Read our new report on humanitarian funding and reform

Our report 'Falling short? Humanitarian funding and reform' presents the latest data on global humanitarian assistance, as well as progress on Grand Bargain localisation targets, cash and voucher assistance, and anticipatory action.

Read the reportSummary

In 2021, the number of people in need of humanitarian assistance continued to increase. An estimated 306.0 million people were assessed to be in need, 90.0 million more than in 2019 before the Covid-19 pandemic. Half of those requiring humanitarian support (155.9 million) lived in just nine countries. Long-term crisis is increasingly normal. The number of countries experiencing protracted crisis rose to 36 in 2021, accounting for three quarters (74%) of all people in need.

Covid-19 overlaid other pre-existing and emerging crisis risks, driving need and complicating response. Those experiencing humanitarian crisis have been left behind in efforts to recover from the pandemic, with people experiencing long-term crisis furthest behind. The average Covid-19 vaccination rate is 26% for countries experiencing protracted crisis, compared to 64% for countries without a UN-coordinated humanitarian appeal.

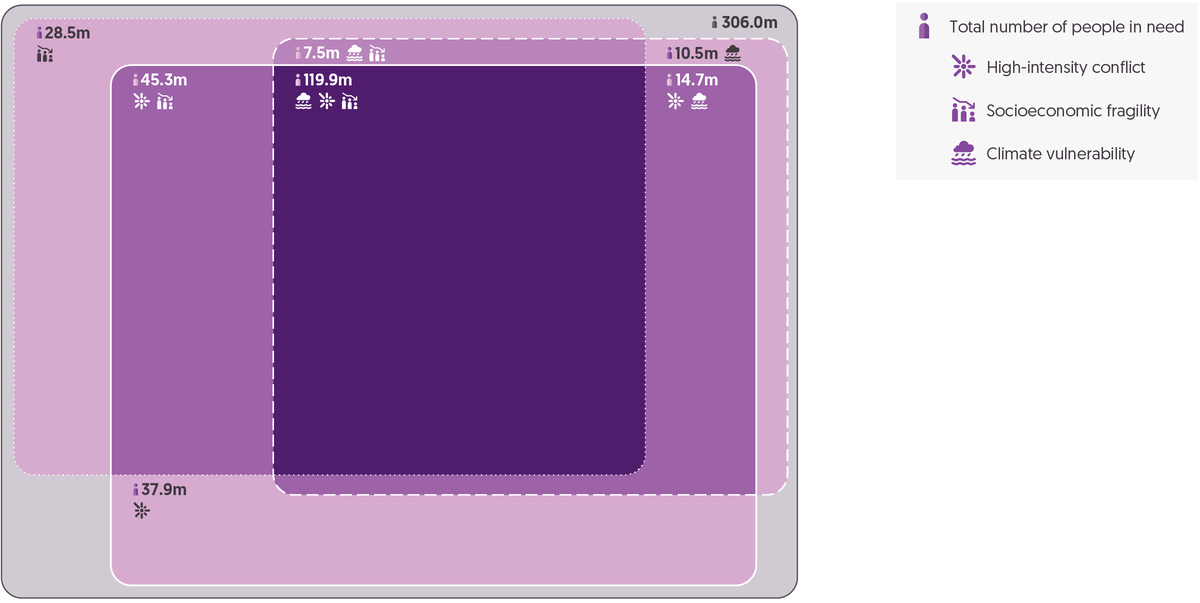

Climate change acts as both driver and multiplier of crisis risks, with those already in need of humanitarian assistance particularly vulnerable. In 2021, half of all people in need (50%, 152.6 million people) lived in countries with high levels of vulnerability to the impacts of climate change. Multiple drivers of crisis intersect, compounding the risk of and exposure to crisis. Two fifths of people in need in 2021 (39%, 119.9 million people) lived in countries facing a combination of high-intensity conflict, high levels of socioeconomic fragility and high levels of vulnerability to the impacts of climate change. The intersection of climate risk with the other two factors is particularly important, as high levels of fragility and conflict limit access to climate resources. High-intensity conflict can increase climate risk, in turn creating more fragility and increasing the risk of further conflict. Almost three quarters (217.7 million, 71%) of people in need of humanitarian assistance live in countries experiencing high-intensity conflict.

Even before the Ukraine crisis, mounting food insecurity has been a notable challenge. In 2020/21, the number of people experiencing food insecurity (crisis, food emergency or famine) grew rapidly, rising to 160.4 million, a third more than in 2019/20. Of all people facing food insecurity, half (52%, 82.9 million people) were in just four countries. Rising food prices in 2022, driven by the conflict in Ukraine, are now posing further threats to food security.

The number of displaced people continued to rise in 2021, increasing to 86.3 million people, 4.7% higher than in 2020. The consolidated picture from 2021 already looks markedly different as the outbreak of war in Ukraine has displaced many millions more. Since February 2022, an estimated 12.8 million people have fled the violence, to neighbouring countries or internally.

Figure 1.1: Many more people, in more countries, continue to be affected by humanitarian crises than in 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic

People in need, type and severity of crisis, and funding requirements, 2021

| - | - | - | Crisis info | Crisis info | Crisis info | Risk dimensions | Risk dimensions |

Crisis type

markers |

Crisis type markers | Crisis type markers |

Financial

data |

Financial data | Financial data | Financial data | Financial data | Financial data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Country

ID |

Country | People in need (millions) | Severity score | Protracted/ Recurrent crisis | Years of consecutive crisis | Covid-19 vaccination rate |

Climate

vulnerability |

Conflict marker |

Displacement

marker |

Physical disaster marker |

Country response plan

requirements (US$ millions) |

Country

response plan funding (US$ millions) |

Coverage (%) |

Regional response plan

requirements (US$, million) |

Regional

response plan funding (US$ millions) |

Coverage

(%) |

| YEM | Yemen | 24.2 | 5 | Protracted | 14 | 2% | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3,853 | 2,425 | 63% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| ETH | Ethiopia | 23.9 | 5 | Protracted | 8 | 21% | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2,445 | 1,377 | 56% | 304 | 53 | 17% |

| COD | DRC | 19.6 | 4 | Protracted | 22 | 1% | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1,984 | 876 | 44% | 71 | 20 | 28% |

| AFG | Afghanistan | 18.4 | 4 | Protracted | 14 | 13% | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1,475 | 2,075 | 141% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| NGA | Nigeria | 16.4 | 4 | Protracted | 8 | 11% | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1,006 | 725 | 72% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| VEN | Venezuela | 14.8 | 3 | Recurrent | 4 | 77% | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 708 | 279 | 39% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| SDN | Sudan | 14.3 | 5 | Protracted | 22 | 13% | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1,940 | 732 | 38% | 306 | 64 | 21% |

| SYR | Syria | 13.4 | 5 | Protracted | 10 | 13% | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4,224 | 2,119 | 50% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| PAK | Pakistan | 11.0 | 2 | Protracted | 6 | 60% | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 332 | 342 | 103% | 133 | 52 | 39% |

| PRK | DPR Korea | 10.4 | 4 | - | - | n/d | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | |

| COL | Colombia | 8.5 | 4 | Recurrent | 4 | 82% | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 174 | 84 | 48% | 641 | 328 | 51% |

| SSD | South Sudan | 8.3 | 4 | Protracted | 11 | 5% | n/d | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1,678 | 1,156 | 69% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| SOM | Somalia | 7.7 | 4 | Protracted | 22 | 12% | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1,092 | 850 | 78% | 30 | - | 0% |

| ZWE | Zimbabwe | 7.0 | 4 | Recurrent | 3 | 39% | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 507 | 96 | 19% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| TCD | Chad | 6.4 | 5 | Protracted | 18 | 13% | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 618 | 214 | 35% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| MLI | Mali | 5.9 | 4 | Protracted | 18 | 7% | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 563 | 217 | 39% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| HTI | Haiti | 5.1 | 5 | Protracted | 12 | 2% | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 423 | 145 | 34% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| NPL | Nepal | 4.9 | n/a | - | 1 | 75% | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 84 | 7 | 9% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| CMR | Cameroon | 4.4 | 4 | Protracted | 8 | 6% | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 362 | 196 | 54% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| IRQ | Iraq | 4.4 | 5 | Protracted | 10 | 25% | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 607 | 393 | 65% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| MOZ | Mozambique | 4.1 | 4 | Recurrent | 3 | 45% | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 254 | 223 | 88% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| NER | The Niger | 3.8 | 3 | Protracted | 17 | 9% | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 523 | 269 | 51% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| PSE | Palestine | 3.8 | 5 | Protracted | 19 | 38% | n/d | 1 | 0 | 0 | 513 | 436 | 85% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| GTM | Guatemala | 3.8 | 3 | - | 1 | 44% | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 56 | 35 | 62% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| MMR | Myanmar | 3.7 | 4 | Protracted | 9 | 54% | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 386 | 256 | 66% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| BFA | Burkina Faso | 3.5 | 5 | Protracted | 18 | 10% | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 608 | 299 | 49% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| KEN | Kenya | 3.4 | 3 | Protracted | 14 | 22% | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 139 | 27 | 19% | 110 | 23 | 21% |

| IRN | Iran | 3.4 | 4 | - | - | 76% | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | n/d | n/d | n/d | 136 | 34 | 25% |

| UKR | Ukraine | 3.4 | 4 | Protracted | 8 | 36% | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 168 | 108 | 65% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| HND | Honduras | 3.3 | 4 | - | 1 | 52% | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 156 | 104 | 66% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| LBN | Lebanon | 3.2 | 4 | Protracted | 10 | 37% | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 168 | 124 | 74% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| CAF | Central African Republic | 2.8 | 4 | Protracted | 19 | 19% | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 445 | 401 | 90% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| MWI | Malawi | 2.6 | 3 | - | - | 8% | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| ERI | Eritrea | 2.6 | 3 | - | - | n/d | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| PHL | The Philippines | 2.5 | 3 | - | - | 63% | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| TUR | Turkey | 2.4 | 3 | Protracted | 10 | 68% | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| BDI | Burundi | 2.4 | 4 | Protracted | 6 | 0% | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 195 | 88 | 45% | 51 | 19 | 37% |

| SLV | El Salvador | 1.7 | 3 | - | 1 | 70% | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 42 | 22 | 53% | n/d | n/d | n/d |

| ZMB | Zambia | 1.7 | 3 | Recurrent | 4 | 15% | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | n/d | n/d | n/d | 75 | 13 | 17% |

| MDG | Madagascar | 1.6 | 4 | - | 1 | 4% | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 166 | 127 | 76% | n/d | n/d | |

| UGA | Uganda | 1.5 | 3 | Protracted | 8 | 33% | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | n/d | n/d | n/d | 767 | 162 | 21% |

| JOR | Jordan | 1.5 | 4 | Protracted | 10 | 46% | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d |

Source: Development Initiatives based on UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Humanitarian Programme Cycle (HPC), ACAPS, Our World In Data, UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), INFORM Index for Risk Management, Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research (HIIK), Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN), Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) and UN OCHA Financial Tracking Service (FTS) data.

Notes: Countries are selected using UN OCHA and ACAPS estimates of people in need. Countries with fewer than an estimated 1.5 million people in need are not shown.

People affected by crisis

In 2021, the numbers of people in need of humanitarian assistance continued to rise rapidly. The far-reaching impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic and increasing threat of climate-driven crises, as well as new and worsening conflicts, are driving a significant growth in the number of countries affected by crisis, the number of countries with high levels of humanitarian need, and the total number of people needing humanitarian assistance.

- In 2021, an estimated 306.0 million people living in 73 countries were assessed to be in need of humanitarian assistance, 90.4 million more than in 2019 before the Covid-19 pandemic. Comparison with 2020 is complicated by the year's upsurge in needs related to Covid-19, and the separation of these needs from other non-Covid-19 related ones is a distinction only made in the data for 2020. Excluding needs related to Covid-19 there were an estimated 243.8 million people in need living in 75 countries in 2020.

- The Covid-19 pandemic drove demand for coordinated international humanitarian responses in more countries in 2020. In 2021, the demand remained high. There were 48 UN-coordinated appeals, 7 fewer than in 2020 but a third more than the 36 appeals in 2019, before the impact of Covid-19 ( see Figure 2.2, Chapter 2 ).

- In 2021, the number of countries with high levels of humanitarian need (identified as having more than one million people in need) increased to 49, from 40 countries in 2020, with the Covid-19 pandemic continuing to compound other political, socioeconomic and climate-related drivers of crisis.

High numbers of people in need continue to be concentrated in a small number of countries.

- More than half (155.9 million) of the total number of people in need in 2021 lived in just nine countries.

- Ten countries had more than 10 million people in need in 2021: Yemen (24.2 million), Ethiopia (23.9 million), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (19.6 million), Afghanistan (18.4 million), Nigeria (16.4 million), Venezuela (14.8 million), Sudan (14.3 million), Syria (13.4 million), Pakistan (11.0 million) and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (10.4 million). Of these, six countries have consistently had more than 10 million people in need since 2019 (Yemen, Syria, DRC, Afghanistan, Venezuela and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea).

- In 2021, there was a significant jump in people requiring humanitarian assistance in Ethiopia (increase of 15 million), Pakistan (increase of 8.0 million), Nigeria (increase of 7.0 million) and Afghanistan (increase of 4.4 million).

In many countries, people are experiencing a number of intersecting vulnerabilities, as the ongoing impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic compound conflict- and climate-driven crisis. In particular, the impacts of climate change are increasingly acting as a catalyst for crisis, especially in those states with the lowest levels of resilience (see ‘ Humanitarian need and intersecting dimensions of risk ’; ‘ Climate finance flows’, Chapter 2 ; and ‘ Development financing for disaster risk reduction’, Chapter 3 ). As these shocks compound existing crises, protracted crises have become more prevalent than ever.

- In 2021, the number of countries experiencing protracted crisis (countries with five or more consecutive years of UN-coordinated appeals) increased to 36, from 34 countries in 2020. A further 20 countries were experiencing recurrent crisis, with appeals in more than one consecutive prior year.

- Most people in need of humanitarian assistance live in countries experiencing protracted crisis: the 36 countries experiencing protracted crisis in 2021 accounted for 74% (227.3 million) of total people in need.

- Of the 36 countries experiencing protracted crisis, 25 were classified as having high or very high climate vulnerability.

The sustained impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic include economic disruption, school closure and increased health needs. These overlap with and compound existing needs in countries experiencing crisis. This disparity is illustrated by accessibility of vaccinations.

- Countries experiencing protracted crisis have lower Covid-19 vaccination rates: an average of 26% in countries experiencing protracted crisis, compared to 53% in other countries with a humanitarian appeal, and 64% in countries without a humanitarian appeal.

Humanitarian need and intersecting dimensions of risk

Figure 1.2: People in need increasingly face intersecting risks of climate vulnerability, socioeconomic fragility and conflict

Dimensions of risks and vulnerabilities facing people in need

|

Climate

vulnerability |

Socioeconomic fragility | Conflict intensity | People in need (millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | High | High | 119.9 |

| High | Low | High | 14.7 |

| High | High | Low | 7.5 |

| High | Low | Low | 10.5 |

| Low | High | High | 45.3 |

| Low | High | Low | 28.5 |

| Low | Low | High | 37.9 |

| Low | Low | Low | 41.7 |

Source: Development Initiatives based on UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Humanitarian Programme Cycle (HPC), ACAPS, Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) States of Fragility (SoF) and Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research (HIIK).

Notes: Numbers of people in need are aggregated by country-level risk, vulnerability and fragility. Conflict risk is based on the presence of high conflict intensity (HIIK); high socioeconomic fragility is based on the top 20% of average social, economic and political fragility score (OECD); high climate risk is based on the top 20% of ND-GAIN score (ND-GAIN). Country dimensions missing data are classified as low vulnerability/hazard.

Systemic shocks like the Covid-19 pandemic and climate change are compounding other risk factors for crises, both sudden and slow-onset, with more countries experiencing protracted, long-term humanitarian need (see ‘ People affected by crisis ’). Where resilience is low, the likelihood of people experiencing crisis and needing more lifesaving humanitarian assistance, and for longer, is greater. Conflict, socioeconomic fragility and vulnerability to climate change, in isolation or combination, can serve as both drivers and multipliers of a crisis: worsening impacts, lowering resilience and frustrating efforts to provide the longer-term support needed for recovery from crisis. Understanding where people in need are exposed to specific and intersecting risks can help to identify where the likely impacts of shocks may be greatest, and where we need more and better joined-up humanitarian, development, peacebuilding and climate interventions.

Many countries continued to experience complex crises in 2021.

- Among the 73 countries with people in need in 2021, half (37) experienced more than one type of humanitarian crisis, including natural hazards and conflict-related or displacement crises. 16 countries experienced all three types, similar to the previous year.

- Overall, 43 countries experienced disasters associated with natural or technical hazards – with half of all people in need (50%, 152.6million people) living in countries facing high levels of vulnerability to the impacts of climate change – 30 experienced conflict and 47 experienced displacement.

- The severity of existing crises also worsened in 2021: the number of countries with crises classified as ‘very high’ severity doubled to 10, from 5 in 2020. A further 10 countries increased in severity level.

In 2021, most people in need of humanitarian assistance were experiencing at least one of the following three intersecting dimensions: high-intensity conflict, high levels of socioeconomic fragility and high levels of vulnerability to the impacts of climate change.

- 61% of people in humanitarian need (187.4 million people) were living in countries with at least two of the three dimensions.

- Two fifths of people in need (39%, 119.9 million people) were living in countries facing a combination of all three dimensions.

The need for a joined-up approach, addressing immediate humanitarian need as well as building resilience to socioeconomic and climate shocks and addressing underlying developmental and peacebuilding needs in crisis settings, is widely acknowledged. [1] (See also ‘ Climate finance flows', Chapter 2 ; and ‘ Multilateral development bank financing to countries experiencing crisis ’, ‘ World Bank financing in crisis contexts ’ and ‘ Development financing for disaster risk reduction ’, all Chapter 3). However, as the growth in the number of protracted crises illustrates, this has rarely been achieved.

The intersection of conflict and climate vulnerability can be particularly problematic. High-intensity conflict creates operational risks for development projects aimed at decreasing climate vulnerability, which can result in projects being relocated or, in unstable areas, not being accessed at all. [2] Where this happens, a greater reliance on humanitarian rather than development interventions can occur, further exacerbating longer-term vulnerability. It also results in more funding being channelled through multilateral organisations, with less flexibility in quickly evolving situations and decreased local participation. [3]

Addressing conflict is critical to preserve life, reduce humanitarian need and enable sustainable development. But it is also important as a means to reduce climate risk. In 2021, almost three quarters (217.7 million, 71%) of people in need were living in countries currently experiencing high-intensity conflict. In these contexts, people are less likely to receive resources related to climate adaptation, but conflict itself can also pose an increased climate risk. International law forbids specific threats to the natural environment but, from 1946 to 2010, conflict was the single most important predictor of declines in certain wildlife populations. This affects ecosystems’ ability to mitigate the worst effects of climate change, limiting the contribution they can make to reducing rises in global warming. [4] Degraded environments also make it more difficult for communities to adapt to the risks presented by climate change. [5]

Figure 1.3: Global levels of food insecurity are rising and concentrated in just a few countries

Food insecurity – 10 largest populations reported 2019/20–2020/21

| Country | Rank | High intensity conflict marker | 2019/20 | 2019/20 | 2019/20 | 2020/21 | 2020/21 | 2020/21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crisis+ | Emergency+ | Famine | Crisis+ | Emergency+ | Famine | |||

| DRC | 1 | 1 | 19.6 | 4.9 | - | 25.9 | 5.4 | - |

| Afghanistan | 2 | 1 | 13.2 | 4.3 | - | 22.8 | 8.7 | - |

| Nigeria | 3 | 1 | 13.0 | 1.2 | - | 18.0 | 0.6 | 0.0 |

| Yemen | 4 | 1 | 16.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 16.2 | 5.1 | 0.0 |

| Ethiopia | 5 | 1 | 4.0 | 0.9 | - | 7.8 | 2.8 | 0.4 |

| South Sudan | 6 | 1 | 5.5 | 1.2 | - | 7.3 | 2.5 | 0.1 |

| Sudan | 7 | 1 | 7.1 | 1.3 | - | 6.0 | 1.3 | - |

| Pakistan | 8 | - | 1.2 | 0.4 | - | 4.7 | 1.0 | - |

| Haiti | 9 | - | 4.4 | 1.2 | - | 4.6 | 1.3 | - |

| Niger | 10 | - | 1.7 | 0.1 | - | 3.6 | 0.3 | - |

Source: Development Initiatives based on Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), and Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research (HIIK).

Notes: Acute food insecurity numbers and phases are as reported/projected by the year's closest IPC survey. People living in 'Crisis' (phase 3) or with higher food insecurity are shown. Because IPC survey coverage varies between years, only surveys that mapped ±25% of the 2020/2021 survey population share were used for comparison. 2019/2020 data for Yemen is based on the 2018 survey. Bubble scaling is not precise.

Food insecurity has become an increasingly important driver of humanitarian need and is likely to be even more significant as the conflict in Ukraine, supply-chain issues and a severe drought in the Horn of Africa drive up food prices. As with other dimensions of risk, there is an overlap between food insecurity and areas experiencing high-intensity conflict.

- Between 2019/20 and 2020/21, the number of people experiencing crisis or higher levels of food insecurity (food emergency and famine) increased by over a quarter (28%, from 124.9 million to 160.4 million people). [6]

- Of these 160.4 million people, 33.9 million (22%) were experiencing emergency-level food insecurity, and 0.6 million people (0.4%) in four countries (Ethiopia, Nigeria, Yemen and South Sudan) were experiencing famine.

- A small number of countries accounted for a large proportion of those facing food insecurity. Just four countries were home to half (52%, 82.9 million people) of all people facing crisis or higher levels of food insecurity: DRC (25.9 million), Afghanistan (22.8 million), Nigeria (18.0 million) and Yemen (16.2 million).

- There is a notable overlap between people experiencing high levels of food insecurity and people living with conflict. Of the 10 countries with the highest levels of food insecurity, the top 7 were all also experiencing high-intensity conflict in 2021.

- In 2020/21, the severity of food insecurity [7] increased for five of the largest populations experiencing food insecurity. Ethiopia, South Sudan and Afghanistan experienced the largest increases in the severity of food insecurity. Along with Yemen, South Sudan and Afghanistan also experienced the highest levels of severity in 2019/20.

Forced displacement

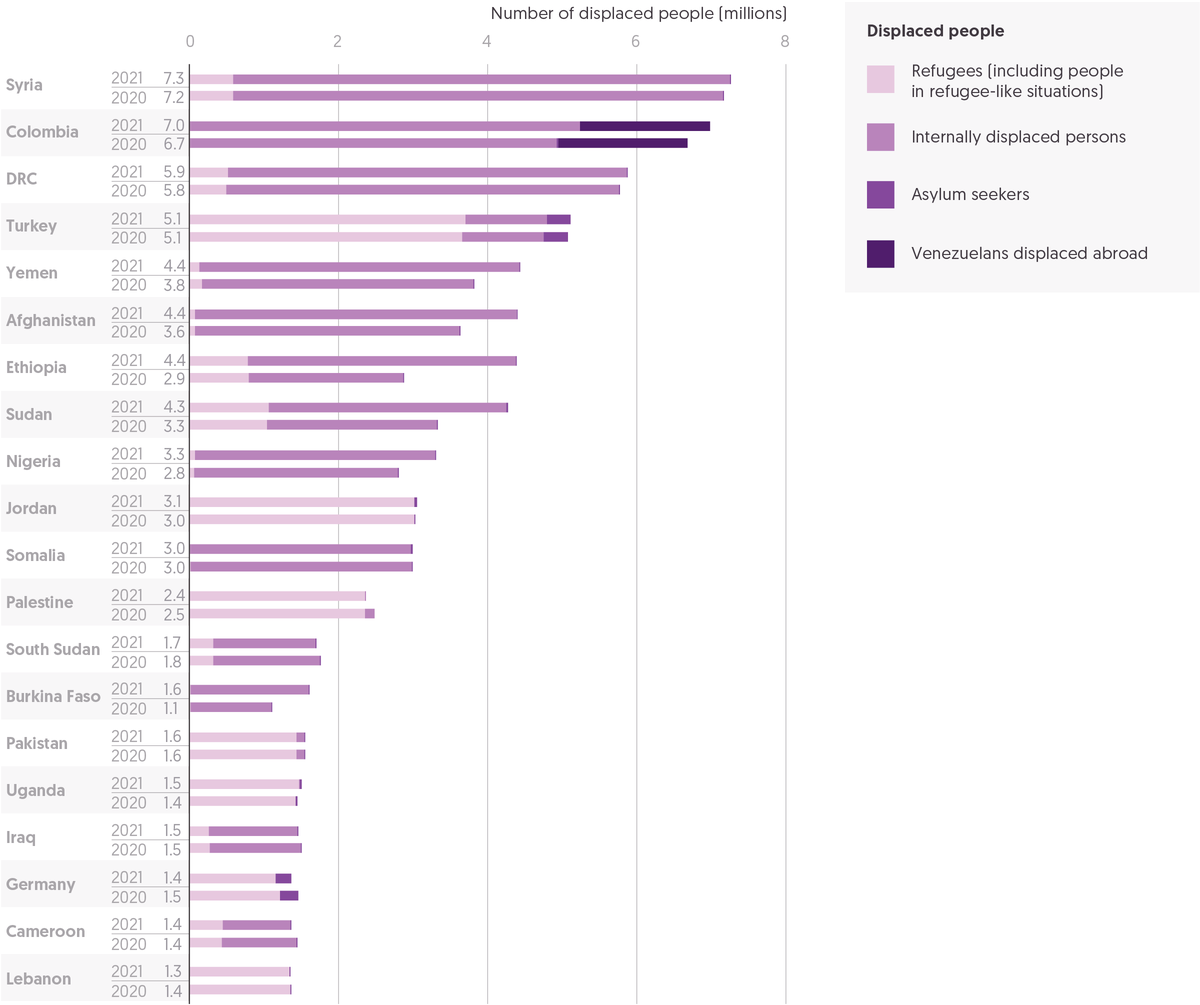

Figure 1.4: The number of people forcibly displaced grew for the tenth consecutive year in 2021

20 countries with the largest forcibly displaced populations, 2020−2021

| Rank | ISO | Country | Year |

Refugees (including people in

refugee-like situations) |

Internally displaced

persons |

Asylum seekers | Venezuelans displaced abroad | Total displaced population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SYR |

Syrian Arab

Republic |

2020 | 0.6 | 6.6 | 0.0 | - | 7.2 |

| 2021 | 0.6 | 6.7 | 0.0 | - | 7.3 | - | - | - |

| 2 | COL | Colombia | 2020 | 0.0 | 4.9 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 6.7 |

| 2021 | 0.0 | 5.2 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 7.0 | - | - | - |

| 3 | COD | Congo, Dem. Rep. | 2020 | 0.5 | 5.3 | 0.0 | - | 5.8 |

| 2021 | 0.5 | 5.3 | 0.0 | - | 5.9 | - | - | - |

| 4 | TUR | Turkey | 2020 | 3.7 | 1.1 | 0.3 | - | 5.1 |

| 2021 | 3.7 | 1.1 | 0.3 | - | 5.1 | - | - | - |

| 5 | YEM | Yemen | 2020 | 0.2 | 3.6 | 0.0 | - | 3.8 |

| 2021 | 0.1 | 4.3 | 0.0 | - | 4.4 | - | - | - |

| 6 | AFG | Afghanistan | 2020 | 0.1 | 3.5 | 0.0 | - | 3.6 |

| 2021 | 0.1 | 4.3 | 0.0 | - | 4.4 | - | - | - |

| 7 | ETH | Ethiopia | 2020 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 0.0 | - | 2.9 |

| 2021 | 0.8 | 3.6 | 0.0 | - | 4.4 | - | - | - |

| 8 | SDN | Sudan | 2020 | 1.0 | 2.3 | 0.0 | - | 3.3 |

| 2021 | 1.1 | 3.2 | 0.0 | - | 4.3 | - | - | - |

| 9 | NGA | Nigeria | 2020 | 0.1 | 2.7 | 0.0 | - | 2.8 |

| 2021 | 0.1 | 3.2 | 0.0 | - | 3.3 | - | - | - |

| 10 | JOR | Jordan | 2020 | 3.0 | - | 0.0 | - | 3.0 |

| 2021 | 3.0 | - | 0.0 | - | 3.1 | - | - | - |

| 11 | SOM | Somalia | 2020 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 0.0 | - | 3.0 |

| 2021 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 0.0 | - | 3.0 | - | - | - |

| 12 | PSE | Palestine | 2020 | 2.3 | 0.1 | - | - | 2.5 |

| 2021 | 2.3 | 0.0 | - | - | 2.4 | - | - | - |

| 13 | SSD | South Sudan | 2020 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.0 | - | 1.8 |

| 2021 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.0 | - | 1.7 | - | - | - |

| 14 | BFA | Burkina Faso | 2020 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.0 | - | 1.1 |

| 2021 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 0.0 | - | 1.6 | - | - | - |

| 15 | PAK | Pakistan | 2020 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | - | 1.6 |

| 2021 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | - | 1.6 | - | - | - |

| 16 | UGA | Uganda | 2020 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | 1.4 |

| 2021 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | 1.5 | - | - | - |

| 17 | IRQ | Iraq | 2020 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.0 | - | 1.5 |

| 2021 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.0 | - | 1.5 | - | - | - |

| 18 | DEU | Germany | 2020 | 1.2 | - | 0.2 | - | 1.5 |

| 2021 | 1.2 | - | 0.2 | - | 1.4 | - | - | - |

| 19 | CMR | Cameroon | 2020 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.0 | - | 1.4 |

| 2021 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.0 | - | 1.4 | - | - | - |

| 20 | LBN | Lebanon | 2020 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | 1.4 |

| 2021 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | 1.3 | - | - | - |

Source: Development Initiatives based on data from UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) and Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC).

Notes: DRC = Democratic Republic of the Congo. The 20 countries are selected based on the size of displaced populations hosted in 2020. 'Displaced population' includes refugees and people in refugee-like situations, internally displaced persons (IDPs), asylum seekers and other displaced populations of concern to UNHCR. ‘Other displaced populations of concern to UNHCR’ includes Venezuelans displaced abroad. IDP figures refer to those forcibly displaced by conflict, and exclude those internally displaced due to climate or natural disaster. Data is organised according to UNHCR's definitions of country/territory of asylum. According to data provided by UNRWA, registered Palestine refugees are included as refugees for Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and Palestine. UNHCR data represents 2021 mid-year figures, and UNRWA data for 2021 is based on internal estimation.

The numbers of people forcibly displaced from their homes continued to grow in 2021. An escalation in conflict, including in Ethiopia, Afghanistan, Sudan and Yemen, drove a large portion of the increase, while many people continue to be displaced by economic hardship, including in Venezuela. The increase in shocks related to climate change has also driven up the numbers of people forced from their homes. [8] The consolidated picture from 2021 already looks markedly different as the outbreak of war in Ukraine has displaced many millions more. Since February 2022, an estimated 12.8 million people have fled the violence in Ukraine, both to neighbouring countries and internally. [9]

- In 2021, the total number of displaced people increased to 86.3 million, representing a 4.7% increase from 82.4 million people in 2020.

- As in recent years, most displaced people were displaced internally, within countries (62%, 53.2 million people), while just under a third were refugees (30%, 25.9 million people). In addition, there were 3.9 million Venezuelans displaced abroad (a 2.1% increase), and a slight fall in the total number of asylum seekers, from 4.1 million people in 2020 to 3.3 million in 2021.

- The increase in the number of displaced people was driven by a significant growth in the number of internally displaced persons (IDPs), an increase of 11%, or 5.1 million people.

Escalating violence and conflict in a number of contexts drove the overall increase in IDPs.

- Ethiopia saw the largest increase in forcibly displaced people, by 53%, or more than 1.5 million people, due to the ongoing war in the Tigray region. A deterioration in the security situation saw other notable increases in the number of displaced people, including in Sudan (28% increase, 0.9 million people), Afghanistan (21% increase, 0.8 million people) and Yemen (16% increase, 0.6 million people). These were nearly all driven by increases in IDPs fleeing conflict.

- Escalating violence also drove large rises in the numbers of IDPs in Burkina Faso (46% increase, 0.5 million people) and in Nigeria (18% increase, 0.5 million people).

Continuing the trend of previous years, a small number of countries continue to host the majority of forcibly displaced people. These countries face complex and intersecting risks. The Covid-19 pandemic has contributed to existing challenges of displacement, conflict and economic hardship, and displaced people are especially affected by the unequal availability of vaccines. [10]

- In 2021, 10 countries hosted over half (54%) of all displaced people globally and the 20 largest hosting countries hosted 77%. This has intensified, with all 10 largest hosting countries seeing an increase in the number of forcibly displaced people.

- The largest hosting countries are Syria, Colombia, DRC and Turkey, all hosting over 5 million displaced people each.

- The 20 largest countries hosting displaced populations had an average Covid-19 vaccination rate of 26% in 2021, markedly lower than the global goal of vaccinating 40% of people by the end of 2021.

- Two of the largest hosting countries have vaccination rates below 15%: Yemen (2%) and Syria (13%).

- Nearly half (9) of the 20 largest hosting countries are classified as low-income countries.

The largest numbers of displaced people are increasingly concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa.

- In 2021, the Sub-Saharan Africa region hosted over 32.4 million displaced people, the largest of any region in the world, accounting for 38% of the global total. This represents a significant growth since 2020 up 12%, building on similar growth (11%) in 2020. Most of these people (25.1 million) are displaced internally in the region due to conflict, and in 2021 Sub-Saharan Africa hosted 47% of the total global number of IDPs.

- The largest proportion of refugees is hosted in the Middle East and North Africa region (8.8 million people), accounting for 34% of all refugees globally. Overall numbers of displaced people in the Middle East and North Africa region remained largely similar to those in 2020.

- South Asia has seen a growing number of displaced people, with an 11% increase (0.8 million people) in 2021. This was driven by increases in people displaced both internally and regionally by the Afghanistan conflict. In total, South Asia accounted for 9.3% of the displaced population globally.

Downloads

Notes

-

1

OECD, 2019. DAC recommendation on the humanitarian–development–peace nexus. Available at: https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-5019; UNFCCC, 2017. Technical report: opportunities and options for integrating climate change adaptation with the Sustainable Development Goals and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. Available at: https://unfccc.int/documents/28265Return to source text

-

2

SPARC, 2021. Exploring the conflict blindspots in climate adaptation finance. Available at: https://www.sparc-knowledge.org/resources/synthesis-report-exploring-conflict-blind-spots-climate-adaptation-financeReturn to source text

-

3

SPARC, 2021. Exploring the conflict blindspots in climate adaptation finance. Available at: https://www.sparc-knowledge.org/resources/synthesis-report-exploring-conflict-blind-spots-climate-adaptation-finance . Research has also shown that countries with high levels of extreme poverty have received a lower proportion of climate adaptation finance. See: Development Initiatives, 2016. Climate finance and poverty: exploring the linkages between climate change and poverty evident in the provision and distribution of international public climate finance. Available at: /resources/climate-finance-and-poverty/Return to source text

-

4

ICRC, 5 June 2019. Natural environment: neglected victim of armed conflict, www.icrc.org/en/document/natural-environment-neglected-victim-armed-conflict (accessed 4 June 2022); Martinezcuello, Francesco, 11 April 2022, Ukraine is ground zero for the environmental impacts of war, www.sierraclub.org/sierra/ukraine-ground-zero-for-environmental-impacts-war#:~:text=The%20manufacture%20of%20nitric%20acid,day%20of%20the%20Ukraine%20War.u (accessed 9 June 2022)Return to source text

-

5

ODI, ICRC, March 2019. Double vulnerability: the humanitarian implications of intersecting climate and risk. Available at: https://odi.org/en/publications/double-vulnerability-the-humanitarian-implications-of-intersecting-climate-and-conflict-risk/Return to source text