Funding for gender-relevant humanitarian response: Chapter 2

Gender-relevant international humanitarian assistance

DownloadsTotal gender-relevant international humanitarian funding

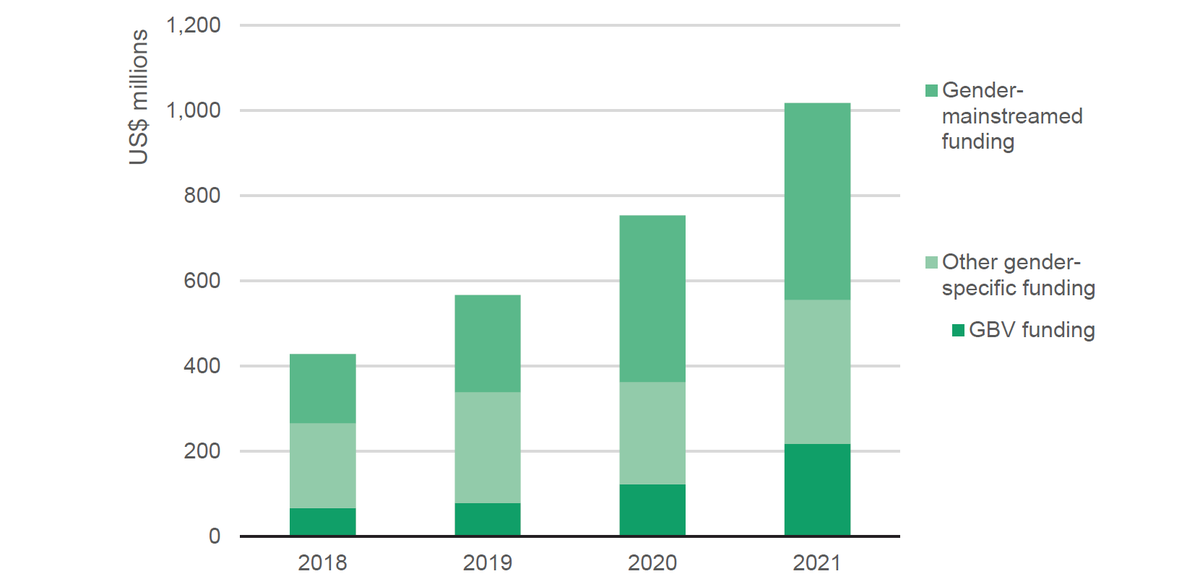

Figure 2.1: Gender-specific international humanitarian funding doubled between 2018 and 2021

Global volumes of gender-relevant international humanitarian funding, 2018–2021, split by GBV, other gender-specific and gender-mainstreamed funding

A stacked column chart showing the breakdown of GBV, other gender-specific and gender-mainstreamed funding from 2018 to 2021 in US$ millions.

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBV funding | 67.3 | 78.4 | 122.8 | 217.7 |

|

Other gender-specific

funding |

199.1 | 260.7 | 240.0 | 337.1 |

|

Gender-mainstreamed

funding |

162.3 | 227.4 | 390.4 | 462.4 |

| Total gender relevant | 428.7 | 566.4 | 753.3 | 1,017.2 |

Source: Development Initiatives based on the UN OCHA Financial Tracking Service (FTS).

Notes: Data is in constant 2019 prices and US$ millions. Data was downloaded in January 2022. 2021 figures may be incomplete and subject to update. GBV: gender-based violence.

Gender-specific international humanitarian assistance has grown significantly since 2018. A number of factors, including improved reporting, may explain the increase in funding evident in the reported data.

- In 2021, a total of US$555 million of gender-specific international humanitarian assistance was provided. This represents consistent growth , with the volume of gender-specific funding more than doubling (a rise of 108%) from US$266 million in 2018.

- The pace of growth in gender-specific funding has increased between 2020 and 2021 , with funding rising by US$192 million (53% growth).

- Most gender-specific international humanitarian assistance (85%) is being channelled to countries experiencing protracted crisis, [1] where humanitarian need has been consistently high for a number of years.

- In addition to this gender-specific funding, other gender-relevant funding is being provided through programmes where gender is included as a mainstreamed component. In 2021, these programmes totalled US$462 million, though the proportion of this funding allocated to gender-related interventions is not known and will vary between programmes.

- Overall, programmes totalling US$1,017 million included some degree of gender-relevant international humanitarian assistance in 2021 , more than twice the volume reported in 2018 (US$429 million).

Behind these aggregate figures there are some large individual funding allocations. The single largest funding flow in 2021 was from the United States’ Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (BPRM), which contributed over US$100 million through cash-based programming that was seen as gender-relevant towards the regional Syrian refugee response.

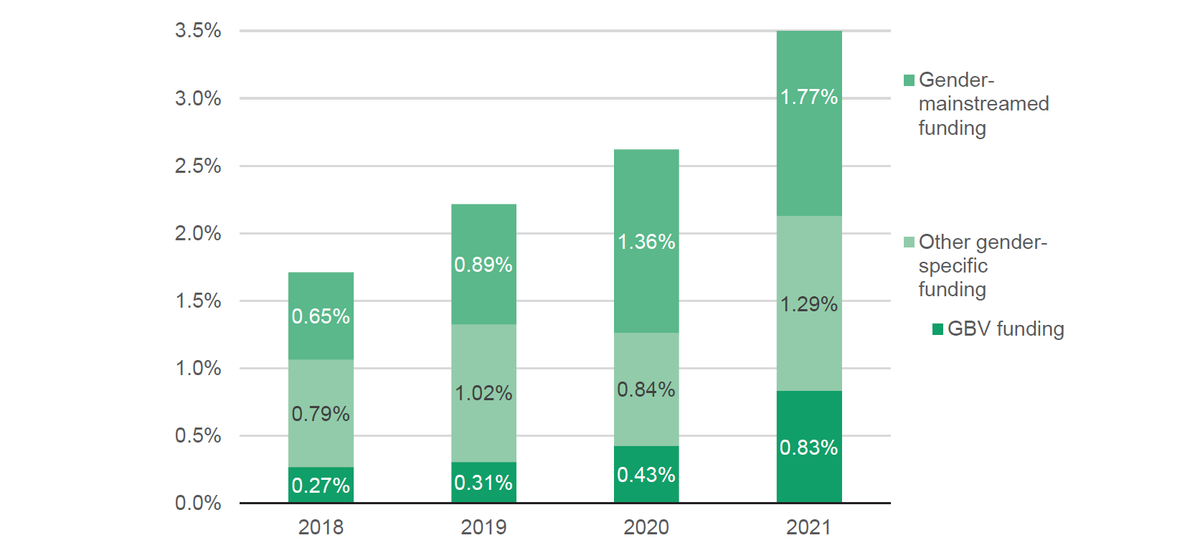

Figure 2.2: Despite increases between 2018 and 2021, gender-relevant funding remains a very small proportion of total international humanitarian assistance

Proportion of gender-relevant funding out of total international humanitarian assistance, 2018–2021

A stacked percentage column chart showing the breakdown of GBV, other gender-specific and gender-mainstreamed funding from 2018-2021.

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBV funding | 0.27% | 0.31% | 0.43% | 0.83% |

|

Other gender-specific

funding |

0.79% | 1.02% | 0.84% | 1.29% |

|

Gender-mainstreamed

funding |

0.65% | 0.89% | 1.36% | 1.77% |

Source: Development Initiatives based on the UN OCHA Financial Tracking Service (FTS).

Notes: Data is in constant 2019 prices and US$ millions. Data was downloaded in January 2022. 2021 figures may be incomplete and subject to update. GBV: gender-based violence.

Volumes of gender-specific international humanitarian assistance have increased more quickly than total international humanitarian assistance, with the proportion of total assistance provided that was gender specific growing rapidly between 2018 and 2021.

- Between 2018 and 2021, total international humanitarian assistance from governments and EU institutions [2] reported to the UN OCHA’s FTS increased by 4%. This compares to growth in total gender-specific humanitarian assistance over the same period of 108%.

- Gender-specific funding has grown year on year between 2018 and 2021, despite total international humanitarian assistance decreasing by 9% between 2020 and 2021, according to data reported to UN OCHA’s FTS. [3]

- Including the value of programmes within which elements of gender have been mainstreamed to a greater or lesser extent, the total gender-relevant assistance grew by 137%.

While the total volume of gender-specific humanitarian assistance has grown, in 2021 it still accounted for a small proportion of total international humanitarian assistance.

- With increasing volumes of gender-specific assistance provided, the proportion of total assistance that was gender-specific has risen from 1.1% in 2018 to 2.1% in 2021 .

- Within gender-specific funding, GBV funding represents an increasing but very small proportion of total assistance , growing from 0.27% in 2018 to 0.43% in 2020. In 2021, the share of GBV funding doubled to 0.83%.

- Between 2018 and 2021, gender-specific funding accounted for a decreasing share of total funding identified as gender-relevant, falling from 62% in 2018 to 55% in 2021, having dipped to a low of 48% in 2020.

A number of factors may be behind the overall growth in gender-specific humanitarian assistance evident in the reported UN OCHA FTS data. As described above, promoting gender equality in humanitarian responses has received increasing attention in policy discussions, resulting in rhetorical and pledged commitments of greater financing. Issues of GBV have received particular attention, driven in part by their prioritisation by former UN Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark Lowcock, who sent a personal message to all UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinators in late 2019 declaring that tackling GBV was one of his top four priority areas. The growth in gender-specific funding suggested by our analysis may also in part be explained by increased reporting of gender-relevant projects, with the increased profile of GBV and gender in humanitarian responses encouraging reporters to capture gender-related responses more regularly in the data and project descriptions they provide to UN OCHA’s FTS.

Despite the increased profile of gender-related issues within humanitarian policy and the rising financial commitments to advance gender equality and women’s economic empowerment, global efforts to protect women and girls in emergencies are perceived by many to have fallen short during Covid-19 . Key informant interviews concurred that the response to the Covid-19 pandemic demonstrated, once again, how difficult it is to mobilise humanitarian funding for gender-related needs. A UN representative stressed that the Global Humanitarian Response Plan (GHRP) to Covid-19 was ‘gender blind’ at the time it was launched, meaning it had a narrow focus on protection and GBV [4] , although this was acknowledged to have improved as the response developed. The UN representative elaborated that the original GHRP failed to consider women’s vital community mobilisation role, the specific impacts on women’s economic situation and also failed to consult with women representatives on their specific needs. A donor representative with expertise on GBV admitted that it was harder to advocate internally for GBV prevention during Covid-19 as it was not perceived as life-saving aid by some policymakers, despite recognition of the GBV shadow pandemic. The lack of sufficient prioritisation and consequent action on GBV within humanitarian responses spurred more than 500 actors (donors and NGOs) to write to the then UN Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark Lowcock, in June 2020 to call for more funding for GBV in the Covid-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan. This action speaks to the underlying challenge of prioritising gender in humanitarian responses, a difficulty well covered in the literature on gender financing, which points to the need to constantly present evidence to make a case for the importance of gender-related funding in emergency responses.

Funding diverted away from gender-relevant responses

The available data on gender-relevant programming allows for aggregate analysis of the volumes of funding allocated. However, from the available data it is not possible to see where funding may have been cut or re-allocated away from gender-relevant interventions, or where the original intent of a programme to improve gender equality or empower women and girls may have been diluted. In the absence of this quantitative data, perspectives drawn from key informant interviews found a common perception that resources for GBV and broader gender-relevant programming were diverted to respond to other needs arising from the Covid-19 pandemic. As research by UN Women and UNFPA concluded: “feedback provided during the consultation process… highlighted that programming for women and girls is often one of the first types of programming to be cut”. [5] Findings from a 2021 survey of women’s rights organisations conducted by Oxfam concurred, noting that these frontline organisations were often the first to suffer cuts to funding during the Covid-19 pandemic. [6] An INGO gender expert interviewed for this study stated “What we saw was a diversion of funds towards COVID. Particularly [when] looking at some of the longer-term programming on eliminating child and early marriage or sexual and reproductive health rights, [these] shifted towards the emergency response.” In other cases, funding was delivered to meet the needs of women and girls, but its gender-specific impact was considered less. “Many of them got funding diverted. You were going to do some women improvement activities, [but instead] you take this money and you buy masks and gel – which is health, and is okay, but it’s not the same impact on women’s lives and changing the social dynamics”, stated one interviewee.

According to interviewees for this study, the best chance for gender-related projects – whether targeted or mainstreamed – to survive diversion or cancelling during the pandemic was to already have integrated a gender component before the pandemic arrived. UNICEF’s cash programmes, for instance, integrated gender and GBV into humanitarian cash and social protection activities before Covid-19, so their cash social protection activities were more likely to remain relevant to their original purpose in 2020 and 2021, despite the rising needs of the health emergency. In the words of a gender programming expert “in the work we’ve been doing around shock-responsive social protection in the context of Covid, one of the key things that is being said is that [before the] pandemic if a social protection programme or system didn’t have a strong gender element to it, it was really unlikely that in the [new] context (…) it would then have a new gender-responsive component or a very strong gender component”.

Funding flexibility

Consistent with findings on wider humanitarian responses not focused on gender-related issues, many interviewees highlighted the importance of receiving flexible, lightly earmarked funding (with no, or only limited, restrictions on use, for instance, for a particular strategic theme or within a geographic region) to enable appropriate and timely responses. This was considered particularly important in the context of a fast-evolving emergency. In this regard, guidance on funding flexibility developed by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee was highlighted as an important resource to inform practice. [7] The importance of the ‘quality’ of funding, in terms of duration, predictability and flexibility, were highlighted in relation to funding reaching local and national actors, explored in more detail in the sub-section Gender-specific funding for local and national organisations . Similarly, the use of cash-based and voucher assistance was repeatedly mentioned by interviewees as the most efficient mechanism to deliver assistance for women in the context of lockdowns. [8] See Box 2.1 and Box 2.2 for examples of good practice in delivering gender-relevant funding and programming.

Box 2.1

Good practice in delivering gender-relevant funding

Rapid-reaction, gender-focused funds were mentioned by our key informants as the most effective mechanisms to tackle the rise in gender needs during Covid-19. One example of this was the Global Resilience Fund for Girls and Young Women, a partnership between women’s funds, private foundations, NGOs, multilaterals and bilateral agencies, which provided flexible rapid response grants of up to US$5,000 to resource girls’ and young women’s activism through the crisis. [9] The UN Trust Fund to Eliminate Violence against Women also funded activities that offered core support to women’s organisations and created a new GBV-focused funding window for the Covid-19 response. [10] Additionally, Mama Cash, an international women's fund, established the Recovery & Resilience Fund to boost their existing partner grants. This was funded through budget reallocations and donor support. [11] While examples of good practice, these initiatives account for a very small proportion of total funding.

Box 2.2

Promoting collaboration in gender-relevant programming

The pandemic provided opportunities for greater collaboration around improving gender programming and addressing knowledge gaps. [12] One example was the creation of a helpline platform called SPACE, which provided online expert advice on social protection in response to the Covid-19 crisis, funded by the UK, Germany and Australia. One of its members highlighted the opportunity of having some of the best gender experts working together virtually in the context of Covid-19 and how it was an initiative that helped donors navigate difficult decisions about whether to expand coverage or to improve existing programmes, for example around cash transfers, and to consider the gender implications of these decisions. Having a strong cohort of gender and social inclusion experts allowed the team to provide expert support to mainstream gender issues around the response in over 40 countries.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and UN Women’s Global Gender Response Tracker, which monitors responses taken by governments worldwide to tackle the pandemic, also created national gender taskforces worldwide to promote accountability around gender policy. [13] While a positive initiative, on average only 24% of the participants were women. [14]

Humanitarian funding for GBV prevention and response

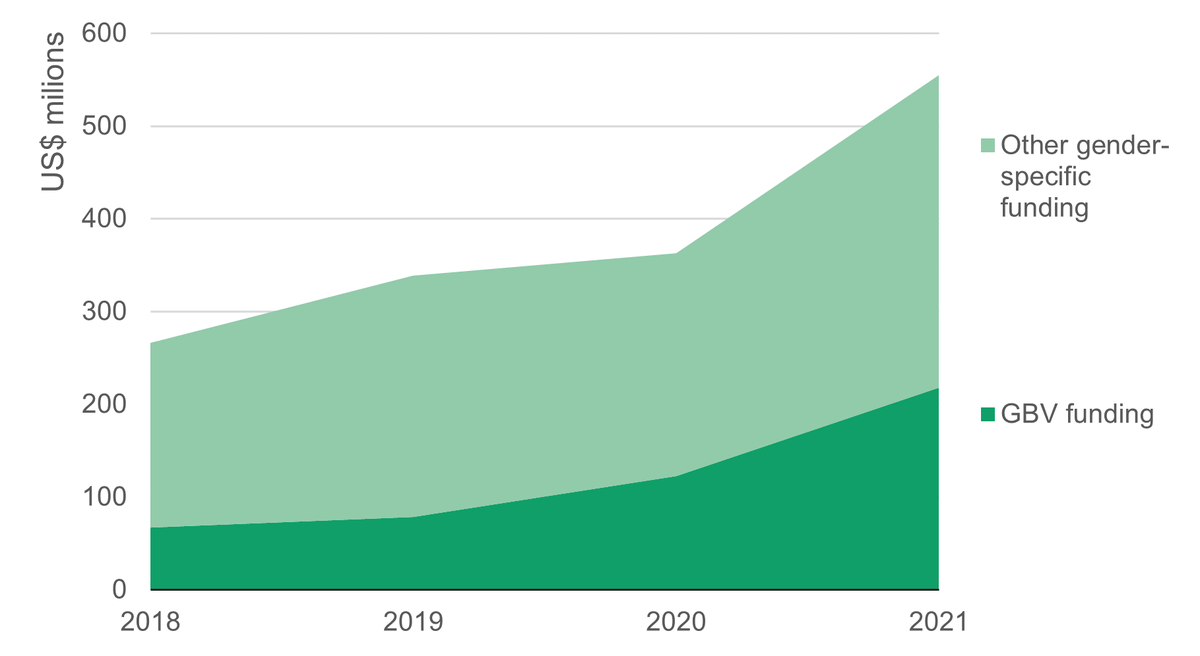

Figure 2.3: Humanitarian GBV funding more than tripled between 2018 and 2021

Humanitarian GBV funding and all other gender-specific funding, 2018–2021

An area chart showing the breakdown of GBV and other gender-specific funding from 2018 to 2021 in US$ millions.

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBV funding | 67.3 | 78.4 | 122.8 | 217.7 |

|

Other gender-specific

funding |

199.1 | 260.7 | 240.0 | 337.1 |

Source: Development Initiatives based on the UN OCHA Financial Tracking Service (FTS).

Notes: Data is in constant 2019 prices and US$ millions. Data was downloaded in January 2022. 2021 figures may be incomplete and are subject to update. GBV funding figures may differ slightly from those reported on the FTS website as these include funding outside appeals while the FTS only accounts for flows within a humanitarian response plan. GBV: gender-based violence.

GBV is one Area of Responsibility (AoR) under the Global Protection Cluster, focusing on efforts to prevent, mitigate risk and respond to all forms of GBV in humanitarian responses. [15] As discussed above, one of the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic has been a significant increase in the prevalence rates of GBV. Analysis of funding for GBV indicates that more assistance has been reported as allocated to GBV responses, but that funding has not kept pace with increasing needs .

- Total international humanitarian assistance for GBV reported under the Global Protection Cluster has more than tripled between 2018 and 2021, rising from US$67 million to US$218 million.

- The increases in GBV funding have outpaced rises in other gender-specific funding , which in comparison grew by just over two-thirds (69%) over the same period.

- The pace of growth in GBV funding has increased between 2018 and 2021, with annual increases of 16%, 57% and 77%.

- In 2021, funding for GBV accounted for 39% of total gender-specific funding and 21% of total gender-relevant funding.

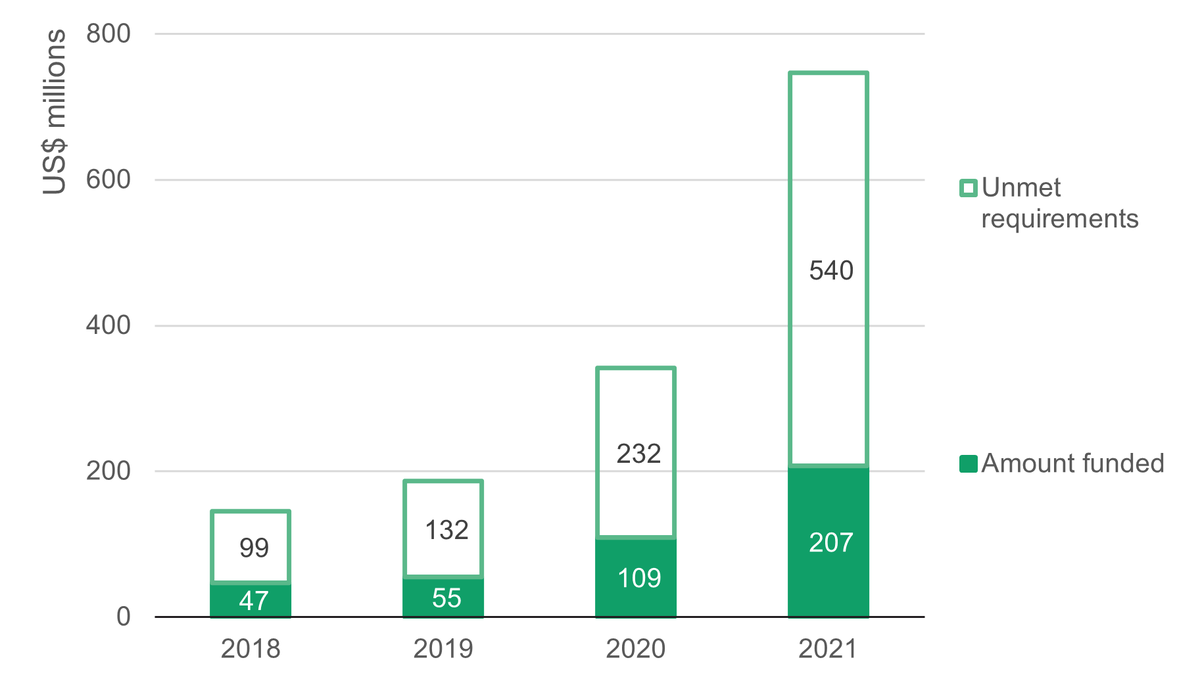

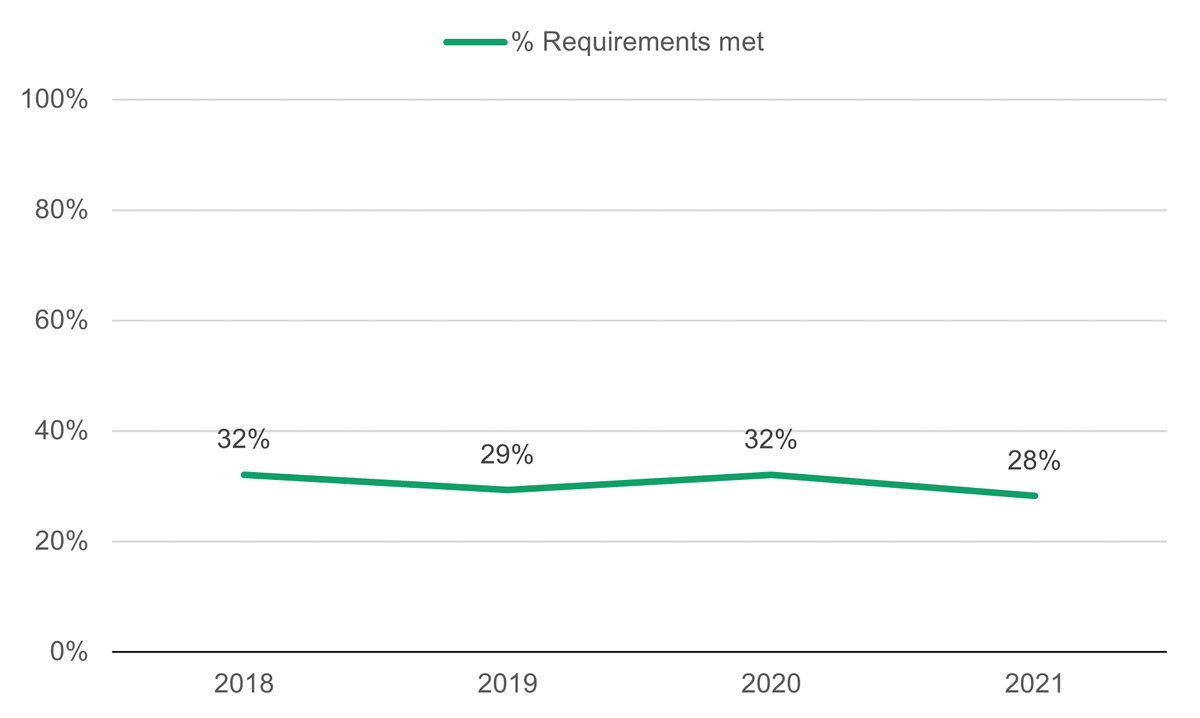

Figure 2.4: Between 2018 and 2021 just under a third of GBV funding requirements were met each year as funding and needs grew sharply

GBV requirements and funding, 2018–2021, global coverage

A stacked column chart showing the amounts funded and unmet requirements of GBV funding requirements from 2018 to 2021 in US$ millions.

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount funded | 47 | 55 | 109 | 207 |

| Unmet requirements | 99 | 132 | 232 | 540 |

|

% Requirements

met |

32% | 29% | 32% | 28% |

Proportion of requirements met, 2018–2021

A line chart showing the % of GBV funding requirements met from 2018 to 2021.

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount funded | 47 | 55 | 109 | 207 |

| Unmet requirements | 99 | 132 | 232 | 540 |

|

% Requirements

met |

32% | 29% | 32% | 28% |

Source: UN OCHA Financial Tracking Service (FTS).

Notes: Data is in current prices and US$ millions. Data here reflects funding figures shown on FTS appeals pages, therefore only includes flows reported under a humanitarian response plan to the GBV Area of Responsibility. GBV: gender-based violence.

Funding for GBV, as a proportion of GBV requirements, has been consistently lower than that the average received by other sectors within UN appeals.

- Between 2018 and 2021, the proportion of funding requirements met for the GBV AoR remained relatively stable, fluctuating between a low of 28% in 2021 and a high of 32% in 2018 and 2020 .

- However, these proportions are lower than the coverage of total appeal requirements over the same period, which have fluctuated between a high of 63% in 2019 and lows of 50% in 2020 and 2021.

While underfunding for all appeal requirements has worsened between 2018 and 2021, GBV underfunding has remained stable .

- The relative degree of underfunding for GBV, in the context of total appeal funding , has therefore improved slightly . In 2018, 61% of total appeal requirements were met, with 32% of GBV funding requirements fulfilled. In 2021, funding for total appeal requirements fell to 50%, while GBV requirements received just 28%.

Between 2018 and 2021 the Global Protection Cluster has suffered growing shortfalls in funding compared with its requirements.

- In 2021, the proportion of funding requirements met for the Global Protection Cluster as a whole more than halved, from 42% in 2020 to just 19%.

Compared with other AoRs within the Global Protection Cluster, the funding coverage for GBV has, relatively speaking, improved.

- Between 2018 and 2020, the GBV AoR had a lower proportion of its funding requirements met than the average for the Global Protection Cluster.

- However, in 2021 GBV requirements were fulfilled at a higher level, 28%, than the average for the Protection Cluster, just 19%.

Donors of gender-specific humanitarian assistance

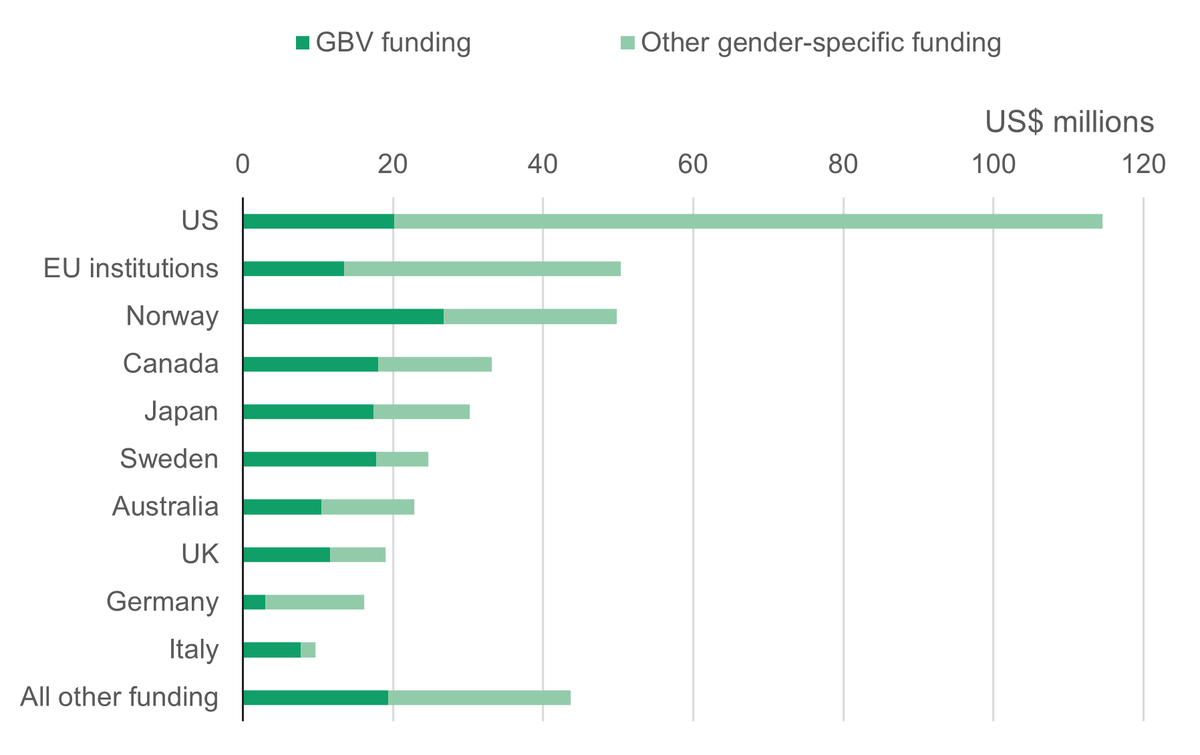

Figure 2.5: Gender financing is concentrated amongst the 10 largest donors

10 largest donors by volume of gender-specific international humanitarian assistance (GBV and other gender-specific funding), 2021

A stacked bar chart showing the breakdown of GBV and other gender-specific funding of the 10 largest donors (US, EU institutions, Norway, Canada, Japan, Sweden, Australia, UK, Germany, Italy) and all other funding in 2021 in US$ millions.

| Donor | GBV funding | Other gender-specific funding |

|---|---|---|

| US | 20.1 | 94.4 |

| EU institutions | 13.5 | 36.9 |

| Norway | 26.8 | 23.0 |

| Canada | 18.0 | 15.1 |

| Japan | 17.4 | 12.9 |

| Sweden | 17.8 | 6.9 |

| Australia | 10.4 | 12.4 |

| UK | 11.7 | 7.4 |

| Germany | 3.0 | 13.2 |

| Italy | 7.7 | 1.9 |

| All other funding | 19.4 | 24.3 |

Source: Development Initiatives based on the UN OCHA Financial Tracking Service (FTS).

Notes: Data is in constant 2019 prices and US$ millions. Data was downloaded in January 2022. 2021 figures may be incomplete and are subject to update. GBV: gender-based violence. EU institutions includes funding from the European Commission's Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection Department, European Commission’s Directorate-General for International Partnerships (formerly EuropeAid DEVCO) and European Commission’s EU Facility for Refugees in Turkey.

Total gender-specific international humanitarian assistance is highly concentrated among the 10 largest donors, with the United States (US) the largest donor in 2021.

- Over the period 2018 to 2021, 87% of all gender-specific international humanitarian assistance was provided by just 10 donors. In 2021, the degree of concentration intensified, with 89% of funding coming from the 10 largest donors .

- In 2021, the US provided US$115 million of gender-specific funding, accounting for 28% of total gender-specific assistance . Of this assistance just under a fifth (18%) was for GBV programming.

- EU institutions and Norway contributed the joint second largest volume of gender-specific assistance in 2021: US$50 million each. More than half of Norway’s funding (54%) was directed to GBV programming, making Norway’s US$26.8 million the single largest volume of funding for GBV of any donor .

- In 2021, Germany and the UK, the second and fourth largest bilateral donors of international assistance, were respectively the 9th and 8th largest contributors of gender-specific humanitarian funding.

Reported funding from donors identifiable as gender-specific since 2018 suggests that Norway, Canada and the EU have all notably increased the volume of gender-specific humanitarian assistance they provide.

- Norway’s allocations increased by 80% between 2019 and 2020 with volumes flatlining in 2021, while Canada’s contributions have grown year on year between 2018 to 2021, increasing by 169%.

- Funding from the EU increased by half (50%) between 2018 and 2021 to US$50 million.

- The well-reported reductions to the UK’s overall aid budget are evident in the halving (50%) of gender-specific international assistance in 2020 from 2019 volumes. However, in 2021, UK gender-specific contributions recovered slightly, growing by 15%.

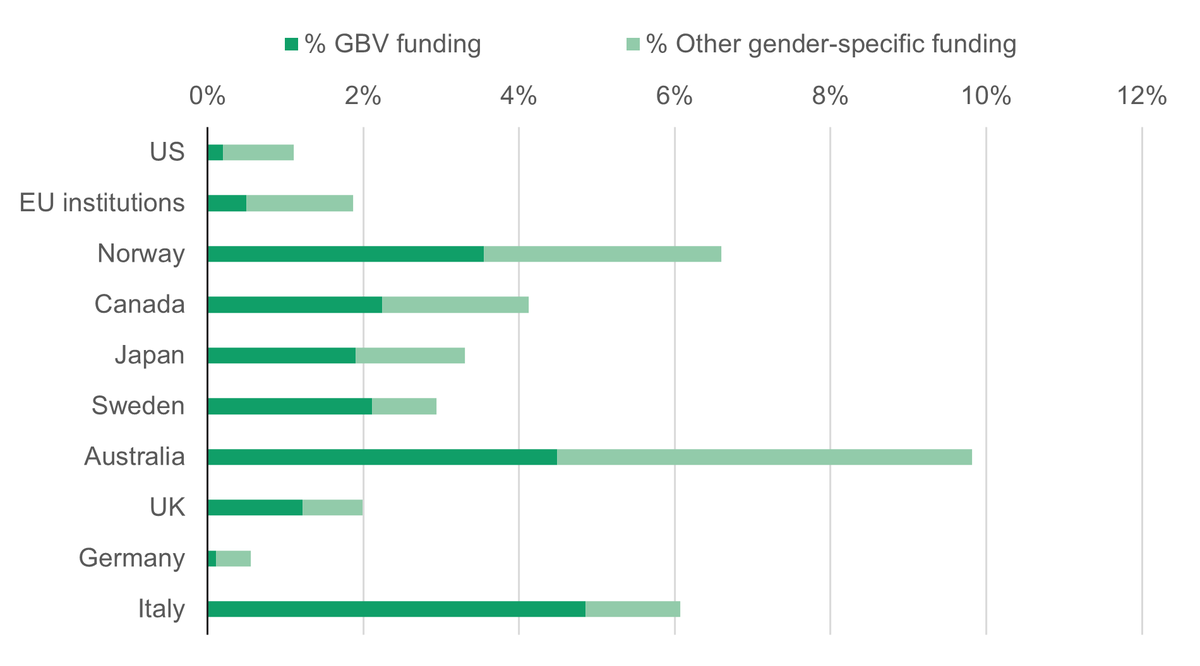

Figure 2.6: The proportion of total humanitarian funding provided for gender-relevant programmes varies greatly between donors

10 largest donors by % share of gender-specific funding out of total international humanitarian assistance, 2021

A stacked bar percentage chart showing the share of GBV and other gender-specific funding of each of the 10 largest donors (US, EU institutions, Norway, Canada, Japan, Sweden, Australia, UK, Germany, Italy) in 2021.

| Donor | % GBV funding | % Other gender-specific funding | % in 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| US | 0.2% | 0.9% | 1.1% |

| EU institutions | 0.5% | 1.4% | 1.9% |

| Norway | 3.5% | 3.0% | 6.6% |

| Canada | 2.2% | 1.9% | 4.1% |

| Japan | 1.9% | 1.4% | 3.3% |

| Sweden | 2.1% | 0.8% | 2.9% |

| Australia | 4.5% | 5.3% | 9.8% |

| UK | 1.2% | 0.8% | 2.0% |

| Germany | 0.1% | 0.5% | 0.6% |

| Italy | 4.9% | 1.2% | 6.1% |

Source: Development Initiatives based on the UN OCHA Financial Tracking Service (FTS).

Notes: Data is in constant 2019 prices and US$ millions. Data was downloaded in January 2022. 2021 figures may be incomplete and are subject to update. GBV: gender-based violence. EU institutions includes funding from the European Commission's Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection Department, European Commission’s Directorate-General for International Partnerships (formerly EuropeAid DEVCO) and European Commission’s EU Facility for Refugees in Turkey.

Analysing gender-specific international humanitarian assistance from donors as a proportion of the total funding they provide for all areas of humanitarian need gives an indication of the degree to which gender-specific interventions are prioritised by individual donors. In 2021, three donors provided more than 6% of their assistance for gender-specific programmes, while for the four largest donors of total international humanitarian assistance, 2% or less of their funding was identifiable as gender specific.

- In 2021, the donors providing the highest proportion of their humanitarian assistance for gender-specific programmes were Australia (9.8% as gender-specific), Norway (6.6%) and Italy (6.1%).

- The US, Germany, the EU and the UK – the four largest donors of total international humanitarian assistance and, in the case of the US, the largest donor by volume of gender-specific assistance – respectively provided 1.1%, 0.6%, 1.9% and 2.0% of their total humanitarian assistance for gender-specific programmes .

Recipients of gender-specific humanitarian assistance

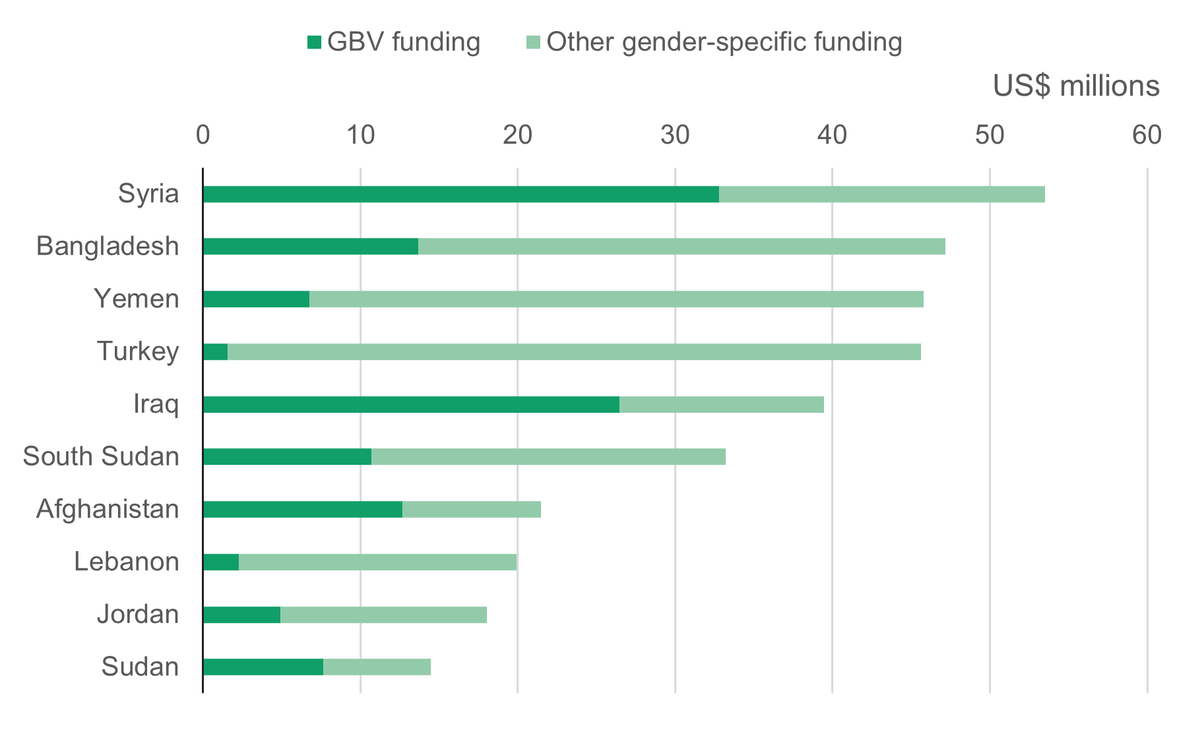

Figure 2.7: The proportion of gender-specific funding provided for GBV varies greatly between recipients

10 largest country recipients by volume of gender-specific international humanitarian assistance (GBV and other specific funding), 2021

A stacked bar chart showing the breakdown of GBV and other gender-specific funding that the 10 largest country recipients (Syria, Bangladesh, Yemen, Turkey, Iraq, South Sudan, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Jordan, Sudan) receive in 2021 in US$ millions.

| Recipient | GBV funding | Other gender-specific funding |

|---|---|---|

| Syria | 32.8 | 20.7 |

| Bangladesh | 13.7 | 33.5 |

| Yemen | 6.8 | 39.0 |

| Turkey | 1.6 | 44.1 |

| Iraq | 26.4 | 13.0 |

| South Sudan | 10.7 | 22.5 |

| Afghanistan | 12.7 | 8.8 |

| Lebanon | 2.3 | 17.6 |

| Jordan | 4.9 | 13.1 |

| Sudan | 7.6 | 6.9 |

Source: Development Initiatives based on the UN OCHA Financial Tracking Service (FTS).

Notes: Data is in constant 2019 prices and US$ millions. Data was downloaded in January 2022. 2021 figures may be incomplete and are subject to update. Totals only include international humanitarian assistance to the recipient country and exclude funding flows transferred within the country to avoid double counting of ‘internal’ FTS flows. GBV: gender-based violence.

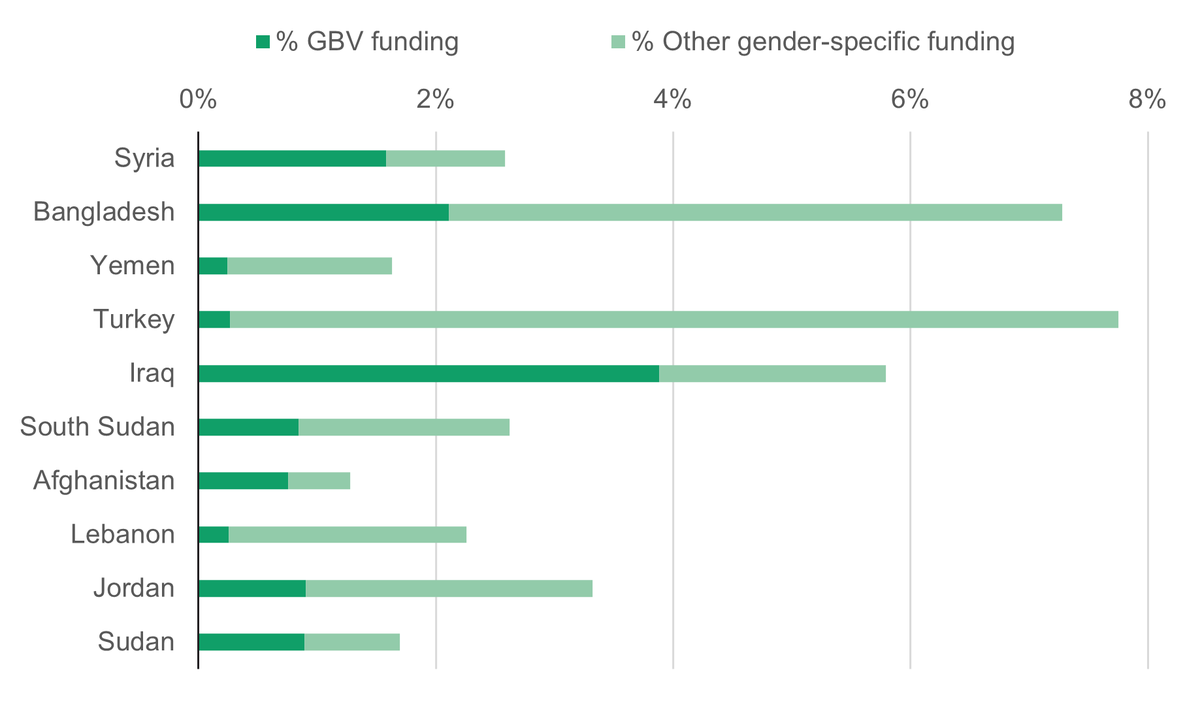

Figure 2.8: The proportion of total humanitarian assistance provided as gender-specific funding varies significantly between recipients

10 largest recipients by volume of gender-specific international humanitarian assistance by % share of gender-specific funding out of total assistance, 2021

A stacked percentage bar chart showing the proportion of GBV and other gender-specific funding out of the total IHA that the 10 largest recipients (Syria, Bangladesh, Yemen, Turkey, Iraq, South Sudan, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Jordan, Sudan) receive in 2021.

| Recipient | % GBV funding | % Other gender-specific funding | % in 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syria | 1.6% | 1.0% | 2.6% |

| Bangladesh | 2.1% | 5.2% | 7.3% |

| Yemen | 0.2% | 1.4% | 1.6% |

| Turkey | 0.3% | 7.5% | 7.8% |

| Iraq | 3.9% | 1.9% | 5.8% |

| South Sudan | 0.8% | 1.8% | 2.6% |

| Afghanistan | 0.8% | 0.5% | 1.3% |

| Lebanon | 0.3% | 2.0% | 2.3% |

| Jordan | 0.9% | 2.4% | 3.3% |

| Sudan | 0.9% | 0.8% | 1.7% |

Source: Development Initiatives based on the UN OCHA Financial Tracking Service (FTS).

Notes: Data is in constant 2019 prices and US$ millions. Data was downloaded in January 2022. 2021 figures may be incomplete and are subject to update. Totals only include international humanitarian assistance to the recipient country and exclude funding flows transferred within the country to avoid double counting of ‘internal’ FTS flows. GBV: gender-based violence.

Gender-specific international humanitarian assistance is concentrated in a small number of recipients. However, some countries received significantly more gender-specific funding as a share of total humanitarian assistance than others.

- In 2021, the three largest recipients of gender-specific international humanitarian assistance were Syria, Bangladesh and Yemen . These three countries received US$146 million of gender-specific assistance, just under a third (29%) of all allocated gender-specific funding.

- The 10 largest recipients of gender-specific funding in each year between 2018 and 2021 have accounted for 71% of all gender-specific assistance. This concentration of funding among a relatively small number of recipient countries mirrors trends in total international assistance for all humanitarian needs. [16]

- Of the total gender-specific funding received by individual recipients, the share of this funding directed for GBV varies greatly between countries. Turkey received just 3% for GBV programming in 2021, while Iraq received 67%. This fluctuation in GBV funding across countries might be due to different appeal funding mechanisms and a varying degree of considerations of GBV programming. The presence or absence of the Global Protection Cluster – GBV AoR in the global cluster setup or humanitarian country team in each country might also play a role, as more funding might be recorded where this formal structure exists to capture and report on GBV funding.

At the other end of the spectrum, the 10 countries receiving the smallest volume of gender-specific international humanitarian assistance were in total allocated US$19 million in 2021, compared to US$339 million received by the 10 largest recipients.

- The three smallest recipients of gender-relevant international humanitarian assistance were Kenya (US$0.6 million), Burundi (US$0.7 million) and Rwanda (US$1.2 million).

- These three countries received US$2.6 million of gender-specific assistance and also had some of the lowest percentage shares of gender-relevant assistance out of total funding: 0.4%, 0.9% and 4.3%, respectively.

Looking at the proportion of total international humanitarian assistance that was gender specific for each recipient gives some indication of the prioritisation of gender-focused interventions. Though the absence of data to quantify levels of need – except GBV needs that are specifically identified within the Global Protection Cluster GBV AoR for humanitarian response plans – means that assessing sufficiency and effective targeting is not possible. The reported data indicates a significant degree of variation between countries in the proportion of total assistance that is identifiable as gender specific.

- In three countries more than 5% of their total international humanitarian assistance was for gender-specific programming in 2021, with Turkey receiving 7.8% as gender specific, Bangladesh receiving 7.3% and Iraq receiving 5.8%.

- Gender-specific funding provided to Afghanistan, Yemen and Sudan accounted for much smaller proportions of total funding, at 1.3%, 1.6% and 1.7%, respectively.

- Over the period 2018 to 2021, the proportion of gender-specific funding received out of total assistance has varied notably in some countries. For instance, Turkey and Bangladesh have seen significant increases in their gender-specific funding out of total assistance from 2020 to 2021 (from 1.2% to 7.8% and from 1.8% to 7.3%, respectively). While Yemen, Iraq and Lebanon have seen steady growth over the period 2018 to 2021.

- Among the 10 smallest recipients, one country received more than 5% of their total international humanitarian assistance for gender-specific programming in 2021; this was Tanzania with 5.6%. For these 10 countries, the average of gender-specific funding out of the total assistance was 2.3%. This is lower than the average of 3.5% across all recipients of gender-specific humanitarian assistance.

Delivery channels for gender-specific humanitarian assistance

The majority of total international humanitarian assistance from public donors is provided to multilateral agencies. In 2020, two-thirds (66%) of total international assistance were provided to these agencies, with just under a fifth (18%) allocated directly to NGOs (primarily international organisations). [17] These allocation patterns have remained unchanged for the past five years.

Analysing gender-specific assistance illustrates that between 2018 and 2020 these trends for total assistance are replicated. Multilateral agencies received on average 60% of total gender-specific assistance during this period, while NGOs received on average 29%, a slightly higher proportion of funding than typical for total international humanitarian assistance. Reported funding for 2021, however, indicates a change in these patterns, with a higher proportion (82%) of gender-specific assistance channelled to multilateral agencies, with just 13% received directly by NGOs. As is the case for total international humanitarian assistance, comprehensive data is only available for the first recipients of funding, and so how and in what volumes funding is subsequently passed on to other implementers cannot be seen.

Gender-specific funding for local and national organisations

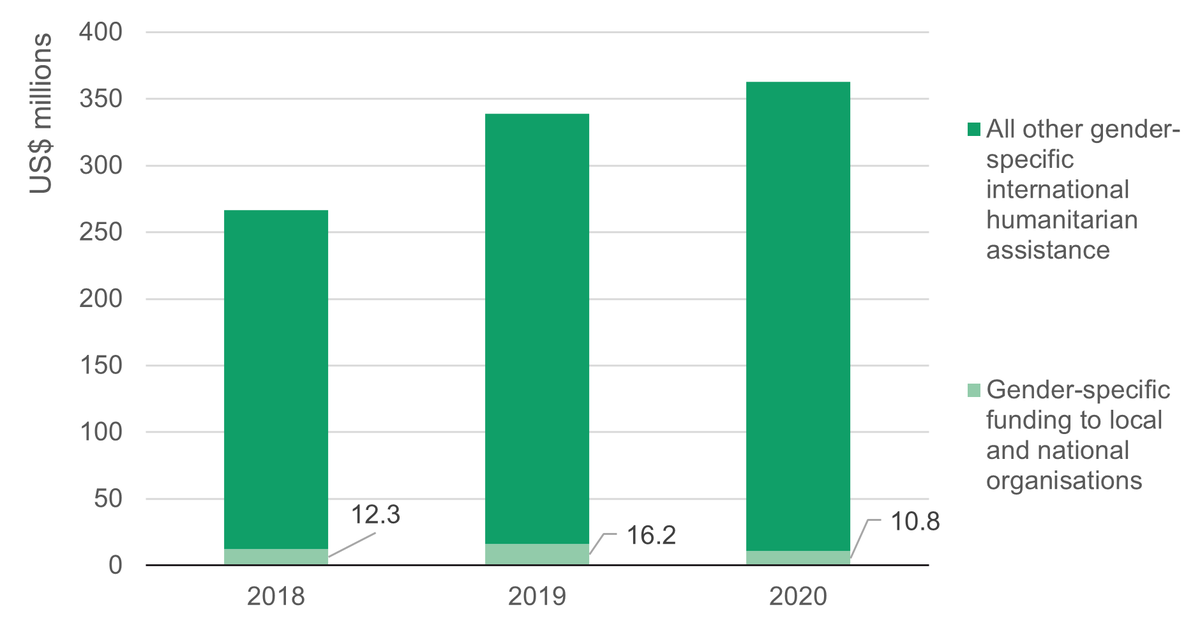

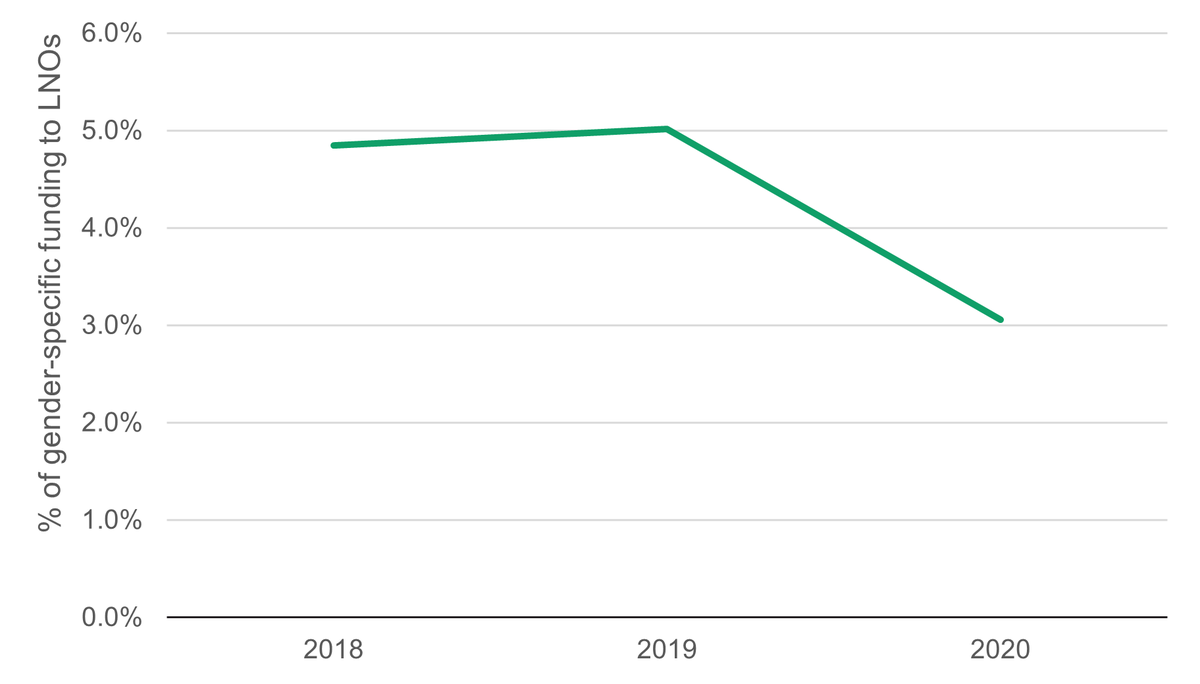

Figure 2.9: Despite an increase in the volume of direct funds reaching local and national organisations, proportion of total assistance provided has declined during the pandemic

Gender-specific international humanitarian assistance to local and national organisations and all other gender-specific funding, 2018–2020

A stacked column chart showing the total volume of gender-specific funding from 2018 to 2020 broken down to what local and national actors receive of the total in US$ millions.

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender-specific funding to

local and national organisations |

12.3 | 16.2 | 10.8 | 7.8 |

|

All other gender-specific

international humanitarian assistance |

254.1 | 322.8 | 352.0 | 547.0 |

|

Proportion of gender specific

funding to LNOs |

4.8% | 5.0% | 3.1% | 1.4% |

Proportion of gender-specific funding to local and national organisations, 2018–2020

A line chart showing the percentage of gender-specific funding to local and national actors from 2018 to 2020.

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender-specific funding to

local and national organisations |

12.3 | 16.2 | 10.8 | 7.8 |

|

All other gender-specific

international humanitarian assistance |

254.1 | 322.8 | 352.0 | 547.0 |

|

Proportion of gender specific

funding to LNOs |

4.8% | 5.0% | 3.1% | 1.4% |

Source: Development Initiatives based on the UN OCHA Financial Tracking Service (FTS).

Notes: Data is in constant 2019 prices and US$ millions. Data was downloaded in January 2022. Note that ‘local and national organisations’ are determined by Development Initiatives’ own internal coding; we are working on further coding to include 2021 data and these figures are subject to update. Analysis elsewhere excludes flows internal to a country/appeal but as most flows to local and national organisations are indirect we include internal flows in this analysis. GBV: gender-based violence. All other gender specific IHA includes GBV and other gender specific funding that was not directly passed on to local and national organisations.

Analysis of global trends in total international humanitarian assistance provided to local and national actors [18] for 2020 shows that funding patterns did not markedly alter from previous years. [19] Hopes that the pandemic might catalyse the long-awaited shift to a more locally led response, with significantly more funding reaching frontline responders directly, were not realised .

Analysis of gender-specific funding received by local and national actors indicates that, as with total international humanitarian assistance, only small volumes were provided in 2020. In fact, 2020 appears to have seen a slight fall in the proportion of gender-specific assistance allocated to local and national actors. While local and national actors often receive funding indirectly through one or more intermediaries, funding beyond the first-level recipient is currently not well reported on the FTS. Thus, while the analysis here captures direct and indirect funding to local and national actors, it is likely that the vast majority of indirect funding is not captured here due to a lack of reporting.

- In 2020, local and national actors received only 3.1% of total reported gender-specific assistance.

- The proportion of total gender-specific assistance provided to local and national actors has reduced from 4.8% in 2018 .

- This is similar to 3.1% of total international humanitarian assistance that was passed to local and national actors directly in 2020. [20]

In the absence of international agency personnel in crisis settings and with rising need, the demand for support from local frontline responders increased. As an advisor to a Palestinian GBV NGO recalled, “During the COVID emergency, we…boosted the capacity of…a national helpline for women and children that is offering remote psychosocial support and because of the pandemic we wanted to have the support available 24/7. We had to step up to have more shifts and more counsellors. All of this costs money”. However, the small volume of funding reaching local and national actors directly and the absence of any significant increase in funding evident in this report’s analysis was consistently recounted in interviews with international and local responders and in other research. [21] A survey of women-led NGOs during the pandemic found that only 3 out of 18 organisations said they were able to access new and additional funding for Covid-19 through UN systems, with some reporting a decline in funds from UN agencies compared with pre-Covid-19 levels. [22] As IRC reported, “despite swift and coordinated international advocacy efforts, funding was neither sufficient nor proportionate to the resources dedicated to the overall pandemic response”. [23] A consequence of the shortfall in funding was increased competition for funding and resources. According to an advisor to the fundraising unit to a GBV NGO in Palestine, this affected the quality of the response: “when you have increased needs of beneficiaries and limited or [the] same amount of funding, it creates a backlash effect among women’s rights organisations because they have to compete for funds. This means less coordination, less cooperation and weaker organisations that have to work on their own”.

Access to information and participation in decision-making

Local actors highlighted various barriers in accessing additional funding for the Covid-19 response. Exclusion from decision-making processes around humanitarian responses and the allocation of funding was reported by a number of organisations consulted, along with challenges in accessing information on available funding. As a representative from a local NGO in Liberia recounted: “Prior to COVID, it was challenging to access not just funding but [also] information on how donors locally invest in the issues around GBV and gender. When COVID came, it became even more real…[for] the donor community and local INGOs, [however, it] took them so long to respond to the gender-specific needs that came up during COVID”. Administrative hurdles, particularly for smaller organisations, were also highlighted: “from my experience, I could say that it is already a challenge to get funds for women-led organisations…the 14 organisations I work with are suffering and not getting the funds because they don’t have the papers or documents to get the funds”, explained an interviewee from Bangladesh.

Quality of funding

The quality of the funding received by local actors as part of the Covid-19 response appeared to vary, both in the flexibility of the funding provided and the coverage of basic programmatic and organisational costs. Some respondents reported that donors showed flexibility, allowing them to adapt their existing funding during the pandemic. However, this was not the experience of all members with others reporting that donors applied stricter requirements to their funding and in so doing impeded the organisations’ ability to respond effectively. Other organisations stated that small-scale grants were being managed with the same onerous bureaucratic procedures of larger grants. Inadequate coverage of overhead costs as well as long delays after the submission of proposals were also raised as barriers to local response. [24] An NGO gender advisor interviewed stated: “it is increasingly expensive to deliver humanitarian aid and often…the quality of the funding that our partners receive does not cover the basic, direct costs, let alone indirect costs that are increasing as a result of increased complexity [in the humanitarian context]”. The Covid-19 response was a ‘missed opportunity’ to make aid more localised and effective during 2020 and 2021. [25]

Notes

-

1

Countries experiencing protracted crises are defined here as those countries with five or more consecutive years of UN-coordinated appeals, as of the year of analysis.Return to source text

-

2

EU institutions includes funding from the European Commission's Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection Department, European Commission’s Directorate-General for International Partnerships (formerly EuropeAid DEVCO) and European Commission’s EU Facility for Refugees in Turkey.Return to source text

-

3

The total volume figures used for this calculation are only based on FTS data because data from the OECD DAC for 2021 is still outstanding. The year-on-year totals used are: US$25.1 billion in 2018, US$25.5 billion in 2019, US$28.7 billion in 2020 and US$26.1 billion in 2021. Figures are preliminary and will be updated for the upcoming Global Humanitarian Assistance report released in June.Return to source text

-

4

As opposed to a broader view of gender in humanitarian action, focused on empowerment of women and girls and inclusion of their voices in the decision making processes.Return to source text

-

5

UN Women and UNFPA, 2020. Funding for gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls in humanitarian programming. Available at: https://www.unfpa.org/publications/funding-gender-equality-and-empowerment-women-and-girls-humanitarian-programmingReturn to source text