Introduction

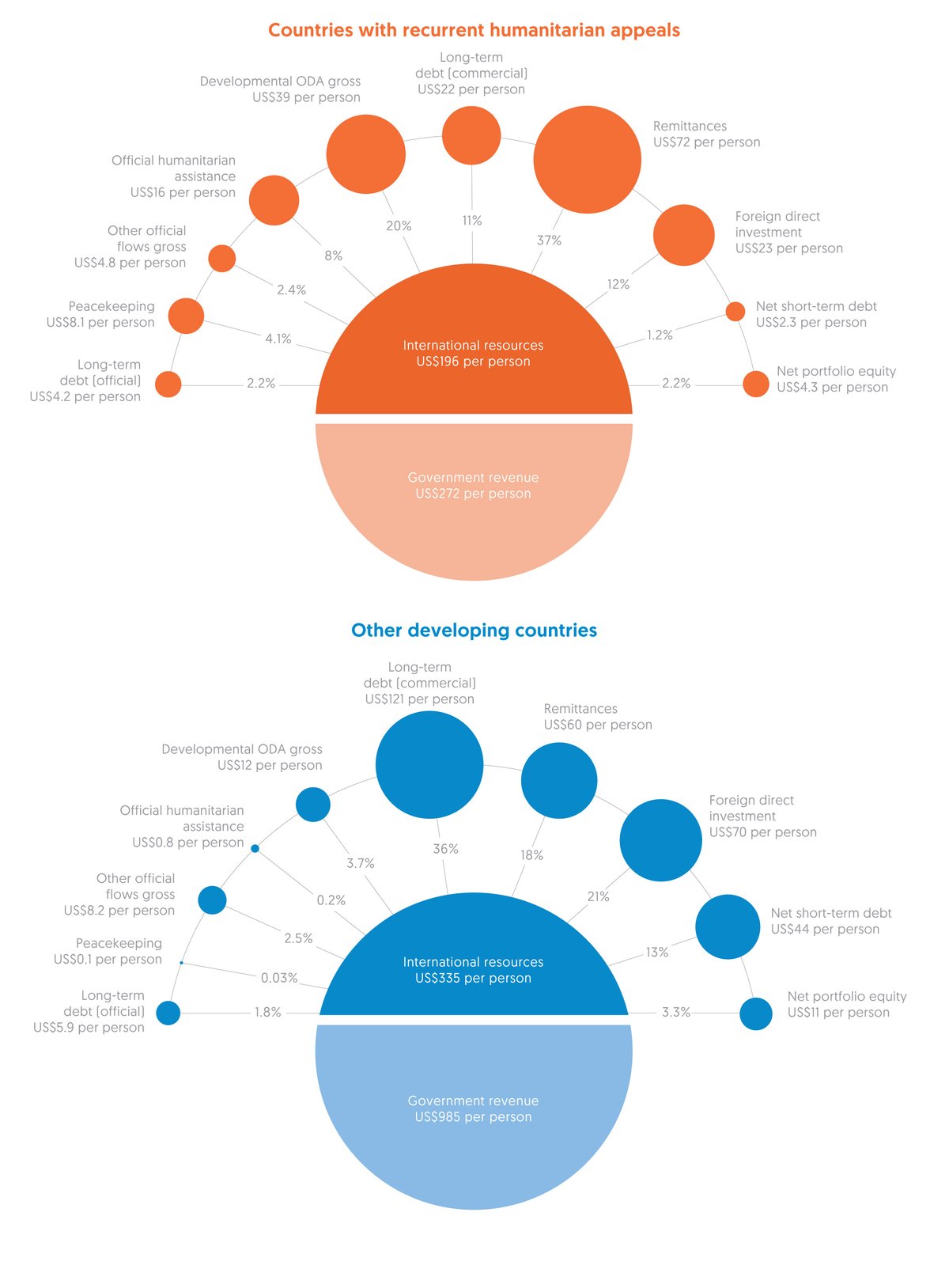

Many crises are protracted and complex, with needs beyond what the official humanitarian response alone can finance. It is crucial therefore to draw on the potential of a wide range of complementary, domestic and international, public and private, resources. However, in countries with appeals in both 2017 and for one or more of the preceding years, official domestic resources are, on average, significantly lower than in other developing countries (US$272 per person compared with almost US$1,000) while international flows per person are over 40% lower.

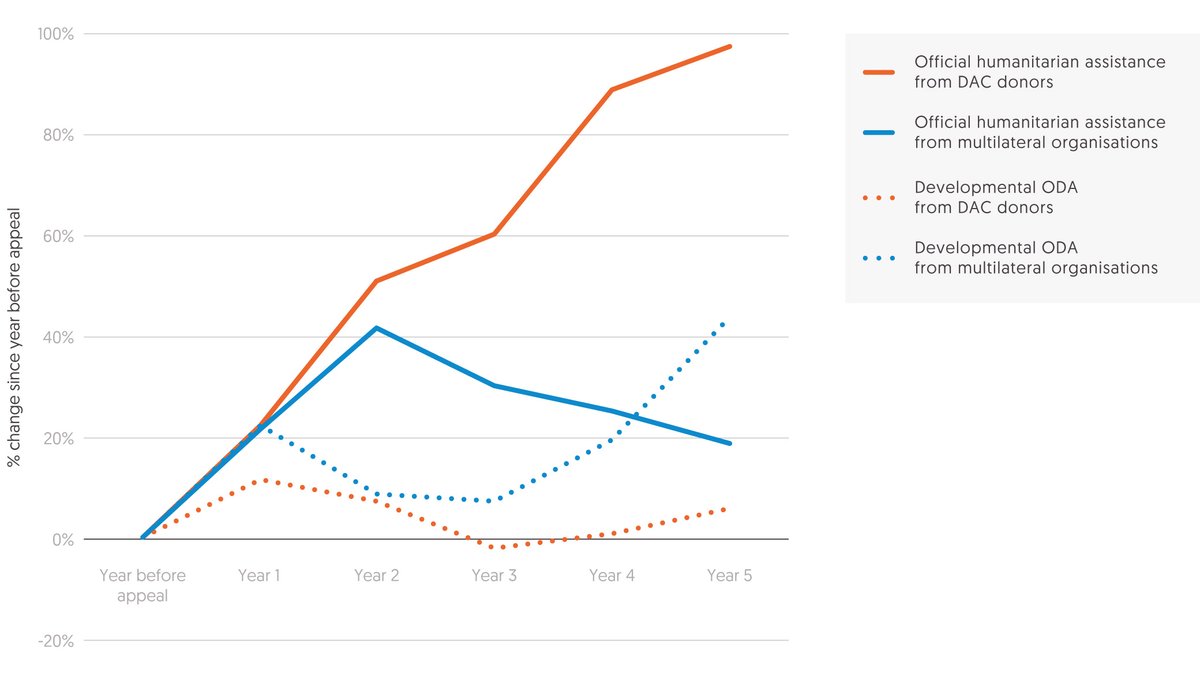

Developmental official development assistance (ODA less humanitarian assistance) and official humanitarian assistance respond differently at different times in protracted crisis contexts. In aggregate, from the year before an appeal to the fifth consecutive year of the appeal, humanitarian assistance grows at a much faster rate than developmental ODA (by 88% compared with 14%) to crisis countries. Response differs by actor: humanitarian assistance grows much faster from Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donors than multilateral organisations (up 98% compared with 19%), while developmental ODA grows much faster from multilateral organisation than DAC donors (up 43% compared with just 6%). However, these aggregate trends mask significant differences at country level. Of 27 protracted crisis response countries (see Chapter 1, Box 1.1), 6 received less overall aid in the fifth year of crisis response.

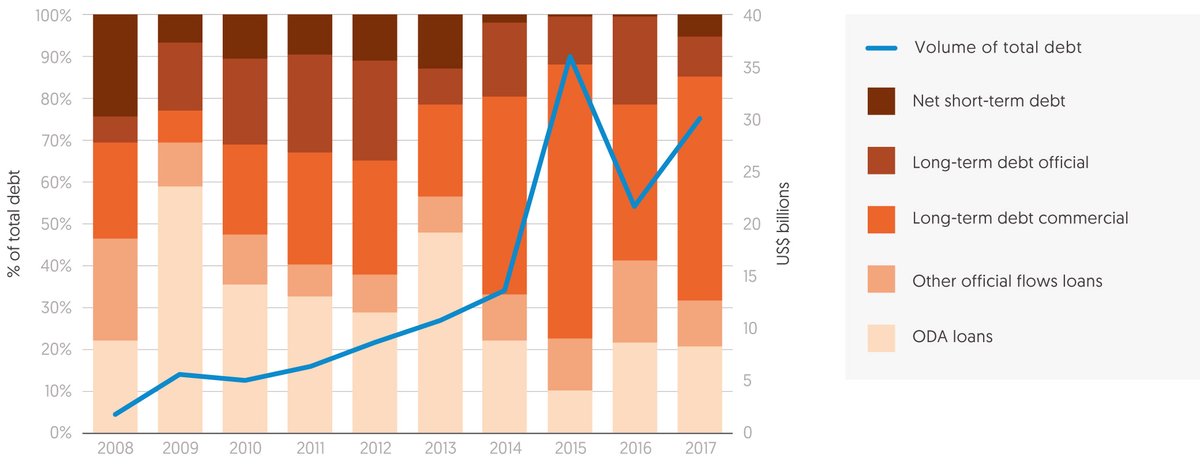

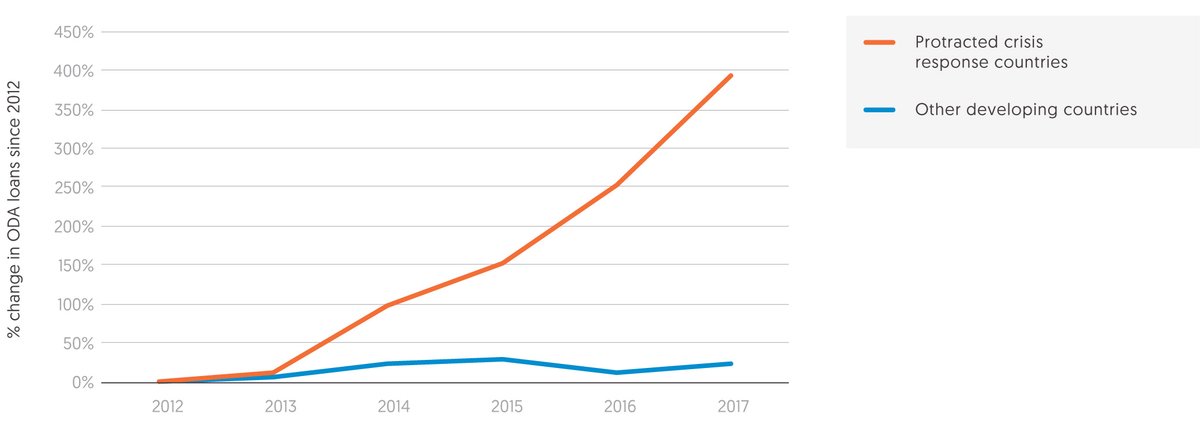

Developmental ODA is increasingly being delivered as loans. In fact, protracted crisis response countries are receiving significantly more lending of all kinds. Between 2012 and 2017, ODA loans grew nearly four-fold, at almost ten times the rate to other developing countries. This lending was not evenly distributed: in 2017, 75% of ODA loans went to just 7 of 34 protracted crisis response countries, with many others receiving little or no lending of this kind. The extent to which recipients are able to manage this debt is important. Loans to countries with recurrent appeals and assessed as at moderate or high risk of debt distress were less concessional than to other developing countries.

Crisis can impact on the ability of the private sector to operate effectively, and to thereby contribute to long-term development. Foreign direct investment (FDI) can be volatile, decreasing on average by 47% in the first year of crisis for countries with five or more years of consecutive UN-coordinated appeals. Protracted crisis also impacts the domestic private sector, with its size as a share of GDP in 2017, in 12 countries with more than five consecutive humanitarian appeals, less than a third that of other developing countries. Notwithstanding this, the private sector has a role to play in responding to crisis. For example, through the range of risk financing mechanisms that have been developed based on pre-agreed triggers to release financing.

Resources beyond humanitarian assistance

Figure 3.1: Both domestic and international resources are lower per person in countries in crisis

Resource mix per person to countries with recurrent humanitarian appeals compared with other developing countries, 2017

Resource mix per person to countries with recurrent humanitarian appeals compared with other developing countries

Source: Development Initiatives based on Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC), UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Financial Tracking Service (FTS), UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF), UN Conference on Trade and Development, World Bank and International Monetary Fund data and data from peacekeeping budgets or funding snapshots.

Notes: Government revenue may include grants for Turkey and Yemen. Negative flows for net portfolio, short-term debt and foreign direct investment have been set to zero at country level. Countries with recurrent appeals include 24 countries with two or more consecutive years of appeals in 2017. Developmental ODA gross captures all gross ODA disbursements except for humanitarian purpose codes.

International humanitarian assistance is a critical resource for responding to the needs of people affected by crisis, but a wide range of other domestic and international resources can and do complement humanitarian assistance and developmental ODA (ODA less humanitarian assistance). Domestic resources play a significant role in the overall financing mix for all developing countries, with governments acting as key primary responders, using their own revenues, in countries in crisis.

However, countries with recurrent UN-coordinated appeals in 2017 – those with appeals in 2017 and consecutively for at least one preceding year – have significantly lower official domestic resources per person and these account for a smaller proportion of total resources available. Such countries also have significantly lower levels of commercial inflows per person but receive more developmental ODA.

- Compared with international inflows of finance in aggregate, domestic public resources (non-grant government revenues) account for a lower share of available financing in countries with recurrent appeals than other developing countries.

- In countries with recurrent appeals, non-grant government revenues are on average around a quarter (28%) of that in other developing countries, at US$272 per person, compared with almost US$1,000.

International inflows too – except for developmental ODA and humanitarian assistance – despite their larger proportional significance, are on average smaller in countries with recurrent appeals than other developing countries. This trend is consistent across income group categories, although less noticeable in poorer countries. In aggregate commercial inflows per person are over 40% lower in countries with recurrent appeals than other developing countries.

- Developmental ODA and humanitarian assistance account for much larger proportions of international inflows for countries with recurrent appeals. In 2017, developmental ODA accounted for a fifth (20%) of all international inflows for such countries (compared with 3.7% in other developing countries) and official humanitarian assistance accounted for 8% (compared with 0.2%).

- In volume terms, countries with recurrent appeals received triple the amount of developmental ODA per person compared with other developing countries.

- There is a particularly marked difference in aid levels to the two upper middle income countries with recurrent appeals in 2017, reflecting reconstruction efforts. Iraq and Libya received an average of US$46.23 developmental ODA per person: over five times more than other upper middle income countries (which averaged US$8.48 per person).

- In contrast, there is much less difference in aid volumes per person between crisis and non-crisis low income countries (LICs), with LICs with recurrent appeals receiving US$52.76 per person and other LICs US$45.12 per person.

- In countries with recurrent appeals, commercial sources of financing are comparatively low, accounting for 26.6% of all international inflows, compared with 73.8% in other developing countries.

- Of these sources of commercial financing, three times the per person volume of FDI flowed to other developing countries than countries with recurrent appeals: US$70.48 compared with US$23.32.

- In contrast to aid, LICs with recurrent appeals received particularly low amounts of FDI compared with their non-crisis counterparts: US$13.68 per person, half the US$27.05 per person in other LICs.

ODA to protracted crisis response countries

Figure 3.2: DAC donors drive growth in humanitarian assistance to protracted crises, while multilateral organisations drive slower increases in developmental ODA

% change in official humanitarian assistance and developmental ODA by donor type for protracted crisis response countries

% change in official humanitarian assistance and developmental ODA by donor type for protracted crisis response countries

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD DAC and UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) data.

Notes: Data is shown for 27 countries with at least 5 consecutive years of UN-coordinated humanitarian country response plans between 2000 and 2017 (with 2017 being the latest year for which country-level development finance data is available). Debt relief to all countries was excluded from the official development assistance (ODA) figures for all years as, while important in freeing up fiscal space, it does not represent a transfer of resources.

Crises are becoming increasingly protracted and complex, exacerbating insecurity and longer-term livelihood needs and demanding longer-term developmental responses to address these needs and help resolve underlying causes of crisis (see Chapter 1, Figures 1.1 and 1.2). As a result, developmental ODA (ODA less humanitarian assistance, and which includes ODA to conflict, peace and security) and humanitarian assistance are progressively being channelled to the same crisis contexts. Consequently, the drive to ensure that developmental ODA and humanitarian assistance are closely coordinated and complementary as a prerequisite for development effectiveness has gained significant momentum. Most notably this is through the recently agreed OECD DAC 2019 recommendation on the humanitarian-developmentpeace nexus. [1] This sets the agenda for pursuing “development where possible and humanitarian only when necessary” to address longer-term developmental needs in protracted crisis contexts.

Figure 3.2 illustrates how developmental ODA and humanitarian assistance interact in practice in protracted crises, and evidences this debate. It compares, in aggregate, how the contributions of humanitarian assistance and developmental ODA from DAC donors and multilateral organisations have varied over the first five years of a crisis response, to 27 countries with 5 or more consecutive years of UN-coordinated appeals between 2000 and 2017.

In aggregate, humanitarian assistance is observed to grow at a much faster rate than developmental ODA from the year before appeal to the fifth consecutive year of a crisis response. These aggregate totals mask marked difference in the funding behaviour of bilateral DAC donors and multilateral donors for allocations of humanitarian assistance and developmental ODA. Contributions of humanitarian assistance from DAC donors grow consistently, and at a faster rate than those from multilateral organisations. Conversely, contributions of developmental ODA from DAC countries rise only slightly by the fifth year of crisis response, while contributions from multilateral organisations grow more markedly. These aggregate trends in total humanitarian assistance and developmental ODA also mask considerable variation at country level in volumes of funding across the years of the crisis response.

- From the year before an appeal to the fifth year of crisis response, total humanitarian assistance to 27 protracted crisis response countries increases by 88% with developmental ODA rising by just 14%.

The growth in humanitarian assistance is seen to be driven by consistent year-on-year increases in funding from OECD DAC donors. While by Year 5 contributions from multilateral organisations are higher than the year before appeal, initial year-on-year growth over this period is not sustained.

- The total amount of humanitarian assistance increases year on year during the first five years of protracted crisis response. DAC donors account for the majority of this growth, increasing their contributions by 98% (from US$3.9 billion to US$7.8 billion across the 27 protracted crises). Disbursements from multilateral organisations rise 19% (from US$576 million to US$686 million) over this period but contributions decrease year on year in Years 3, 4 and 5.

- By the fifth year of crisis, DAC donors’ contributions grow from 87% of total humanitarian assistance in the year before appeal to 92%.

In contrast to humanitarian assistance, by the fifth year of crisis response, bilateral contributions of developmental ODA from DAC donors increase at a much lower rate, up by 6% relative to the year before the crisis response, while contributions from multilateral organisations grow by over two fifths (43%).

- Between the year before appeal and the fifth year of crisis response, allocations from DAC donors reduce as a proportion of total developmental ODA from 77% to 72%. The total volume of assistance increases slightly (6%, from US$15.6 billion to US$16.5 billion) over this period, but year-on-year growth is not consistent, with falls in Years 2 and 3 of the crisis response.

- Disbursements of developmental ODA from multilateral organisations increase more than those from DAC donors, rising 44% from US$4.5 billion in the year before appeal to US$6.5 billion in the fifth year of crisis response. As with DAC donors, year-on-year growth is not consistent, with falls also in Years 2 and 3, but these are counterbalanced by larger rises in Years 4 and 5.

Further investigation is needed to understand the factors underpinning these funding trends and the roles that different financing mechanisms and decision-making structures play in this. This would help to generate lessons on the role of development actors in crisis and how their engagement can be sustained to address longer-term development needs.

The extent to which developmental ODA and humanitarian assistance, at country level, complement one another and support responses to crisis, requires an understanding of several factors. Among these are the location of crisis, geographical targeting of projects and the extent to which pre-existing development projects continue to be financed with the onset of crisis and whether new development projects are initiated. Where assistance is being targeted by sector is also important. Aggregate analysis of sector allocations suggests that some complementarity of developmental ODA and humanitarian assistance may be occurring.

- Developmental ODA to social infrastructure and services in 27 countries with 5 or more consecutive years of UN-coordinated appeals between 2000 and 2017 grew by more than a quarter (27%), from an aggregate of US$9.9 billion in the year before appeal to US$12.6 billion in the fifth year of crisis response. Such social infrastructure and services includes water, sanitation and hygiene, education, health and other social service sectors, alongside governance and security sectors. This suggests funding that might complement, or have the potential to complement, humanitarian assistance, which is likely to also focus on water, sanitation and hygiene, education and health.

Recipient country trends

The sharp growth in humanitarian assistance and much-less-pronounced growth in developmental ODA to protracted crisis response countries is not consistently seen across recipient countries. Understanding individual country contexts is therefore critical, including the level of need, scale of requirements and state of the crisis. Of 27 protracted crisis response countries, 6 received less overall aid (humanitarian assistance and developmental ODA combined) in the fifth year of crisis response compared with the year before the crisis response. [2]

- The extent of change in combined volumes of funding among these six countries varied greatly, falling by 76% in Côte d’Ivoire, 46% in Indonesia, 44% in Guinea, 37% in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPR Korea), 31% in Afghanistan and 15% in Mauritania.

The funding data shows that most countries receive more developmental ODA, however more than a quarter receive less. Of the 27 countries, 8 received less developmental ODA in the fifth year of crisis compared with the year before appeal, with large decreases, in excess of US$1.0 billion, in two countries.

- Developmental ODA reduced markedly to Afghanistan, by US$1.8 billion (32%), to Indonesia by US$1.2 billion (44%) and to Côte d’Ivoire by US$856 million (80%) by the fifth year of their appeal.

- Five other countries receiving less developmental ODA by the fifth year of crisis saw significant proportional decreases but these represented much smaller falls by volume. These were Guinea, by 37% (US$135 million), Mauritania, by 23% (US$81 million), Chad, by 20% (US$61 million) and Somalia, by 19% (US$19 million).

- Debt relief, while not constituting a transfer of resources, can still ease the burden on protracted crisis response countries. Debt relief to 27 protracted crisis response countries grows initially from the year before appeal from 6% (US$1.5 billion) of total ODA to these countries, peaking in Year 3 at 15% (US$4.9 billion) before reducing in Years 4 and 5 of the crisis response, to account for 1% (US$417 million) in the fifth year of crisis response.

Conversely, six countries received in excess of US$500 million more developmental ODA in the fifth year of crisis response than in the year before appeal, with allocations to two increasing by more than US$1.0 billion.

- Allocations to Kenya more than doubled (141% increase), rising by US$1.8 billion by the fifth year of appeals. Disbursements to Myanmar were almost four times as large, rising by US$1.0 billion (295% increase). Contributions to South Sudan (up by US$833 million), Angola (US$705 million) and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (US$695 million) all increased by more than US$500 million between the year before appeal and the fifth year of crisis response.

A similar picture of variation in levels of funding at country level over the years of crisis response is also evident for humanitarian assistance with most countries receiving more by the fifth year of crisis compared with the year before the crisis, but a quarter receiving less.

- Of the 27 countries with 5 consecutive years of protracted crisis response, 7 received less humanitarian assistance in the fifth year than in the year before appeal. Indonesia received 84% less (down US$144 million), Guinea 77% (US$58 million), DPR Korea 49% (US$117 million), Tajikistan 35% (US$15 million), Afghanistan 24% (US$131 million), Djibouti 15% (US$3 million), and DRC 7% (US$35 million).

Loans to protracted crisis response countries

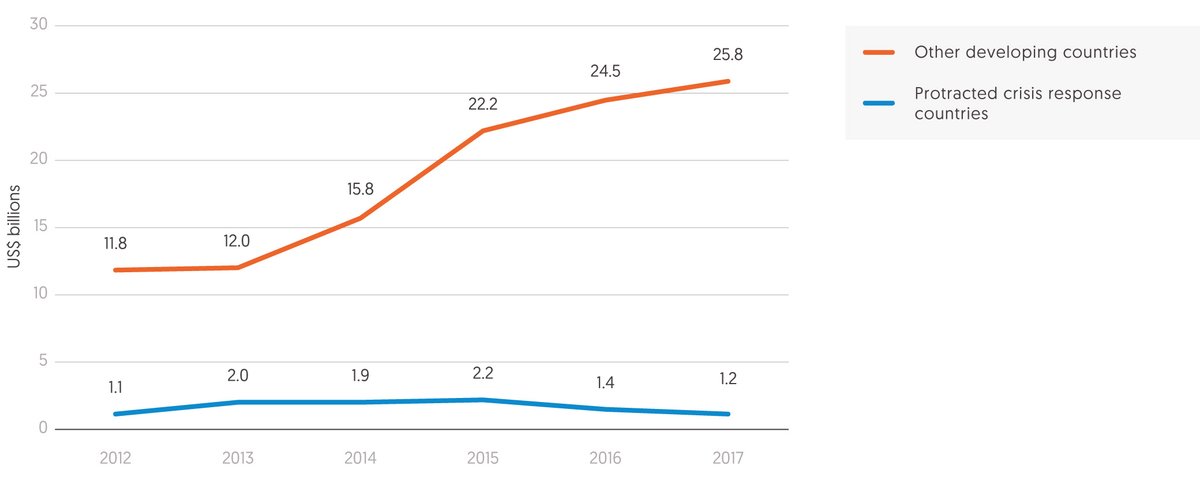

Figure 3.3: Total lending to protracted crisis response countries is growing rapidly

Total lending to protracted crisis response countries, 2008–2017

Total lending to protracted crisis response countries, 2008–2017

Source: Development Initiatives based on World Bank International Debt Statistics and OECD DAC data.

Notes: Data is analysed for 34 protracted crisis response countries – these had at least five consecutive years of humanitarian response plans between 2000 and 2019. Data is included in the chart for all years in which these 34 countries had a humanitarian appeal.

Lending to countries in crisis is increasing. Over the last decade volumes of both public and commercial lending to countries with five or more consecutive years of UN-coordinated appeals have increased more rapidly than lending to non-crisis countries. Growth in long-term commercial lending has been particularly substantial such that by 2017 it accounted for more than half of all lending to such countries, compared with 23% in 2008.

However, a small number of recipients are receiving the majority of lending with many protracted crisis response countries receiving little. The aggregate trends therefore relate to patterns of lending to a small number of countries.

- Total lending to protracted crisis response countries has increased almost 18-fold over the decade, from US$1.7 billion in 2008 to US$30.0 billion in 2017. The pattern of consistent growth was only interrupted in 2015, when Ukraine experienced a spike in long-term commercial debt of US$19.4 billion, in its first year with an appeal. This compares with growth to other developing countries over the same period of just 129%, from US$550 billion to US$1,258 billion.

- This increase in total lending to protracted crisis response countries was primarily driven by long-term commercial debt, increasing from US$0.4 billion in 2008 to US$15.9 billion in 2017. ODA and other official flow loans also grew significantly, increasing from US$0.4 billion each in 2008 to US$6.3 billion and US$3.3 billion in 2017, respectively.

- A smaller subset of recipients is driving this increase in total lending to protracted crisis response countries, with two noticeable patterns. Firstly, some countries such as Nigeria, Iraq and the Ukraine attracted a much larger amount of lending before the crisis and subsequently entered a protracted crisis response in recent years, and lending has continued. Secondly, other countries, including Burkina Faso, Djibouti and Yemen, received increases in total lending as or after the crisis response began.

Figure 3.4: Concessional lending to protracted crisis response countries is growing much faster than that to others, but is driven by a limited number of countries

% change in ODA loans to protracted crisis response countries and other developing countries, 2012–2017

% change in ODA loans to protracted crisis response countries and other developing countries, 2012–2017

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD DAC and UN OCHA FTS.

Notes: Data was analysed for 34 protracted crisis response countries – these had at least five consecutive years of humanitarian response plans between 2000 and 2019 (with 2017 being the latest year for which country-level development finance data is available). Data is included in the chart for all years in which these 34 countries had a humanitarian appeal. Debt relief is subtracted in the case of debt reorganisation to account for new loans being issued as replacement for old loans that are written off.

Concessional loans have been part of the aid financing landscape for decades – both from DAC donors and the World Bank or regional development banks. Since 2008 there has been an increase in the use of loans as a form of aid to developing countries. Loans made up 17% of total ODA in 2008, rising to 26% in 2017.

Concessional lending to protracted crisis response countries, like total lending, is also growing. The growth in ODA loans is, however, targeted to a small number of countries, with some others receiving little or no lending. The group receiving higher volumes of ODA loans includes both countries that have continued to receive significant lending as they have begun a protracted crisis response, and those already with UN-coordinated appeals to which more lending has subsequently been directed.

- ODA loans to other developing countries rose by 40% between 2012 and 2017, but in aggregate such loans to protracted crisis response countries increased nearly four-fold over the same period.

- This rise is from a low base, however, as before 2012 very few loans were made to protracted crisis response countries. So while overall volumes of ODA loans to these countries are small, they are increasing at a much faster rate than to other developing countries, growing from 7% of total ODA loans in 2012 to 14% in 2017.

However, a small number of protracted crisis response countries received a disproportionately large share of all ODA loans in 2017, while others continued to receive very low levels of lending.

- The seven largest recipients of ODA loans among countries in, or entering, protracted crisis response in 2017 accounted for 75% of all loans to protracted crisis response countries.

- In 2017, Nigeria received the largest volume of ODA loans (US$1.1 billion; 18% of all ODA loans to protracted crisis response countries), followed by Iraq (US$847 million, 14%), Cameroon (US$757 million, 12%), Yemen (US$557 million, 9%), Senegal (US$491 million, 8%), Myanmar (US$430 million, 7%) and Niger (US$413 million, 7%). All these countries received over 27% of their ODA as loans, with Cameroon receiving the greatest proportion among these seven, at 58%.

- Of these seven countries, Niger, Senegal and Yemen were categorised as LICs, Myanmar, Nigeria and Cameroon as lower middle income countries and Iraq as an upper middle income country in 2017.

- Since 2012, South Sudan has had the largest increase in ODA loans of all protracted crisis response countries, increasing 40-fold from US$1.74 million to US$72.05 million in 2017. However, while a large proportional increase, loans have accounted for a very small share of ODA, increasing from 0.2% to 3.3% between 2012 and 2017.

- In 2017, of twenty-one countries that still had a protracted crisis response that year, eight received less than US$100 million in ODA loans, of which two received less than US$50 million and three no ODA loans at all.

Most of these ODA loans to protracted crisis response countries, by volume, were disbursed from multilateral organisations. While the volume of loans has grown significantly from 2012 to 2017, the share of total loans between DAC donors and multilateral organisations has not changed greatly, except for in 2013.

- Between 2014 and 2017 loans from multilateral organisations accounted for between 66% and 70% of all ODA loans to protracted crisis response countries.

- Concessional lending from DAC donors accounted for a larger share of ODA loans to other developing countries than to protracted crisis response countries, making up between 41% and 43% from 2012 to 2017.

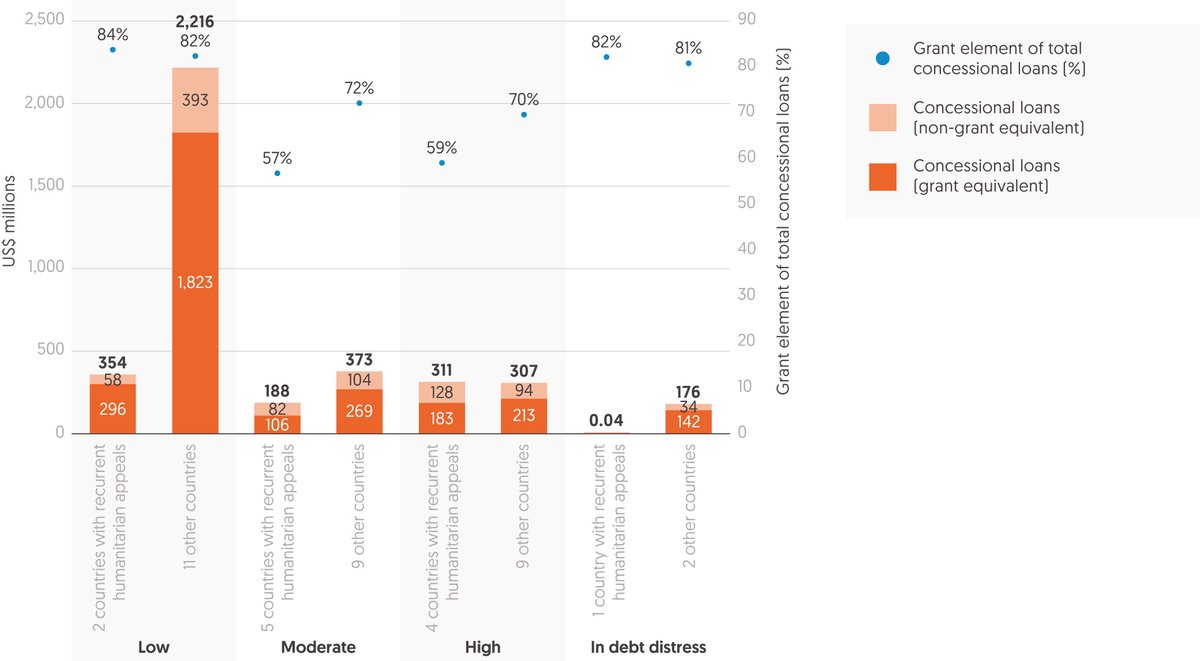

Figure 3.5: When debt risk is moderate or high, loans are less concessional to countries in crisis than other countries

Volume and concessionality of ODA loans to countries with recurrent appeals and other developing countries by risk of debt distress, 2017

Volume and concessionality of ODA loans to countries with recurrent appeals and other developing countries by risk of debt distress, 2017

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD DAC Creditor Reporting System (CRS) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) data.

Notes: Countries with recurrent appeals are those with a UN-coordinated appeal in 2017 and consecutively for at least one preceding year. Data is only included for the 43 countries that received ODA loans in 2017 and had a debt sustainability analysis in the IMF Risk of Debt Distress classification for low income countries as of 31 July 2019.

The right financing mechanisms and modalities need to be used in the right contexts. A strong evidence base is needed to understand how loans are being used and targeted, and their impact on vulnerable people and people affected by crisis. Understanding the extent to which recipients are able to manage debt is an important element of this evidence, in light not only of the increase in concessional lending but also the pronounced growth in total lending to countries with humanitarian appeals.

Figure 3.5 compares countries which have been categorised as in debt distress, highlighting the volume of lending in 2017 by category of debt distress and the proportion of grant element in the loans – that is, how concessional the loans are. [3] Comparing countries with recurrent UN-coordinated appeals in 2017 with other developing countries highlights that a higher proportion of concessional loans to countries with recurrent appeals went to those with moderate and high levels of debt distress than to other developing countries.

- 42% (US$853 million) of loans to countries with recurrent appeals went to countries with a debt risk categorisation, compared with just 15% (US$3.1 billion) of loans to other developing countries.

- Most lending (72%) to other developing countries in debt distress in 2017 went to those categorised as low risk, compared with 42% for countries with recurrent appeals.

- A higher proportion of lending to countries with recurrent appeals went to those assessed as being in moderate and high risk of debt distress, at 22% and 36% respectively, compared with 12% and 10% for other developing countries.

Loans to countries assessed as at moderate or high risk of debt distress were less concessional for countries with recurrent appeals.

- The grant elements for concessional lending to countries with recurrent appeals in 2017 and assessed as being at moderate or high levels of debt distress were 57% and 59% of the loan totals, compared with 72% and 70% for other developing countries.

- Of the lending going to those countries not identified as in debt distress, the proportion of grant element was similar in countries with recurrent appeals (57%) and in other developing countries (58%).

Cameroon, Myanmar and Senegal were the three recurrent crisis response countries with recent assessments of debt distress and which received the largest volumes of concessional loans in 2018 (all in excess of US$150 million).

- Senegal and Myanmar were categorised as being at low risk and received a high proportion of loans with a grant element, 78% and 88% respectively, broadly consistent with the average of 84%. However, Cameroon was considered to be at high risk of debt distress but received a lower proportion of loans with grant element, at 59%.

- Of recurrent crisis response countries not classified as being in debt distress, Nigeria, which received US$175 million in loans in 2017, received a notably lower level of grant element, at 39%.

Foreign direct investment to crisis contexts

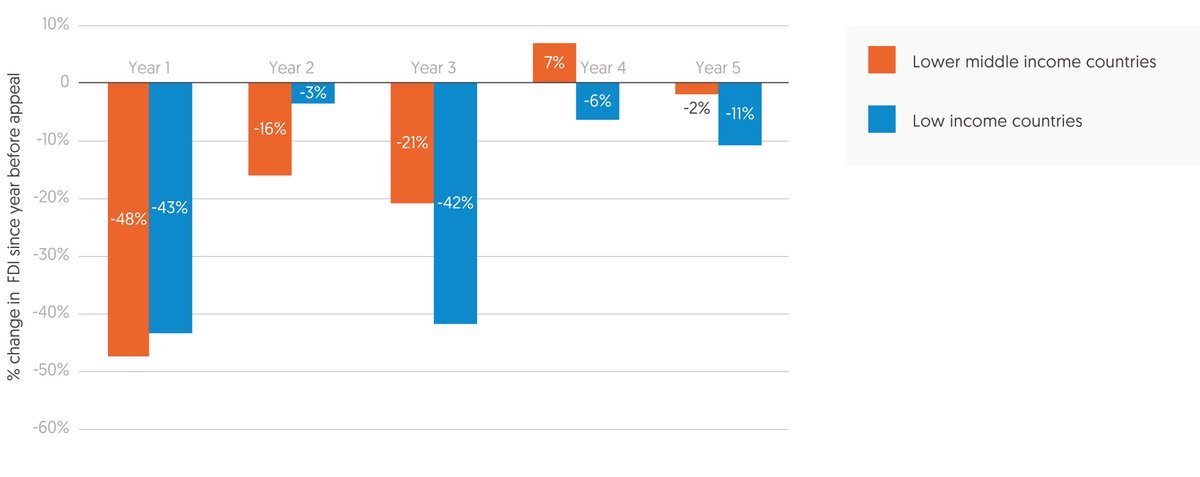

Figure 3.6: Foreign direct investment is volatile and inflows can fall rapidly in the early years of a protracted crisis response

% change in FDI to protracted crisis response countries, compared with volume received in the year before appeal, by income group

% change in FDI to protracted crisis response countries, compared with volume received in the year before appeal, by income group

Source: Development Initiatives based on UN Conference on Trade and Development and World Bank data.

Notes: FDI: foreign direct investment. Data for 27 protracted crisis response countries – these had at least 5 consecutive years of humanitarian response plans between 2000 and 2017 (with 2017 being the latest year for which country-level development finance data is available). Data is in constant 2017 prices.

With traditional sources of finance under pressure, much attention is being given to the role of the private sector across the humanitarian and development sectors, including the role of blended finance. For instance, the International Finance Corporation has set a target for 40% of its investments to target fragile and conflict-affected countries by 2030. However, volumes in crisis and fragile contexts remain small, where blended approaches require particular transparency to avoid undermining public investments and widening disparities. [4] Public finance, both domestic and international, remains crucial and can work to build resilient private sectors in crisis-affected countries. Donors can assist by supporting strong enabling environments.

Small volumes and proportions of FDI go to the poorest countries, but, relative to the size of their economies, these are nevertheless important for some.

- Less than 1.5% of all FDI to developing countries (excluding China) goes to LICs. [5]

- However, as a share of GDP, FDI has been consistently higher for LICs than developing countries more broadly, standing at 2.8% in 2017 compared with the developing country average of 2.3%.

Assessment of 27 protracted crisis response countries – with five or more consecutive years of UN-coordinated appeals – shows that FDI can be volatile and inflows can fall rapidly in the face of a crisis.

- FDI falls on average by 47% in the first year of a crisis. The proportional fall for lower middle income countries is higher than that for LICs in the first year. These countries, however, recover faster over subsequent years, a trend largely driven by countries where crisis is localised.

- Resource-rich countries among the group can be hit particularly hard, with FDI flows falling on average by 59% in the first year of crisis and volumes still a third lower than those in the year before appeal after five years.

- The proportion of FDI as a share of GDP in poor countries is significantly curtailed by crisis. For LICs currently with more than five consecutive years of humanitarian appeals, FDI accounts for 2.1% of GDP in 2017, roughly half the level of other LICs (4.1%).

- Similarly, FDI accounts for a smaller proportion of international flows in countries with two or more consecutive years of appeals in 2017 compared with other developing countries, accounting for 12% of inflows in aggregate in 2017 compared with 21% for other developing countries.

The impact of protracted crisis on the domestic private sector is also significant.

- As a share of GDP in 2017, the size of the domestic private sector in the 12 countries currently with more than five consecutive years of humanitarian appeals (estimated in terms of private sector credit) is less than a third that of other developing countries (16% and 50% respectively).

Figure 3.7: Compared with other developing countries, private finance mobilised through blended finance has remained low in countries characterised by protracted crisis

Private finance mobilised by official development finance, 2012–2017

Private finance mobilised by official development finance, 2012–2017

Source: OECD DAC.

Notes: Data for 27 protracted crisis response countries – these had at least 5 consecutive years of humanitarian response plans between 2000 and 2017 (with 2017 being the latest year for which country-level development finance data is available). Of these, 20 also had a humanitarian country response plan in the same time period. Data is in constant 2017 prices.

Blended finance is growing but remains small, with only a fraction going to poorer or fragile contexts. Amounts of blended finance mobilised per investment are also significantly smaller in poor countries than in others. [6]

- Of the US$38.2 billion of private capital mobilised by concessional finance in 2017 (the latest year for which data is available), less than 1% (0.9%) went to the 12 countries currently with more than five consecutive years of humanitarian appeals. This compares with the 12% of total ODA they receive.

- Investments are also highly concentrated. Just four lower middle income countries (Angola, Côte d’Ivoire, Indonesia and Kenya) account for over two thirds (67%) of capital mobilised to protracted crisis response countries since 2012.

Blended finance is only one of the ways the public sector can work with private capital. Governments and ODA can also work to strengthen the enabling environment for private sector development – including through policy and institutional reforms and market functioning activities that can address market failures and improve production, distribution and integration of actors into markets. [7] With a strong enabling environment both domestic and international private actors can flourish and become more resilient to shocks and crises. Aid investments supporting such measures, however, are low.

- Evidence in fact suggests that increasing international private inflows to LICs does not strengthen the domestic private sector – if anything the correlation is weakly negative. [8]

- Stronger public spending for the enabling environment may, therefore, have greater systemic and transformational impacts on the growth and resilience of the economy, especially in the poorest countries and those in fragile situations, compared with project- or deal-level investments which characterise blended finance initiatives. [9]

- However, aid investments supporting broader private sector development are low and particularly low in protracted crisis response countries. They accounted for 6.3% of all ODA in 2017, only 15% of which was allocated to protracted crisis response countries (compared with a fifth of total aid). In these countries just 4.6% of aid is directed to such investments. For countries currently with appeals for more than five consecutive years the proportion is even lower, at 3.8%.

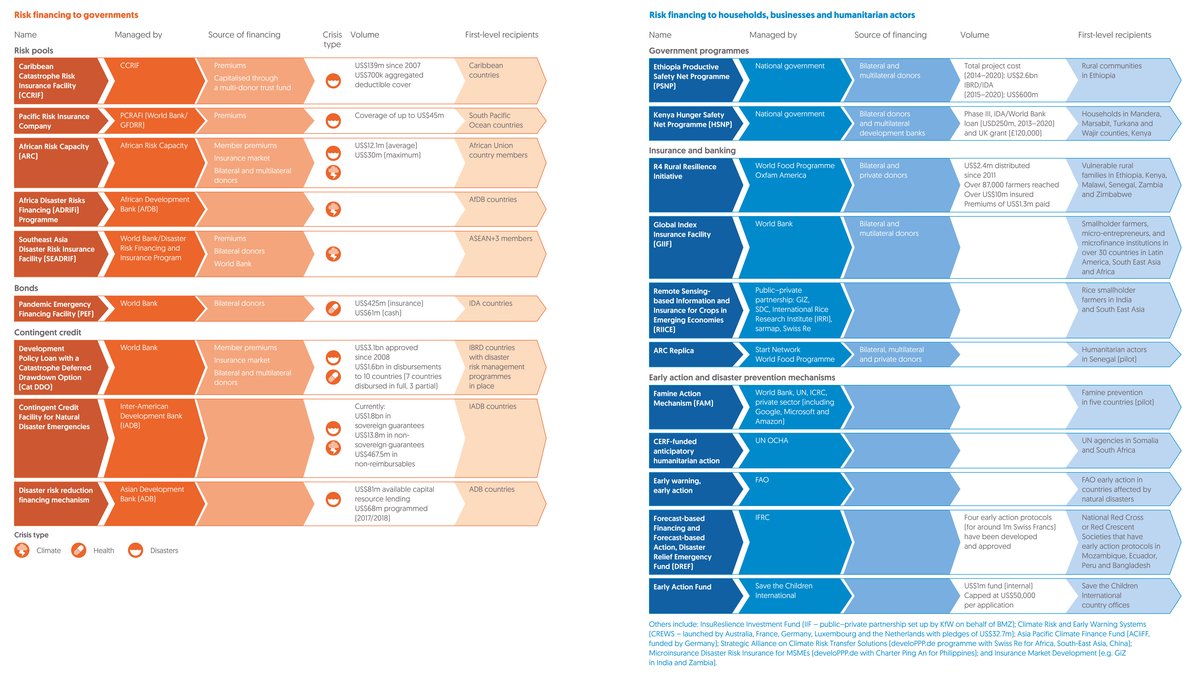

Risk financing

While crisis can impact the ability of the private sector to operate freely and effectively, the sector also has the potential to play a role in managing crises. There is increasing interest in the potential of risk financing and the role of the banking and insurance sectors to support this. This financing allows governments, organisations and individuals to financially prepare, and often act, in advance of a crisis based on an informed idea of future events (usually agreed upfront and based on a parametric trigger, index or threshold) rather than responding to manifest or emerging ‘needs’ once they are already established. [10]

There are a range of different mechanisms and tools in place which provide a foundation for the further expansion of risk financing. For this to be effective, good information and data, along with accurate interpretation, are needed to inform decision-making and to assess impact. And a layered financing strategy is needed across different actors and sources of finance, relying not just on insurance but also, for instance, on having disaster risk reduction budgets and emergency reserves in place. [11]

Most mechanisms and products currently focus on risks associated with disasters and are designed to enable planning to protect investments, meet the cost of disasters before they happen and increase the speed, predictability and transparency of disaster response. [12] Though not a comprehensive mapping, Figure 3.8 provides an overview of some of these mechanisms and instruments, including, where available, data on volumes of funding. In addition to the tools and products developed for governments by multilateral development banks, and banking insurance products, the figure includes several recent anticipatory or early action financing initiatives, which are similarly based on the idea of acting or financing with an informed idea of risk rather than manifest need. [13] [14]

Some estimates suggest insurance could provide financing for 20% or 30% of identified humanitarian needs. [15] However, disaster risk financing is about more than just insurance.

- There are also mechanisms that provide incentives for governments to develop and improve policies on disaster risk management, such as the Development Policy Loan with a Catastrophe Deferred Drawdown Option (Cat DDO). [16]

Most risk financing has, to date, focused on disasters with hazard triggers.

- There has been limited risk financing for fragility, conflict and violence, or refugee crises. However, actors are beginning to focus attention on these issues. For instance, the World Bank has established the Global Crisis Risk Platform to improve its crisis-related financing tools, with a particular focus on prevention and compound risks (macro shocks, disasters, conflict, food emergencies and pandemics). [17] [18]

Donors are increasingly deploying grant resources to support effective and innovative risk financing solutions. [19]

- Grant-like funding is being provided to advisory bodies working to stimulate the development of insurance markets and appropriate risk products, or to provide technical and advisory services, like the Disaster Risk Financing and Insurance Program’s Global Partnership for Climate and Disaster Risk Finance and Insurance Solutions, InsuResilience. [20]

Figure 3.8: There is considerable potential for risk financing to play a greater role, but better data and information is needed to inform decision-making

Examples of risk financing instruments

Examples of risk financing instruments

Source: Development Initiatives based on information collected from the websites of the respective risk financing instruments, or of the institutions behind them, and based on information provided bilaterally from representatives of those instruments.

Notes: CERF: UN Central Emergency Response Fund; FAO, Food and Agriculture Organization; GDFRR: Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery; IBRD, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; ICRC, International Committee of the Red Cross; IDA: International Development Association; SDC: Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation. BMZ is the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development and KfW is the German Development Bank. Information in the tables reflects what could be gathered from sources as of 31 July 2019.

ODA for disaster risk reduction

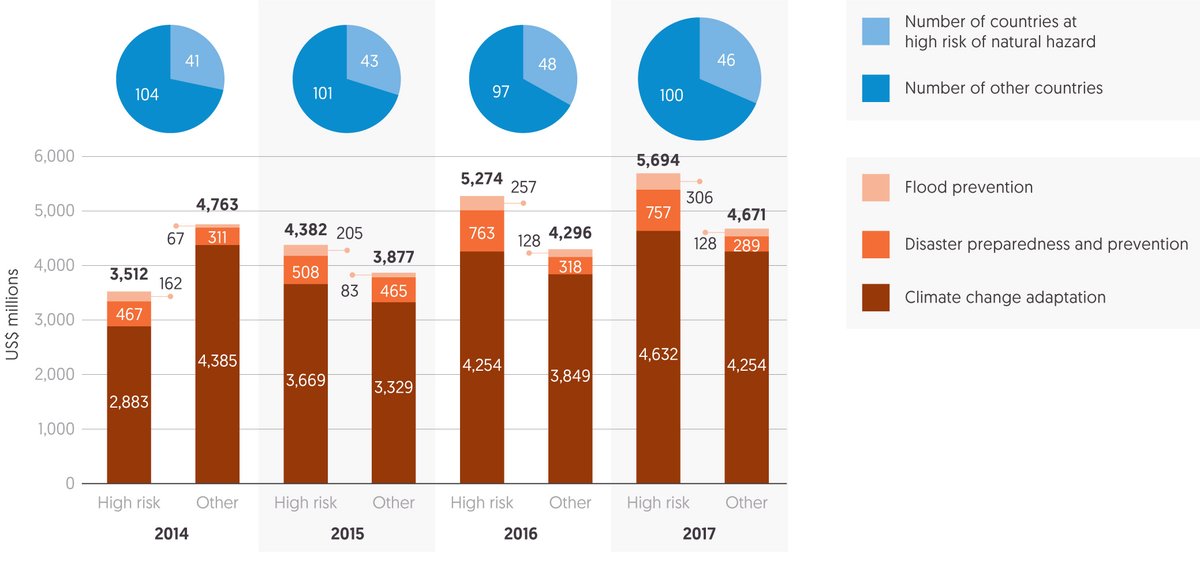

Figure 3.9: International funding related to disaster risk reduction increasingly targets high-risk countries

ODA relevant to disaster risk reduction by countries’ risk of natural hazards, 2014–2017

ODA relevant to disaster risk reduction by countries’ risk of natural hazards, 2014–2017

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD DAC data and INFORM Index for Risk Management.

Notes: High-risk countries are those with an INFORM Risk Index of at least 4.7 natural hazards each year between 2014 and 2017. Analysis includes funding from all recipient countries. The Rio markers for climate change adaptation were not introduced until 2010, hence the significant increase from this year onwards for the last category. Data is in constant 2017 prices.

In 2018, 18 of the 40 countries with the largest populations in need experienced disasters caused by natural hazards (see Chapter 1, Figure 1.2). Increasing attention is focused on the need to prevent and prepare for predictable natural hazards. This includes a greater role for the private sector through risk insurance (see Figure 3.9). International assistance, both humanitarian and development, is also being channelled to reduce the risk of disasters and mitigate their impact. The volume and proportion of total assistance related to disaster risk reduction (DRR) directed to high-risk countries has increased steadily.

- Total funding related to DRR has increased from US$8.3 billion in 2014 to US$10.4 billion in 2017, a 25% rise.

- In 2014, 41 countries were classified as at high risk of disasters and received a total of US$3.5 billion in funding related to DRR. This accounted for 42% of total DRR funding.

- By 2017, the number of countries classified as at high risk had increased to 46, with their funding totalling US$5.7 billion (a rise of US$2.2 billion from 2014, or 62%). This funding to high-risk countries also made up a higher proportion of total funding related to DRR, increasing to 55%.

Historical data on funding directly targeted to DRR is not easily identifiable on public databases, beyond the related purpose codes and marker shown in Figure 3.9, which capture a wide range of financing potentially contributing to DRR. However, the DAC has introduced a new marker on DRR as well as a designated purpose code. [21] The marker will be able to be applied across sectors to demonstrate the explicit risk reduction intent of the project investment, allowing for better tracking of where funding for DRR is directed.

Downloads

Notes

-

1

OECD DAC, 2019. DAC Recommendation on the OECD Legal Instruments Humanitarian-Development Peace Nexus. Available at: https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/public/doc/643/643.en.pdfReturn to source text

-

2

This excludes Sudan, which also experienced a combined decrease in developmental ODA and humanitarian assistance in its fifth year of crisis compared with the year before appeal. However, data in the year before appeal includes assistance to South Sudan, but in the fifth year of crisis excludes it, as that is after the independence of South Sudan.Return to source text

-

3

‘Grant element’ is the standard way of measuring how concessional a loan is. It can be viewed as the difference between the cost, in today’s prices, of the future repayments a borrower will have to make on the loan in question and the repayments the borrower would have had to make on a non-concessional loan. This is therefore the amount of money that is considered to have been given away by the donor. The grant element is normally shown as a percentage of the value of the loan.Return to source text

-

4

See, for example, OECD/UN Capital Development Fund, 2019. Blended Finance in the Least Developed Countries 2019. OECD Publishing, Paris. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1787/1c142aae-enReturn to source text

-

5

All analysis in this section excludes China, whose large volumes of FDI and private sector credit skew developing country trends.Return to source text