Funding to local actors: evidence from the Syrian refugee response in Türkiye: Chapter 2

Background

DownloadsThis chapter sets out the background to Türkiye’s policy and programmatic response to the mass migration of Syrian refugees, as well as the international response and role of civil society in Türkiye. It then provides an overview of trends in total international grant funding to Türkiye to give wider context to the following analysis of international funding specifically for the refugee response.

Displacement context

The crisis in Syria has caused one of the largest displacements of people in the world to date, with over 5.5 million people seeking asylum in neighbouring countries. There are currently 3.7 million registered Syrians under temporary protection in Türkiye, as well as 330,000 refugees and asylum seekers of other nationalities under international protection. [1] Türkiye initially adopted an open-door policy to Syrians fleeing the conflict with large numbers of refugees arriving every year from 2012 until 2016, when the government brought in more restrictive measures to gain control over rising numbers. [2] Since 2018 the annual increase in registered Syrian refugees in the country is mainly from newborn babies. There are likely significant numbers of additional refugees in Türkiye who are not registered with the authorities. A decade after the conflict began, there are few durable solutions available to Syrian refugees in Türkiye. Only 7,400 refugees were resettled to a third country in 2021, and the number of voluntary returns remains very low. [3]

The protracted nature and scale of displacement has put significant pressure on the provision of public services, housing and infrastructure and the labour market in Türkiye. The vast majority of refugees live in urban areas, and continue to face numerous challenges, including linguistic barriers, access to formal livelihood opportunities and high incidences of poverty in a context defined by high living costs and low wages. [4] The impacts of Covid-19 and the recent economic crisis in Türkiye have disproportionately affected refugees, especially women, who mainly work in the informal labour market. With the rising cost of living and depleted assets, many have been pushed deeper into poverty. In recent years, these factors, as well as the common politicisation of refugee hosting and negative public perceptions of refugee policy, have all affected social tensions between Syrian refugees and host communities. [5]

Legal and policy framework

While Türkiye is a signatory to the 1951 Geneva Convention, it maintains a geographical reservation meaning that the Convention is only applied to refugees from Europe. Nevertheless, a legal framework, building on an asylum system that was first developed in 1990, [6] has been adapted by the government, including the Law on Foreigners and International Protection (2013) and the Temporary Protection Regulation (2014). Together, these regulations have formalised the situation for Syrians by granting access to employment, social assistance, education and health services, as well as respect of nonrefoulement. [7]

Registered Syrian refugees in Türkiye are entitled to healthcare, education and social assistance in the province in which they are registered, provided mainly free of charge by the government. Refugee policy in Türkiye has increasingly sought to integrate refugee services into existing national systems. As such, healthcare is provided to Syrians through public hospitals and migrant health centres, and Syrian children are subject to the compulsory education policy of the country and registered at public schools. The Government of Türkiye (GoT) has been increasingly supportive of the transition of refugees from humanitarian assistance to more development-focused interventions. [8]

Response coordination

The GoT leads the response to the Syrian refugee crisis with international support. In 2014 the Directorate General of Migration Management was established and tasked with coordinating the refugee response including the registration of Syrians, taking over from the Disaster and Emergency Management Authority. Many different line ministries are also involved in the response, including the Ministry of Health, Ministry of National Education, Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Security, as well as municipalities who play a critical, though more informal, role in providing services for refugees. [9]

The GoT did not initially request international support for the refugee response, believing the crisis would not last long. In the early years, international activity in Türkiye was mainly limited to cross-border activities into Syria. However, as more refugees sought to claim asylum in European countries, European donor funding to Türkiye substantially increased. This culminated in the ‘EU-Turkey Deal’ in 2016 which sought measures to address unauthorised migration into Europe in exchange for support to Türkiye to manage the costs of hosting refugees. [10] As a result of increased funding in 2015, several UN agencies and INGOs started to play a much larger role in supporting the government-led refugee response in the country. Support from international partners has been consolidated through the annual, UN-led Türkiye chapter of the Syria Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan (3RP), which combines both humanitarian and development refugee responses into a single plan. The 3RP acts as both a coordination, fundraising and strategic planning platform and is led by the UN Development Programme (UNDP) and the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), in cooperation with the government.

International organisations have mainly supported the government’s response to the refugee crisis by funding public institutions, helping to strengthen capacity to meet the increased needs and filling gaps left by government institutions. International support is provided in various sectors including livelihoods, education, language training, protection, psychosocial support and social cohesion activities. Assistance mobilised under the 3RP has been largely directed towards supporting public services and systems under pressure due to the influx of refugees, as well as promoting the self-reliance of refugees. By far the leading source of international financial assistance has come from the EU. A key outcome of the EU-Turkey deal was the Facility for Refugees (FRIT), which was established to coordinate EU resources to address the urgent needs of refugees and host communities in Türkiye (see Box 2 ).

Civil society in Türkiye has also played a critical role in the Syrian refugee response. Türkiye-based NGOs can have different legal structures, including foundations, associations and cooperatives. Since 2012, there has been a marked increase in the number of different NGOs registered in Türkiye, including refugee-led organisations. [11] L/NNGOs quickly started to play an important role in the Syrian refugee response, providing emergency services and support to vulnerable communities, especially those in hard-to-reach areas. In addition to already well-established national organisations with national and international experience, such as the Association for Solidarity with Refugees and Migrants (SGDD/ASAM), Support to Life (STL), the Human Resources Development Foundation (IKGV), the Foundation for the Support of Women’s Work, the Humanitarian Relief Foundation (IHH), Mavi Kalem and International Blue Crescent (IBC), many new organisations directly targeting refugee communities were founded after 2011. These included refugee-led organisations such as SENED, Watan Foundation and the Syrian Solidarity Foundation. [12] The experience and knowledge of L/NNGOs has increased as a result. The arrival of international organisations and new funding opportunities has at times helped to expand learning opportunities for civil society organisations in Türkiye. Well-established organisations, such as SGDD/ASAM, IHH, Mavi Kalem, IKGV, IBC and STL, have become highly active, delivering services to refugees and raising awareness of needs, partly through international funding. The TRC is one of the most important national actors, delivering two of the largest EU-funded cash transfer programmes for Syrian refugees (see Box 2). Local networks, including the Localisation Advocacy Group and TMK, have become increasingly active, advocating for the localisation of aid in Türkiye and improved policies to support the refugee response.

Global policy context

International support to the refugee response in Türkiye over the past decade is set against the backdrop of wider aid reform around ‘localisation’ – a broad movement advocating for locally led practices, made up of numerous initiatives, commitments, models and pledges. [13] Different dimensions of localisation, including direct and quality funding, equitable partnerships, greater participation of affected communities and increased presence in coordination mechanisms, all seek to ensure that crisis preparedness and response capacity lies with those most affected. [14] More recently, the discussion around ‘localisation’ has moved on to discussion around the decolonisation of aid.

Increasing both the quantity and quality of funding to LNAs has been recognised as critical to practically realising more locally driven action. [15] The current funding arrangement which channels most funding to LNAs through one or more international intermediary organisations, limits the participation of local actors in strategic planning, coordination and decision-making and has implications for the effectiveness of the response and the sustainability of LNAs. [16] This includes women’s rights and women-led organisations [17] and refugee-led organisations, [18] who often represent the most vulnerable communities. Though the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic further reinforced the centrality of LNAs in humanitarian response, the increased rhetoric around the importance of locally led leadership has not necessarily translated into action, [19] including for women’s rights and women-led organisations .

The Grand Bargain in 2016 saw signatories pledge to pass 25% of international humanitarian assistance ‘as directly as possible’ to LNAs as well as increase the quality of that funding, including multi-year and flexible funding. Localisation and quality funding were named as the overarching priorities of the Grand Bargain 2.0 and a caucus launched in June 2022 is focused on reaching political agreement on how to increase funding to LNAs, including funding for overheads. [20] INGO signatories of initiatives such as the Charter for Change and Pledge for Change have made commitments to increase direct funding, including core funding, and improve partnerships to address inequalities in the humanitarian sector.

In response to a general decline of international support for refugees and the countries hosting them, the Global Compact on Refugees in 2018 reinforced the need for more predictable and equitable responsibility sharing between refugee-hosting countries and donor countries. It also highlighted the importance of partnership approaches and the role of local actors as responders in displacement contexts. [21] More broadly, there has been a recognition of the need to strengthen synergies and improve coordination between the humanitarian, development and peacebuilding sectors in order to move toward more lasting solutions, especially in situations of protracted crisis and displacement. Within the development aid effectiveness agenda, the concept of country ownership, which emphasises that development agendas should be nationally driven and led, also has a long history (2005 Paris, 2008 Accra, 2011 Busan), with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development putting emphasis on the Sustainable Development Goals being rooted in national priorities and implemented through national systems. [22]

Financing context

Türkiye has contributed huge amounts of domestic resources to the refugee response. While exact figures are not easy to calculate, estimated spending based on data from Turkish authorities suggests that Türkiye spent over US$30 billion in the period 2012 to 2017. [23] In 2020, Türkiye voluntarily reported to the OECD DAC CRS US$7.3 billion of international humanitarian assistance, which is largely expenditure on hosting Syrian refugees inside Türkiye.

In addition, as both a recipient and donor of official development assistance (ODA), Türkiye has received significant volumes of international funding to support the refugee response along with other hosting countries such as Jordan and Lebanon. [24] In 2020, Türkiye was one of the ten largest recipients of international humanitarian assistance. [25] The following section provides an overview of overall ODA trends to Türkiye followed by findings on funding specifically provided for the Syrian refugee response.

Trends in overall international funding to Türkiye

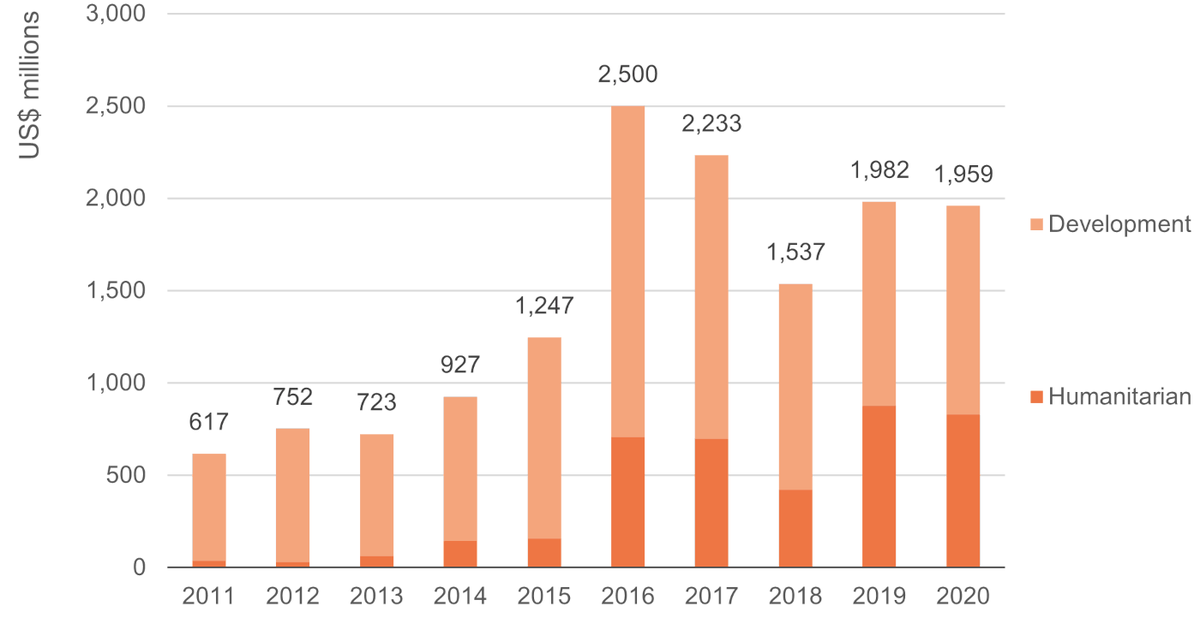

International grant funding to Türkiye significantly increased as the Syrian crisis evolved. Figure 1 shows total ODA grant funding to Türkiye reported to the OECD DAC CRS from 2011 to 2020 (US$14.5 billion). It is important to note that this includes all international grant funding, and not funding solely directed to the Syrian refugee response.

Figure 1: Total official development assistance grants to Türkiye, 2011–2020

Bar chart showing total official development assistance grants to Türkiye, 2011–2020

Source: Development Initiatives based on Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Creditor Reporting System (CRS).

Notes: Funding figures include disbursements from OECD DAC members, from multilateral organisations and from other government donors that voluntarily report their international assistance to the OECD DAC. Data is in constant 2020 prices.

Before 2016, the GoT did not receive significant additional international support to manage the arrival of Syrian refugees. The sharp increase in numbers of people seeking asylum in European countries in 2015, and the subsequent signing of the EU–Turkey Deal in 2016, marked a notable turning point in the involvement of international actors in the refugee response in Türkiye.

- International grant funding to Türkiye more than doubled in 2016 to US$2.5 billion, following the signing of the EU–Turkey Deal. Since then, grant funding has slightly decreased and, after a drop in 2018, has remained at around US$2 billion per year, still significantly higher than pre-2016 levels.

- The launch of the FRIT, a key output of the EU–Turkey Deal, also saw the proportion of total grant ODA provided as humanitarian assistance to Türkiye increase, from 13% (US$159 million) in 2015 to 28% (US$708 million) in 2016. Since 2019, this has increased further, to 44% in 2019 and 42% in 2020. Similar to the response in Jordan and Lebanon, [26] development assistance to Türkiye is high, in part due to FRIT which has mobilised large volumes of both development and humanitarian funding.

- Funding reported to the OECD DAC shows that by far the largest donor of overall grant funding to Türkiye has been the EU, which has provided US$8.2 billion – over half (57%) of the international grant assistance provided between 2011 and 2020. Other large donors of grant funding to Türkiye since 2011 have been Germany (US$2.2 billion), France (US$685 million), the UK (US$624 million) and the US (US$461 million).

- The GoT has been the largest recipient of total grant funding for Türkiye since 2011, receiving 37% (US$5.4 billion) of total funding. The vast majority of which has been development funding.

- UN agencies have received the bulk of the humanitarian grant funding since 2011 (US$1.6 billion), accounting for 40% of the total humanitarian grant funding to Türkiye since 2011.

- Reporting of funding on the OECD DAC’s CRS which passes directly to L/NNGOs is incomplete and it is not possible – on the CRS or other data platforms – to track the volumes of international funding that reaches LNAs as second or third-level recipients. To overcome this, DI collected data directly from donors (see Figure 3).

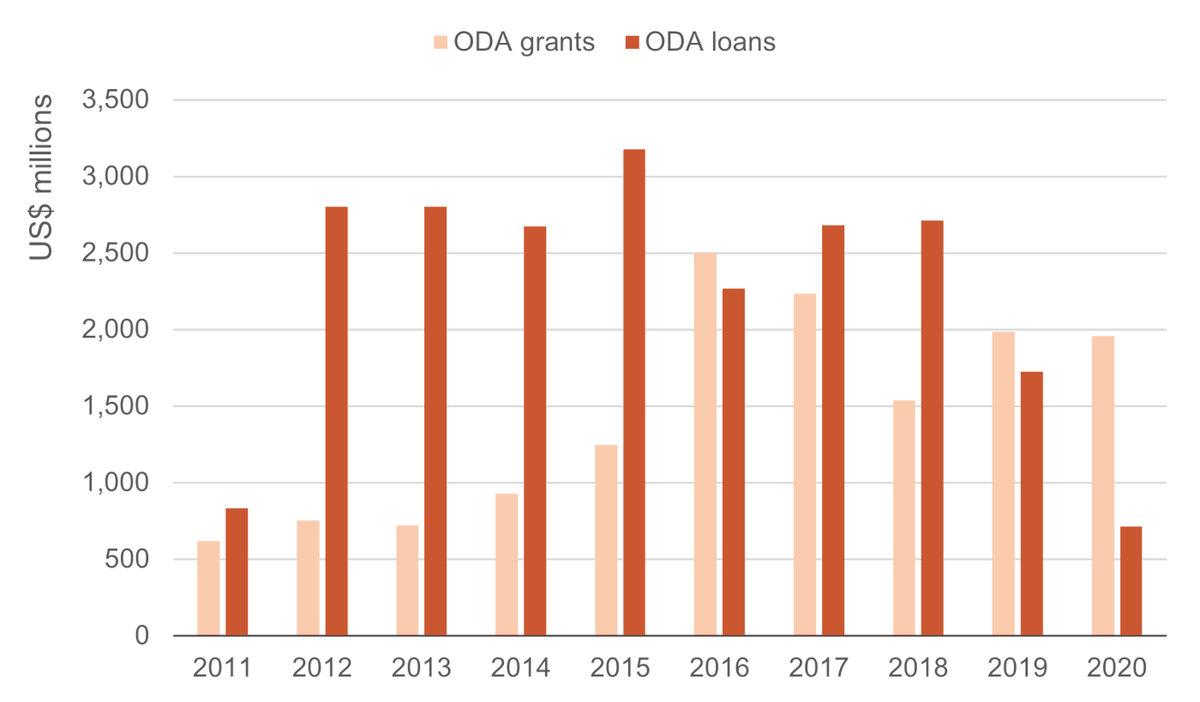

While this study focuses on international grant funding, Türkiye has also been a recipient of ODA loans. Figure 2 shows total ODA disbursed as grants and loans to Türkiye since 2011. It is important to note that this includes all loan and grant ODA funding to Türkiye, and not funding solely directed to the Syrian refugee response.

Figure 2: Total ODA to Türkiye 2011–2020, grants and loans

Bar chart showing total ODA to Türkiye 2011–2020, grants and loans

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD DAC Creditor Reporting System (CRS).

Notes: Data is in constant 2020 prices. Funding figures include disbursements from OECD DAC members, from multilateral organisations and from other government donors that voluntarily report their international assistance to the OECD DAC. Data is in constant 2020 prices.

- Lending to Türkiye increased sharply after conflict in Syria broke out in 2011, peaking in 2015 at US$3.2 billion. Since 2018, ODA provided as loans has notably decreased, and in 2019 grants overtook loans as the largest type of ODA to Türkiye.

- Recent 3RP research into IFI refugee financing found that, for the period 2013 to 2025, IFIs have provided or have committed to providing US$1.5 billion (42% of the total) in ODA loans to municipalities and government institutions in support of the Syrian crisis in Türkiye. [27] Since 2014, most humanitarian funding for Türkiye has been provided as grants (in 2020 reaching 100%). Grants have also grown as a proportion of development funding since 2015, reaching 60% of development ODA in 2020.

International grant funding specific to the refugee response

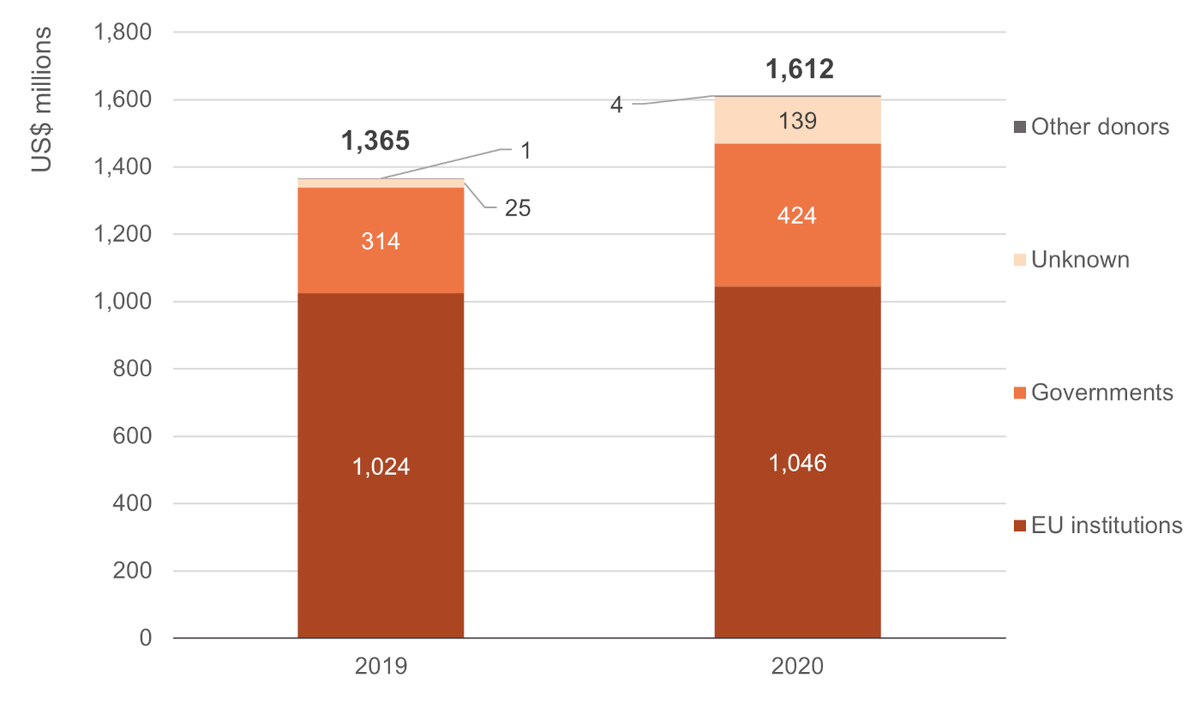

Much of the grant funding received by Türkiye has been provided specifically for the Syrian refugee response. However, in the absence of comprehensive, publicly available data on the total volumes of funding made available for the Syrian refugee response, DI and TMK collected data directly from donors and implementers, on both humanitarian and development funding. Funding data for both 2019 and 2020 was collected, as shown in Figure 3. Our dataset captures the majority of funding flows but inevitably, not all flows were possible to identify and therefore the totals are likely to be slightly underestimated (see ‘ Methodology ’ section).

Figure 3: Total grant funding to Türkiye for the Syrian refugee response by donor type, 2019–2020

Chart showing total grant funding to Türkiye for the Syrian refugee response by donor type, 2019–2020

Source: Development Initiatives based on survey data provided directly by donors and intermediaries, UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA)’s Financial Tracking Service (FTS), OECD DAC Creditor Reporting System (CRS), International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) data and publicly accessible project lists for individual organisations.

Notes: Unknown totals include funding based on intermediaries’ response budgets, where the source donor information was not provided. ‘Other donors’ category includes funding from global funds (the Central Emergency Response Fund and the Covid-19 Humanitarian Thematic Fund) and from private individuals and organisations. Data is in current prices.

- Our data collection captured US$1.6 billion in funding for the Syrian refugee response in 2020 and US$1.4 billion in 2019.

- According to data collected for this study, and in line with the overall CRS trends analysis, the largest donor to the refugee response in Türkiye in 2019 and 2020 was the EU, providing just over US$1 billion each year.

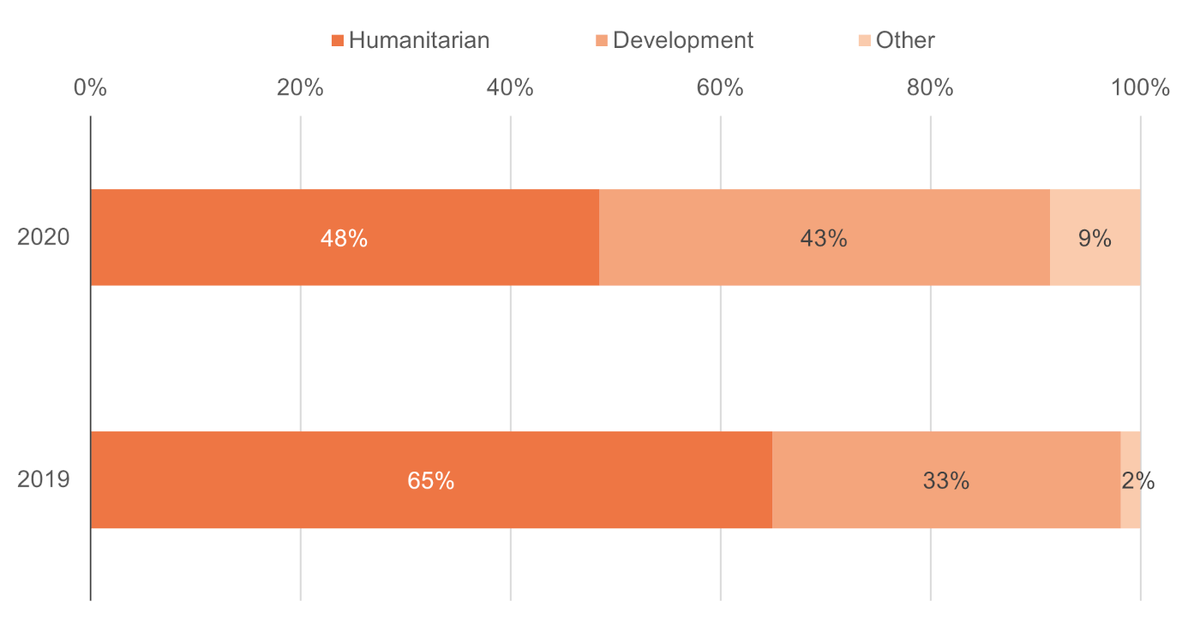

Most donor funding to Türkiye for the Syrian refugee response is provided as humanitarian assistance, though both the proportion and volumes provided as development assistance grew between 2019 and 2020 (see Figure 4 ).

Figure 4: Total humanitarian and development grant funding to Türkiye for the Syrian refugee response, 2019–2020

Chart showing total humanitarian and development grant funding to Türkiye for the Syrian refugee response, 2019–2020

Source: Development Initiatives based on survey data provided directly by donors and intermediaries, UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA)’s Financial Tracking Service (FTS), OECD DAC Creditor Reporting System (CRS), International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) data and publicly accessible project lists for individual organisations.

Notes: The breakdown of humanitarian and development funding is based on self-reports by funding providers. The category ‘other’ refers to instances where donors opted to classify grant funding as neither development nor humanitarian funding for unknown reasons. The breakdown only reflects funding that has been classified by the respective donor. [28] Data is in current prices.

- Based on DI’s donor data, between 2019 and 2020, development assistance grew from US$453 million, 33% of total donor funding, to US$692 million (43%).

- Over the same period, the volume of grant funding provided for the refugee response as humanitarian assistance decreased, from US$887 million in 2019 to US$781 million in 2020, falling from 65% to 48% of total assistance provided. [29]

Box 2

The EU Facility for Refugees in Türkiye (FRIT)

The Facility for Refugees in Türkiye (FRIT) is a EUR 6 billion funding mechanism established by the EU in 2015 to channel both humanitarian and development support to refugees and affected host communities in Türkiye. The launch of the FRIT marked a significant step-up in EU support to Türkiye and was a key outcome of the EU–Turkey Joint Action Plan (2015) and the EU–Turkey Deal (2016) which aimed to limit migration movements from Türkiye to Europe in return for increased cost-sharing of Türkiye’s refugee hosting by EU countries. [30]

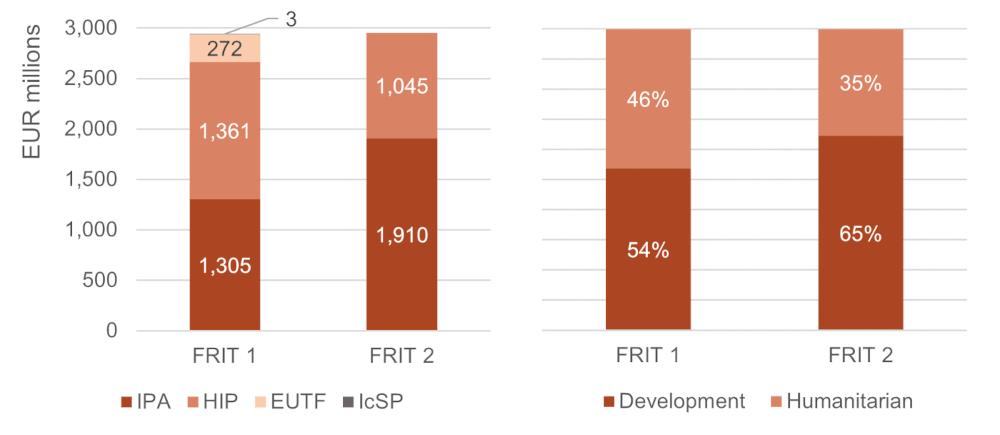

The FRIT is funded both from the EU budget and additional contributions from member states based on their share of the EU’s gross national income (GNI). It is organised in two tranches of EUR 3 billion (see Figure 5), both of which have been fully committed: the first until mid-2021, and the second funding projects that will be fully implemented by 2025. The FRIT has funded both humanitarian and development projects, with the development portion increasing in the second tranche, from 54% (EUR 1.6 billion) to 65% (EUR 1.9 billion) of total funding.

Figure 5: FRIT commitments by external financing instrument and by aid type

Chart showing FRIT commitments by external financing instrument and by aid type

Source: DI based on EU data, updated 31 January 2022.

Notes: Commitments total EUR 3 billion for each tranche including additional support and operational lines. EUTF = EU Regional Trust Fund (Madad); HIP = Humanitarian Implementation Plan; IcSP = Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace; IPA = Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance.

As a coordination mechanism rather than a fund, FRIT funding is channelled through existing EU external financing instruments (EFIs) [31] (see Figure 5) and operates within EFI global regulations. As is the case with EFIs used in other contexts outside Türkiye, none of the FRIT EFIs allow L/NNGOs to be funded directly due to recipient eligibility requirements. The exception to this rule is the EU Regional Trust Fund (Madad) (EUTF).

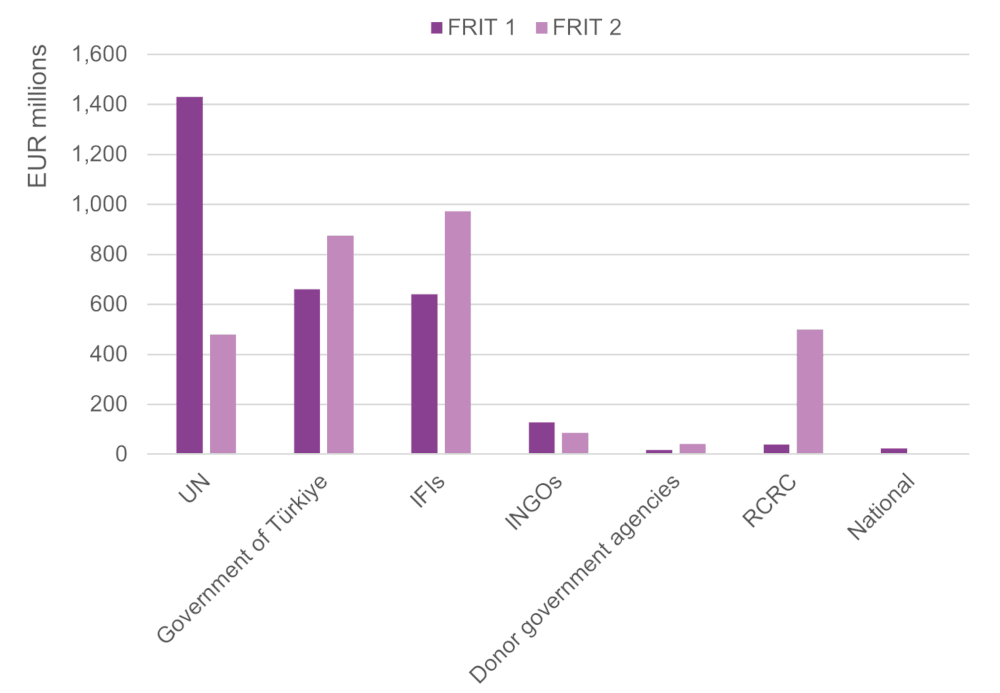

Figure 6: FRIT commitments by recipient, first and second tranche

Bar chart showing FRIT commitments by recipient, first and second tranche

Source: DI based on EU data, updated 31 January 2022.

Notes: Donor government agencies include the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ), Agence Française de Développement (AFD) and Expertise France. Two national actors were funded under the first FRIT tranche: the Association for Solidarity with Asylum Seekers and Migrants, and the Union of Chambers and Commodity Exchanges of Türkiye. FRIT = Facility for Refugees; IFI = international financial institution; INGO = international NGO; RCRC = International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, here includes funding to the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and the Danish Red Cross.

As the balance of different instruments has changed between tranches, so have the funding recipients (see Figure 6). UN agencies were the largest recipients under the first tranche, though funding to the UN fell from 45% (EUR 1,430 million) of FRIT 1 to 16% (EUR 479 million) of FRIT 2, while funding to government institutions, IFIs and other international development organisations increased. In total, funding to the Directorate General of Migration Management and government ministries increased from 22% (EUR 660 million) of total funding to 29% (EUR 875 million) between tranches. The largest increase in funding was to the International RCRC movement organisations, from EUR 38 million to EUR 500 million. Only FRIT 1 involved any funding through the EUTF and therefore any direct funding to national civil society. [32] In the first tranche, 9% of total FRIT funding was channelled through the EUTF. Of this, 9% (EUR 23 million) was passed to national NGOs, or approximately 0.8% of the total amount of funding of the first tranche.

The FRIT has provided assistance in areas such as education, health, municipal infrastructure and socioeconomic assistance. The largest FRIT-funded programme is the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN) cash transfer programme which was launched in 2016. [33] Since 2017, the EU has also supported humanitarian cash transfers under the Conditional Cash Transfers for Education, which is modelled on an existing Turkish programme. [34] Both programmes have been funded by the EU beyond the second FRIT tranche. [35]

Downloads

Notes

-

1

UNHCR. Türkiye: Latest updates, available at: https://reporting.unhcr.org/turkey#toc-latest-updates . Note that Türkiye does not recognise Syrians as ‘refugees’ in the legal sense due to Türkiye’s interpretation of the 1951 Geneva convention which applies a geographic limitation to only recognise refugees from Europe.Return to source text

-

2

Center for American Progress, 2019. Turkey’s Refugee Dilemma, available at: www.americanprogress.org/article/turkeys-refugee-dilemmaReturn to source text

-

3

UNHCR Türkiye, 2021. 2021 Operational Highlights, available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/turkiye/unhcr-turkiye-2021-operational-highlightsReturn to source text

-

4

UNHCR, 2022. Turkey 3RP Country Chapter 2021-2022, available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/turkey/turkey-3rp-country-chapter-2021-22-updated-2022-entrReturn to source text

-

5

Center for American Progress, 2019. See note 14.Return to source text