive spending on health programmes increased for a second consecutive year and represents 27.4% of FCDO’s total nutrition-sensitive spending in 2020.

- Spending also increased on education, governance and security, and WASH programmes.

- Nutrition-sensitive spending decreased in the agriculture and food security, social services, environment, business and industry, and infrastructure sectors.

-

Net spending increased to all regions except the Middle East.

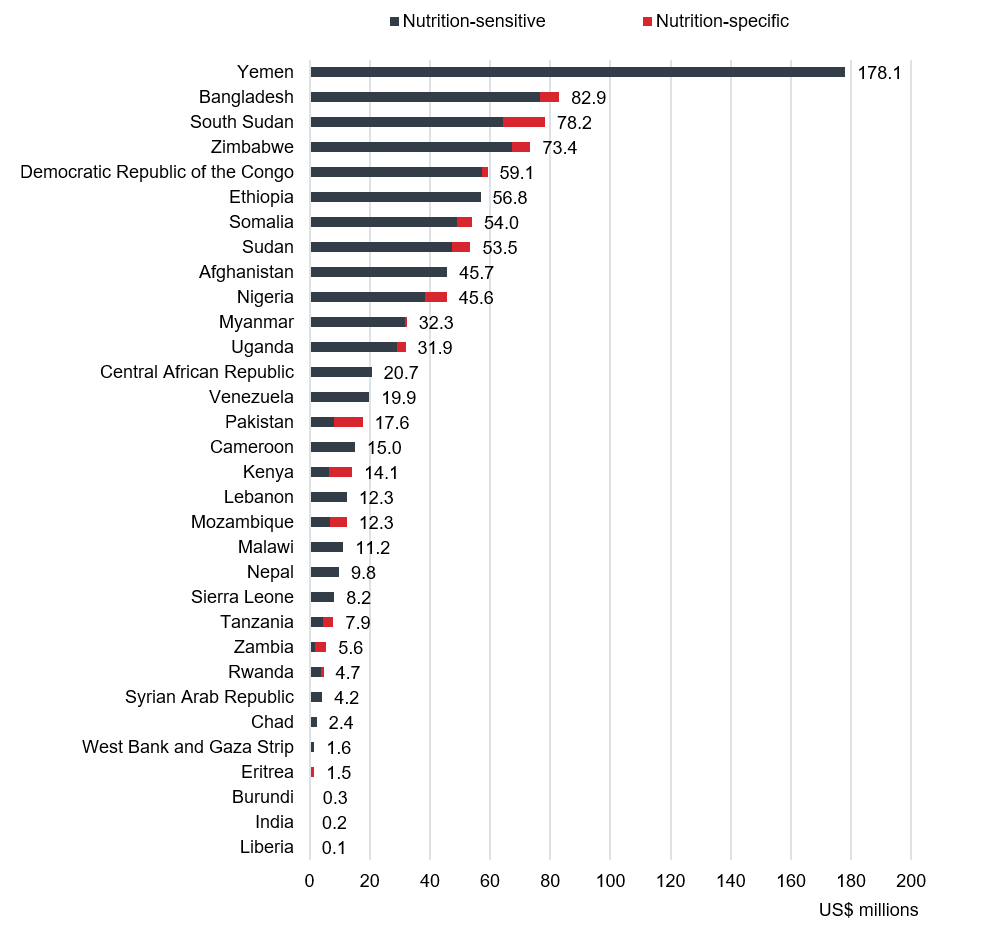

- While spending decreased, Yemen remains the greatest single country recipient of FCDO’s nutrition ODA in 2020.

- Spending increased in 16 countries though decreased in another 20.

- The mean annual amount received by any country increased from US$24.7 million to 30.0 million in 2020.

- A record 79% of FCDO’s nutrition spending had gender policy objectives in 2020.

Introduction

The Department for International Development (DFID) merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) on 2 September 2020 to become the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). This document refers only to FCDO and covers commitments and disbursements made by DFID prior to the merger.

As part of continuing efforts to track and better understand donor financing for nutrition, this report identifies and analyses the UK FCDO’s official development assistance (ODA) spending on nutrition-related projects. The analysis uses the methodology developed by the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Donor Network (SDN) [1] with the aim of capturing such spending in order to better track resources for nutrition. This methodology is adopted here to capture FCDO’s nutrition spend in 2020 and for monitoring progress towards meeting the overall spending targets in the period 2013–2020, to which the UK committed at the 2013 Nutrition for Growth (N4G) Summit.

At the 2021 Tokyo Nutrition for Growth Summit (N4G), the UK pledged to spend £1.5 billion between 2022 and 2030 on: addressing the nutrition needs of mothers, babies and children, tackling malnutrition in humanitarian emergencies and making sure nutrition is central to the FCDO’s wider work over the next 8 years. It will focus on integrating nutrition objectives in its support to health and food systems, as well as working in fragile and conflict affected states to protect the most vulnerable as part of its implementation of the Ending Preventable Deaths approach. The UK also committed to adopting the OECD DAC Nutrition Policy Marker at programme design stage, to improve tracking and accountability for nutrition programmes. Progress against these new commitments will not be assessable until at least 2022. This report focuses only on prior commitments, covering the period for which there is available data, 2010–2020.

Previous iterations of this assessment and report covering the years 2010–2018 were produced for FCDO through the Maximising the Quality of Scaling Up Nutrition Plus (MQSUN+) programme.

Approach

As in previous years, this analysis uses the SDN methodology and data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Creditor Reporting System (CRS) database to identify nutrition-related programmes and calculate FCDO’s total nutrition-related spend. Data for 2020 were received on 27 January 2022.

The CRS database has two measures of ODA: commitments and disbursements. The former is a formal obligation to disburse funds and should not be confused with the N4G commitments; the latter is the funding that donors have actually provided. This report refers to the disbursements measure of FCDO’s ODA, representing their actual spending on nutrition each year expressed in US$.

The methodology is applied to FCDO’s bilateral ODA, capturing flows from FCDO to official bodies in recipient countries. It should be noted that this methodology does not capture FCDO’s financing to multilateral agencies through contributions to their core budgets, though it does capture where FCDO funded those agencies to implement specific programmes.

The applied methodology identifies two types of nutrition-related programmes: those that are ‘nutrition-specific’ and those classified as ‘nutrition-sensitive’ (see Appendix 1). In line with FCDO’s N4G commitments made in 2013, FCDO also provides details of their matched funding. These funds are tracked separately, as they constitute a separate category of FCDO’s N4G commitments, but they are included in the overall assessment of FCDO’s spending on nutrition. Full methodological details are given in Appendix 1.

This report includes an assessment of the latest progress against existing UK N4G commitments, an overview of FCDO’s nutrition spending, disaggregated as nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive, and a more detailed analysis of FCDO’s spending across sectors and recipient countries. It also includes a brief analysis of the gender sensitivity of FCDO’s nutrition spending using data also reported to the CRS database. Data on progress against existing UK N4G commitments is expressed in GBP to allow for direct comparison to their original wording. US$ are used elsewhere.

While FCDO is the largest source of UK ODA and the focus of this analysis, other UK government departments and agencies can also contribute to UK ODA, including for nutrition interventions. This is however comparatively limited. In 2020 for example, only the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills reported any ODA for nutrition-specific programmes, equal to around US$8.5 million. ODA to nutrition-sensitive interventions by other UK government agencies have not been assessed here.

Summary of FCDO’s 2013 N4G commitments

In 2013 at the first N4G Summit hosted in London, FCDO (then DFID) committed to triple its investment in nutrition-specific programmes, equal to spending a total of £574.8 million between 2013 and 2020 (hereby referred to as FCDO’s ‘nutrition-specific N4G commitment’).

FCDO also committed to match funding for new financial commitments for nutrition made by other actors, up to a value of £280.0 million (hereby referred to as FCDO’s ‘matched funding N4G commitment’). This matched funding approach was put in place to encourage other donors to commit funding on top of what was committed at the N4G Summit. FCDO uses this to support the scale-up of other nutrition-specific interventions, making it an important part of the spend on nutrition.

Finally, FCDO also committed to increase its nutrition-sensitive spending by eight percentage points over the same period, equal to spending a total of £2.1 billion by 2020 (hereby referred to as FCDO’s ‘nutrition-sensitive N4G commitment’).

These commitments and progress toward them are detailed in the following sections.

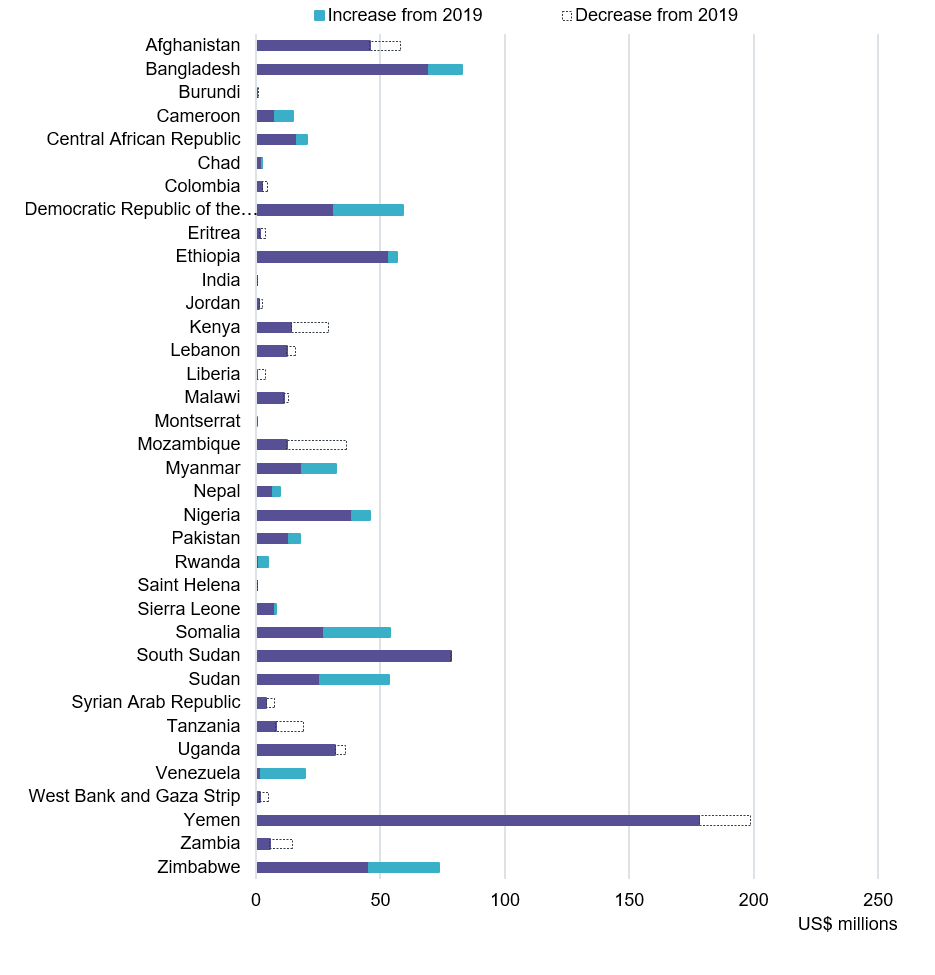

In 2020, the FCDO made nutrition-specific disbursements of £54.7 million (excluding matched funding) and nutrition-sensitive disbursements of £764.0 million, as well as £36.9 million of nutrition-specific matched funding disbursements (Figure 1). Cumulatively, this amounts to £5.3 billion spent since 2013.

Figure 1: The FCDO has disbursed over £5 billion of nutrition ODA since 2013

The FCDO’s cumulative nutrition-specific, nutrition-sensitive and matched funding ODA disbursements for 2013–2020

Line graph showing the FCDO’s cumulative nutrition-specific, nutrition-sensitive and matched funding ODA disbursements for 2013–2020

Notes: Nutrition-specific totals exclude matched funding. Disbursements are presented in 2020 prices.

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on DAC CRS data, FCDO data, and OECD National Accounts Statistics: purchasing power parities (PPPs) and exchange rates.

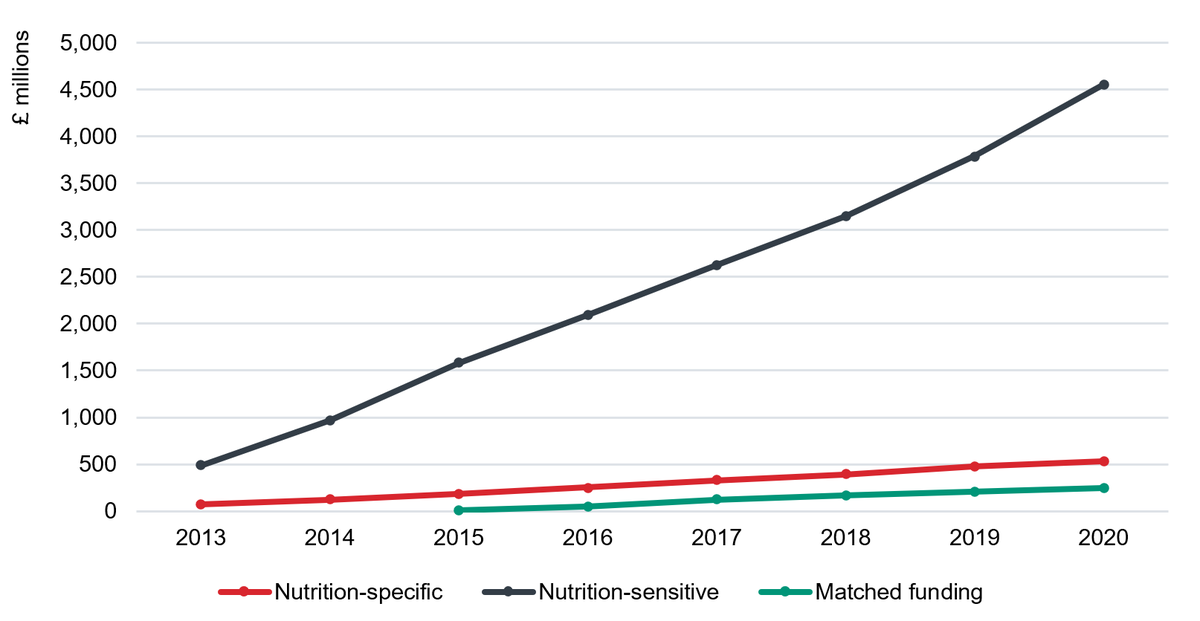

Nutrition-specific N4G commitment

As of 2020, the FCDO has cumulatively disbursed £530.2 million in nutrition-specific funding (excluding matched funding), just shy of its original N4G target by around £44.7 million. Compared with the average annual required investment (calculated equally across this eight-year period 2013–2020), FCDO’s annual nutrition-specific spending has fallen just short of target requirements (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The FCDO has not quite met its nutrition-specific N4G commitment

The FCDO’s N4G commitments and cumulative nutrition-specific ODA disbursements for 2013–2020

Line graph showing the FCDO’s N4G commitments and cumulative nutrition-specific ODA disbursements for 2013–2020

Notes: Totals exclude matched funding. Disbursements are presented in 2020 prices.

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on DAC CRS data, FCDO data, and OECD National Accounts Statistics: purchasing power parities (PPPs) and exchange rates.

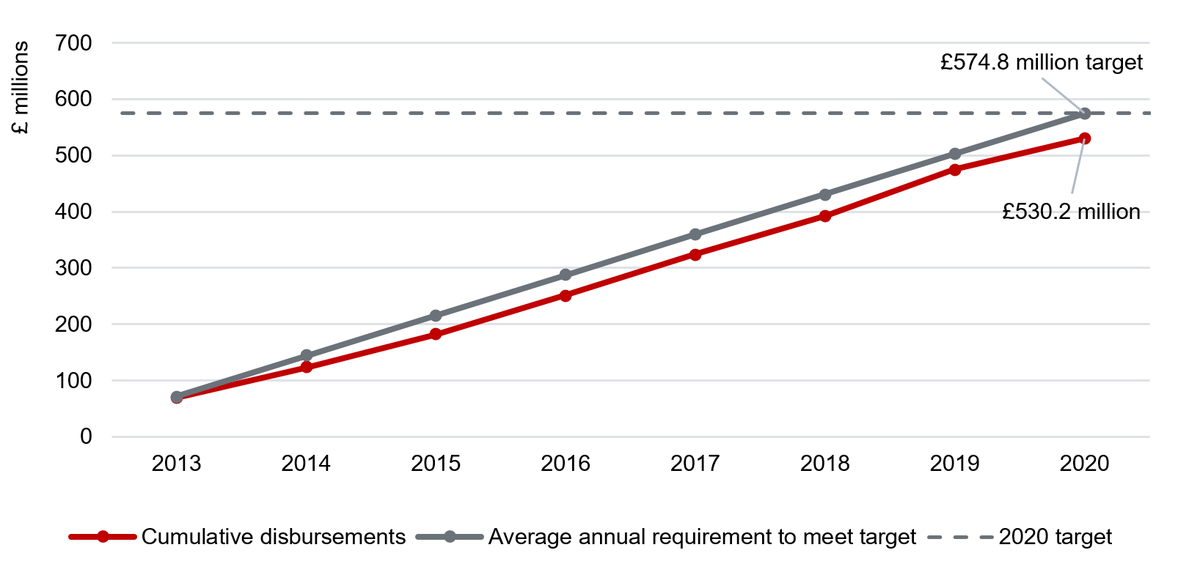

Nutrition-sensitive N4G commitment

As identified in 2020, the FCDO has exceeded its nutrition-sensitive target of £2.1 billion (Figure 3) and so the nutrition-sensitive N4G commitment has been met. In current, real-term prices, the FCDO exceeded this target early in 2017. As of 2020, the FCDO has cumulatively disbursed £4.6 billion to nutrition-sensitive interventions since 2013, more than double its original N4G target.

Figure 3: The FCDO has spent more than double its nutrition-sensitive N4G target

FCDO’s N4G commitments and cumulative nutrition-sensitive ODA disbursements for 2013–2020

Line graph showing FCDO’s N4G commitments and cumulative nutrition-sensitive ODA disbursements for 2013–2020

Notes: Disbursements are presented in 2020 prices.

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on DAC CRS data and OECD National Accounts Statistics: purchasing power parities (PPPs) and exchange rates.

Matched funding

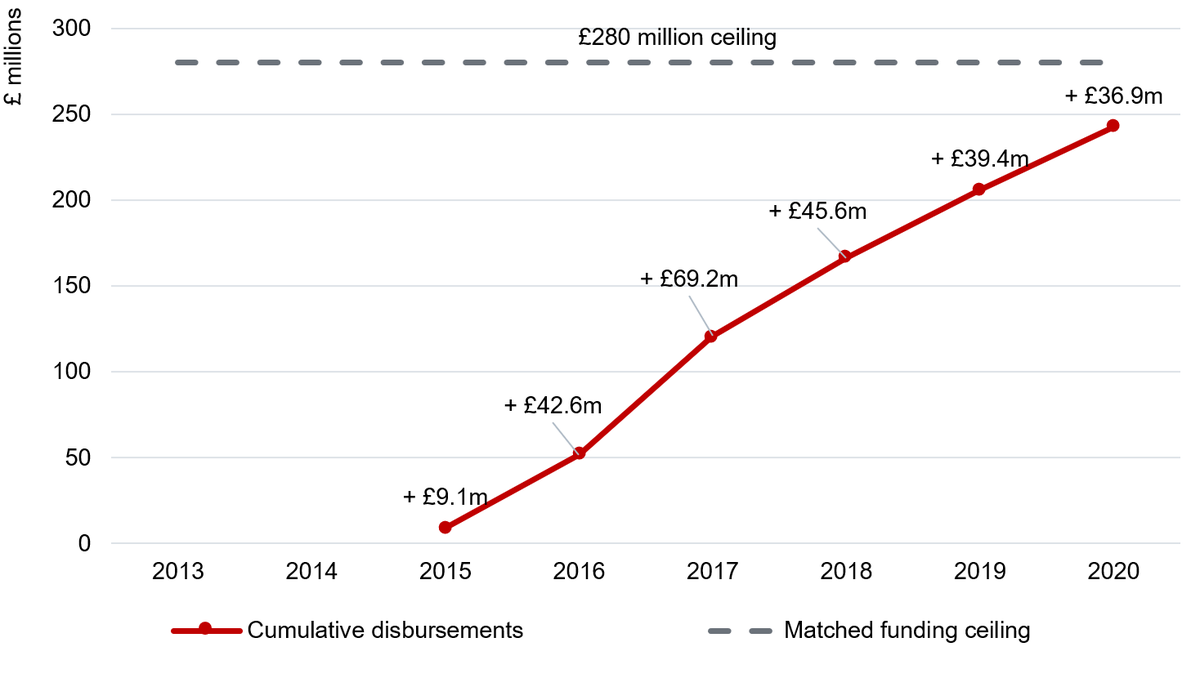

Since 2017, previous editions of this report have included assessments of the FCDO’s matched funding, though it should be noted the method of estimation was revised. Prior to 2021 (reporting on 2019 spending) the FCDO provided details of matched funding based on specific components of identified programmes. The sum of the value of these disbursements was considered the ‘matched funding spending’; it was used to estimate the FCDO’s total matched funding spending and was subtracted from calculations of nutrition-specific spending for the purposes of monitoring progress against N4G commitments. Since 2021, however, the FCDO has provided details of matched funding at the country office level, sharing subtotals of matched funding spending for each year since 2015.

Based on this data the FCDO has cumulatively disbursed a total of £242.8 million of nutrition-specific matched funding to partner organisations since 2013, £37.2 million short of the ceiling it had set of £280 million.

FCDO’s ODA disbursements to nutrition, 2010–2020

The FCDO’s cumulative matched funding ODA disbursements for 2013–2020

Line graph showing the FCDO’s cumulative matched funding ODA disbursements for 2013–2020

Note: Disbursements are presented in constant 2020 prices.

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on FCDO data and OECD National Accounts Statistics: purchasing power parities (PPPs) and exchange rates.

FCDO’s ODA disbursements to nutrition, 2010–2020

Overview

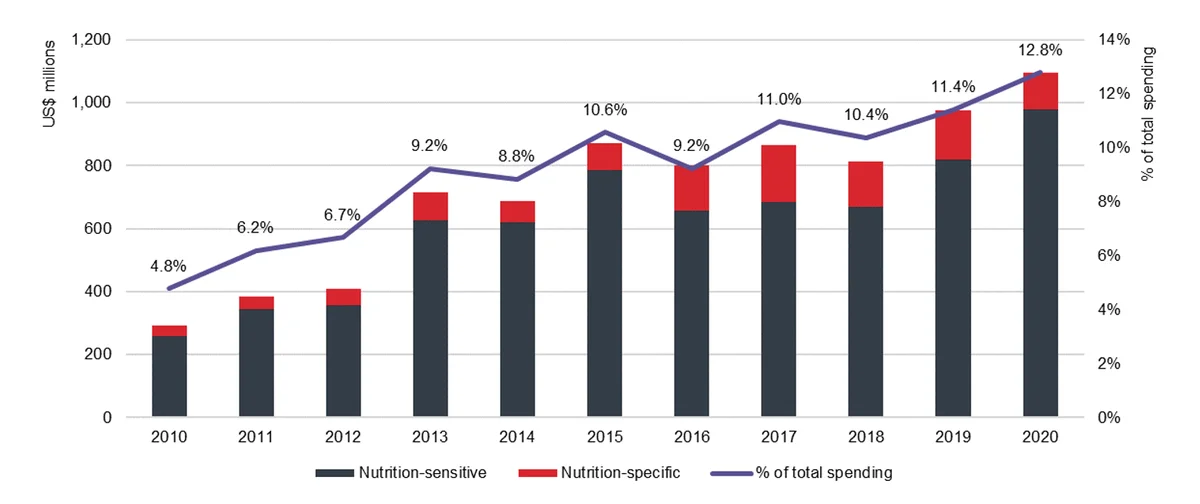

In 2020, FCDO’s total aid spending for nutrition, including matched funding, increased for the second consecutive year to reach a record US$1.1 billion, an increase of 12% equal to US$120.6 million (Figure 5).

While FCDO’s total aid spending for nutrition has increased, spending on nutrition-specific programmes decreased by a quarter, from US$156.5 million in 2018 to US$117.4 million in 2020. This is the lowest amount since 2015. Conversely, FCDO’s spending on nutrition-sensitive interventions increased by 19.5% from US$872.7 million in 2019 to US$979.5 million in 2020 – higher than any previous year.

In terms of amounts, and in line with previous years, FCDO continues to spend substantially more on nutrition-sensitive programmes, constituting 89.3% of overall nutrition spending, up slightly from 84.0% the previous year.

Proportional and relative to its total ODA spending, FCDO’s total nutrition spending increased in 2020, to a peak 12.8%.

Addendum:

Figure 5 was updated in June 2024 to correct an error affecting the published value for FCDO’s total aid spending for nutrition as a proportion of its total ODA spending. This was originally reported as 8.5% for 2020. The correct value is 12.8%.

Figure 5: FCDO’s total aid spending for nutrition increased for the second consecutive year

FCDO’s ODA spending for nutrition for 2010–2020

Bar chart showing FCDO’s ODA spending for nutrition for 2010–2020

Notes: Based on gross ODA disbursements. Constant 2020 prices.

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on DAC CRS data.

Table 1: FCDO’s ODA spending for nutrition for 2010–2020

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition-sensitive | 258.0 | 345.9 | 355.6 | 625.1 | 619.3 | 784.6 | 656.6 | 684.0 | 668.6 | 819.8 | 979.5 |

| Nutrition-specific | 34.0 | 38.5 | 54.4 | 89.3 | 69.1 | 85.9 | 144.0 | 182.3 | 146.4 | 156.5 | 117.4 |

| Total | 292.0 | 384.3 | 410.0 | 714.5 | 688.4 | 870.5 | 800.6 | 866.3 | 815.0 | 976.4 | 1096.9 |

Notes: Based on gross ODA disbursements. US$ millions. Constant 2020 prices.

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on DAC CRS data.

The proportion of total UK ODA provided by FCDO has increased in 2020 to 66.7% (of total UK ODA) compared with 63.5% in 2019.

Programmes

Despite spending a record amount, the actual total number of nutrition-related programmes supported by FCDO decreased for the second consecutive year by 16 to 100 programmes – the fewest observed in this series of assessments from 2010 to 2020 (Figure 6).

This portfolio included six nutrition-specific programmes (up from four in 2019), 69 nutrition-sensitive programmes (down from 76) and 25 programmes with both nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive components (down from 36).

The mean annual amount FCDO spent on a nutrition-related programme in 2020 was US$11.0 million, with nutrition-specific programmes costing an average US$7.5 million, nutrition-sensitive programmes US$9.6 million, and programmes with both nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive components US$14.3 million.

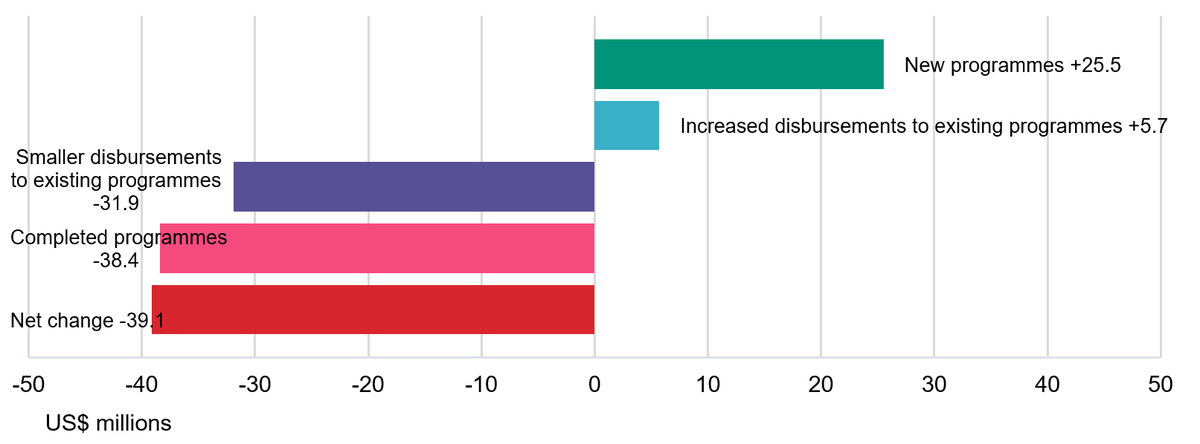

Nutrition-specific spending, 2019–2020

In 2020, while FCDO’s total aid spending for nutrition has increased, spending on nutrition-specific programmes (including through matched funding) decreased by net US$39.1 million, or 25%.

The details of this decreased spending are:

- New programmes with new disbursements, +US$25.5 million

- Increased disbursements to existing programmes, +US$5.7 million

- Smaller disbursements to existing programmes, -US$31.9 million

- Completed programmes with no new disbursements, -US$38.4 million

Figure 7: FCDO’s nutrition-specific spending decreased by US$39.1 million in 2020

Changes to nutrition-specific disbursements, 2019–2020

Chart showing changes to nutrition-specific disbursements, 2019–2020

Notes: ‘New programmes’ are those with no disbursements before 2020. ‘Completed programmes’ are those with disbursements in 2019 but none in 2020. ‘Increased disbursements’ and ‘smaller disbursements’ refer to spending changes on existing programmes. Constant 2020 prices.

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on DAC CRS data.

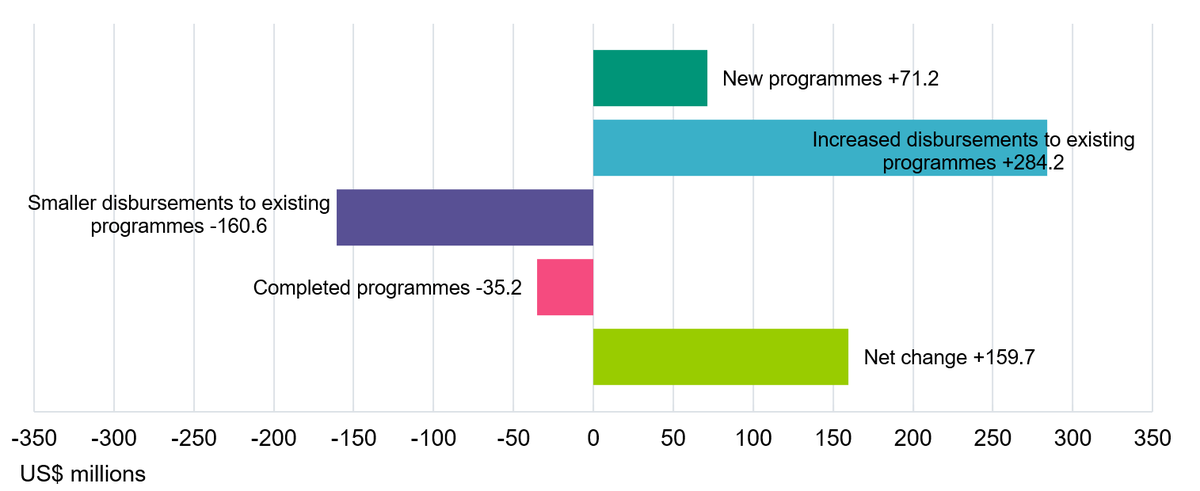

Nutrition-sensitive spending, 2019–2020

FCDO’s total spending on nutrition-sensitive programmes increased by net US$159.7 million in 2020, similar to the increase between 2018 and 2019, representing a 19.5% increase.

The details of this increased spending are:

- New programmes with new disbursements, +US$71.2 million

- Increased disbursements to existing programmes, +US$284.2 million

- Smaller disbursements to existing programmes, -US$160.6 million

- Completed programmes with no new disbursements, -US$35.2 million.

FCDO nutrition-sensitive ODA by sector and purpose

Changes to nutrition-sensitive disbursements, 2019–2020

Chart showing changes to nutrition-sensitive disbursements, 2019–2020

Notes: ‘New programmes’ are those with no disbursements before 2020. ‘Completed programmes’ are those with disbursements in 2019 but none in 2020. ‘Increased disbursements’ and ‘smaller disbursements’ refer to spending changes on existing programmes. Constant 2020 prices.

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on DAC CRS data.

FCDO nutrition-sensitive ODA by sector and purpose

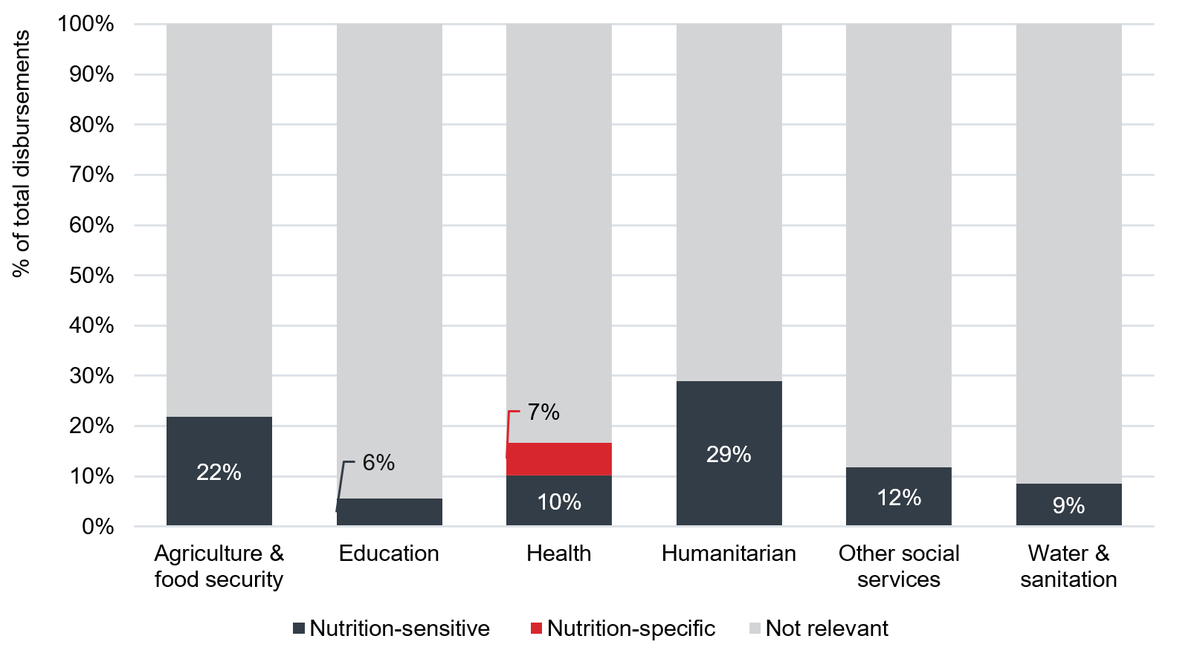

While nutrition-specific spending by definition falls under the health sector in the DAC CRS system, FCDO’s nutrition-sensitive spending is also found elsewhere, across a broad variety of sectors.

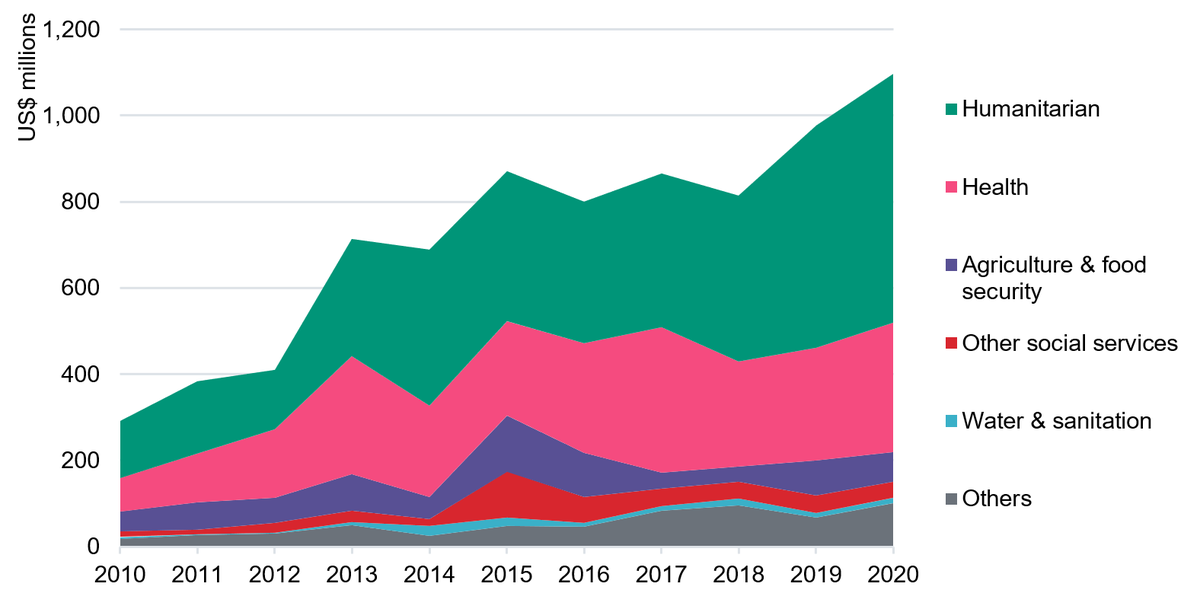

Sectors

Since this series of assessments began, covering 2010 onwards, the majority of FCDO’s nutrition-sensitive spending by sector has been among humanitarian programmes. In 2020 nutrition-sensitive spending in this sector reached a record US$577.1 million, a significant US$ 62.8 million increase over 2019 levels and representing over half (52.6%) of FCDO’s total nutrition-sensitive spending. This continues a trend of annual increases observed since 2016.

The health sector has similarly been significantly represented by FCDO’s nutrition-sensitive spending since 2010, each year accounting for the greatest amounts after the humanitarian sector and representing around a third of FCDO’s total nutrition-sensitive spending each year. Spending increased for a second consecutive year, by US$38.9 million to US$300.9 million in 2020, and equal to 27.4% of FCDO’s total nutrition-sensitive spending.

While spending in these two key sectors increased, nutrition-sensitive spending decreased in the agriculture and food security sector, by US$12.5 million to US$68.1 million in 2020, and in the social services sector, by US$3.4 million to US$37.8 million. Nutrition-sensitive spending also decreased, though by lesser volumes, in the environment sector (by US$2.1 million to US$6.9 million, the least since 2014), the business and industry sector (by US$0.6 million to US$1.9 million) and to the infrastructure sector (by US$0.3 million to US$1.6 million).

Nutrition-sensitive spending on education programmes increased significantly, by a record US$23.2 to a peak US$31.7 million in 2020. The is attributable to increased disbursements to the nutrition-sensitive education components of an existing multi-sector programme in Bangladesh with the NGO BRAC: “the BRAC Strategic Partnership Arrangement – Phase II”, programme code GB-1-204916. Spending also increased in governance and security programmes, by US$11.7 million to a record US$34.9 million. Spending on water & sanitation also increased slightly, by US$1.7 million to US$11.8 million in 2020. See Appendix 5 for more.

Across the entire period (2013–2020) we observe huge growth in nutrition-sensitive spending among the humanitarian and health sectors, alongside smaller increases and more variable spending across other sectors.

Figure 9: Humanitarian nutrition-sensitive spending increased for the fourth consecutive year, reaching a record US$577.1 million

Nutrition-sensitive disbursements by sector, 2010–2020

Chart showing nutrition-sensitive disbursements by sector, 2010–2020

Notes: Constant 2020 prices. ‘Others’ includes ‘Environment’, ‘Education’, ‘Governance and security’, ‘Business and industry’, ‘Infrastructure’ and ‘General budget support’.

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on DAC CRS data.

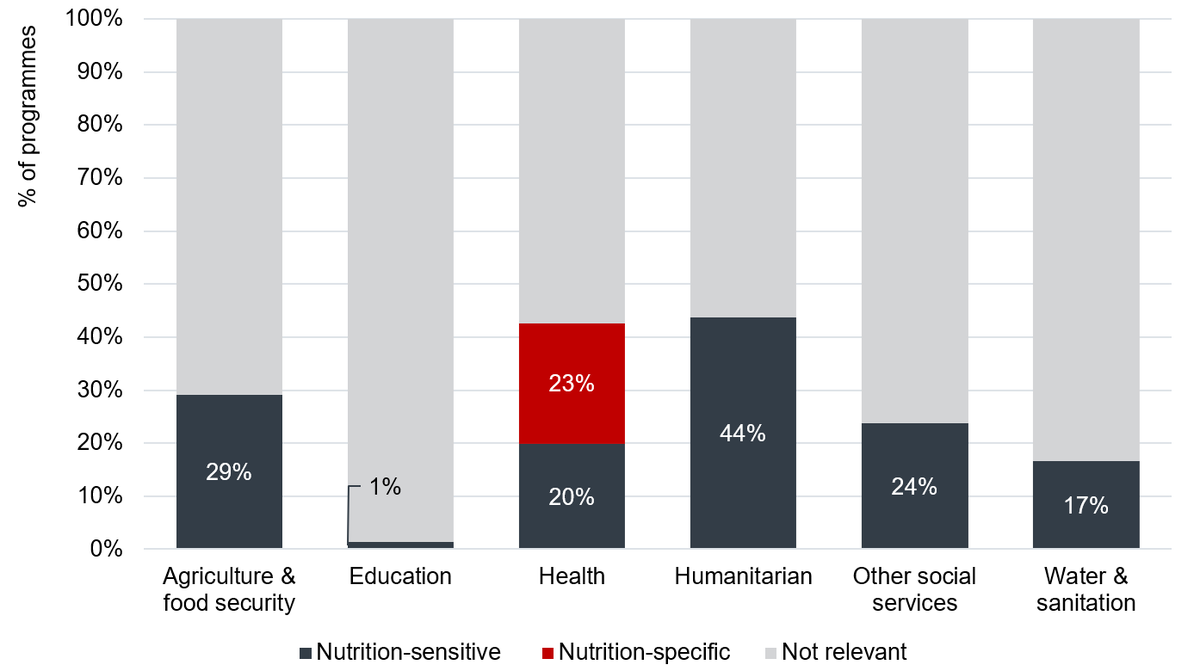

By share of FCDO’s total spending in each sector, 29% of FCDO’s humanitarian spending was nutrition-sensitive in 2020 (Figure 10), up slightly from 28% in 2019. By number of programmes, 44% of FCDO’s humanitarian programmes were nutrition-sensitive to some degree (down from 64% in 2019) (Figure 11).

Over a fifth (22%) of FCDO’s agriculture and food security spending was nutrition-sensitive in 2020, up from 20% in 2019, equal to 29% of all programmes in that sector. The share of health spending that was nutrition-sensitive also increased slightly in 2020, from 8% to 10%. An additional 7% was nutrition-specific, down from 12% in 2019, and 12% of other social services spending and 24% of programmes were nutrition-sensitive in 2020, down from 16% and up from 27% respectively.

The proportion of water & sanitation spending that was nutrition-sensitive increased from 5% to 9% in 2020, though the proportion of water & sanitation programmes decreased from 23% to 17%.

As in 2019, by this measure, the business and industry sector was the least nutrition-sensitive, with just 0.2% of disbursements being nutrition-sensitive in 2020.

Figure 11: 44% of FCDO’s humanitarian programmes were nutrition-sensitive in 2020

Programmes by key sectors and type, 2020

Bar chart showing programmes by key sectors and type, 2020

Notes: Proportion of programmes calculated using total number of FCDO components.

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on DAC CRS data.

Purpose codes

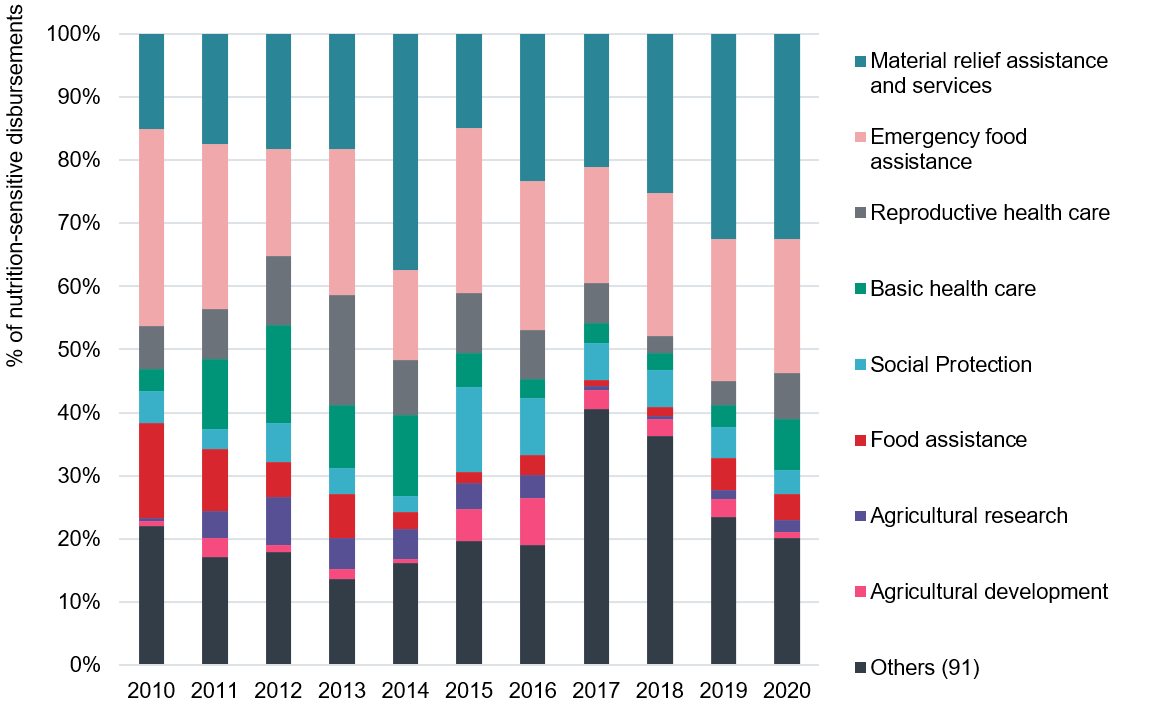

Purpose codes offer additional detail on the nature of FCDO’s nutrition-sensitive spending across sectors. The bulk of FCDO’s nutrition-sensitive spending has fallen under a select number of purpose codes since 2010, although the distribution across these codes fluctuates.

The distribution of spending across purpose codes in 2020 shows a similar pattern to that seen in recent years, with few drastic changes (Figure 12). ‘Material relief assistance and services’ accounted for the greatest amounts and share, as it has since 2016 with ‘emergency food assistance’ accounting for the second greatest amount (US$319.1 million, or 33%, and US$208 million, or 21%, respectively).

Nutrition-sensitive spending increased among ‘basic health care’ by US$50.5 million to US$78.8 million in 2020, equal to 8% of FCDO’s total nutrition-sensitive spending, and similarly among ‘reproductive health care’ by US$39.0 million to US$70.5 million in 2020, equal to 7%.

Spending decreased among ‘agricultural development’ (down US$15.0 million to US$8.5 million in 2020), though increased among ‘agricultural research’ (up US$8.6 million to US$20.0 million).

Among 91 ‘other’ purpose codes not specified in Figure 12, nutrition-sensitive spending increased to 19, remained constant to 24, and decreased to 48. By volume, the greatest increases were among ‘primary education’ (up US$28.4 million to US$31.7 million in 2020) and ‘public sector policy and administrative management’ (up US$13.0 million to US$28.9 million). The greatest decreases were among ‘rural development’ (down US$12.0 million from 2019 with zero spending in 2020) and ‘relief co-ordination and support services’ (down US$10.4 million to US$27.9 million). See Appendix 5 for more.

Recipients of nutrition ODA disbursements

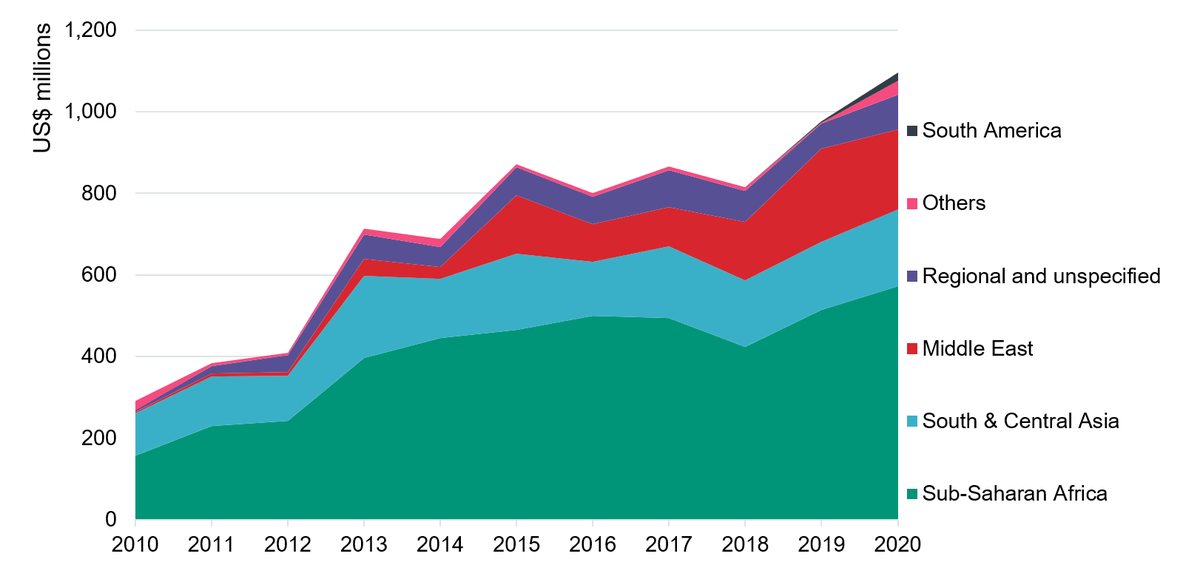

Regions

While FCDO’s total aid spending for nutrition has increased substantially since 2010, the geographic distribution of supported programmes has remained fairly consistent across regions.

In 2020, FCDO’s net spending increased to all regions except the Middle East.

FCDO’s total nutrition-related spending increased by the greatest amount to sub-Saharan Africa – by US$56.6 million to US$571.8 million in 2020, an 11% increase – which remains the greatest recipient region by volume. Spending also increased in South and Central Asia by US$22.1 million to US$188.5 million in 2020, a 13% increase, and in South America by US$15.6 million to US$19.9 million, a 363% increase.

Spending in the Middle East, which spiked in 2019 due to activity in Yemen, has since decreased by 14% in 2020, down US$32.1 million to US$196.1 million in 2020.

Figure 13: Net spending increased to all regions except the Middle East

Nutrition disbursements by region, 2010–2020

Lorem ipsum

Notes: Constant 2020 prices. ‘Unspecified’ refers to funding not allocated to a single region. ‘Others’ include funding allocated to the West Indies and to Africa with no further specification.

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on DAC CRS data.

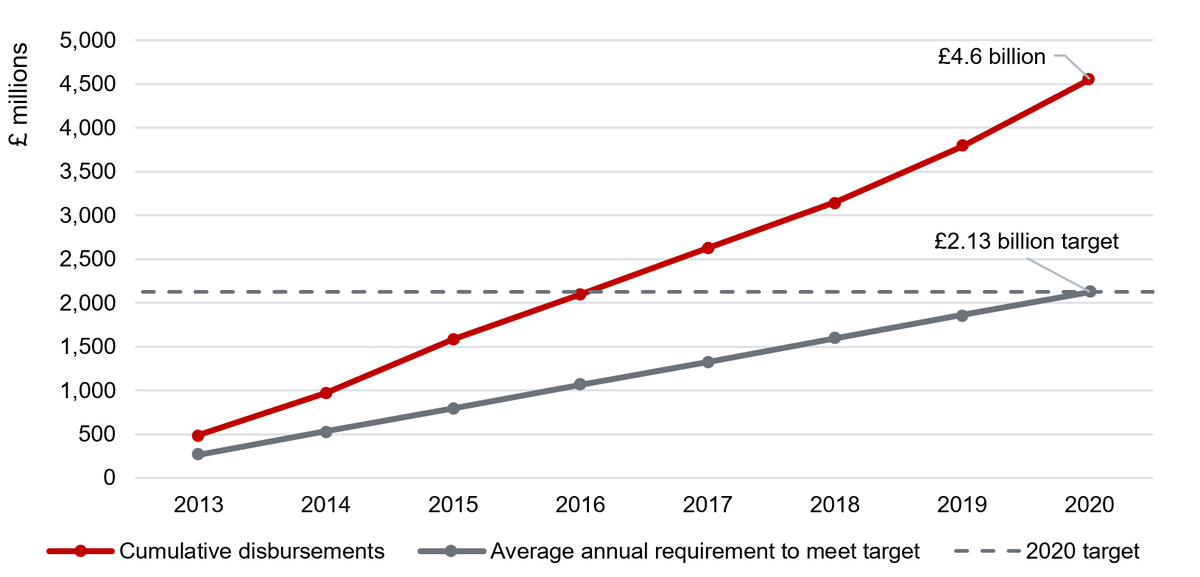

Countries

In 2020 the total number of countries supported by an FCDO nutrition-related programme has decreased, from 36 in 2019 to 32 (Figure 14).

The pattern of funding in 2020 is similar to 2019, in that most countries received either nutrition-sensitive support exclusively or received both nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive support, while Yemen, the greatest country recipient by volume, received only nutrition-sensitive support.

Seventeen countries received a combination of nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive support, five of which received greater amounts of nutrition-specific support – Pakistan, Kenya, Zambia, Eritrea and India. Fifteen countries received exclusively nutrition-sensitive support in 2020, including Yemen with US$178.1 million, Ethiopia with US$56.8 million, and Afghanistan with US$45.7 million. No country received only nutrition-specific support.

FCDO has increased total nutrition-related spending in 16 countries from 2019 to 2020 including, by magnitude of change, Zimbabwe (up US$28.2 million to US$73.4 million), Sudan (up US$28.0 million to US$53.5 million), Democratic Republic of the Congo (up US$27.9 million to US$59.1 million) and Somalia (up US$ 26.6 million to US$54.0 million). There were no countries that received FCDO disbursements in 2020 that did not in 2019.

Spending decreased to 20 other countries, including four countries where nutrition-related programmes ceased; Saint Helena, Montserrat, Jordan and Colombia each received relatively small amounts in 2019 and did not receive any nutrition-related disbursements in 2020. Spending decreased most notably to Mozambique (down US$24.2 million to US$12.3 million in 2020) and Yemen (down US$20.8 million to US$178.1 million)

As FCDO’s total nutrition-related spending has increased and the number of supported countries has decreased, the mean annual amount received by any country has increased from US$24.7 million to 30.0 million in 2020.

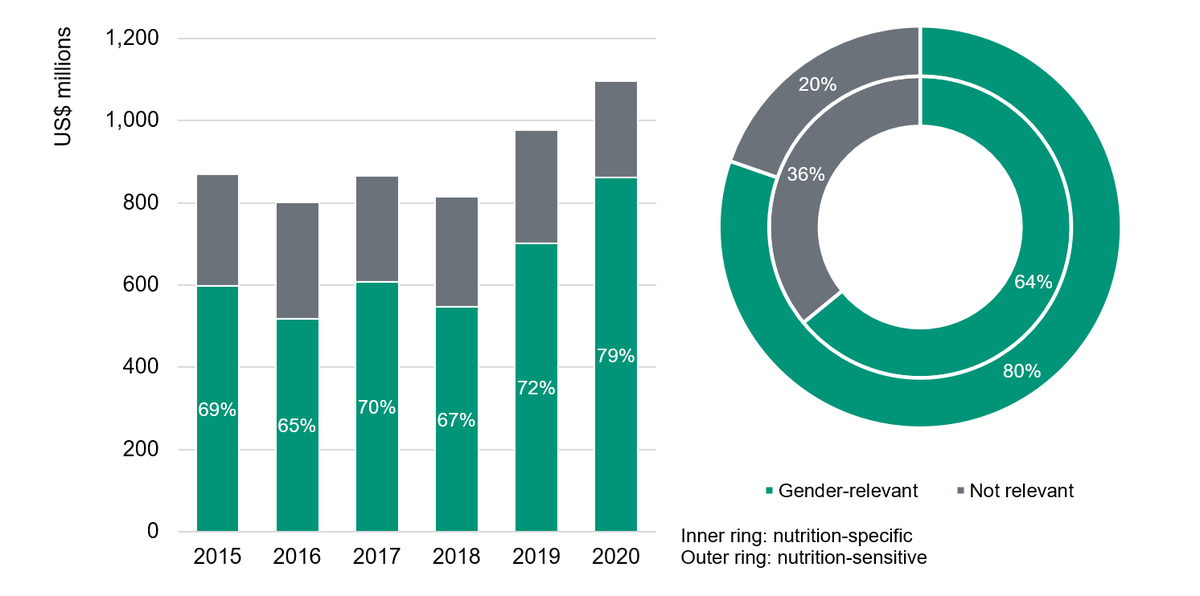

FCDO’s aid spending for nutrition and the gender marker

ODA relevant to gender equality and women’s rights is identified using the OECD DAC’s gender equality policy marker, defined as “a statistical tool to record aid activities that target gender equality as a policy objective” (OECD, 2016).

A marker is used by reporting organisations to signal the policy objectives of a programme – in this case, gender equality. Reporters can mark a programme as having either a significant or principal gender equality policy objective, signalling the relevance of each marked programme. Those marked as ‘principal’ have gender equality as a primary objective, whereas programmes marked as ‘significant’ may have other key objectives, while retaining gender equality as a deliberate objective. The following section refers to the sum of ODA associated with programmes marked as ‘significant’ and ‘principal’. It should be stressed that ODA identified in this way should be considered an estimate only.

FCDO screened 100% of its programmes using the OECD DAC gender equality policy marker for the second consecutive year. The resulting data show that the proportion of the FCDO’s nutrition spending marked relevant to gender equality increased for the second consecutive year, reaching a record 79% in 2020, equal to US$862 million in gender-relevant nutrition ODA (Figure 16).

Between FCDO’s nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive spending, a greater proportion of FCDO’s nutrition-sensitive spending was gender relevant – 80% compared with 64% of nutrition-specific spending – a similar pattern to previous years.

In 2020, FCDO also spent US$1.6 million of nutrition-sensitive ODA on programmes specifically designed for ending violence against women and girls, identifiable using the OECD DAC purpose codes.

Appendix 1: Methodology

Gender-relevant nutrition disbursements, 2015–2020

Lorem ipsum

Notes: Gender-relevant refers to disbursements reported as having a significant or principal gender equality policy objective. Constant 2020 prices.

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on DAC CRS data.

Appendix 1: Methodology

Identifying nutrition-specific ODA programmes

Donors reporting to the CRS, including FCDO, must specify in some detail the sector [2] that their ODA investments intend to support, using a defined list of purpose codes that classify activities – enabling a view of each donor’s support across key sectors.

The SDN methodology defines all programmes recorded under the ‘basic nutrition’ CRS purpose code (12240) as ‘nutrition-specific’. In 2017, a revised code was adopted that included some amendments, most notably the removal of school feeding and household food security.

At the time of reporting for 2019 spending, as assessed in this report, this code captures reported spend on (OECD, 2021):

- Micronutrient deficiency identification and supplementation

- Infant and young child feeding promotion, including exclusive breastfeeding

- Non-emergency management of acute malnutrition and other targeted feeding programmes (including complementary feeding)

- Staple food fortification, including salt iodisation

- Nutritional status monitoring and national nutrition surveillance

- Research, capacity building, policy development, monitoring and evaluation in support of these interventions.

Generally, donors report their programmes to the CRS either under a single purpose code, based on the programme’s main objective or sector, or under a ‘multi-sector’ purpose code. FCDO’s reporting to the CRS is more detailed, as is that of some other donors, such as Canada. FCDO divides its programmes into different components and assigns each a relevant CRS purpose code. Each component appears in the CRS as a separate record. In some cases, an FCDO CRS record represents the whole programme. In others, a record represents only part of a broader programme, with the other components appearing as separate purpose codes.

Because of this, for the original 2010–2012 assessment, the application of the SDN methodology to FCDO’s CRS records under the ‘basic nutrition’ purpose code was adapted, with the agreement of the SDN. In this analysis, all FCDO programme components coded to ‘basic nutrition’ in the CRS are counted in full as nutrition-specific. Spending recorded against these components is used to determine FCDO’s total ODA funding to nutrition-specific interventions.

Other components of these programmes recorded under any other CRS purpose code have been classified as ‘nutrition-sensitive’ (see Appendix 2 for a record of programmes with both specific and sensitive components).

Identifying nutrition-sensitive ODA programmes

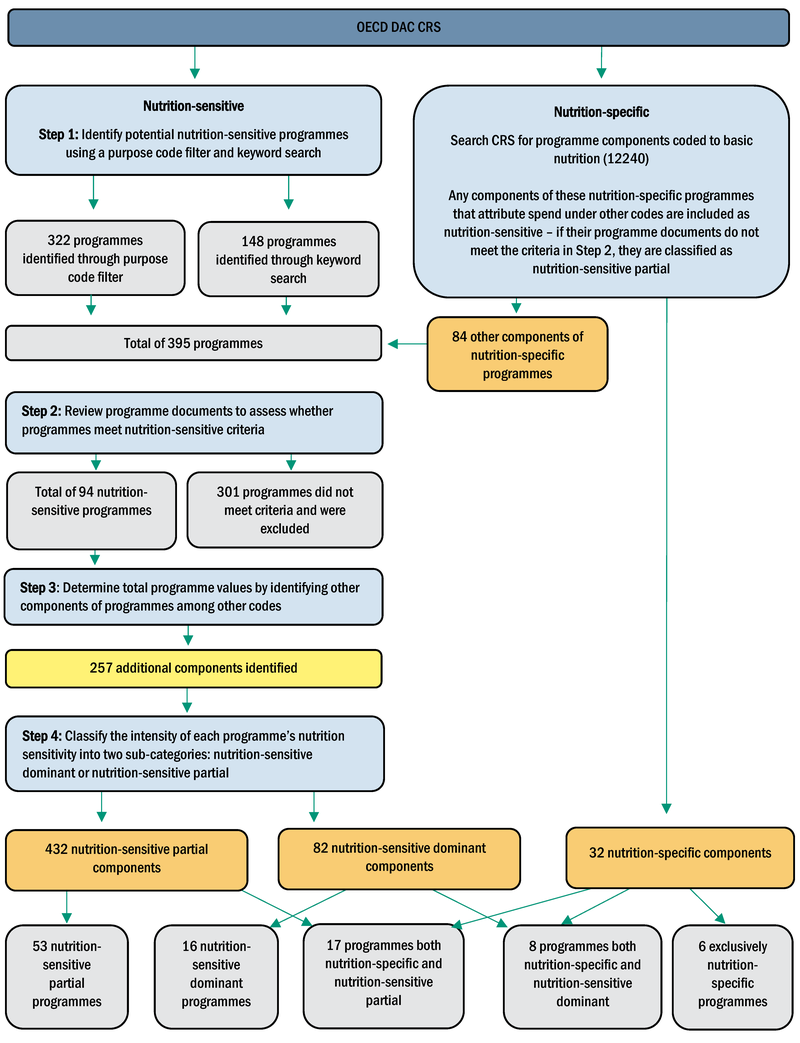

The SDN methodology uses a three-step approach to identify nutrition-sensitive programmes. In the methodology used, an additional step is needed to account for FCDO’s detailed CRS reporting. The steps used in this analysis are outlined below.

Step 1: Identify potentially nutrition-sensitive programmes

Programmes that are likely to be nutrition sensitive are first identified in the CRS database using a purpose code filter and a keyword search. The purpose code filter selects all programmes coded under relevant nutrition-sensitive purpose codes (see Table 2). A keyword search is applied to the description field of all other CRS records under the remaining purpose codes (Box 1). The purpose code filter and keyword search yield a pool of potentially nutrition-sensitive records. As explained above, for FCDO, these records represent programme components rather than whole programmes.

Table 2: DAC CRS purpose codes used to identify nutrition-sensitive programmes

FOOD SECURITY AND AGRICULTURE

Availability

31110 Agricultural policy and administrative management

31120 Agricultural development

31140 Agriculture water resources

31150 Agricultural inputs

31161 Food crop production

31163 Livestock

31166 Agricultural extension

31181 Agricultural education/training

31182 Agricultural research

31191 Agricultural services

31193 Agricultural financial services

31194 Agricultural cooperatives

31310 Fishing policy and administrative management

31320 Fishery development

31381 Fishery education and training

43040 Rural development

Accessibility

16010 Social welfare services

16011 Social protection

52010 Food aid/food security programs

72010 Material relief assistance and services

72040 Humanitarian/emergency relief

72050 Relief coordination, protection and support services

73010 Reconstruction, relief and rehabilitation

PUBLIC HEALTH AND WATER AND SANITATION

Public health (including reproductive health)

12110 Health policy and administrative management

12220 Basic health care

12250 Infectious disease control

12261 Health education

12281 Health personnel development

13020 Reproductive healthcare

13022 Maternal health (including neonatal health)

Sanitation

14030 Basic drinking water supply and sanitation

14032 Basic sanitation

Drinking water

14031 Basic drinking water supply

CARE ENVIRONMENT

Gender empowerment

15170 Women’s equality organisations and institutions

OTHER

51010 General budget support

Box 1

Keywords used to identify nutrition-sensitive programmes

Aflatoxin; biofortification; breastfeeding; cash transfer; child feeding; CMAM; community management of acute malnutrition; deworming; diarrheal disease; diet; dietary diversification; direct feeding; enteropathy; feeding; feeding program; feeding programme; food intake; food intake; food security; food subsidy; food voucher; fortification; GAM; global acute malnutrition; garden; gastrointestinal illness; global nutrition coordination; growth monitoring; growth monitoring and promotion; handwashing; helminth; hunger; hygiene; IUGR; intrauterine growth restriction; iodine; iron; iron-folic acid; iron folic acid; low birthweight; maternal feeding; MAM; mineral; moderate acute malnutrition; malnutrition; micronutrient; nutrition; nutrition education; ready to use therapeutic food; ready-to-use therapeutic food; ready-to-use-therapeutic-food; RUTF; SAM; severe acute malnutrition; Scaling Up Nutrition; school feeding; stunting; supplement; supplementation; under nutrition; undernutrition; under-nutrition; under weight; underweight; under-weight; vitamin; wasting; zinc.

Step 2: Review programme documents to assess whether it meet nutrition-sensitive criteria

The programme documents for all components identified in Step 1 are reviewed to determine whether they are nutrition-sensitive. This assessment primarily uses publicly available documents published through the FCDO’s Development Tracker . Programmes with insufficient publicly available information are raised with FCDO officials, who provide relevant documentation to enable an assessment.

To qualify as nutrition-sensitive, a programme must meet three of the following criteria. The programme must:

- be aimed at individuals (specifically women, adolescent girls or children)

- include nutrition as a significant objective or indicator

- contribute to at least one nutrition-sensitive outcome as per the SDN methodology (see Table 3).

Table 3: Examples of nutrition-sensitive outcomes from the SDN methodology

Nutrition-sensitive outcomes

A. Individual level (women, adolescent girls or children):

- Increase purchasing power of women (examples: safety nets, cash transfers).

- Improve access to nutritious food for women, adolescent girls and/or children (examples: agriculture/livestock diversification, biofortification, food safety, increased access to markets).

- Improve diet in quality and/or quantity for women, adolescent girls or children (examples: promotion of quality/diversity, nutritious diets, quantity/energy intake in food-insecure households, stability, micronutrient intake, vouchers, access to markets).

- Improve access of women or adolescent girls or children to primary health care (examples: maternal health care, child health care, reproductive health care, supplementation, therapeutic feeding, support with breastfeeding).

- Improve access to childcare (i.e. childcare not supplied through the health services).

- Improve women’s or adolescent girls’ or children’s access to water, sanitation and hygiene (examples: access to latrines, access to safe water, improvement of hygiene).

- Improve access to education/school for adolescent girls.

- Improve knowledge/awareness on nutrition for relevant audiences (examples: inclusion of nutritional education in primary and secondary education curricula, TV and radio spots addressing vulnerable households and decision-makers, nutrition awareness campaigns).

- Improve empowerment of women (examples: access to credit, women-based smallholder agriculture, support to women’s groups).

B. National level:

- Improve governance of nutrition (examples: increased coordination of actors and policies for nutrition, establishment of budgets specifically contributing to nutrition, improvement of institutional arrangements for nutrition, improved nutrition information systems, integration of nutrition in policies and systems).

- Increase nutrition-sensitive legislation (examples: food-fortification legislation, right-to-food, legislation for implementing the Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes, food safety).

C. Research:

- Increased research with nutrition objectives.

While identifying explicit nutrition targets and objectives among programme documents is straightforward, applying the first criterion (aimed at individuals) is more subjective. The SDN methodology requires a programme to intend to improve nutrition for women or adolescent girls or children to be considered nutrition-sensitive. The methodology adds that, “this does not necessarily entail targeting women or children, because actions targeted at households, communities or nations can also be designed to result in improved nutrition for women and children. It entails, though, an intention to achieve results and measure them at the level of women, adolescent girls or children” (SDN, 2013).

This analysis considered a programme to be aimed at individuals when there was evidence of explicit or implicit intent among programme documents to achieve results and measure them at an individual level. In the case of FCDO, some nutrition-sensitive programmes track progress at the household level. Programmes that only tracked progress at the household level and not at the individual level (e.g. numbers of children or numbers of women) were only considered to be aimed at individuals when there was at least a clearly stated objective to improve nutrition of individuals.

A programme’s objectives and indicators are considered nutrition-sensitive if they demonstrate an intention to improve nutrition (e.g. ‘improving malnutrition’ and ‘reducing incidence of malnutrition’) or refer to actions that do this (e.g. through improvement in dietary diversity, breastfeeding and vitamin supplementation). Programme objectives or indicators that focus only on actions that could lead to improved nutrition outcomes, but do not refer to nutrition explicitly, are not considered nutrition-sensitive (e.g. cash transfers, access to education or sanitation services not explicitly aimed at improving nutrition).

Finally, nutrition-sensitive programmes must contribute towards nutrition-sensitive outcomes as defined in the SDN methodology. Only when all three of these criteria are met can a programme qualify as nutrition-sensitive.

Appendix 3 provides examples of how these criteria are applied to specific programmes.

Step 3: Determine the total programme spend for nutrition-sensitive programmes in the case of FCDO’s CRS records

As FCDO reports at the component level, it is possible that a programme identified as nutrition-sensitive under the criteria described in Step 2 will have components elsewhere in the CRS database that are not captured in Step 1. In some cases, not all components are reported using one of the codes or captured using the keywords. To account for this, the additional components of nutrition-sensitive programmes are identified manually by searching for components with the same programme identification number in the CRS, in line with what was agreed by SDN members for the original 2010–2012 FCDO nutrition-spending assessment. For each programme, total spend is calculated as the sum of all the programme’s components.

Step 4: Classify nutrition-sensitive programmes as ‘dominant’ or ‘partial’

The final step of the SUN methodology classifies nutrition-sensitive programmes as one of two sub-categories: ‘dominant’ or ‘partial’, depending on the extent to which programmes contribute to nutrition-sensitive outcomes.

The SUN methodology requires that:

- when the full programme (its main objective, results, outcomes and indicators) is nutrition-sensitive, the programme is classified as ‘nutrition-sensitive dominant’ and the total spend for the programme is counted

- when part of the programme (e.g. one of the objectives, results, outcomes or indicators) is nutrition-sensitive, but also aims to address other issues, the programme is classified as ‘nutrition-sensitive partial’ and 25% of the programme spend is counted.

Appendix 3 provides examples of how programmes are assessed as dominant or partial.

Appendix 4 provides an illustration of these steps.

ODA disbursements and commitments

The CRS database has two measures of ODA: ‘commitments’ and disbursements’. Commitments are a formal obligation to disburse funds; disbursements are the funds that donors have actually provided. Commitments and disbursements from a donor will differ by year. This is because commitments often relate to programmes that disburse funds over a number of years. Also, disbursements may be made where no previous commitments existed, and the final disbursed cost of a programme may differ from the originally committed amount.

As disbursements measure the resources transferred to developing countries in a given reporting year, this analysis reports primarily on FCDO’s disbursements.

Constant versus current prices

In this report, FCDO’s spending on nutrition is assessed and expressed in constant US$ 2020 prices. This negates to a degree the effects of annual exchange rate changes and domestic price inflation on the way spending trends appear. This can also allow for more meaningful comparisons over time.

Consistent with the approach used in previous assessments, constant US$ prices are calculated from financial data as reported to the OECD DAC CRS and the OECD DAC’s deflators.

Spending figures presented in previous reports are also presented in a constant series, aligned with the latest year for which there was available data. This report on FCDO’s spending up to 2020 presents data in a constant 2020 series.

Table 4: Details of programmes with both nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive components active in 2020

Appendix 3: Determining the level of nutrition sensitivity of programmes: worked examples

| Number | Programme title | Programme classification |

|---|---|---|

| 204019 |

South Sudan Humanitarian Programme

(HARISS) 2014 - 2020 [GB-1-204019] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

partial |

| 204189 |

Burma UK Health Partnership Programme

[GB-1-204189] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

partial |

| 204196 |

Burma Humanitarian Assistance and

Resilience Programme [GB-1-204196] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

partial |

| 204457 |

Complementary food production (CHAI)

[GB-1-204457] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

partial |

| 204477 | Exiting Poverty in Rwanda [GB-1-204477] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

partial |

| 204608 |

Design work for a new programme on food

systems for nutrition [204608] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

partial |

| 204903 |

Somali Health and Nutrition Programme

(SHINE) 2016-2021 [GB-1-204903] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

partial |

| 204916 |

Strategic Partnership Arrangement II

between DFID and BRAC [GB-1-204916] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

partial |

| 205206 |

Building Resilience and an Effective

Emergency Refugee Response (BRAER) [GB-1-205206] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

partial |

| 300158 |

Health Systems Strengthening and delivery

of basic services [300158] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

partial |

| 300163 |

Supporting a Resilient Health System in

Zimbabwe (SRHS) [GB-GOV-1-300163] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

partial |

| 300196 |

Responding to Protracted Crisis in Sudan:

Humanitarian Reform, Assistance & Resilience Programme [GB-GOV-1-300196] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

partial |

| 300414 |

Access to quality essential healthcare for

the disadvantaged including disabled people [300414] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

partial |

| 300139 |

Kenya Integrated Refugee and Host

Community Support Programme (PAMOJA) [GB-GOV-1-300139] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

partial |

| 300495 | LAFIYA - UK Support for Health in Nigeria |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

partial |

| 203852 |

Pathways to Prosperity for Extremely Poor

People in Bangladesh (PPEPP) [GB-1-203852] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

partial |

| 203864 | Better Health in Bangladesh [GB-1-203864] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

partial |

| 201874 |

Working to Improving Nutrition in Northern

Nigeria (WINNN) [GB-1-201874] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

dominant |

| 202488 |

Provincial Health and Nutrition Programme

[GB-1-202488] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

dominant |

| 203224 |

Strategic Health and Nutrition Partnership

[GB-1-203224] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

dominant |

| 203551 |

Tackling Maternal and Child Undernutrition

Programme- Phase II [GB-1-203551] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

dominant |

| 203631 |

Addressing Stunting in Tanzania Early

Programme [GB-1-203631] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

dominant |

| 203981 |

Linking Agribusiness and Nutrition in

Mozambique [GB-1-203981] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

dominant |

| 204131 |

Ending the Cycle of Undernutrition in

Bangladesh - Suchana [nutsen] [GB-1-204131] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

dominant |

| 300478 |

Nutrition, health and sanitation support

in Eritrea [GB-GOV-1-300478] |

Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive

dominant |

Notes: Nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive dominant components were counted in full (100%). In line with the SUN methodology, 25% of nutrition-sensitive partial components were counted.

Appendix 3: Determining the level of nutrition sensitivity of programmes: worked examples

Example of a nutrition-sensitive programme

Support to UNICEF cholera, nutrition, malaria and primary health care programmes for the South Sudan Humanitarian Assistance and Resilience Building programme. Programme code GB-GOV-1-204019.

This programme meets all three of the criteria:

- Aimed at individuals: Number of children (6–59 months), women, adolescents treated with severe or moderate acute malnutrition

- Significant nutrition objective or indicator: Number of children (6–59 months), women, adolescents treated with severe or moderate acute malnutrition

- Contribution to nutrition-sensitive outcomes: Improve women’s or adolescent girls’ or children’s access to water, sanitation and hygiene; improved access to water, hygiene and sanitation facilities.

This programme is therefore classified as nutrition-sensitive .

Example of a discounted programme

Agribusiness Africa Round 3 Women's Economic Empowerment in Agriculture. Programme code GB-GOV-1-200094.

This programme does not meet all three criteria:

- Aimed at individuals: The programme does not have any (direct) actions relating to improving nutrition

- Significant nutrition objective or indicator: This programme has no evidence of a nutrition objective or indicator

- Contribution to nutrition-sensitive outcomes: The programme has no evidence of nutrition-sensitive outcomes.

This programme is therefore classified as not nutrition-sensitive .

Example of a nutrition-sensitive dominant programme

Linking Agribusiness and Nutrition – Development of a SUN Business Network (GAIN). Programme code GB-GOV-1- 203981.

All its actions contribute to nutrition-sensitive outcomes, including improved access to primary healthcare.

This programme is therefore classified as nutrition-sensitive dominant .

Example of a nutrition-sensitive partial programme

Livelihoods and Food Security Trust Fund for the rural poor and vulnerable in Burma. Programme code GB-GOV-1- 201239.

This programme meets all three of the criteria.

Not all of its actions contribute to nutrition-sensitive outcomes.

This programme is therefore classified as nutrition-sensitive partial .

Appendix 4: Programme classifications

Figure 17: Programme classification

Table 5: Nutrition-sensitive ODA by sector and purpose code, 2020, US$ millions

Table 6: Nutrition-sensitive ODA disbursements distribution among DAC CRS codes

| Sector and purpose code | Disbursements (US$ millions) |

|---|---|

| EMERGENCY RESPONSE | 555.0 |

| Emergency food assistance | 208.0 |

|

Material relief assistance and

services |

319.1 |

|

Relief co-ordination and support

services |

27.9 |

| BASIC HEALTH | 94.4 |

| Basic health care | 78.8 |

| COVID-19 control | 4.8 |

| Health education | 6.2 |

| Health personnel development | 3.8 |

| Infectious disease control | 0.8 |

| POPULATION POLICIES/PROGRAMMES AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH | 71.9 |

| Family planning | 1.3 |

|

Personnel development for population

and reproductive health |

0.0 |

| Reproductive health care | 70.5 |

| DEVELOPMENT: FOOD AID/ FOOD SECURITY ASSISTANCE | 39.6 |

| Food assistance | 39.6 |

| OTHER SOCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE AND SERVICES | 38.0 |

| Disaster risk reduction | 0.1 |

| Social protection | 37.8 |

| OTHERS | 180.7 |

| TOTAL | 979.5 |

Notes: US$ millions, 2020 prices.

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on DAC CRS data.

Appendix 6: Nutrition ODA by recipient

| Sector | Bilateral ODA (ODA disbursements, US$ millions) | Nutrition-sensitive ODA (ODA disbursements, US$ millions) | Nutrition-sensitive ODA as a proportion of total purpose code ODA (%) | Nutrition-sensitive ODA as a proportion of total nutrition-sensitive ODA (%) | Nutrition-sensitive ODA as a proportion of total bilateral ODA (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Material

relief assistance and services |

861.7 | 319.1 | 37.0% | 32.6% | 2.7% |

|

Emergency

food assistance |

215.8 | 208.0 | 96.4% | 21.2% | 1.8% |

|

Basic

health care |

94.2 | 78.8 | 83.6% | 8.0% | 0.7% |

|

Reproductive

health care |

91.7 | 70.5 | 76.9% | 7.2% | 0.6% |

|

Food

assistance |

93.8 | 39.6 | 42.2% | 4.0% | 0.3% |

| Social protection | 199.8 | 37.8 | 18.9% | 3.9% | 0.3% |

|

Primary

education |

243.2 | 31.7 | 13.0% | 3.2% | 0.3% |

|

Public

sector policy and administrative management |

206.1 | 28.9 | 14.0% | 2.9% | 0.2% |

|

Relief

co-ordination and support services |

50.4 | 27.9 | 55.4% | 2.8% | 0.2% |

|

Agricultural

research |

47.8 | 20.0 | 41.9% | 2.0% | 0.2% |

|

Multi-hazard

response preparedness |

90.2 | 18.6 | 20.7% | 1.9% | 0.2% |

|

Health

policy and administrative management |

48.6 | 17.0 | 35.1% | 1.7% | 0.1% |

|

Sectors

not specified |

4752.4 | 12.6 | 0.3% | 1.3% | 0.1% |

|

Basic drinking

water supply and basic sanitation |

32.8 | 9.8 | 29.8% | 1.0% | 0.1% |

|

Multisector

aid |

153.1 | 9.2 | 6.0% | 0.9% | 0.1% |

|

Agricultural

development |

56.4 | 8.5 | 15.0% | 0.9% | 0.1% |

|

Health

education |

9.9 | 6.2 | 62.7% | 0.6% | 0.1% |

|

Environmental

policy and administrative management |

53.6 | 5.6 | 10.5% | 0.6% | 0.05% |

|

COVID-19

control |

378.6 | 4.8 | 1.3% | 0.5% | 0.04% |

|

Health

personnel development |

3.8 | 3.8 | 100.0% | 0.4% | 0.03% |

|

Immediate

post-emergency reconstruction and rehabilitation |

21.0 | 3.5 | 16.5% | 0.4% | 0.03% |

|

Facilitation

of orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility |

58.3 | 3.3 | 5.7% | 0.3% | 0.03% |

|

Research/scientific

institutions |

135.1 | 2.2 | 1.7% | 0.2% | 0.02% |

|

Small

and medium-sized enterprises (SME) development |

71.1 | 1.8 | 2.5% | 0.2% | 0.02% |

|

Ending violence

against women and girls |

22.0 | 1.6 | 7.3% | 0.2% | 0.01% |

|

Road

transport |

19.1 | 1.6 | 8.4% | 0.2% | 0.01% |

|

Basic

sanitation |

6.6 | 1.3 | 20.0% | 0.1% | 0.01% |

|

Family

planning |

197.8 | 1.3 | 0.6% | 0.1% | 0.01% |

|

Environmental

research |

36.6 | 1.2 | 3.4% | 0.1% | 0.01% |

|

Infectious

disease control |

185.6 | 0.8 | 0.4% | 0.1% | 0.01% |

|

Security

system management and reform |

24.5 | 0.6 | 2.5% | 0.1% | 0.01% |

|

Basic

drinking water supply |

23.9 | 0.5 | 2.2% | 0.1% | 0.005% |

|

Human

rights |

22.5 | 0.3 | 1.4% | 0.03% | 0.003% |

|

Medical

research |

184.2 | 0.2 | 0.1% | 0.02% | 0.002% |

|

Water

sector policy and administrative management |

9.8 | 0.2 | 1.6% | 0.02% | 0.001% |

|

Disaster

risk reduction |

0.8 | 0.1 | 18.1% | 0.01% | 0.001% |

|

Democratic

participation and civil society |

72.3 | 0.1 | 0.2% | 0.01% | 0.001% |

|

Public

finance management (PFM) |

51.8 | 0.1 | 0.2% | 0.01% | 0.001% |

|

Construction

policy and administrative management |

1.6 | 0.1 | 7.2% | 0.01% | 0.001% |

|

Personnel

development for population and reproductive health |

5.8 | 0.05 | 0.8% | 0.005% | 0.0004% |

|

Agricultural

policy and administrative management |

2.5 | 0.03 | 1.3% | 0.003% | 0.0003% |

|

Financial

policy and administrative management |

870.1 | 0.02 | 0.003% | 0.003% | 0.0002% |

| TOTAL | 11750.0 | 979.5 |

Notes: Ordered by nutrition-sensitive ODA disbursements. US$ millions, 2020 prices. The total and relative shares refer to bilateral ODA to all sectors, including those not displayed in the table.

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on DAC CRS data.

Table 7: FCDO nutrition-related ODA by country and category, 2020, US$ millions

Appendix 7: Abbreviations

| Country | Nutrition-sensitive | Nutrition-specific | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yemen | 178.1 | 178.1 | |

| Bangladesh | 76.7 | 6.3 | 82.9 |

| South Sudan | 64.3 | 13.9 | 78.2 |

| Zimbabwe | 67.2 | 6.2 | 73.4 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 57.4 | 1.7 | 59.1 |

| Ethiopia | 56.8 | 56.8 | |

| Somalia | 49.0 | 5.0 | 54.0 |

| Sudan | 47.3 | 6.2 | 53.5 |

| Afghanistan | 45.7 | 45.7 | |

| Nigeria | 38.5 | 7.1 | 45.6 |

| Myanmar | 31.6 | 0.7 | 32.3 |

| Uganda | 29.1 | 2.8 | 31.9 |

| Central African Republic | 20.7 | 20.7 | |

| Venezuela | 19.9 | 19.9 | |

| Pakistan | 8.0 | 9.6 | 17.6 |

| Cameroon | 15.0 | 15.0 | |

| Kenya | 6.6 | 7.6 | 14.1 |

| Lebanon | 12.3 | 12.3 | |

| Mozambique | 6.7 | 5.6 | 12.3 |

| Malawi | 11.2 | 11.2 | |

| Nepal | 9.8 | 9.8 | |

| Sierra Leone | 8.2 | 8.2 | |

| Tanzania | 4.6 | 3.3 | 7.9 |

| Zambia | 1.8 | 3.7 | 5.6 |

| Rwanda | 3.8 | 0.8 | 4.7 |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 4.2 | 4.2 | |

| Chad | 2.4 | 2.4 | |

| West Bank and Gaza Strip | 1.6 | 1.6 | |

| Eritrea | 0.4 | 1.1 | 1.5 |

| Burundi | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| India | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Liberia | 0.1 | 0.1 |

Notes: US$ millions, 2020 prices.

Source: Development Initiatives’ calculations based on DAC CRS data.

Appendix 7: Abbreviations

Appendix 8: References

Development Initiatives, 2014. DFID’s aid spending for nutrition: 2010–2012. Available at: /resources/dfids-aid-spending-nutrition-2010-2012

Development Initiatives, 2015. DFID’s aid spending for nutrition: 2013. Available at: http://devinit.org/post/DFIDs-aid-spending-for-nutrition-2013

Development Initiatives, 2016. DFID’s aid spending for nutrition: 2014. Available at: http://devinit.org/post/DFIDs-aid-spending-for-nutrition-2014

Development Initiatives, 2017. DFID’s aid spending for nutrition: 2015. Available at: /resources/dfids-aid-spending-nutrition-2015

Development Initiatives, 2018. DFID’s aid spending for nutrition: 2016. Available at: http://devinit.org/post/DFIDs-aid-spending-nutrition-2016

Development Initiatives, 2019. DFID’s aid spending for nutrition: 2017. Available at: http://devinit.org/post/DFIDs-aid-spending-nutrition-2017

Development Initiatives, 2020. DFID’s aid spending for nutrition: 2018. Available at: /resources/DFIDs-aid-spending-for-nutrition-2018

Development Initiatives, 2021. FCDO’s aid spending for nutrition: 2019. Available at: /media/documents/FCDOs_Aid_Spending_for_Nutrition_2019.pdf

Development Initiatives, 2020. 2020 Global Nutrition Report: Action on equity to end malnutrition. Bristol, UK: Development Initiatives. Available at: https://globalnutritionreport.org/reports/2020-global-nutrition-report/

OECD, 2016. Handbook on the OECD-DAC Gender Equality Policy Marker. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/dac/gender-development/Handbook-OECD-DAC-Gender-Equality-Policy-Marker.pdf

OECD, 2018. Purpose Codes: sector classification. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/development/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/purposecodessectorclassification.htm

OECD, 2020. DAC and CRS code lists. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/dacandcrscodelists.htm

SUN Donor Network, 2013. Methodology and Guidance Note to Track Global Investments in Nutrition. Available at: http://scalingupnutrition.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/RESOURCE_TRACKING_METHODOLOGY_SUN_DONOR_NETWORK.pdf

World Health Organization, 2014. Comprehensive implementation plan on maternal, infant and young child nutrition. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/113048/WHO_NMH_NHD_14.1_eng.pdf

Appendix 9: About this report

About TASC

Technical Assistance to Strengthen Capabilities (TASC) is part of the broader Technical Assistance for Nutrition (TAN) Programme, funded by UK Aid, which is a mechanism to provide technical assistance to Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) country governments and build capacities toward advancing multi-sector nutrition agendas, in line with the SUN Movement principles and roadmap.

The objective of the TASC Project is to provide:

- Technical assistance to Governments in the SUN Movement and to the SUN Movement secretariat (SMS) to catalyse country efforts to scale up nutrition impact (Component 1) in 60+ SUN Movement countries.

- Technical assistance to the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) to maximise the quality and effectiveness of its nutrition-related policy and programmes, to support evidence generation and lesson learning and to develop nutrition capacity (Component 2)

TASC Partners

Contact

DAI Global UK Ltd | Registered in England and Wales No. 01858644 | Address: 3rd Floor Block C Westside, London Road, Apsley, HP3 9TD, United Kingdom

DAI Global Health Ltd | Registered in England and Wales No. 01858644 | Address: 3rd Floor Block C Westside, London Road, Apsley, HP3 9TD, United Kingdom

DAI Global Belgium SRL | Registered in Belgium No. 0659684132 | Address: Avenue de l'Yser 4, 1040 Brussels, Belgium

Project Director: Paula Quigley, Paula_Quigley@dai.com

Project Manager: Hanna Ivascu, Hanna_Ivascu@dai.com

About This Publication

This document was produced through support provided by UK aid and the UK Government; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK Government’s official policies.

Notes

-

1

SDN, 2013. Methodology and Guidance Note to Track Global Investments in Nutrition. Available at: http://docs.scalingupnutrition.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/RESOURCE_TRACKING_METHODOLOGY_SUN_DONOR_NETWORK.pdfReturn to source text

-

2

The OECD defines sectors as the "specific area of the recipient’s economic or social structure is the transfer intended to foster". www.oecd.org/dac/stats/purposecodessectorclassification.htm (accessed 14/05/2021).Return to source text

Related content

Donors at the triple nexus

DI Senior Policy & Engagement Advisor Sarah Dalrymple presents some of our recent analysis into how donors like Sweden and the UK are approaching the triple nexus between humanitarian, development and peace approaches in crisis contexts.

Implications of coronavirus on financing for sustainable development

DI Executive Director Harpinder Collacott summarises the possible impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on global development - including projections for extreme poverty, the future of different forms of financing, and the countries likely to be most impacted.

What do emerging trends in development finance mean for crisis actors?

DI's webinar ‘What do emerging trends in development finance mean for crisis actors?’ gives crisis actors key information on development finance to better understand what it means for them.