Gender-based violence and the nexus: global lessons from the Syria crisis response for financing, policy and practice: Chapter 2

Global efforts at the nexus to end GBV

DownloadsIn addition to representing separate funding streams, humanitarian and development actors have different mandates, objectives and ways of working. Humanitarian assistance focuses on life-saving and immediate support to the most vulnerable people impacted by crisis, typically working outside government channels and with short project cycles. Development assistance, on the other hand, is longer term and tends to involve partnerships with national government and non-governmental actors to bring about policy, institutional and systemic change that will improve the social, economic and environmental wellbeing of populations in developing countries.

At the same time, the line between humanitarian and development contexts is increasingly blurred. Donors and multilateral institutions increasingly deploy development assistance in fragile and conflict-affected contexts [1] and have taken steps to adapt their approaches, for example by developing peace, security, resilience and risk-reduction programmes. Humanitarian actors increasingly operate in protracted crises and have made commitments that enable longer term, adaptive programming and greater national ownership, including the move towards multi-year, flexible funding and the localisation of aid.

This section examines how humanitarian and development assistance addresses GBV – looking at issues of policy, financing and coordination from the perspective of each as well as the areas of inter-connection.

GBV-related policies across the nexus

The women, peace and security (WPS) agenda is a comprehensive normative framework for efforts to deal with the multifaceted challenges women face in conflict contexts. Guided by UN Security Council resolution 1325 (2000) on WPS, with its four pillars of prevention, participation, protection, and peacebuilding and recovery, the agenda has been expanded and reinforced with nine resolutions including UN Security Council resolution 1820 (2008) on conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV). [2] All of these resolutions recognise the importance of protecting women from violence, particularly GBV, during and after conflict. At the same time, the WPS agenda emphasises women’s full and equal participation and representation in conflict prevention, resolution and post-conflict recovery and women’s agency in conflict transformation. Thus, it is a wide-ranging agenda that encompasses peace and security, development, and humanitarian actors.

From the perspective of humanitarian policy, protection is a central objective of all humanitarian action [3] and GBV is one of the protection risks that must be addressed in emergencies. Although humanitarians do not physically protect people from harm, they do have an obligation to reduce risk and help people stay safe, as well as to help them restore dignity and recover from violence or abuse. The Inter-Agency Steering Committee (IASC) – the primary mechanism for inter-agency coordination of humanitarian assistance – approved guidelines on integrating GBV in humanitarian action in 2015. [4] This makes clear that it is the collective responsibility of all humanitarian actors to prevent and mitigate GBV risks within their areas of operation.

Humanitarian programming to address GBV typically has three main strands: (1) provision of specialised services to survivors – establishing GBV case management systems that link survivors to a package of services that includes, but is not limited to, health (including the clinical management of rape, mental health and psychosocial support), legal services, and safety and security; (2) risk mitigation – incorporating actions into all humanitarian sectors to mitigate GBV risk (e.g. within the water, sanitation and hygiene sector, building sex-segregated latrines with locks and lighting) and (3) prevention – this may include community-based outreach to change attitudes, beliefs and social norms that are the basis for GBV and actions to promote gender equality across all sectors of the humanitarian response. Humanitarian programming is based on a multi-sector model that includes creating and monitoring referral pathways to ensure continuity in the management of GBV cases as well as the presence and quality of services in each element of the response. [5]

Although humanitarian policy calls for a comprehensive approach, the delivery of GBV services in humanitarian crises remains piecemeal. [6] In the context of limited resources, humanitarian actors prioritise the most pressing needs – often related to providing health and case management services to survivors of rape and sexual violence. Although they recognise that other forms of GBV, such as early marriage and domestic violence, are often worsened due to crisis, and the importance of prevention, they often struggle to raise funds for this. Furthermore, integration of actions to address GBV across other humanitarian sectors is often uneven. The key reason for this, from the perspective of the International Rescue Committee (IRC) and echoed by other humanitarian agencies in the field, is that GBV prevention and response is underfunded and “treated as a ‘second tier’ priority” in crises. [7] This is despite over a decade of advocacy and efforts to build inter-agency cooperation on GBV in crises through initiatives such as the Call to Action on Protection from Gender-Based Violence in Emergencies. [8]

Development policy and programming often treats GBV as a manifestation of gender inequality and the systemic cultural, political, institutional and economic subordination of women. For example, SDG 5 on gender equality and women’s empowerment includes targets to end all forms of violence against women and girls in the public and private spheres (including trafficking, sexual and other forms of exploitation) and to eliminate harmful practices such as child, early and forced marriage, and female genital mutilation. Development initiatives have more scope to address GBV in its wider sense, including forced and early marriage, domestic violence, harmful practices, and other forms of exploitation and abuse. They also typically take a more holistic approach to prevention and response that is linked with wider efforts to empower women. Development programmes focusing on GBV may include interventions to raise awareness and change social norms and behaviour, including by engaging men and traditional or religious leaders; develop and reform policies and laws relating to GBV; provide psychosocial support to survivors and address stigma they face within their communities; support women’s economic empowerment, including income-generation opportunities for survivors; and increase women’s access to reproductive health services and sensitive and appropriate legal and justice services. In conflict-affected contexts, development and peace and security actors also address GBV in the context of security and justice sector programmes, including efforts to improve the conduct of security forces and end impunity for CRSV.

Among development institutions the World Bank is at the forefront of efforts to step up commitments to GBV prevention and response and integrate it across all sectors of support in crisis contexts. It supports over US$300 million in development projects aimed at addressing GBV, both through standalone projects and by integrating GBV components into sector support in areas such as transport, education, social protection and forced displacement. This has included support to a number of GBV-focused projects in crisis settings, including a US$100 million GBV prevention project in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and a US$107 million project focusing on multi-sectoral services to GBV survivors the Great Lakes region. The World Bank has also strengthened efforts to address risks of sexual exploitation and abuse in the projects they support.

Financing to end GBV

Financing is crucial to realising all of these commitments – not only to fund programmes but also to incentivise a nexus approach. Several recent studies make clear that the current funding architecture is failing to mobilise sufficient funding for the humanitarian response to GBV in crisis settings. [9] Twenty-one donors have recently stepped up their financial commitment, pledging US$363 million to GBV in humanitarian crises at the 2019 Oslo Conference. [10] In order to bridge humanitarian and development approaches to GBV, development funding also needs to prioritise GBV in crisis settings, however this is under-explored. The following section examines humanitarian and development financing of GBV, including an analysis of official development assistance (ODA) targeting GBV.

Humanitarian financing

GBV remains an underfunded area of humanitarian response compared with other sectors. [11] According to a recent study by VOICE and the IRC, humanitarian funding allocated to GBV between 2016 and 2018 amounted to US$ 51.7 million – only 0.12% of the US$ 41.5 billion spent on humanitarian assistance. This represents only one-third of the US$155.9 million requested. [12] Furthermore, these funding requests do not match the real scale of the problem and needs – agencies report that they frequently adjust appeals to reflect expectations of what donors will realistically support. [13]

While we know that there are major gaps in GBV funding in crises, the financial tracking of humanitarian assistance to GBV is challenging for several reasons, making it difficult to monitor progress towards commitments. Firstly, although GBV is a separate ‘Area of Responsibility’ or sub-sector within the protection sector, funding for GBV is rarely reported separately – usually only aggregate funding for protection is reported. Furthermore, GBV prevention and risk mitigation actions that are integrated into other sectors, such as health or water, sanitation and hygiene, are hidden within those sectors. In part because GBV is a less established and distinct sector, organisations do not report GBV projects in a consistent and standardised way to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)’s Financial Tracking Service (FTS) – the platform that provides the most detailed data about the funding of humanitarian appeals and response plans – making it challenging to aggregate and compare data. Finally, reporting to the FTS on humanitarian aid flows channelled outside of appeals or to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)-led Refugee Response Plans (RRPs) often does not provide the same level of detail as for OCHA-led Humanitarian Response Plans (HRPs), making it more difficult to track GBV funding outside of humanitarian appeals. [14]

Development financing

GBV is a very small but growing focus of development finance. The OECD Creditor Reporting System (CRS) – the most comprehensive and reliable data source on ODA – introduced a new code for aid to end violence against women and girls in order to improve accountability and tracking. The ‘violence against women and girls’ purpose code may however under-represent GBV funding, especially in crisis situations, as donors can report under one purpose code based on the primary purpose of the aid. For example, aid cannot be reported under both the ‘violence against women and girls’ purpose code and one of the humanitarian purpose codes. [15] ODA from the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donors reported under the ‘ending violence against women and girls’ purpose code more than tripled from US$122 million in 2016 to US$389 million in 2018. This spike is largely due to an eight-fold increase in EU funding for GBV connected with the Spotlight Initiative (see Appendix 3 for more details). Canada, the UK and Spain also more than doubled their contributions from 2016 to 2018. Despite this, the US$389 million targeting GBV in 2018 still represents only 0.26% per cent of the US$147 billion in total ODA from DAC donors that year. [16]

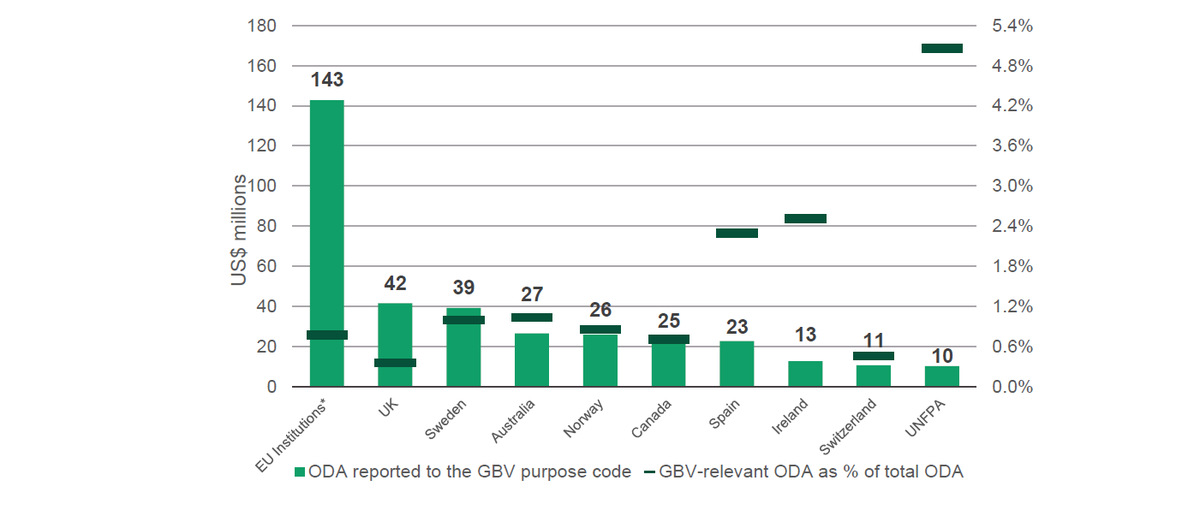

Figure 1: Top ten donors of GBV-relevant ODA in 2018

Top ten donors of GBV-relevant ODA in 2018

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Creditor Reporting System (CRS).

Notes: Data is in constant 2017 prices. Figures only include projects reported to the CRS by donors and coded with the purpose code 15180 – ending violence against women and girls. Total ODA refers to total gross bilateral ODA as recorded in the CRS. *The EU is a member of the OECD DAC. UNFPA: United Nations Populations Fund.

There is a substantial disparity between donors. Figure 1 shows the top ten donors of ODA targeting GBV in 2018. Three of these – the EU, Sweden and the UK – are also among the top ten donors of ODA in 2018. However, a number of smaller donors also feature among the top ten, contributing a larger proportion of their total ODA. It is also notable that a number of the largest donors of ODA – the US, Germany, Japan, France, Italy and the Netherlands – reported less than 0.2% of their total ODA going to GBV in 2018.

The OECD DAC also tracks ODA focusing on gender equality more broadly using the gender equality policy marker (GEM). Although the GEM includes all gender equality programming, not only that specifically targeting GBV, it gives some context for how funding for GBV fits within the wider funding climate for gender equality programming. It is also relevant because development programmes often treat GBV as one element of broader gender equality programming, whilst the ‘violence against women and girls’ purpose code only captures aid reported as having a primary focus on GBV. At the same time, the GEM has limitations due to inconsistent and incomplete donor reporting. [17] In 2018, DAC donors reported that only 8% of ODA had a primary focus on gender equality. An additional 25% of ODA made a partial contribution towards gender equality. [18]

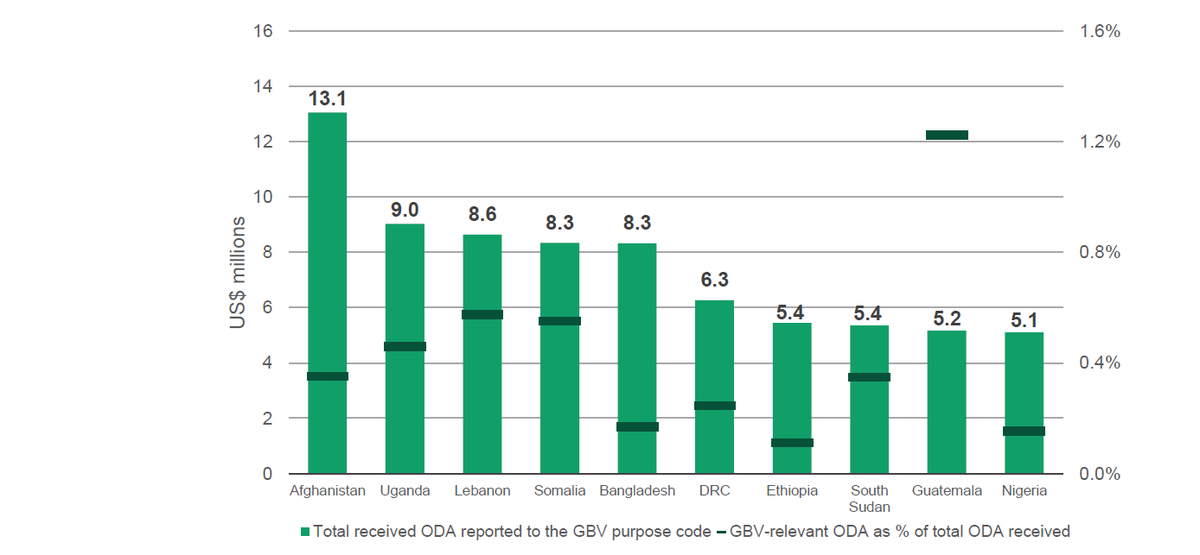

Figure 2: Top ten recipients of GBV-relevant ODA in 2018

Top ten recipients of GBV-relevant ODA in 2018

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Creditor Reporting System (CRS).

Notes: Data is in constant 2017 prices. Figures only include projects reported to the CRS by donors and coded with the purpose code 15180 – ending violence against women and girls. Figures include country-allocable aid only. Total ODA refers to total gross bilateral ODA as recorded in the CRS. DRC: Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Figure 2 shows the top ten recipients of ODA targeting GBV. This includes a number of conflict-affected countries where violence against women is well documented: Afghanistan, Somalia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Sudan and Nigeria. It also includes several countries with large refugee populations within which GBV has been a prominent concern – including Lebanon, Bangladesh and Ethiopia – although the extent to which assistance is connected to crisis response is unclear.

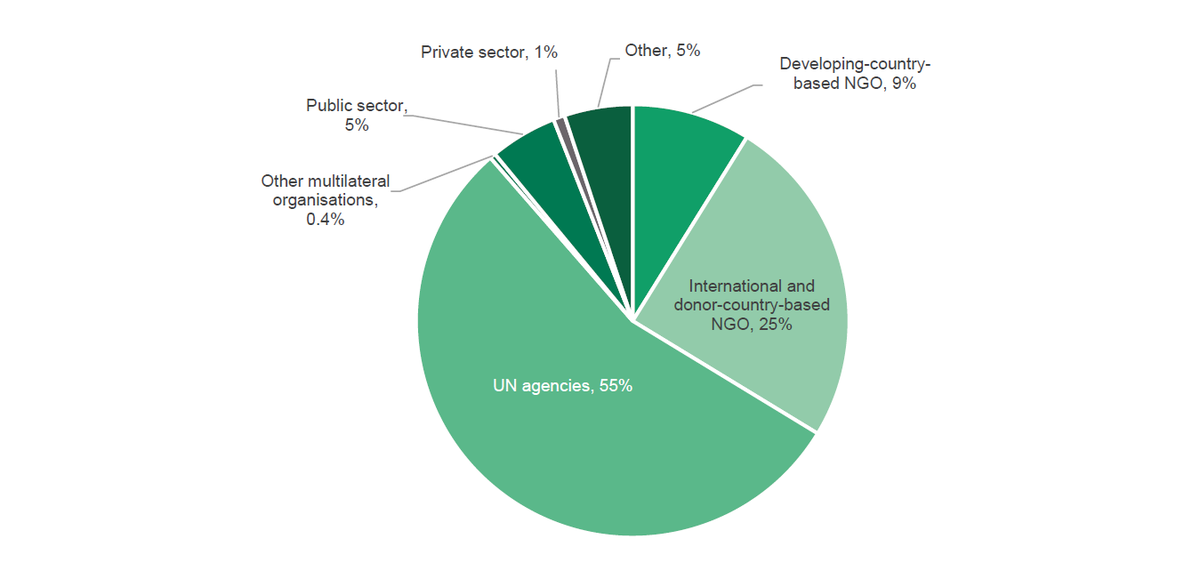

As illustrated in Figure 3, ODA focused on GBV is channelled primarily through UN agencies and international NGOs in contrast to the general trend of channelling development assistance through national governments. More than half of aid focused on GBV is channelled through UN agencies (55% compared with 11% for total ODA) and 25% channelled to international NGOs and donors (compared with 11% for total ODA). Only 5.0% of ODA focused on GBV is channelled through the public sector. In addition, developing-country-based NGOs receive a larger share of aid targeting GBV (8.9%) when compared with the general trend for ODA (1%).

Figure 3: Channels of delivery of GBV-relevant ODA in 2018

Channels of delivery of GBV-relevant ODA in 2018

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Creditor Reporting System (CRS).

Notes: Data is in constant 2017 prices. Figures only include projects reported to the CRS by donors and coded with the purpose code 15180 – ending violence against women and girls. Channel of delivery refers to the first implementing partner of the ODA activity. OECD DAC coding was used to classify NGOs. International NGOs are organised on an international level. Some international NGOs may act as umbrella organisations with affiliations in several donor and/or recipient countries. Donor-country-based NGOs are organised at the national level, based and operated either in the donor country or another developed (non-ODA eligible) country. Developing-country-based NGOs are organised at the national level, based and operated in a developing (ODA eligible) country.

Global funds focusing on GBV

In addition to regional and country-based finance for GBV programmes, there are a number of global pooled funds that are relevant to GBV (see Appendix 3). Two new vehicles focusing on crisis contexts have the explicit aim of filling gaps across the triple nexus: the Women’s Peace and Humanitarian Fund (WPHF), which supports women’s organisations to work on a range issues across the WPS agenda and humanitarian action (not only GBV); and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)’s Humanitarian Action Thematic Fund, which is a mechanism to provide more flexible funding to UNFPA to lead the GBV ‘Area of Responsibility’ in crisis settings.

To date, the crisis-focused funds have attracted relatively small investment. For example, the UN’s Multi-Partner Trust Fund for Action Against Sexual Violence in Conflict, which has a major focus on strengthening the rule of law response to sexual violence in conflict, has received an average of only US$4 million per year since 2007 [19] and the recently launched WPHF has received an average of US$6 million per year over 4 years. [20] The Spotlight Initiative, a joint EU and UN initiative launched in 2017 with €500 million in seed funding from the EU, is a significant, recent, larger scale effort to address all forms of GBV. However, it does not target conflict or emergency settings.

Coordination of GBV programmes across the nexus

Development and humanitarian actors have different approaches to coordination. This impacts the way in which they relate to one another in crisis situations and how the various agencies and actors involved in delivery of GBV programmes coordinate with one another. In humanitarian crises, UN OCHA takes on much of the burden of coordination, and there are strong financial incentives for agencies to participate in HRPs in order to receive funding. Within the humanitarian cluster system, GBV is an ‘Area of Responsibility’ that falls under the protection sector. At the global level, UNFPA leads the GBV ‘Area of Responsibility’ and at the country level it leads GBV coordination. In refugee contexts, the UNHCR has the mandate to protect refugees and to coordinate the refugee response, including overseeing the GBV response.

In contrast to the strong role of international agencies in humanitarian coordination, national governments usually lead the coordination of development assistance. Development actors participate in sector or thematic coordination mechanisms linked with national strategies; however they also face disincentives to coordinate. Their interests, in terms of securing funding and access, are often better served by building close bilateral relationships with national authorities. This poses particular challenges in fragile settings. If governance is weak, so is the government’s leadership of sector coordination mechanisms and its ability to ensure policy coherence – thus, coordination of development work is also weak. [21] Because development support is aligned with government institutions, policies and strategies, the government institutions tasked with leading GBV vary from context to context and coordination structures are diverse.

In contexts in which humanitarian, development and/or refugee operations are simultaneous, there may be parallel or overlapping coordination structures. For example, in mixed situations with both refugees and internally displaced people, there may be both humanitarian and refugee coordination systems in place, focusing on different target populations or geographic areas. [22] In addition, the role of various agencies may vary depending upon their capacity and resources. For example, in contexts in which UNFPA lacks resources to coordinate the GBV sub-cluster, it may delegate this to an international NGO.

Downloads

Notes

-

1

ODA and humanitarian assistance are increasingly channelled to the same protracted crises. Development Initiatives, 2019. Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2019. /publications/global-humanitarian-assistance-report-2019/Return to source text

-

2

The WPS agenda is guided by 10 UN Security Council resolutions: 1325, https://undocs.org/en/S/RES/1325(2000); 1820, https://undocs.org/en/S/RES/1820(2008); 1888, https://undocs.org/en/S/RES/1888(2009); 1889, https://undocs.org/en/S/RES/1889(2009); 1960, https://undocs.org/en/S/RES/1960(2010; 2106, https://undocs.org/en/S/RES/1960(2010); 2122, https://undocs.org/en/S/RES/2122(2013); 2242, https://undocs.org/en/S/RES/2242(2015); 2467, https://undocs.org/en/S/RES/2467(2019); and 2493, https://undocs.org/en/S/RES/2493(2019) .Return to source text

-

3

Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), 2013. Centrality of Protection in Humanitarian Action. Available at: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/principals/content/iasc-principals-statement-centrality-protection-humanitarian-action-2013Return to source text

-

4

IASC, 2015. Guidelines for Integrating Gender Based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Action. Available at: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/working-group/documents-public/iasc-guidelines-integrating-gender-based-violence-interventionsReturn to source text

-

5

Gender-Based Violence Area of Responsibility (UNFPA), 2019. Handbook for Coordinating GBV in Emergencies. Available at: https://gbvaor.net/sites/default/files/2019-07/Handbook%20for%20Coordinating%20GBV%20in%20Emergencies_fin.pdfReturn to source text