How is aid changing in the Covid-19 pandemic?

This briefing sets out near real-time data on aid for the first half of 2020. It shows how commitments are changing in the Covid-19 pandemic and where these are most likely to affect the poorest people and places.

DownloadsIntroduction

The Covid-19 pandemic presents the biggest global challenge we have faced since World War 2. The poorest people and places have been hit hardest by the economic and social effects of the crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, and are also the least resilient to its effects. Measures put in place by governments to suppress the virus have also had the greatest impact on those living in poverty.

This is leading to rising needs, while resources are falling. [1] Poverty is set to increase – with our projections suggesting extreme poverty will grow by 3% in 2020 alone. At the same time, domestic revenues in developing countries are projected to drop by US$1 trillion in 2020 from pre-Covid levels, and recovery is likely to take time. Many of these countries are heavily reliant on other critical forms of international finance – such as foreign direct investment, tourism receipts and remittances – which have also fallen steeply this year.

Financing that targets the poorest and most vulnerable people and places, including international assistance in the form of aid, is vital to address the immediate consequences of the pandemic and the longer-term setbacks to progress towards meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). At the same time, donors are heading into recession, leading to significant cuts to aid budgets already being announced by key donors, such as the UK.

Aid is changing in the face of the pandemic, with short-term, and possibly long-term, effects.

In order to guide and assess effective rapid and longer-term responses, and maximise the impact of aid, we need new types of real-time information about how aid is changing now in light of Covid-19.

Detailed information about official development assistance (ODA) in 2020 will not be published by the OECD DAC – the body that publishes comprehensive, verified ODA data – until 2021. Information on 2020 commitments and spending volumes will not be published until April 2021. More detailed information on important questions, such as where ODA is being spent and how sector allocations are changing, will not be available until December 2021.

To meet the need for more timely information, this paper uses near real-time data on aid, published by donors and implementing agencies to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI). [2]

While this analysis is by necessity limited to the data that is published to a sufficient standard and in a timely enough fashion, and is not therefore a comprehensive picture of all donors, IATI data has nevertheless reached a sufficient level of quality and coverage to enable critical analysis of near real-time trends, and provide a vital early warning system on current aid spending. As we seek to better respond to the new challenges Covid-19 is causing, this is a vital tool to enable action while there is still time to respond.

Using IATI data

An important note about the data in this paper

In this paper, we use the term ‘aid’ as per its use in IATI data. In this context, aid incorporates all humanitarian and development assistance, including ODA (as defined by the OECD DAC ), other official flows (OOFs) and any other development flows reported by official actors to IATI.

- This report does not cover all aid but rather looks at a range of key donors – bilateral donors, international financial institutions (IFIs) and multilateral institutions – which together comprise about 70% of all aid. This gives us a strong indication of what is happening to aid in the context of the pandemic.

- It considers aid reported to date in the first seven months of 2020 (from January to July inclusive) and compares this to aid reported over the same period in 2019.

- It is primarily focused on commitments [3] – except in the section on overall trends, where disbursements [4] are also considered – as this is more reflective of the decisions that donors are making today, in the context of the Covid-19 crisis.

- As multiple donors may report on the same activity, analysis looks at bilateral donors, IFIs and multilateral institutions separately to avoid double counting issues while allowing for interesting comparison.

For more detailed information on coverage and approach, see the Methodology section at the end of this paper.

Key findings: What trends is IATI data showing?

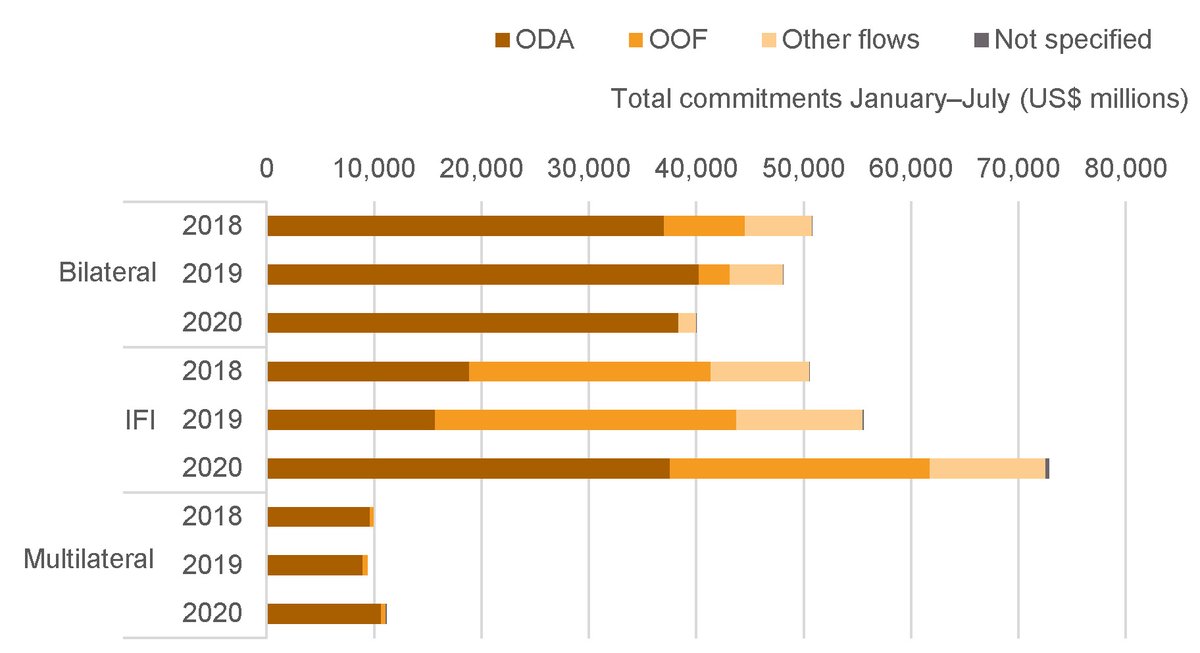

1. Aid commitments from bilateral government donors are falling but increasing significantly from international financial institutions (IFIs).

- Bilateral donors have decreased aid commitments by 17% between 2019 and 2020, including a 5% decline in official development assistance (ODA) commitments. Of the thirteen bilateral donors considered seven have seen ODA commitments fall, with five seeing falls by 40% or more.

- IFIs have increased aid commitments by 31%, driven by a more than doubling (139% growth) in ODA. As a result, ODA makes up over half (52%) of IFI commitments in the first seven months of 2020, up from 28% in 2019.

2. Rising ODA from IFIs is increasing the proportion of aid delivered as loans.

- The vast majority of increases in ODA from IFIs are in the form of concessional loans. For example, the World Bank has increased concessional lending by US$9.7 billion in 2020 compared to the same period in 2019 – an increase of nearly 85%.

3. Neither bilateral donors nor IFIs are increasing the share of aid to low-income countries (LICs), despite this being where recovery will be particularly difficult without international support.

Based on country income:

- Bilateral donors continue to allocate the highest proportions of their aid to LICs. However, in 2020, despite the new challenges and rising needs caused by Covid-19, this remains virtually unchanged at 43% of all commitments.

- In 2020, only 11% of IFI commitments have gone to LICs, a small decrease from 2019 (14%), while middle-income countries (MICs) continue to receive the overwhelming majority (83% of the total).

Based on extreme poverty levels:

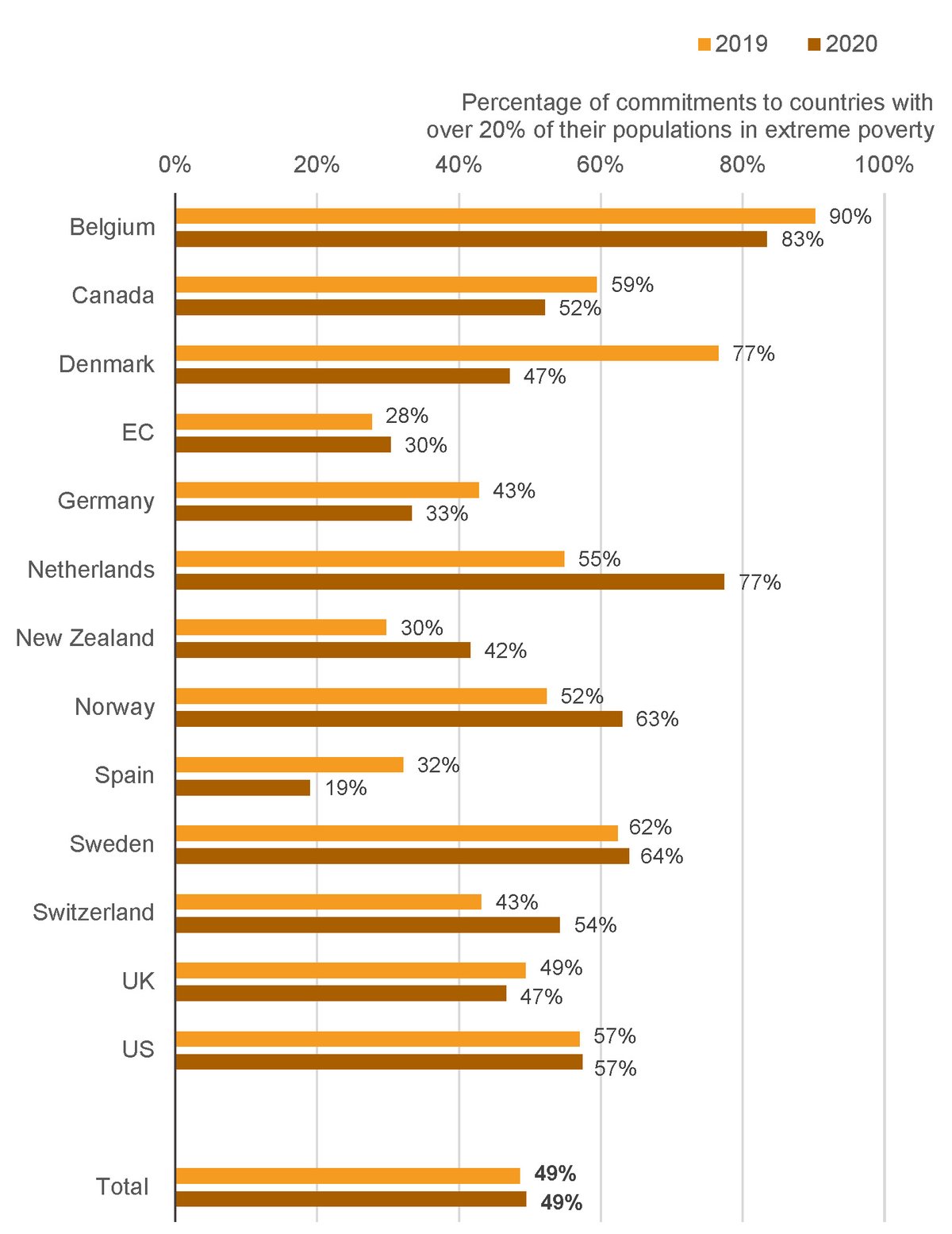

- The proportion of aid commitments from bilateral donors to countries with poverty rates over 20% remains unchanged at 49%, although half the donors analysed have reduced the proportions going to these countries. More than a third (37%) continues to be allocated to countries with extreme poverty rates of less than 5%.

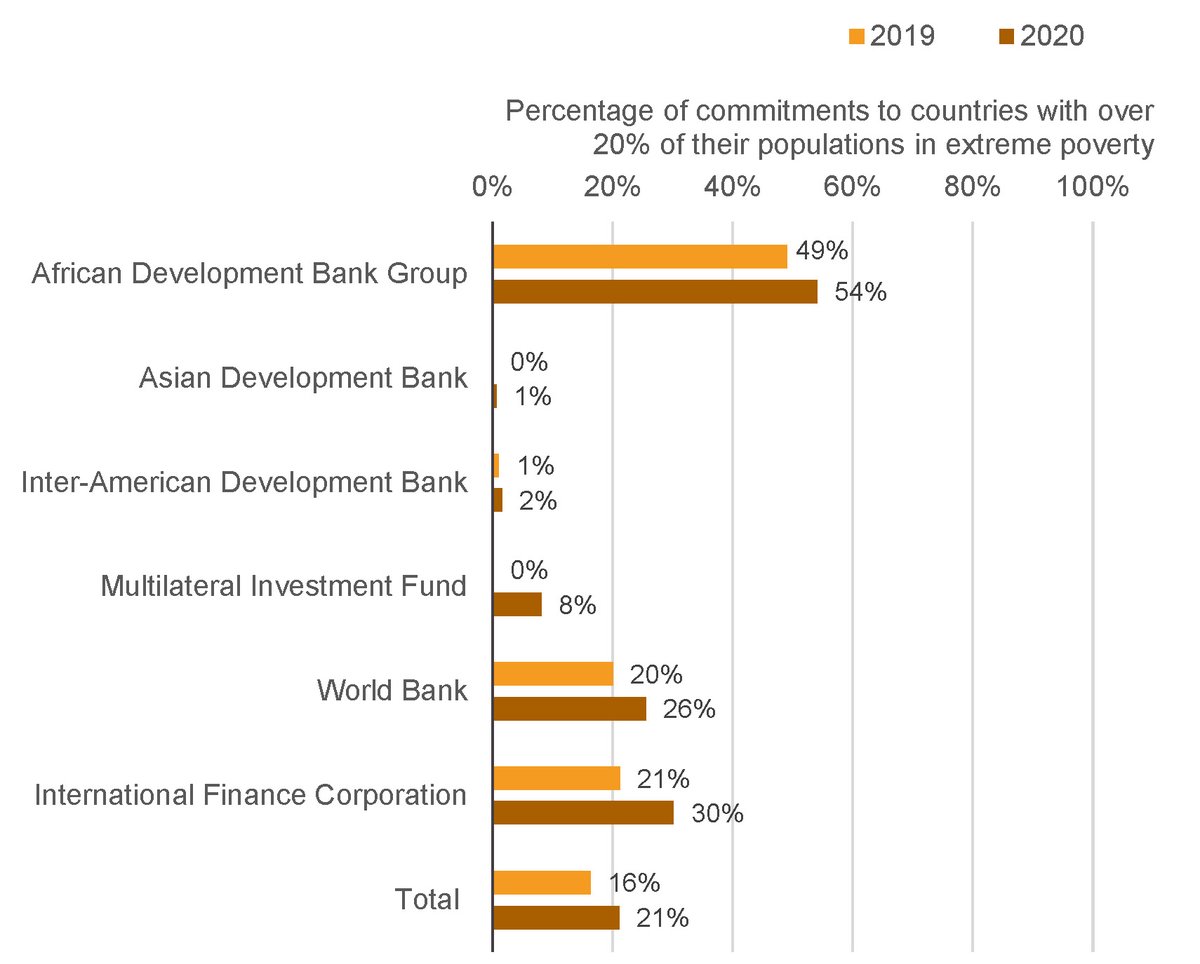

- IFIs have slightly increased the proportions of ODA to high-poverty countries from 16% in 2019 to 21% in 2020, and have decreased by a similar amount in countries with poverty rates of less than 5%, however these still account for 58% of commitments in 2020.

4. IFIs are committing more to social sectors including health, education and social protection, while bilateral donors are increasing commitments to health at the expense of many other areas.

- Bilateral donor commitments to health have increased by 73% (US$3.3 billion) in 2020 compared to the same period in 2019, driven primarily by the US. Almost all other sectors have seen lower commitments, with notable declines in economic sectors and conflict, peace and security.

- IFIs have seen more significant increases across a range of social sectors with commitments to other social infrastructure and services rising by US$7.2 billion (184%) – the majority to social protection. Health and education commitments are higher compared to the same time last year by US$5 billion (156%) and US$3.6 billion (111%) respectively, while water and sanitation is lower by US$972 million (30%). The World Bank in particular, alongside the African Development Bank (AfDB) and Asian Development Bank (ADB), were the most important drivers of this.

IATI data and near real-time reporting

International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) data has now reached the coverage and quality required to inform trends in aid commitments. A critical mass of consistent, timely reporting has been reached with data on approximately 70% of all aid now being consistently published in near real-time. This data is refreshed monthly no more than two or three months in arrears. Over US$12 billion of new funding commitments (US$4 billion from bilateral donors and US$8 billion from IFIs) have been published through IATI since July 2020.

The analysis in this paper is one of the first in-depth applications of this data to assess real-time trends in aid. This represents an important opportunity to better understand the changes and factors driving trends in aid today – and in so doing provides a vital tool to inform policy and decision-making. In conducting this analysis, we at Development Initiatives (DI) are committed to exploring the opportunities, as well as identifying and addressing the challenges, presented by IATI data.

As well as the advantages near real-time data presents, working with IATI data has its challenges.

- It is a voluntary publishing standard, so coverage is not fully comprehensive. This means analysis and the conclusions that can be drawn are only as good as the data reported.

- It is not a curated database [5] so data can change from day to day. This makes for both a more up-to-date picture but also one that is constantly evolving.

- Both the frequency of publishing and the quality of publishing varies, both between donors and within a publisher’s own data. Some donors, for example, accurately disaggregate their monthly commitments, but aggregate disbursements annually.

- Both donor and implementing agencies report on the same activities. This means that adding up amounts between different donor groups is misleading, making comparison between types of actors challenging.

At DI, we have curated our own database of IATI transaction data and established procedures for checking the usability of data (see the Methodology section ). The methodological principle applied here has been to use the best sets of data available for each area of analysis.

Twenty-seven institutions, who between them record US$143 billion of spend in 2019, publish best-practice, near real-time data. A further 18 institutions (with US$55 billion 2019 spend) publish data that has been used selectively in this analysis.

While the IATI standard does include a methodology for tracing funds down the aid delivery chain, it is not implemented consistently. This means that avoiding double counting is an ongoing challenge. Splitting all analysis into three distinct groups of institutions – bilateral donors, IFIs and multilateral institutions – allows for reasonable aggregations within each group, but not between groups.

While some US$12 billion worth of commitments has already been published to IATI for August and September, this study restricts its analysis to comparing the period January to July in 2020. We also look at the same period in 2019 to ensure the widest possible coverage of near real-time publishers. As donors do not necessarily spread their spending evenly across the year, a seven-month snapshot should be treated with some caution if drawing conclusions that are usually based on annual trends.

This briefing focuses mainly on commitments, because this reflects policy decisions being made now in light of the pandemic and its impact. A large volume of 2020 disbursements relate to the meeting of commitments made in previous years but do provide useful information about what money is being spent currently. This paper also draws on other sources to complement and extend analysis where relevant.

Donors and implementing organisations need better visibility of the aid landscape – both their own aid and how it relates to that of other institutions – to be able to act responsibly as they prioritise budgets in the midst of the pandemic.

This briefing sets out the data we can obtain on commitments (and disbursements in the overall picture) to better understand how aid is changing in the first half of 2020. This analysis will be further updated and assessed once data for the full period of 2020 is available.

Aid disbursements and commitments: Overall trends in 2020

Volumes of aid from bilateral donors are falling while dramatic growth from international financial institutions (IFIs) is changing the aid landscape.

Aid commitments and disbursements, mainly in the form of official development assistance (ODA) and other official flows (OOFs) reported from January to July 2020, show that overall volumes are likely to be increasing slightly in the short term. This increase masks significant disparities between institutions and the type of aid.

Bilateral aid does not appear to be responding to the needs created by the pandemic, rather the reverse.

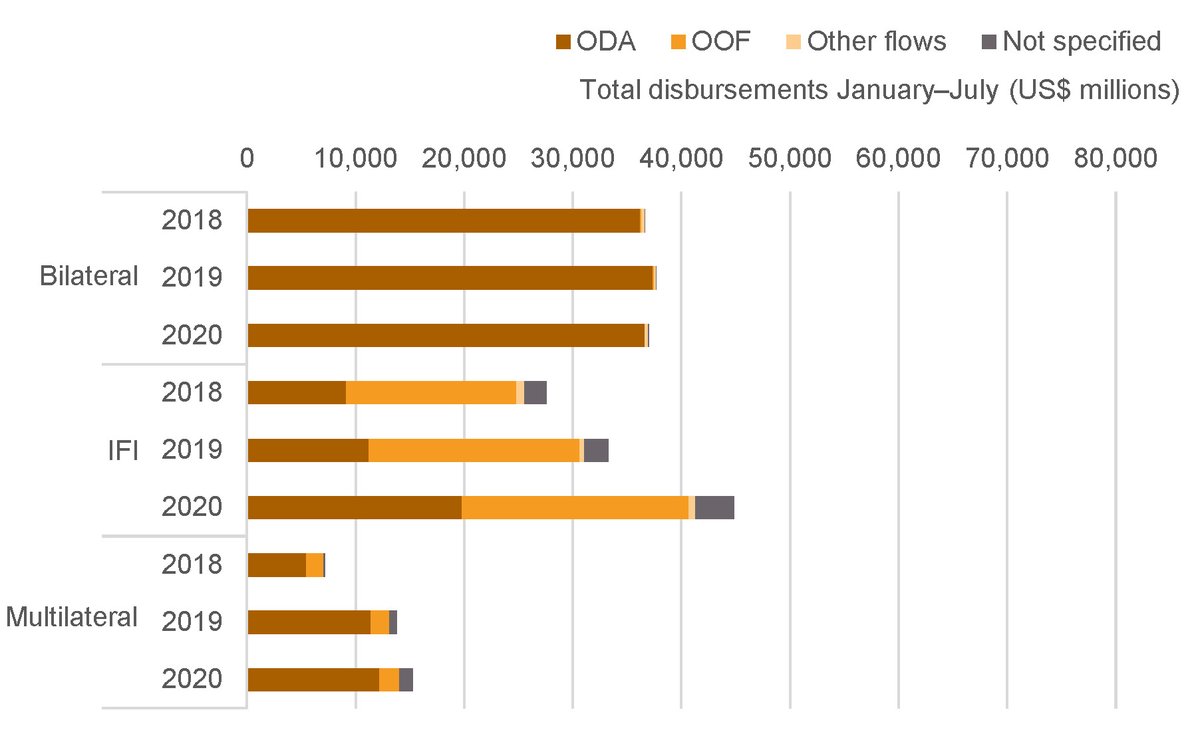

- Total bilateral aid commitments (ODA, OOFs and other flows reported) have fallen by 17% and total disbursements have fallen by 2% in 2020 compared with the same period in 2019.

- ODA commitments and disbursements are currently 5% and 2% lower than the same period in 2019 respectively.

Conversely, aid from IFIs has grown significantly in 2020, accelerating existing trends.

- IFIs have reported a 35% increase in total aid disbursements and a 31% increase in commitments over the same period last year.

- ODA disbursements have grown by 76% and commitments by 139%.

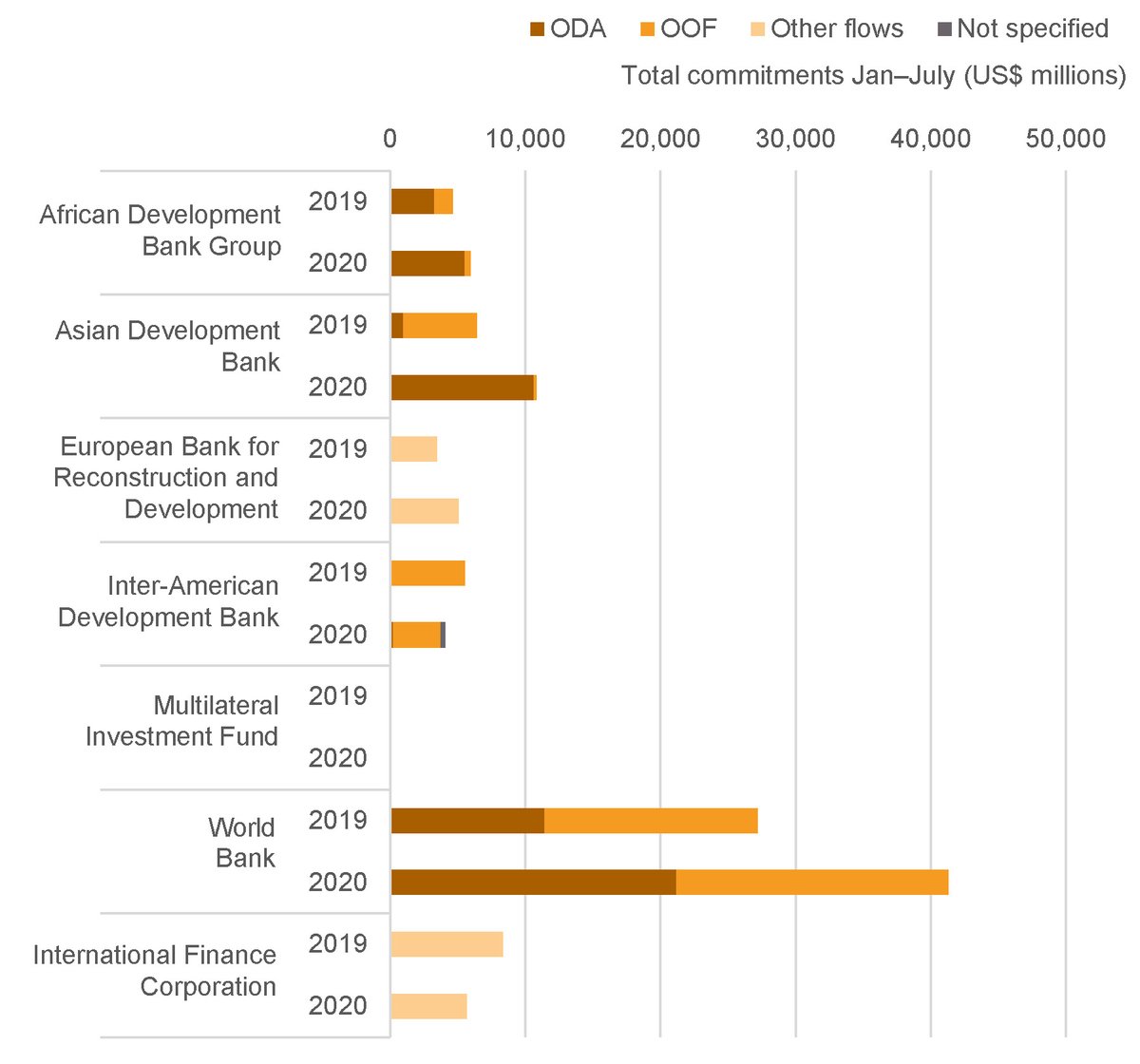

This has substantially changed the profile of IFI development finance, as institutions respond to the current crisis, and significant rises in ODA are the key factor behind these increases. Concessional ODA commitments from IFIs have increased by US$21.8 billion while OOFs have fallen by 13%. This means that ODA represents over half (52%) of IFI commitments in the first seven months of 2020, up from 28% in the same period 2019.

These increases are changing the profile of who is providing ODA – IFIs reported less than half the volume of total bilateral ODA commitments in the first seven months of 2019. Over the same period in 2020, their volumes are almost equal (98%) to the volume of bilateral commitments. But the vast majority of this ODA is being delivered as loans, which has important implications for the kind of aid that will be available to developing countries, as well as raising concerns about debt sustainability.

Multilateral institutions reporting IATI data of sufficient quality for this analysis have reported an 11% increase in disbursements, much of which is ODA. Commitments data is only of sufficient quality for six multilateral institutions; this is not a reliable sample from which to draw wider conclusions about multilateral commitments overall. However, for the six organisations analysed, there has been an 18% increase, the vast majority of which is concessional ODA (see the Methodology section ).

Compared to the same period in 2019, ODA commitments are increasing substantially from IFIs and marginally from multilateral institutions but declining from bilateral donors.

Figure 1: Aid commitments from IFIs have grown substantially in 2020 compared to 2019 – while bilateral donors’ aid commitments have declined

Aid commitments by key bilateral donors, IFIs and multilateral institutions (January–July during the years 2018–2020)

Aid commitments by key bilateral donors, IFIs and multilateral institutions (January–July during the years 2018–2020)

Source: Development Initiatives based on IATI.

Notes: See Table A1 for the full list of bilateral donors, IFIs and multilateral institutions and Table A2 for the full list of flow types included in this chart. IFI = international financial institution; OOF = other official flows.

Disbursements show significant increases from IFIs and minimal change from bilateral donors.

Figure 2: IFI aid disbursement have accelerated while bilateral disbursements have basically flatlined

Aid disbursements by key bilateral donors, IFIs and multilateral institutions (January–July during the years 2018–2020)

Aid disbursements by key bilateral donors, IFIs and multilateral institutions (January–July during the years 2018–2020)

Source: Development Initiatives based on IATI.

Notes: See Table A1 for the full list of bilateral donors, IFIs and multilateral institutions and Table A2 for the full list of flow types included in this chart. IFI = international financial institution; OOF = other official flows.

Which donors and institutions are driving these trends?

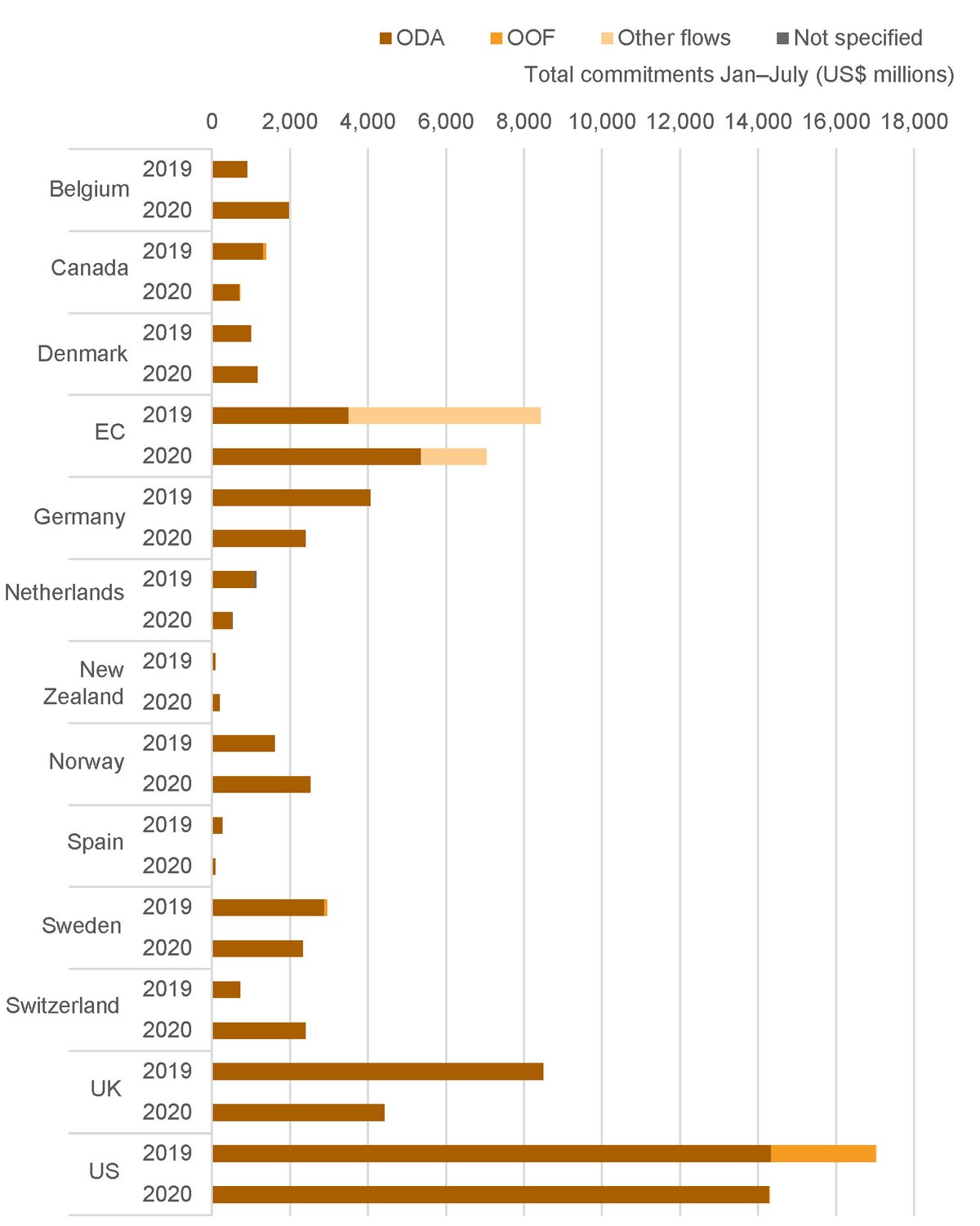

Figure 3: Just over half of bilateral donors have cut aid commitments in 2020 compared to 2019

Bilateral donor aid commitments

Bilateral donor aid commitments

Source: Development Initiatives based on IATI.

Notes: See Table A2 for the full list of flow types included in this chart. OOF = other official flows.

- Six of the fifteen bilateral donors reporting appropriate data are cutting ODA disbursements, with four cutting them by over 20%. The most significant fall in absolute volume comes from the UK (a fall of US$1.4 billion). There are some donors who, conversely, have increased ODA disbursements, notably the European Commission (EC) by 32% compared to 2019.

- Seven of the thirteen bilateral donors included in commitments analysis have recorded falls in ODA commitments, with five seeing falls by 40% or more. Significant absolute falls are noted particularly for the UK at US$4.1 billion (48%). [6] As with disbursements, the EC is offsetting the overall drop with an additional US$1.86 billion, representing a 53% increase compared to 2019.

Figure 4: The World Bank, and Asian Development Bank, are driving substantial increases in IFI aid commitments

IFI aid commitments

IFI aid commitments

Source: Development Initiatives based on IATI.

Notes: See Table A2 for the full list of flow types included in this chart. IFI = international financial institution; OOF = other official flows.

- Significant increases in ODA from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) are driving increases in IFI disbursements. [7]

- Substantial increases in IFI commitments are being driven by increases in ODA from the World Bank and the ADB (both increasing ODA commitments by US$9.7 billion, driven by Covid-19 response activities).

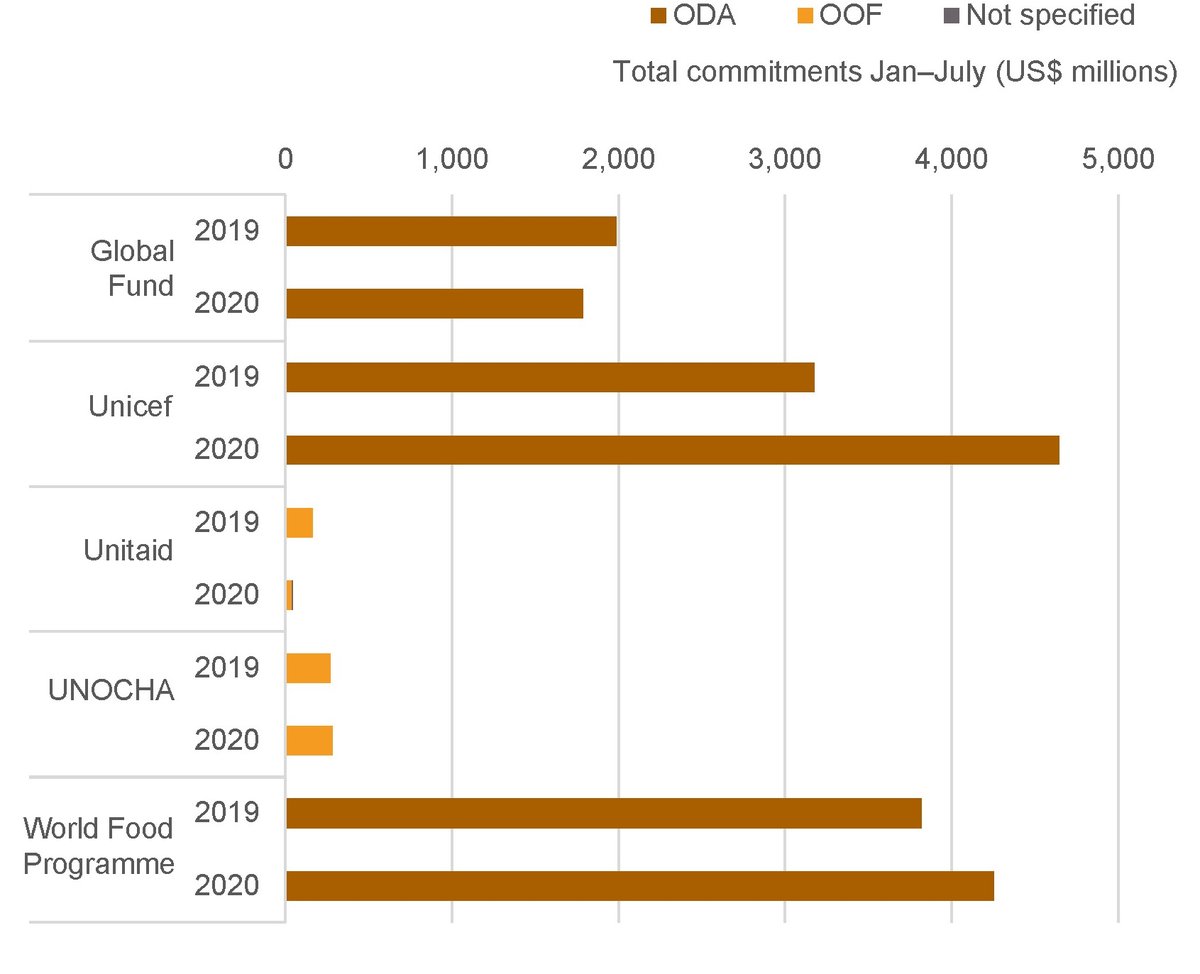

Figure 5: Limited data from multilaterals shows an 18% increase in commitments, the vast majority of which is concessional ODA

Multilateral institutions aid commitments

Multilateral institutions aid commitments

Source: Development Initiatives based on IATI.

Notes: See Table A2 for the full list of flow types included in this chart. OOF = other official flows; UNFPA = UN Population Fund; UNOCHA = United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

- Commitments data is reported to a sufficient standard for this analysis by five multilateral institutions. Of those, three have increased combined ODA and OOF commitments and two have decreased these commitments. Notably, the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) has reported an increase of US$1.5 billion in ODA commitments, 46% more than 2019, and this is a significant factor in the overall commitments from multilateral institutions remaining steady.

Implications

IFIs, and the World Bank and regional development banks in particular, have been the most important drivers of 2019–2020 changes in aid observed so far. Substantial increases in ODA from these institutions, largely in the form of concessional lending, paired with the current flatlining of bilateral aid in aggregate, are presenting a new balance between different providers of aid.

While IFIs can play an important role in supporting broader economic stability and jobs, and are increasingly engaged in supporting human capital, their aid is typically less concessional, and less targeted to the poorest people and places compared to bilateral aid. [8] Such institutions will need to demonstrate better targeting of more concessional aid should such increases be sustained.

Decreases from a broad range of bilateral donors in both commitments and disbursements are significant and concerning. This means that less money is reaching the poorest people and countries at a time when it is needed most to deal with the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Falls in aid volumes, if they continue, risk a lost decade precisely as a decade of action [9] is needed to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), pledged just last year. Falling volumes also heighten the need for aid to be much more focused on where it is needed most, and in the sectors that most benefit the poorest people and places.

Aid targeting towards poverty: 2020 trends

The international response to the Covid-19 pandemic does not seem to be driving a greater focus on the poorest people and places, with no overall significant shifts in targeting from bilateral donors or international financial institutions (IFIs) based on country income or extreme poverty levels.

For this analysis, and in subsequent sections, we look at total aid commitments reported including official development assistance (ODA), other official flows (OOFs) and any other flows for development reported to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), focusing on bilateral donors and IFIs. Multilateral institutions are excluded from the analysis as data quality is not sufficient to give an indication of overall trends.

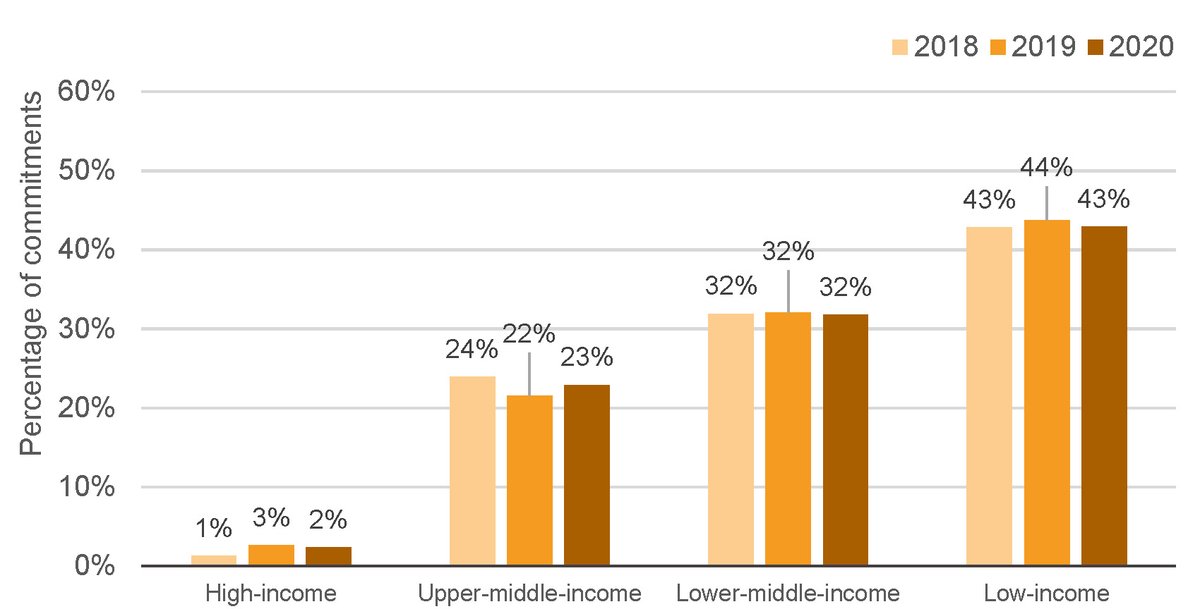

Country income groupings and aid commitments

Aid commitments from bilateral donors remain highest in low-income countries (LICs) and from IFIs in middle-income countries (MICs). However, the proportion of aid to the poorest countries has fallen marginally for both bilateral donors and IFIs.

The distribution of country-allocable aid commitments [10] from bilateral donors has remained largely unchanged, with 43% allocated to LICs (down marginally from 44% in 2019) with 32% to lower middle-income countries (LMICs) and 23% to upper middle-income countries (UMICs) (up one percentage point from 2019).

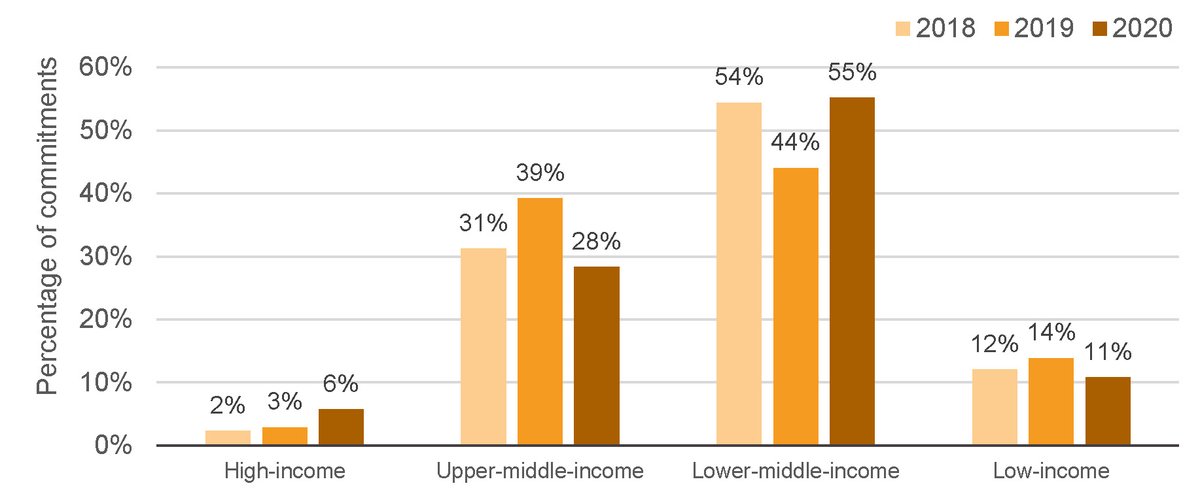

IFIs continue to commit a much higher proportion to MICs, comprising over 80% of total commitments in 2020, with 55% to LMICs and 28% to UMICs. Only 11% of commitments from IFIs went to LICs, a small decrease compared to 2018 and 2019 levels.

Figure 6: Bilateral aid commitments to the poorest countries have not increased

Comparison of aid to country income groupings for bilateral donors (January–July during the years 2018–2020)

Comparison of aid to country income groupings for bilateral donors (January–July during the years 2018–2020)

Source: Development Initiatives based on IATI and World Bank country income groups.

Note: See Table A1 for the full list of bilateral donors included in this chart.

Figure 7: IFI commitments to LICs have actually dropped between 2019 and 2020 to date

Comparison of aid to country income groupings for IFIs (January–July during the years 2018–2020)

Comparison of aid to country income groupings for IFIs (January–July during the years 2018–2020)

Source: Development Initiatives based on IATI and World Bank country income groups.

Notes: See Table A1 for the full list of IFIs included in this chart. IFI = international financial institution; LIC = low-income country.

In focus

Bilateral donors

- Falls in absolute volumes of bilateral commitments have been shared relatively equally across income groups. However, there has been a small shift away from LICs in favour of UMICs.

- There is substantial variation between donors. Of the thirteen bilateral donors analysed, eight decreased the proportion of commitments going to LICs, while four increased it.

International financial institutions

- Commitments to LICs have risen marginally in volume terms between 2019 and 2020 (by US$0.3 billion), but the share reduced due to the much larger increases in commitments to LMICs and, to a lesser extent, high-income countries (HICs). This proportional decrease to LICs – from 14% in 2019 to 11% in 2020 – is being largely driven by decreases in share of commitments going to these countries from the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the World Bank (including the International Finance Corporation (IFC)).

- The increase to LMIC’s share of IFI commitments (up from 44% to 55% in 2020) reverses the decrease seen from 2018 to 2019 (down from 54% to 44%). This change was primarily driven by a US$11.7 billion (103%) increase from the World Bank.

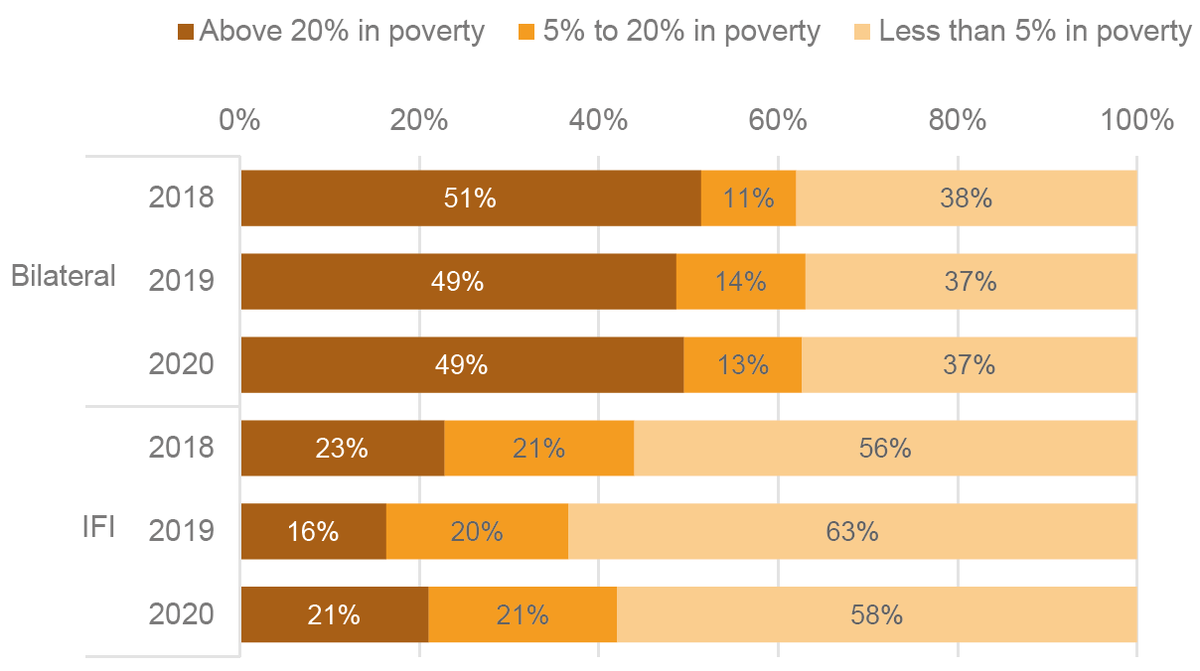

Levels of poverty

Countries with the highest levels of poverty continue to receive the largest proportion of bilateral donors’ aid commitments – half of total commitments of country-allocable aid (49%). However, proportions have not changed compared to 2019, and over a third (37%) has continued to go to countries with poverty rates of less than 5%.

The proportion of country-allocable aid from IFIs to high-poverty countries has historically been much lower than that of bilateral donors. In the January to July period in 2019, this accounted for 16% of commitments. Alongside the increases seen in ODA commitments, this has risen in 2020, accounting for a fifth of commitments. Conversely, the proportion of commitments to countries with low rates of poverty has fallen by a similar margin, but 58% of IFI commitments continue to go to countries with poverty levels below 5%.

Figure 8: The proportion of aid commitments to countries with the highest rates of extreme poverty have not grown, except for a small increase from 16% to 21% from IFIs

Comparison of aid by poverty banding between bilateral donors and IFIs (January–July during the years 2018–2020)

Comparison of aid by poverty banding between bilateral donors and IFIs (January–July during the years 2018–2020)

Source: Development Initiatives based on IATI and World Bank PovcalNet.

Notes: See Table A1 for the full list of bilateral donors, IFIs and multilateral institutions included in this chart. IFI = international financial institution. People living in extreme poverty are defined as living on less than $1.90 a day (2011 PPP).

Figure 9: More than half of bilateral donors reported a fall in commitments to countries with extreme poverty rates over 20%

Comparison of aid by poverty banding by individual bilateral donors (January–July 2019 and 2020)

Comparison of aid by poverty banding by individual bilateral donors (January–July 2019 and 2020)

Source: Development Initiatives based on IATI and World Bank PovcalNet.

Note: EC = European Commission.

Figure 10: All six IFIs have reported small increases to countries with higher rates of extreme poverty

Comparison of aid by poverty banding by individual IFIs (January–July 2019 and 2020)

Comparison of aid by poverty banding by individual IFIs (January–July 2019 and 2020)

Source: Development Initiatives based on IATI and World Bank PovcalNet.

Note: IFI = international financial institution.

In focus

Within both bilateral donors and IFIs, there are significant differences between individual donors’ shifting trends in targeting countries with the highest rates of extreme poverty.

Bilateral donors

- The proportion of country-allocable aid from bilateral donors going to countries with extreme poverty rates over 20% remained constant between 2019 and 2020, at 49% (down from 51% in 2018). But more than half – eight out of the thirteen bilateral donors studied – reported a fall in absolute volumes, with the largest falls reported by Germany, the UK and Sweden. Figure 9 shows six bilateral donors have reported lower proportions of their country-allocable commitments being allocated to countries with high poverty rates.

- Over a third (37%) of commitments have gone to countries with poverty rates of less than 5%.

International financial institutions

- All six IFIs included in the analysis reported a rise in the proportion of their country-allocable aid targeting countries with high levels of extreme poverty. Most notably, the World Bank increased its proportion of aid to these countries from 20% to 26% between 2019 and 2020, and the African Development Bank (AfDB) from 49% to 54%.

Implications

The focus of aid on low income countries and those with the highest levels of poverty is not improving across many donors, despite the new and growing challenges for the poorest countries posed by the Covid-19 pandemic. A failure to target aid resources effectively could push some of these countries even further behind, as the poorest countries are facing falling domestic revenues and are often highly reliant on other international flows, such as foreign direct investment (FDI), remittances and tourism receipts that have been hit hard by the pandemic. In this context, aid represents a vitally important support, but the data so far does not suggest that aid providers are rising to the challenge of targeting additional resources to these countries. [11]

Aid commitments to sectors: 2020 trends

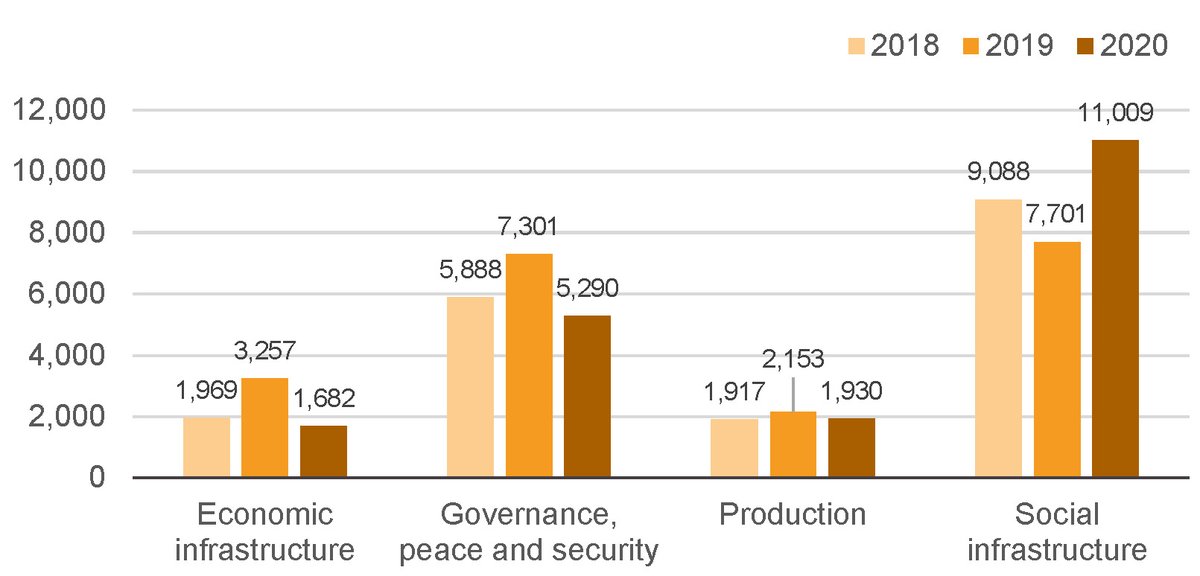

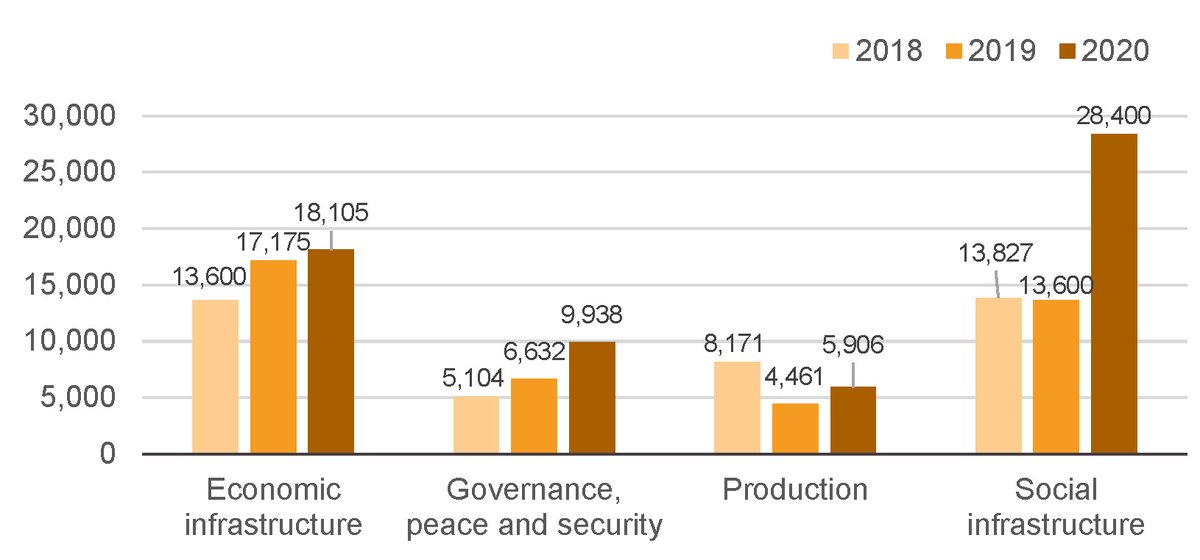

Increases in bilateral aid to health currently come at a cost to most other sectors, while international financial institutions (IFIs) are shifting focus towards social sectors, driven particularly by increases in funding for social protection and health

Increased spending on social sectors by bilateral donors in 2020, led by health (73% increase compared to the same period in 2019), appears to have come at the cost of other economic, productive and governance sectors, where commitments are falling in volume and percentage terms. Social sectors have seen a combined increase of 43% compared to the same period last year (by US$3.3 billion), while commitments in economic, governance and production areas have fallen, but with significant variation in specific sectors.

Growth across a number of social sectors has shifted the balance of IFI investments between social and economic sectors. In 2018 and 2019, IFI commitments largely came under economic and social activities. In 2020, to date, aid to social sectors has more than doubled compared to the same period last year, increasing by US$14.8 billion. Unlike bilateral donors, however, commitments to other areas have also increased alongside health, and social protection, if not at the same scale.

Figure 11: Bilateral donors have increased aid commitments to health, driving increases in social sectors, but at the expense of other sectors

Changes by bilateral donors in broad sector focus (January–July during the years 2018–2020)

Changes by bilateral donors in broad sector focus (January–July during the years 2018–2020)

Source: Development Initiatives based on IATI.

Note: See Table A1 for the full list of bilateral donors included in this chart.

Figure 12: Aid commitments from IFIs have increased across a range of sectors, with a particular focus on social sectors

Changes by IFIs in broad sector focus (January–July during the years 2018–2020)

Changes by IFIs in broad sector focus (January–July during the years 2018–2020)

Source: Development Initiatives based on IATI.

Notes: See Table A1 for the full list of IFIs included in this chart. IFI = international financial institution.

Health has driven increases in bilateral social sector commitments in 2020. With the exception of small increases for education and trade and tourism, commitments to all other sectors, including other social sectors, are lower compared to the same period in 2019.

Among IFIs, the World Bank has been a significant driver of change across many social sectors, including notably increased spending on health and education. Social protection, however, has seen the largest increases. This has been driven by the World Bank and Asian Development Bank (ADB), [12] and accounts for the vast majority of the US$7.2 billion increases in the wider ‘other social infrastructure and services’ reporting category.

Conversely, water and sanitation is notable as the only social sector seeing IFI commitments fall in absolute terms, with volumes US$0.97 billion lower than the same period in 2019. With the exception of transport and storage, and to a much lesser extent in absolute terms, trade and tourism, commitments have increased to all other sectors, although they are mostly outpaced by growth in social sectors.

Figure 13: Bilateral donors have focused aid commitments on health at the expense of other sectors while IFIs have seen increases across the board with a proportionally greater focus on social protection and health

Sector percentage changes for bilateral donors and IFIs (January–July 2019 and 2020)

Sector percentage changes for bilateral donors and IFIs (January–July 2019 and 2020)

Source: Development Initiatives based on IATI.

Notes: See Table A1 for the full list of bilateral donors and IFIs included in this chart. IFI = international financial institution.

In focus

Bilateral donors

- Health received by far the largest increase in commitments to any social sector – a US$3.3 billion (73%) rise in commitments over the same 2019 period. This increase came mainly from the US, almost doubling its commitments to the sector. The UK and Germany, however, have seen their health commitments fall.

- Smaller increases in education (US$272 billion in total) have been driven by the European Commission (EC). The absence of any notable increase in aid to social protection has left commitments in other social infrastructure and services 30% lower than the same period last year (down US$242 million). Most sectors outside the social sectors have seen lower volumes of commitments compared to the same period last year, most notably for conflict, peace and security, and banking and business, with current reported commitments US$1.6 billion and US$1 billion lower respectively.

International financial institutions

- The large increase in spending on social sectors by IFIs has been broad across a number of sectors, led by a US$7.2 billion (184%) increase in other social infrastructure and services – mostly to social protection. Health and education commitments are higher compared to the same time in 2019 by US$5 billion (156%) and US$3.6 billion (111%) respectively, while water and sanitation is lower by US$972 million (30%).

- The World Bank has been the largest single factor in the changes in IFI commitments on social sectors. Compared to January to July 2019, it has increased health commitments by US$4.3 billion (154%), education by US$2 billion (87%) and other social infrastructure and services by US$3.9 billion (140%).

Implications

More IFI investment in social sectors – social protection and health in particular – is notable. Given all these increases have come in the form of loans (see the section ‘ Grants and loans: 2020 trends ’), this will require further scrutiny. The scale of these increases, which come at a time when bilateral aid is falling in certain sectors, may start to shift the nature of financing used to support delivery of critical human development and human capital sectors, including in the poorest countries.

The greater relative importance of IFIs in delivering social sector aid is also a potential issue given their less strong focus on the poorest countries.

Increases in spending by the World Bank in social sectors represents one of the most significant shifts in the sector financing landscape in 2020. If sustained, alongside falls in bilateral aid to certain social sectors, the World Bank’s proportional significance in financing human capital will grow, alongside its key role in economic development.

While increased spending on health is expected and appropriate in the current crisis, it is also important to note that decreases in other sectors – water and sanitation for example – could, if they continue, risk undermining medium-term recovery and longer-term progress in both economic and human development. Whether these changes are long or short-term will depend on the choices that donors make in the near future – both on overall volumes of aid and how these volumes are allocated.

Grants and loans: 2020 trends

The substantial increase in commitments from international financial institutions (IFIs) and fall in commitments from bilateral donors is shifting the grant–loan profile of aid.

The donor profile of lending has remained largely unchanged in 2020, with the majority of loans being provided through IFIs and bilateral agencies primarily delivering aid through grants.

There is no evidence of bilateral donors who do not usually provide loans starting to do so. It should be noted, however, that the majority of bilateral donors that do traditionally offer official development assistance (ODA) through loan modalities, such as Japan, France and South Korea, either do not report them to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), or their data has not been incorporated into this analysis for reasons of quality and consistency. Similarly, Germany has not yet reported any lending commitments to IATI in 2020. Therefore, it is currently difficult to assess how volumes of bilateral aid provided as loans may have changed.

Clearer reporting from IFIs reveals that concessional lending is scaling up substantially from these institutions. As detailed in the section ‘ Aid disbursements and commitments: Overall trends in 2020 ’, in aggregate, the substantial increase in IFI commitments in 2020 has derived entirely from an increase in ODA, with volumes of other official flows (OOFs) falling marginally. In 2019, ODA accounted for less than a third of IATI-reported IFI commitments. In 2020, it accounted for 52%, with volumes of ODA increasing by US$21.8 billion – a 139% increase.

The vast majority of ODA increases from IFIs was delivered in the form of loans. Lending from the World Bank in 2020 has increased, as of July 2020, by US$14.1 billion over the same period in 2019. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has increased by US$4.3 billion and the African Development Bank (AfDB) by US$1.8 billion. In each case, these represent increases of over 40% compared to the same period in 2019.

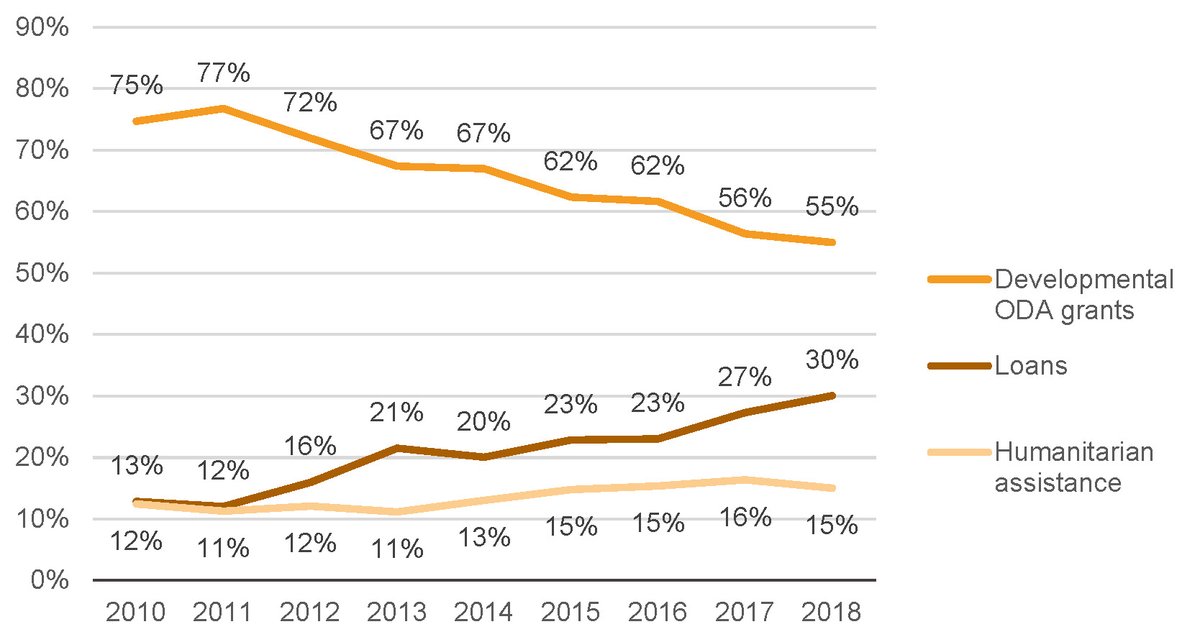

However, together with falling volumes of bilateral aid that is traditionally delivered as grants, it is clear that the concessionality of aid as a whole, notably the balance between grants and loans, is swinging further to the latter. This is also true for least developed countries (LDCs), where analysis by Development Initiatives of the latest complete OECD ODA release showed that ODA loans have grown substantially in the past decade – more than doubling from 13% of ODA in 2010 to 30% in 2018. [13]

Figure 14: In LDCs, donors have switched some ODA from grants to loans

Proportional changes in ODA loans, grants and humanitarian assistance 2010–2018

Proportional changes in ODA loans, grants and humanitarian assistance 2010–2018

Source: Development Initiatives, based on OECD DAC data. The figure is drawn from: /58d0d1#48860ba0 [14] .

Note: LDC = least developed country.

Implications

Debt ratios, notably for many of the poorest countries, have grown at unprecedented rates over the last decade, and debt servicing as a proportion of non-grant revenues in the LDCs has more than doubled since 2010. [15] Increased pressure on public finances due to additional spending needs as a result of the pandemic, combined with a collapse in revenue (particularly for commodity exporters and tourism-dependent countries) is driving new public and private borrowing that will push debt ratios even higher.

Concessional lending constitutes a legitimate and important source of international finance for developing countries, particularly where urgent needs can be met quickly and flexibly. However, aid should help ameliorate, not contribute to, the impacts of rising debt levels. Therefore, the scale of the increase in such lending, together with the concomitant fall in grant-based assistance, will demand greater scrutiny of the level of concessionality with which it is being provided, as well as where and how it is being deployed.

Conclusions

Using real-time data published to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), this paper has highlighted a number of trends emerging in the first half of 2020 on the scale of aid, the sectors and places it is being directed to, and the diverging practices of different development actors as they face the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic.

- Bilateral aid is declining, albeit slightly to date, with a number of government donors already reporting lower volumes compared to the same period last year, while international financial institutions (IFIs) are playing an ever more important role as they frontload spending. Sustaining IFI aid at such levels would require substantial and supplemental replenishment from bilateral donors further shifting the focus of their aid.

- There is no evidence of the pandemic improving the targeting of aid commitments towards the poorest countries and those in most need. These countries are often most dependent on international support, so insufficient targeting of aid undermines both their ability to manage the immediate impacts of the pandemic and address longer-term risks of being further left behind. If the more prominent role of IFIs is sustained, improvements in targeting the poorest countries will be essential.

- As would be expected, commitments to health are growing dramatically across bilateral and IFI aid to tackle the immediate impacts of the pandemic. For many bilateral donors, this is coming at the expense of other critical social sectors such as social protection (currently supported predominantly by a limited set of donors), which is critical for protecting the poorest people and building resilience to future crises. This will become an increasing concern the longer such funding patterns continue.

Such trends, however, only reflect the first seven months of 2020. There is time for course correction to drive a better response to the pandemic and to ensure that aid plays a vital role in recovery. With greater visibility of what is happening to aid now, decision-makers who hold the budgets and make aid allocation decisions, can take action.

Recommendations

At Development Initiatives (DI), we will continue to monitor and share trends emerging in aid including through our analysis of real-time International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) data. It may be too soon to draw firm conclusions and recommendations from what is currently observed. However, on the basis that these trends may continue, recommendations can be made for both bilateral donors and international financial institutions (IFIs).

Recommendations for bilateral donors

- Commit to maintaining aid levels and providing highly concessional aid. Where cuts are made, as seems likely given announcements by individual donors and the trends observed in this paper, they should be based on an evidence-led analysis of need, and protect spending on the programmes that are most effective in targeting poverty, This should result in rising proportions of aid being directed to the poorest countries at greatest risk of being left behind.

- Ensure that cuts to other critical sectors as a result of increased health spending are not prolonged and seek to more effectively coordinate in order to deliver a more balanced portfolio of support across sectors that addresses both short and longer-term needs.

Recommendations for IFIs

- Improve the targeting of spending, and official development assistance (ODA) in particular, to the places that need it most. If IFIs continue to grow in importance in the development finance landscape, they will require substantial funding to replenish or increase spending in the future but they will need to demonstrate that such resources will be better targeted at low-income countries (LICs) and countries with high poverty rates.

- Similarly, they will need to demonstrate a commitment to provide more concessional aid for the poorest countries, including grants and lending at higher rates of concessionality, alongside plans to manage and limit debt accumulation.

Coordination of international effort will become increasingly important as challenges continue to rise and resources become scarcer. Better data from more actors, and multilateral organisations in particular, will substantially improve our real-time understanding of aid and our ability to manage it.

It will also better assist recipient country governments to manage the resources flowing across their borders. This can strengthen our ability to respond effectively, making the most of the limited resources to tackle both long-term development challenges and mitigate the worst effects of the global crisis sparked by the pandemic.

While many donors and organisations are reporting usable data, and should be commended, there is much room for improvement. Many publishers have made substantial efforts in recent years to improve the quality of their IATI data, making this real-time analysis is possible.

Now is the time to improve publishing standards across all development actors. Practically, this means publishing data monthly in near real-time (two to three months in arrears at a maximum), consistent reporting across commitments and disbursements, and consistently using all the OECD DAC classifications.

Methodology

This section outlines the methodology used in this analysis of near real-time data on aid during the first half of 2020. The data is used to show how commitments are changing in light of the Covid-19 pandemic, and highlight where these impact hardest on the poorest people and places.

Initial dataset

This paper analyses transactions published to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI). A direct download was taken (on 8 October 2020) of all the data in the IATI registry. [16] These transactions are filtered by:

- the year 2018 onwards

- the first seven months of each year (January to July)

- transaction type marked as ‘C’ or ‘2’ for commitments and ‘E’, ‘D’, ‘R’, ‘QP’, ‘3’, ‘4’, ‘7’ or ‘8’ for disbursements.

Analysis

The analysis focuses on a selected group of key bilateral donors, international financial institutions (IFIs) and multilateral institutions reporting to IATI. The quality of data provided by these donors for both disbursements and commitments is assessed and adjudged to be usable or not.

In some cases, donors position all of their commitments/disbursements in a singular month – United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), Sweden and Switzerland for disbursements and the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) and Switzerland for commitments. To adjust for this, we use a pro-rata method to spread these funds across all months between January and July.

Table A1: Key bilateral donors, IFIs and multilateral institutions used in the analysis of IATI disbursements and commitments

| Institutions | Disbursements | Commitments |

|---|---|---|

| Bilateral donors | ||

| Australian Aid | Yes | No |

|

Belgium – Directorate-General for Development Cooperation and

Humanitarian Aid (DGD) |

Yes | Yes |

| Canada – Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD) | Yes | Yes |

| Denmark – Ministry of Foreign Affairs | Yes | Yes |

| European Commission (EC) – Development and Cooperation – EuropeAid | Yes | Yes |

|

EC – Directorate-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement

Negotiations (DG NEAR) |

Yes | Yes |

| EC – Service for Foreign Policy Instruments (FPI) | Yes | Yes |

| EC – European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO) | Yes | Yes |

| EC – European Investment Bank (EIB) | No | Yes |

| Finland – Ministry for Foreign Affairs | Yes | No |

|

Germany – Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development

(BMZ) |

No | Yes |

| Germany – Federal Foreign Office | Yes | Yes |

| Netherlands – Enterprise Agency (RvO) | Yes | Yes |

| Netherlands – Ministry of Foreign Affairs (DGIS) | Yes | Yes |

| New Zealand – Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade | Yes | Yes |

| Norway – Norway Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) | Yes | Yes |

| Spain – Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID) | Yes | Yes |

| Sweden – Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) | Yes | Yes |

| Switzerland – Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) | Yes | Yes |

| UK – British Council | Yes | Yes |

| UK – Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) | Yes | Yes |

| UK – Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) | Yes | No |

| UK – Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) | Yes | Yes |

| US – The Federal Government of the United States | No | Yes |

| US – US Agency for International Development (USAID) | Yes | Yes |

| International financial institutions (IFIs) | ||

| African Development Bank Group (AfDB) | Yes | Yes |

| Asian Development Bank (ADB) | Yes | Yes |

| European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) | Yes | Yes |

| International Finance Corporation (IFC) | No | Yes |

| Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) | Yes | Yes |

| Multilateral Investment Fund (MIF) | Yes | Yes |

| World Bank | Yes | Yes |

| Multilateral institutions | ||

| Global Fund | Yes | Yes |

| International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) | Yes | No |

| International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) | Yes | No |

| United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) | Yes | No |

| UN Population Fund (UNFPA) | No | Yes |

| United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) | Yes | Yes |

| United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) | Yes | No |

| Unitaid | Yes | Yes |

| United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) | Yes | Yes |

| UNOCHA – Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) | Yes | No |

| United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) | Yes | No |

| World Food Programme (WFP) | Yes | Yes |

Source: Development Initiatives based on IATI.

Notes: IFI = international financial institution; IATI = International Aid Transparency Initiative.

Aid disbursements and commitments: analysis

In the section ‘ Aid disbursements and commitments : Overall trends in 2020 ’, we analyse overall aid commitments and disbursements to better understand how aid is being affected in the short term (through disbursements) and the longer term, as reflected in policy decisions being made now (through commitments).

In this paper, we use the term ‘aid’ as per its use in IATI data to capture all humanitarian and development assistance. In this context, aid is much broader than the official development assistance (ODA) definition used by the OECD DAC , and includes other official flows (OOFs) and any other development flows reported by official actors to IATI.

We analyse these aid flows disaggregated by ODA, OOFs and other flows to consider whether the aid portfolio composition is changing, as well as just volume changes. The full list of flow types included are summarised in Table A2, along with their respective grouping.

Table A2: Flow types considered in the analysis of IATI disbursements and commitments

| Flow type | Grouping |

|---|---|

| ODA | ODA |

| Other official flows (OOF) | OOF |

| Non-export credit OOF | OOF |

| Private development finance | Other flows |

| Private market | Other flows |

| Non flow | Other flows |

| Other flows | Other flows |

Note: IATI = International Aid Transparency Initiative.

Throughout the rest of the paper, we consider commitments as they reflect the policy decisions being made now and thus speak to the decisions being made by key actors in the context of the Covid-19 crisis. Disbursements, however, are more reflective of historic policy decisions but also give important indications of the amount of aid and how aid is being spent now.

Aid targeting towards poverty: analysis

In the section ‘ Aid targeting towards poverty: 2020 trends ’, we consider the targeting of aid commitments within each of our donor classifications (bilateral, IFI, multilateral) to the needs of the poorest people and places. For this task, we analyse aid allocated to specific countries by both World Bank country income group [17] and poverty rate.

We focus on bilateral and IFI donors since these have the strongest breadth of reporters and quality of reporting. It is also important to note that, although IFIs report in excess of 90% of their commitments to specific countries, bilateral donors only report half, with the remainder being specified to regions or else unspecified. We present recipient country analysis as proportions to isolate the change in portfolio away from changes in volume.

Aid commitments to sectors: analysis

In the section ‘ Aid commitments to sectors: 2020 trends ’, the analysis focuses on commitments specified to sectors using the OECD DAC sector groupings. To analyse more macro trends, we group these into four broader categories to interrogate policy shifts at that level, as specified in Table A3.

Table A3: OECD DAC vocabulary groupings considered in the analysis of IATI disbursements and commitments

| OECD DAC | Grouping | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Banking and financial services | Banking and business | Economic infrastructure |

| Business and other services | Banking and business | Economic infrastructure |

| Communications | Communications | Economic infrastructure |

| Energy distribution | Energy | Economic infrastructure |

| Energy generation, non-renewable sources | Energy | Economic infrastructure |

| Energy generation, renewable sources | Energy | Economic infrastructure |

| Energy policy | Energy | Economic infrastructure |

| Hybrid energy plants | Energy | Economic infrastructure |

| Nuclear energy plants | Energy | Economic infrastructure |

| Transport and storage | Transport and storage | Economic infrastructure |

| Conflict, peace and security | Conflict, peace and security | Governance, peace and security |

| Government and civil society – general | Government and civil society – general | Governance, peace and security |

| Agriculture | Agriculture | Production |

| Construction | Industry, mining and construction | Production |

| Fishing | Agriculture | Production |

| Industry | Industry, mining and construction | Production |

| Mineral resources and mining | Industry, mining and construction | Production |

| Tourism | Trade and tourism | Production |

| Trade policies and regulations | Trade and tourism | Production |

| Basic education | Education | Social infrastructure |

| Basic health | Health | Social infrastructure |

| Education, level unspecified | Education | Social infrastructure |

| Health, general | Health | Social infrastructure |

| Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) | Health | Social infrastructure |

| Other social infrastructure and services | Other social infrastructure and services | Social infrastructure |

| Population policies/programmes and reproductive health | Health | Social infrastructure |

| Post-secondary education | Education | Social infrastructure |

| Secondary education | Education | Social infrastructure |

| Water supply and sanitation | Water and sanitation | Social infrastructure |

Note: IATI = International Aid Transparency Initiative.

Grants and loans: analysis

The section ‘ Grants and loans: 2020 trends ’ focuses on the trends in concessionality from donors and more specifically, the split between grants and loans. Within IATI, aid commitments are disaggregated by finance type. These can be broadly categorised as ‘Grants’ and ‘Loans’, as well as small quantities of ‘Equity Investments’ and ‘Guarantees’. Table A4 specifies how these have been classified.

Table A4: Finance types considered in the analysis of IATI disbursements and commitments

| Finance type | Grouping |

|---|---|

| Aid loan excluding debt reorganisation | Loan |

| Standard loan | Loan |

| Investment-related loan to developing countries | Loan |

| Bank export credits | Loan |

| Debt forgiveness: ODA claims (I) | Grant |

| Standard grant | Grant |

| Common equity | Equity Investment |

| Guarantees/insurance | Guarantees |

Note: IATI = International Aid Transparency Initiative.

Figure 8 was updated on 24 November 2020.

Downloads

Notes

-

1

Development Initiatives, 2020. Adapting aid to end poverty: Delivering the commitment to leave no one behind in the context of Covid-19. Available at: /resources/adapting-aid-to-end-povertyReturn to source text

-

2

IATI is a global initiative to improve the transparency of development and humanitarian resources and their results to address poverty and crises. More information is available at: https://iatistandard.org/en/ .Return to source text

-

3

Amounts the donor is contracted to disburse.Return to source text

-

4

Actual spend in fulfilment of a contract.Return to source text

-

5

Data is published on donors’ own websites.Return to source text

Related content

Adapting aid to end poverty: Delivering the commitment to leave no one behind in the context of Covid-19

This report calls for us to refocus ODA (aid) in the context of Covid-19, shifting the ‘leave no one behind’ agenda from inclusive growth to inclusive recovery. It analyses changes to poverty and how the pandemic has impacted finance vital to the poorest people.

How is Covid impacting people living in poverty worldwide?

Use interactive charts and analysis of key trends to explore how the Covid-19 pandemic is affecting people living in poverty at the global, regional and national levels, as well as inequality within countries. What makes certain groups vulnerable to its impacts?

How is aid being impacted by Covid-19, and why is it so hard to find out?

In this podcast DI's Anna Hope, Bill Anderson and Amy Dodd discuss how aid is being impacted by Covid-19, and the opportunities and challenges to tracking changes in development finance in real time.