Funding for gender-relevant humanitarian response: Chapter 3

Reporting of gender-relevant international humanitarian assistance

DownloadsThe analysis of resourcing trends in this report has aimed to fill a gap in the current understanding of wider gender-relevant funding for humanitarian responses. While this report and others [1] provide some sense of the landscape for gender-relevant funding, the data available restricts our ability to understand fully how, in what form, to and from whom, and at what scale funding is being allocated.

How is gender-relevant humanitarian assistance tracked?

The increased impact of crises on women and girls’ needs is well documented. However, within available data systems and reporting practices, assessing the extent of humanitarian programming and resources that address these needs is challenging. Table 3.1 summarises existing gender markers for development and humanitarian programmes and their functionalities, looking at the DAC Gender Equality Policy Marker, the IASC Gender with Age Marker (GAM) and markers used by individual donors. The existing gender markers share the overarching challenges of their respective data platforms, briefly considered in Table 3.1 and Appendix 1: Methodology .

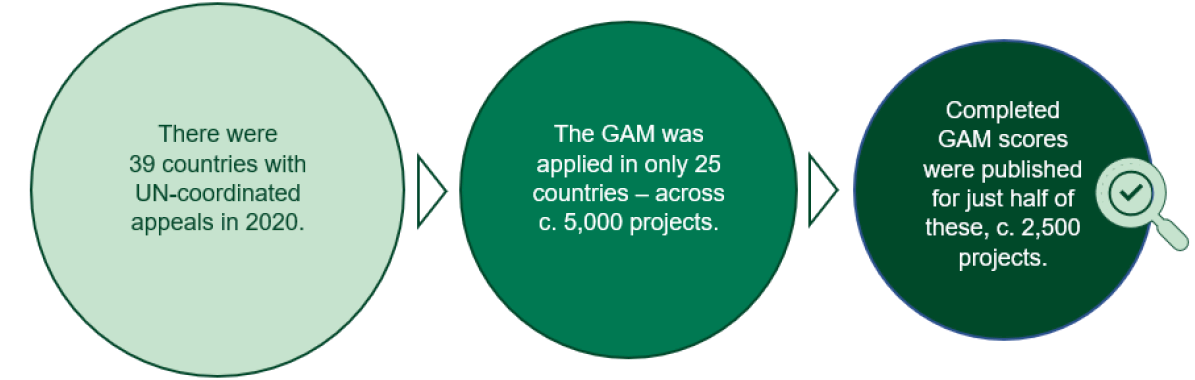

With these markers and indicators, such as the IASC GAM available on the FTS, it is currently not possible to quantify the extent of gender-relevant humanitarian financing across all humanitarian flows and at a global level. The GAM, for instance, is currently only applied to projects within a subset of UN humanitarian response plans on the FTS and only for those plans that are project based. When applied, it tends to flag all projects as gender relevant, without differentiating between the focus of funding (e.g. gender specific versus gender mainstreamed). Analysis undertaken by UN Women and UNFPA has found that classifications significantly overstated the amount of gender-targeted funding in the country contexts analysed. [2]

GAM scores are only available for a small subset of humanitarian funding data

Gender with Age Marker (GAM) availability on the FTS, 2020

An infographic showing three circles with the following text. First circle: "There were 39 countries with UN-coordinated appeals in 2020."; Second circle: "The GAM was applied in only 25 countries - across c. 5,000 projects"; Third circle: "Completed GAM scored were published for just half of these, c. 2,500 projects."

Source: Development Initiatives based on the UN OCHA Financial Tracking Service (FTS) and 2020 GAM Completion Report. [3]

Table 3.1: Gender markers for development and humanitarian programming

| Marker | About | Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAC Gender Equality Policy Marker |

Qualitative statistical tool to record development activities that target gender equality as a policy objective [i]

Introduced by OECD Used across OECD DAC and IATI datasets Main criteria were updated in 2016 [ii] |

Widely used by the group of 30 DAC members (mandatory reporting)

Documented and cross-cutting Consistency of reporting in each individual DAC member 3-level scale Encourages donors to think about gender equality issues |

Self-reported funding leads to inconsistencies across donors [iii]

Lack of timeliness for project- and recipient country-level data [iv] (around 1-year delay) Evaluations of this marker suggest it has been applied inconsistently [v] The lack of sectoral breakdown for humanitarian aid data on the CRS [vi] |

|

Gender and Age

Marker (GAM) |

A tool to design and implement inclusive programmes that respond to gender, age and disability-related needs

Introduced by IASC Used on the GAM Dashboard and FTS (for subset of appeals/plans data) Last revised 2018; questionnaire further revised 2020 |

Promotes inclusive project design and monitoring

Measuring programme effectiveness Teaching and self-monitoring tool Wide set of questions and assessment criteria that could be repurposed |

Difficult to use for financial tracking purposes in its current form

Inconsistent uptake and use Only applicable to subset of appeals data [vii] |

|

Donor’s own

gender markers |

Internal markers that allow donors to track their investments on gender equality

Individual donor such as Canada, Sweden, UK |

Useful self-monitoring tools |

Not on publicly available datasets

Lack of consistency and comparability with other donors |

Notes: CRS: Creditor Reporting System; DAC: Development Assistance Committee; IASC: Inter-Agency Standing Committee; IATI: International Aid Transparency Initiative.

[i] OECD, DAC gender equality policy marker. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/dac/gender-development/dac-gender-equality-marker.htm.

[ii] OECD. Aid in Support of Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/dac/gender-development/aidinsupportofgenderequalityandwomensempowerment.htm.

[iii] Oxfam, 2020. Are They Really Gender Equality Projects? An examination of donors’ gender-mainstreamed and gender-equality focused projects to assess the quality of gender-marked projects. Available at: https://policy-practice.oxfam.org/resources/are-they-really-gender-equality-projects-an-examination-of-donors-gender-mainst-620945/.

[iv] This data includes the information on the Gender Equality Policy Marker and is usually released for the most recent calendar year at least 12 months after the year ends.

[v] Audited projects that were marked with a principal focus on gender equality according to the Gender Equality Policy Marker failed to include the components necessary to effectively address gender inequality issues. Oxfam, 2020. Are They Really Gender Equality Projects? An examination of donors’ gender-mainstreamed and gender-equality focused projects to assess the quality of gender-marked projects. Available at: https://policy-practice.oxfam.org/resources/are-they-really-gender-equality-projects-an-examination-of-donors-gender-mainst-620945/.

[vi] The CRS considers humanitarian assistance as a ‘sector’ within development assistance. The breakdown of the humanitarian assistance sectoral codes on the CRS is different from the global clusters. This means it is not possible to map funding information from the CRS to specific clusters (or even AoRs, such as GBV) in the existing international humanitarian response.

[vii] Flows under response plans that do not use a project-based methodology to aggregate requirements and track funding to the plan (called unit-based appeals) are not usually matched with a GAM score. The GAM as it is currently applied is used on projects, and therefore the GAM scores are linked to project-based appeals on FTS.

Beyond the individual markers used for reporting, the interoperability of global reporting platforms is also a key issue to overcome with gender financing. It is currently not possible to comprehensively link entries from the OECD DAC Creditor Reporting System (CRS) with those on UN OCHA’s FTS. There is no common identifier shared across both platforms that would facilitate this at scale. Even though donor project codes are reported to both platforms, it is voluntary to do so on the FTS and large data gaps exist. The FTS places greater emphasis on the implementers’ project codes (e.g. to be able to map funding to projects within response plans), however these are not reported to the CRS. In addition, other differences in the data architecture (e.g. lack of response plan data on the CRS, different sets of sector breakdowns, less detail on the CRS on recipient organisation names) make it difficult to triangulate data across the FTS and the CRS in the absence of a common identifier. As a result, it is equally difficult to reconcile projects marked under the GAM on the FTS with those marked under the GEPM on the CRS for the same humanitarian contexts and response. This prevents combining all available information on gender relevance for individual projects across global reporting platforms, leaving us with a siloed representation of the reality of gender financing .

Development Initiatives’ approach and learning

Given the challenges with gender markers outlined above, the methodology developed for this report seeks to enable analysis that provides a global estimate of gender-relevant financing. This methodology differentiates between funding for gender-specific and gender-mainstreamed activities. It also allows tracking and analysis of gender financing over time and on a global scale using an automated data collation process, for which very limited analysis of individual project documents is required to sense check findings.

While this methodology allows determination of whether a flow is gender specific or mainstreamed, it does not allow us to ascertain what proportion of the funding in that flow went towards gender-related issues or programming. This is particularly the case for gender-mainstreamed flows, where it is likely only a small and varying proportion of funding is addressing gender-related needs. Thus, most of our analyses and findings do not include gender-mainstreamed flows in aggregates of gender-relevant funding.

For gender-specific flows we believe, based on an assessment of flow descriptions, that at least a significant proportion of the funding would have been directed to gender programming. Thus, our methodology allocates the whole flow as gender relevant. However, we recognise this could lead to overestimation in some cases, and these flows would also benefit from a reported breakdown of the proportion targeting gender-related activities.

Our reliance on flow descriptions to identify gender-relevant financing also means that our identification process would not include flows that lack a detailed enough description or any description altogether. Given that it is voluntary to report flow descriptions to the FTS, there may be some other gender-relevant funding flows that we have not been able to identify and quantify.

The reporting of more granular information on both mainstreamed and specific gender-relevant funding would be a significant step forward. Yet not all gender-specific or gender-mainstreamed approaches are equal. So, what further information on gender-relevant programmes, which would enable identification of good practice in programme delivery, could or should be reported?

Towards better tracking

To ensure that the needs of women and girls in emergencies are met and a gender responsive (and whenever possible transformative) approach is systematically applied, it is essential to have a good-enough picture of levels of funding for these needs. This should include both gender-specific funding (such as that in response to GBV or to sexual, reproductive, maternal and child health) and gender-mainstreamed funding across all sectors of the humanitarian response. For GBV, assessing the funding gap and the extent of underfunding relative to other clusters is also necessary.

In determining what changes to current data platforms, standards, tools and reporting practices should be adopted, there are overarching considerations that should inform how and what choices are made. These include:

- What are the purposes for which data is being reported and the value that having certain data will bring? Purposes could include: to monitor progress against commitments; to provide transparency on funding behaviour; to enable accountability for different stakeholders; to inform programme design, delivery and coordination; and to provide examples of transformative programming, among others.

- Which actors have a stake in the reporting and use of the data to be provided?

- What are the cost and time implications for all those involved in collating, reporting and analysing the data, and how will such costs be borne collectively and equitably?

- What data should be reported at the global level in a standardised format, and what data is more appropriate to be captured at the country, location or project level?

These questions need to be answered collectively by local, national and international stakeholders participating in humanitarian responses. Their user needs and capacity to produce and use this data are at the core of these considerations. With these broader considerations in mind, suggestions for improving the data and reporting on gender-relevant funding at the global level, based on existing reporting practices and tools, are outlined below.

A gender marker for all humanitarian financing flows

Ideally, this would be a gender marker that is harmonised across all aid reporting platforms, including the CRS and the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI). The current system of different markers that do not speak to one another makes reporting gender financing confusing and time-consuming. This disincentivises the reporting needed for monitoring and evaluating responses, with data either not reported or of poor quality. Further, the current marker on the FTS is only used on a subset of flows under appeals that are project based, which leads to significant gaps in the picture of gender-relevant financing at a global level. For funding that falls outside of the UN coordinated appeals, these flows are increasingly reported on the FTS, however large gaps remain. Ideally, a gender marker would be applied on all flows including those outside appeals, as the FTS platform does allow for this reporting.

As UN Women and UNFPA’s [4] consultation found, there is little appetite for a new tracking mechanism, instead existing tracking mechanisms need to be updated to be fit for purpose. How can the GAM be updated and repurposed to act as a gender marker on humanitarian financing flows? This could be done by introducing an associated marker or set of assessment questions in the GAM that would ask whether the programme screened against the GAM supported gender equality and the needs of women and girls as a significant or principal focus (therefore mirroring the assessment in the DAC GEPM). While a ‘gender score’ relying on self-assessment would come with its own limitations, for e.g. challenges with consistency and reliability of results, it has the potential to add value to the tracking of gender-relevant flows at a global level.

Further, there needs to be support and increased attempts to quantify global funding for gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls in humanitarian action and at a global level. While there is a growing attention and analysis on GBV funding, other areas of the gender response in emergencies are not yet tracked or aggregated at a global level, and the transparency of funding trends for prevention and mitigation work is low.

Strengthening reporting against markers

To improve reporting against existing markers, and specifically so that it is easier to identify which flows are gender specific (removing the need for a more time-consuming and potentially less accurate keyword search analysis) it would be useful to have an indicator, highlighting which flows have a primary focus on gender. This could be done adapting the GAM to mirror the assessment of the DAC Gender Equality Policy Marker as proposed above. For GBV funding, a question remains around how much is directed towards GBV prevention and risk mitigation and how much is for GBV response in emergencies. The current data tracking architecture and reporting of funding under the GBV AoR under the Global Protection Cluster does not allow for this differentiation to be reported consistently and comprehensively.

Disaggregating gender data and identifying needs

There are also significant limitations and data gaps in current reporting when it comes to the disaggregation of data, which would need to be addressed to improve tracking of gender-relevant funding. Adapting existing markers, as outlined above, would help to differentiate between mainstreamed funding and funding more specifically targeting gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls. Beyond this, improvements could also be made to ensure that sex, age and disability disaggregated data is consistently collated and analysed to inform humanitarian response plans and refugee response plans. Having this sex, age and disability disaggregated data will help improve the quality and relevance of interventions and ensure that the most vulnerable are targeted. In addition, rapid gender assessments should become a regular and normalised part of the humanitarian programming cycle, conducted at the onset of crises and as part of the annual planning process. Good, disaggregated data and effective gender analysis underpin the effective identification and targeting of need, and as such are fundamental to informing funding decisions.

Funding for GBV programming

Reporting on programmes addressing GBV could be improved by:

- Ensuring GBV programming is consistently incorporated into humanitarian plans, including GBV risk assessments (regardless of costing method or type of plan, e.g. flash appeals)

- Reporting by cluster leads on how sectors are prioritising integrating GBV risk mitigation activities into their response. Here, there are few accountability mechanisms to ensure prevention work is implemented effectively. [5]

Funding for women-led local and national organisations

As this report highlights and has been well documented elsewhere, current reporting practices and platforms do not provide adequate data on funding that passes beyond the first recipient. This funding accounts for the majority that eventually reaches local and national actors, whether for gender-relevant programming or other areas of humanitarian response. A collective commitment by donors and implementing agencies to provide 25% of funding to local and national actors as directly as possible has been made in the Grand Bargain, but it has not yet been realised. Data on funding reaching local and national actors through intermediaries, both the volume of funding but also information on its duration and flexibility, is critical for holding actors accountable to their commitments and for assessing effectiveness and efficiency, and consequently future funding decisions. The onus rests on UN agencies and INGOs to publish this data to existing public data platforms and standards, such as UN OCHA’s FTS and IATI. If necessary, UN agencies and INGOs should alter their internal financial management systems so that they are able to report on the funding they pass to local and national actors. Discussions within the newly formed, and forming, caucuses within the Grand Bargain 2.0 provide an appropriate forum to clearly determine how such progress in reporting can occur. In addition, agreeing a common definition of women’s rights organisations and women-led organisations, an issue being taken forward by the IASC Gender Reference Group, and using this in reporting would provide a much-needed additional level of information to monitor allocations and inform funding decisions.

Notes

-

1

CARE, 2021. Time for a Better Bargain: How the aid system shortchanges women and girls in crisis. Available at: https://www.care-international.org/files/files/FINAL_She_Leads_in_Crisis_Report_3_2_21.pdfReturn to source text

-

2

UN Women and UNFPA, 2020. Funding for gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls in humanitarian programming. Available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/06/funding-for-gender-equality-and-the-empowerment-of-women-and-girls-in-humanitarian-programmingReturn to source text

-

3

2020 GAM Completion Report. Available at: https://www.iascgenderwithagemarker.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Dec-2020-GAM-Results.pdfReturn to source text

-

4

UN Women and UNFPA, 2020. Funding for gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls in humanitarian programming. Available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/06/funding-for-gender-equality-and-the-empowerment-of-women-and-girls-in-humanitarian-programmingReturn to source text

-

5

ELRHA, 2020. Gap Analysis of Gender-Based Violence in Humanitarian Settings: a Global Consultation. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/gap-analysis-gender-based-violence-humanitarian-settings-global-consultationReturn to source text