Investments to end poverty 2018: Chapter 3

Mobilising all resources to leave no one behind

DownloadsKey messages

- All actors will benefit from achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and have a responsibility to contribute towards them.

- Investing to end poverty and close the gap between the poorest people and places and the rest is not just about scaling up total resources, but also the right types of finance for the right interventions. Increasing one type of finance will not automatically substitute the need for another.

-

International financing often bypasses countries that need it most – those with the lowest domestic capacity and highest levels of poverty:

- Countries where over a fifth of people live in extreme poverty receive a quarter of the volumes of international financing per capita (excluding official development assistance (ODA)), compared with countries where less than 5% of people do.

- Countries where per capita government revenue is less than $400 receive less than a sixth of the levels of non-ODA financing per capita compared with countries where government revenue levels are above $4,000 per capita.

- Countries at most risk of being left behind receive a quarter of the flows per capita going to other developing countries (excluding ODA).

- The private sector will be key, but poor people cannot wait for international commercial investments – currently concentrated in countries with low risk and healthy business environments – to shift towards them. International financial and development finance institutions providing blended finance and de-risking are equally constrained from working in the poorest and most vulnerable places and will need changes to mandates to start mobilising resources to where they are needed most.

- Beyond volumes, identifying synergies between types of finance, by knowing what resources are available and how they are being used, can maximise impact and free up scarce ODA.

- National public finance and ODA will continue to be central to investments directly focused on strengthening human capital development, which are being left behind by other forms of finance.

- Comparable subnational data across resources is limited but shows the gap in access to resources between the poorest people and other at the local level. Better production, availability and use of local data can help guide where different resources are needed most.

All resources have a role to play in, and a responsibility to contribute to, leaving no one behind

ODA, while critical in its ability to target poverty directly, will not be enough to meet the ambitions of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (Agenda 2030); it is far from the largest resource flow available and arguably not the most important. Nor will the economic growth that resulted in achieving Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 1 early be sufficient if poverty is to be ended and inequality reduced.

In the SDG era, all resources – public, private, local, national and international – have a role. They also have a responsibility to contribute to the universal goals. The gains made by achieving them will be felt by all, rich and poor, individual, household, corporation and government. Shared benefits mean shared ownership of shared objectives – and shared responsibilities.

But it is not just about numbers – it is more than a question of scaling up total financing. Simply increasing investments in developing countries will not result in the progress needed to achieve the twin SDGs 1 and 10, nor the other SDGs addressing human capital, infrastructure, security and the environment on which these two depend. The quality of investments, backed up by political will driving the right choices, will also matter: the types and sources of financing being used, the areas where they are being invested and the people who are benefiting. While more financing is needed, it has to be the right type.

This means it cannot be assumed that increasing one type of resource will be an automatic substitute for another. ‘Billions to trillions’ may be misleading for the potential scale of some of the resources available to the poorest people and countries, but so is its suggestion that the end of poverty lies in achieving a single aggregate monetary sum.

Looking beyond numbers means looking at the efficiencies and additional impact to be gained from different types of finance, and the actors that control them, working together, either within a defined framework of sequencing or layering, or a more loosely defined approach grounded in clear awareness of what other resources there are and what they are doing.

Within a burgeoning range of often interconnected sources, types, and modalities of funding and finance, each with their own sets of objectives, incentives and comparative advantages, strengthening their complementarity and building synergies will be as important as overall volumes. [1] To do this, the landscape of available resources and how they are used needs to be understood. Donors and governments need to know where their scarce concessional finance can make the most difference in the absence of other sources of investment. And other diverse actors need to know where opportunities are that both meet their own objectives and build momentum towards the SDGs. Having a clear picture of the overall landscape, including what type and scale of financing is being invested where, on what and at whose benefit, is thus a crucial step to more effective and impactful investments to end poverty. [2]

Globally, domestic resources and commercial financing are the most significant sources of investment

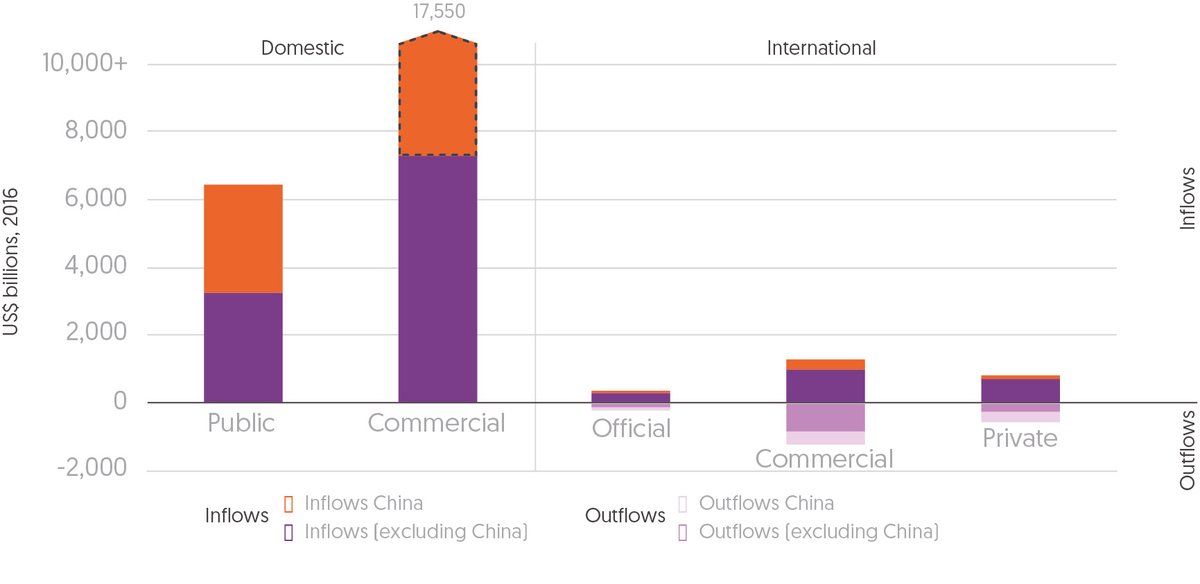

Domestic resources are the primary source of finance in developing countries and will be the key driver in country-level investments to end poverty. In 2016, domestic public resources controlled by developing countries (estimated by non-grant government revenue) totalled US$6.4 trillion, almost 20 times the US$0.3 trillion of international official financing flowing to these countries. Similar scales of magnitude differentiate domestic commercial resources (US$24.9 trillion) from international commercial inflows (US$1.3 trillion) in these countries (Figure 3.1). China accounts for the vast majority of this difference, but even when excluding China the differences are impressive, with domestic public resources accounting for over nine times the volume of international official financing, and domestic commercial resources (estimated by domestic credit to the private sector) accounting for over seven times the volume of international commercial inflows to developing countries. Combined, these domestic resources are 12 times those of international flows to developing countries.

Figure 3.1 Domestic resources in developing countries are 12 times larger than international finance flows to developing countries, of which commercial sources of finance dominate

Domestic resources in developing countries are 12 times larger than international finance flows to developing countries, of which commercial sources of finance dominate

Source: Development Initiatives based on International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, UN Conference on Trade and Development, OECD DAC and national sources.

Note: Data is for the most recent available year across all categories; this is 2016, except for private finance mobilised via blending (included in international commercial estimates) and private development assistance (included in international private estimates)

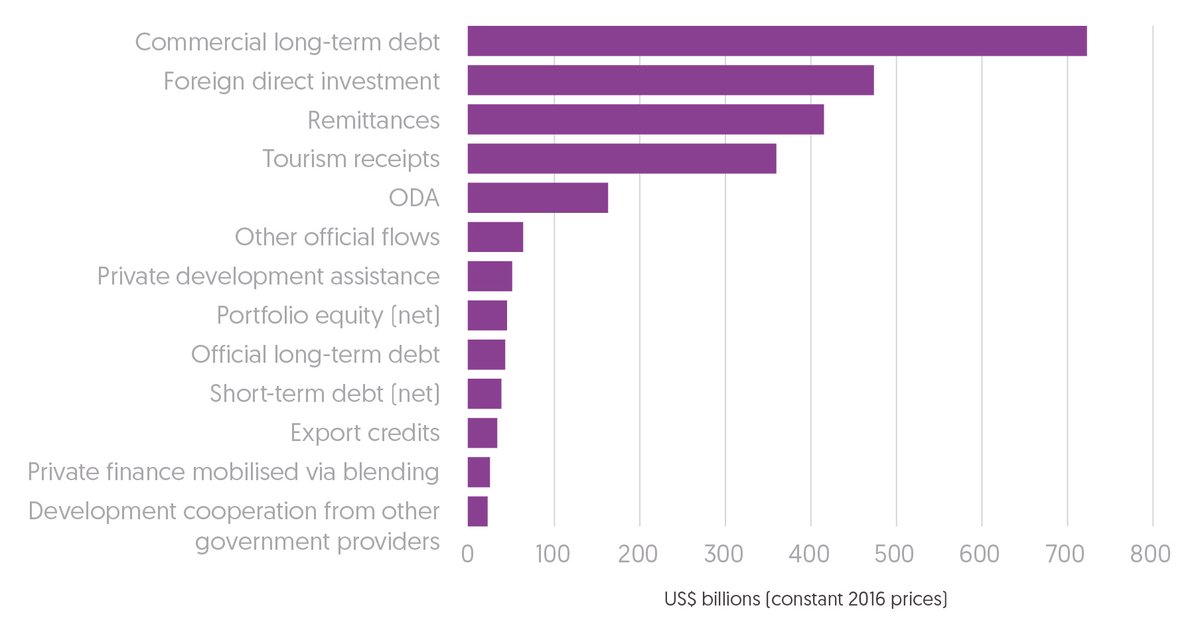

Commercial resources are the largest category of financing in both domestic and international investments and flows (Figure 3.1). Beyond the aggregate level, the two main components of international commercial financing – commercial long-term debt and foreign direct investment (FDI) – are the two largest sources of international financing to developing countries as a whole, at US$723 billion and US$476 billion respectively (2016), equivalent to 4.3 times and 2.9 times ODA (Figure 3.2).

Notably, large proportions of international commercial resources ultimately flow out of developing countries. In 2016, commercial outflows from developing countries totalled US$1.19 trillion, equivalent to 90% of inflows (Figure 3.2). Of this, US$254 billion were outward FDI investments – more than half of the volume of FDI inflows. The remainder, US$935 billion (equivalent to 79% of the total) comprised interest and capital repayments on loans as well as outflows of profits on FDI.

Figure 3.2 Commercial long-term debt and FDI are the two largest sources of international financing to developing countries

Commercial long-term debt and FDI are the two largest sources of international financing to developing countries

Source: Development Initiatives based on World Bank, UN Conference on Trade and Development, OECD DAC and national sources.

Notes: FDI: foreign direct investment. Data is for 2016, except for private finance mobilised via blending and private development assistance. Development cooperation from other government providers includes data on disbursements of development cooperation from non-DAC members that report to the OECD DAC as well as data on disbursements of development cooperation from other government providers that do not report to the OECD DAC and for which data was compiled from national sources.

Growth in domestic public resources is slowing: some countries could increase levels further but many will still fall short of requirements

Domestic public resources are by far the largest development finance flow that can be invested directly in reducing poverty and be redistributive in nature through, for example, investments in social protection, health and education. Domestic public resources are managed by governments who hold ownership over national development agendas. They are responsible for aligning their expenditure with domestic development priorities and can strengthen accountability between decision-makers and the people that development efforts are supposed to serve.

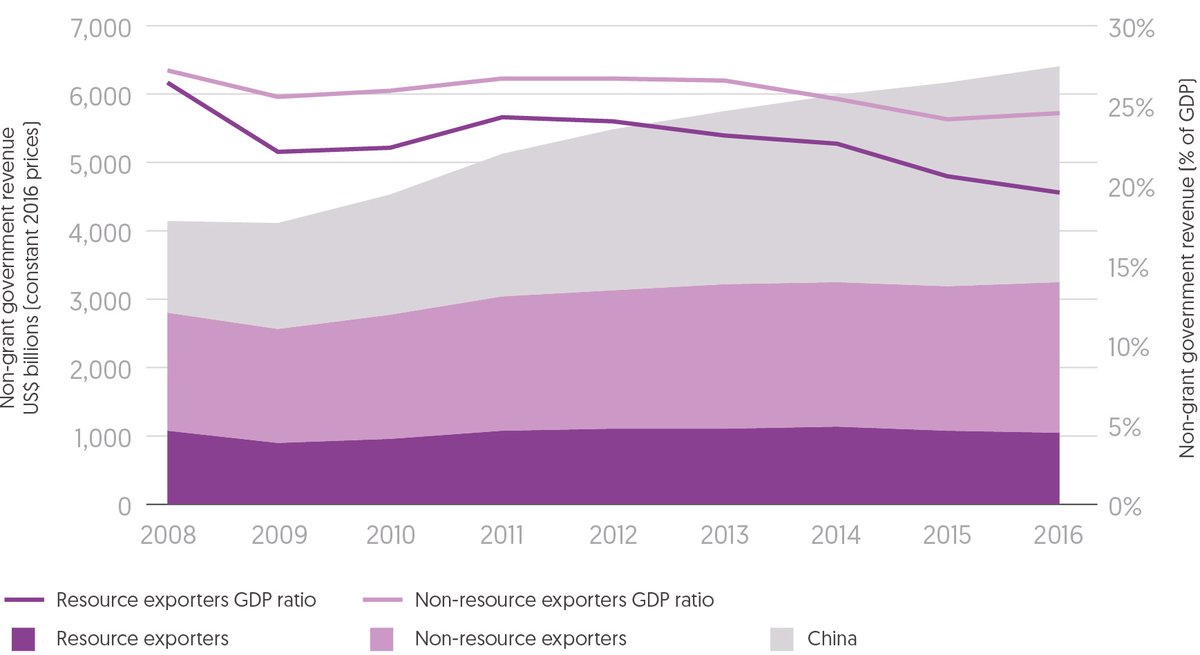

Growth in domestic public resources is slowing across developing countries

Aggregate domestic public resources (measured by non-grant government revenue) have grown from 2008 levels of US$4.1 trillion to US$6.4 trillion in 2016. Growth, however, has not been equally distributed across countries. While China's non-grant government revenues more than doubled since 2008, other developing countries saw more moderate growth (non-resource exporters) or a marginal decline (resource exporters) (Figure 3.3). Growth has almost halved since 2012 compared with the previous five years (from an average annual growth rate of 7.3% between 2008 and 2012, to 4.0% between 2012 and 2016). Meanwhile it has not kept pace with economic growth – government revenue as a share of GDP has fallen across developing countries (excluding China) since 2011, while levels in advanced economies have remained relatively constant in aggregate. [3]

Figure 3.3 In aggregate, domestic public resources have increased by 55% since 2008 but growth has slowed

In aggregate, domestic public resources have increased by 55% since 2008 but growth has slowed

Source: Development Initiatives based on IMF World Economic Outlook database, April 2018 and IMF Article IV Staff and programme review reports (various).

Note: Countries whose government revenue data is not available for entire span of 2008–2016 are not included.

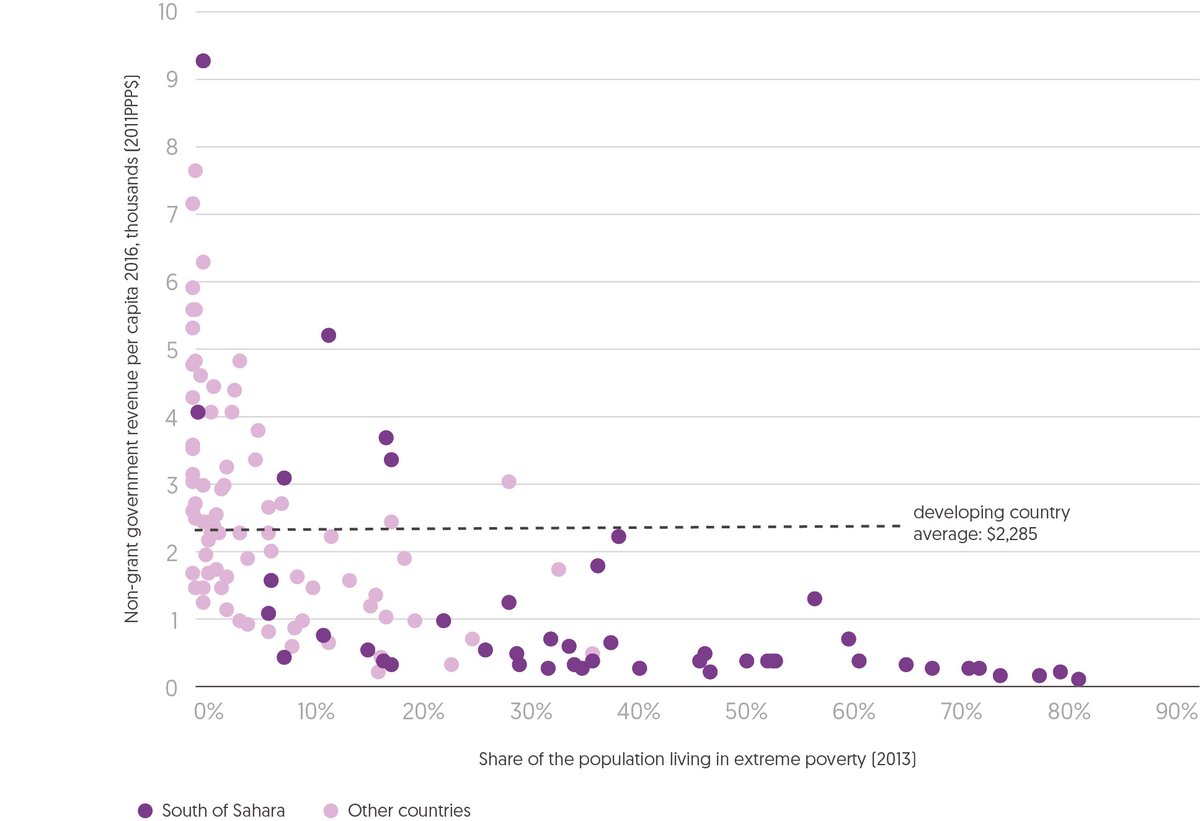

Domestic public resources are lowest where poverty is highest and is projected to be highest by 2030

Absolute volumes of domestic public resources are also lowest where poverty is highest. In sub-Saharan African countries, where over a fifth of the population lives in extreme poverty, levels of per capita government revenue are below – and in many cases, far below – the $2,285 per capita developing country average (Figure 3.14). And the countries identified as most at risk of being left behind – where approximately 80% of poor people globally are projected to live by 2030 – are also among those with the lowest levels of domestic public resources globally. Achieving SDG1 will require progress at the individual level, but the countries needing to make the most progress are those with the least per capita resources.

Figure 3.4 Domestic public resources are lowest where extreme poverty is highest

Domestic public resources are lowest where extreme poverty is highest

Source: Development Initiatives based on World Bank PovcalNet, and IMF World Economic Outlook database and IMF Article IV Staff and programme review reports (various).

Notes: Countries for which no poverty data or government revenue per person data is available have been excluded. Extreme poverty is defined by the $1.90 a day international poverty line (2011 PPP$: purchasing power parity).

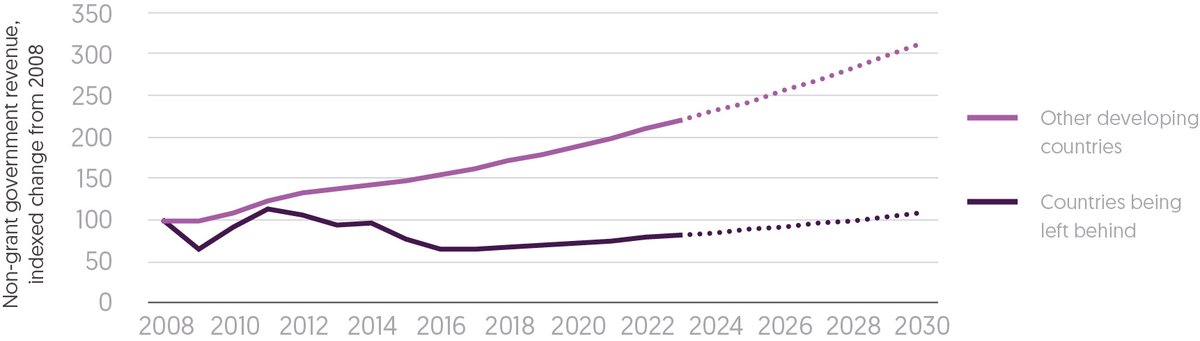

The gap in domestic public resources between these countries and others will also widen

While the countries where most progress is needed to achieve SDG1 have low levels of revenue now, projections suggest that the gap in revenue levels between these and the rest is going to increase between now and 2030. Growth rates for high poverty countries will be only marginally higher than others, and low baselines mean wealthier countries are pulling further away.

Domestic public resources in countries where over 20% of the population live in extreme poverty are projected to grow faster, in aggregate, between 2019 and 2030 (5.2% a year) than those in countries where less than 5% of people are extremely poor (on average 4.9% a year), assuming medium-term forecasts continue through to 2030. [4] Similarly, domestic public resources in countries where current per capita levels are extremely low (below $400) are projected to grow faster than those in countries where they are above $4,000 (5.7% compared with 4.9%). However, just as Chapter 1 shows a growing gap between the poorest 20% of people and others, so the lower revenue baselines mean the gap between the poorest and richest countries is going to widen.

Notably, in countries at risk of being left behind, domestic public resources are actually projected to grow more slowly than in other developing countries, meaning that if no action is taken the gap between these and other countries can only widen (Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5 Countries being left behind will see slower growth in domestic public resources than other developing countries

Countries being left behind will see slower growth in domestic public resources than other developing countries

Source: Development Initiatives based on IMF World Economic Outlook database, April 2018 and IMF Article IV Staff and programme review reports (various).

Notes: Chart is indexed from 2008 showing levels of change in non-grant government revenue for countries being left behind and other developing countries. Projections assume a constant government revenue-to-GDP ratio. Real GDP growth is available at the source until 2023; growth for 2024-2030 is set equal to 2023 at the country level.

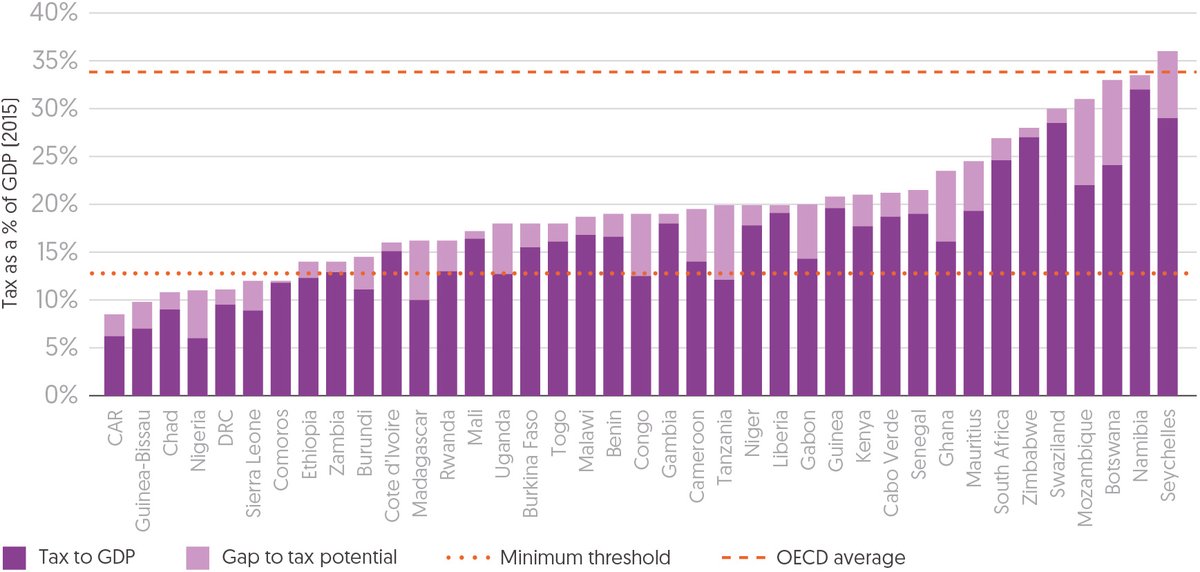

But domestic revenue mobilisation could be increased, even in some of the poorest countries, and donors can play a key role in supporting the right efforts

Beyond the aggregate level, the picture is less stark. While not equal across all countries, there is potential to increase government revenue – estimated by the ‘tax potential’, the level of tax revenue a country can achieve by maximising its tax effort, subject to economic and structural constraints. The overall tax potential across developing countries is substantial, estimated at around US$2 trillion, although low income countries account for just 1% (US$15bn). [5] Sub-Saharan African countries vary considerably in the scale of the ‘tax potential’ or ‘tax gap’ (i.e. the difference between current and potential tax collection capacity) (Figure 3.6). Donors can work to assist governments in filling these tax gaps or expanding their potential, depending on the particular challenges faced.

Figure 3.6 In many sub-Saharan African countries there is potential to grow the tax base, but also a need to increase tax potential

In many sub-Saharan African countries there is potential to grow the tax base, but also a need to increase tax potential

Source: Development Initiatives based on IMF and OECD.

Notes: CAR: Central African Republic. The 12.88% minimum threshold refers to the tax-to-GDP ratio to enable the state to perform some of its most important government functions, especially adequate spending on developmental programmes.

These challenges can be grouped into two distinct areas: challenges collecting revenues and weak enabling environments. The former refers to challenges faced by governments due to resource or capacity constraints, low levels of taxpayer compliance and tax abuses by multinational corporations practising aggressive tax planning strategies to lower tax burdens in developing countries and exploit weak administrations (see Box 3.1). The latter refers to challenges related to areas such as economic growth and structure (e.g. informal, formal and subsistence labour markets), trust in government to improve compliance (e.g. perception, rule of law, transparency and accountability) and other underlying factors such as security and stability, and broader political and power dynamics that may steer governments away from implementing pro-poor tax reforms.

Box 3.1

The impact of multinational tax avoidance on leaving no one behind

There is an ongoing debate about whether the definition of illicit financing flows should be widened beyond ‘dirty money’ to include financial flows associated with multinational tax avoidance (or profit shifting), which can be legal. [6] While it is beyond the scope of this report to participate in this debate, the detrimental impact that multinational tax avoidance has on governments’ ability to mobilise resources at the domestic level is important to highlight. While estimates of the volume of revenues lost to profit shifting are lower than ODA in countries that receive substantial aid levels (such as Nigeria and Bangladesh), evidence suggests that on average, lower income countries lose more corporate tax revenue as a proportion of their GDP than higher income countries do. [7] Against the backdrop of Agenda 2030 and the commitment that actors across the globe and across industries have made to leave no one behind, this calls for urgent action to address international tax loopholes on the one hand and to strengthen capacity of tax administrations on the other to reduce the extent of exploitation by multinational corporations, especially in the poorest countries and those most at risk of being left behind. [8]

These barriers determine whether efforts to most effectively strengthen revenue mobilisation should focus on building government capacity, the wider enabling environment or a combination of the two. For example, in countries such as Tanzania and Congo where current tax-to-GDP ratios are just below the minimum threshold identified by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as adequate for providing basic services, [9] and where current capacity to collect taxes is lower than estimated potential capacity, efforts to support governments in overcoming challenges related to tax collection may be sufficient. In other countries, such as Liberia, Côte d’Ivoire and Comoros, where the tax gap is very small or close to zero, and where tax-to-GDP levels are very close or above the minimum threshold, enabling environment interventions will be key. Finally, in countries such as Chad, Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where even by closing the tax gap government revenue levels would still be below the minimum threshold, raising sufficient domestic public resources will require efforts to both strengthen governments’ revenue collection capacity as well as the broader enabling environment.

Domestic commercial resources can be a key source of financing to end poverty and there is scope to strengthen their potential

Domestic commercial resources are key to driving local and national economic growth. But with the right incentives and enabling environment they can also drive social and environmental progress through, for example, job creation and innovation. [10] Also, taxes paid by commercial entities operating in the country are an important source of government revenue, which can in turn be used towards national development priorities. Domestic commercial actors are therefore key partners in the quest to achieve the SDGs and ensure no one is left behind.

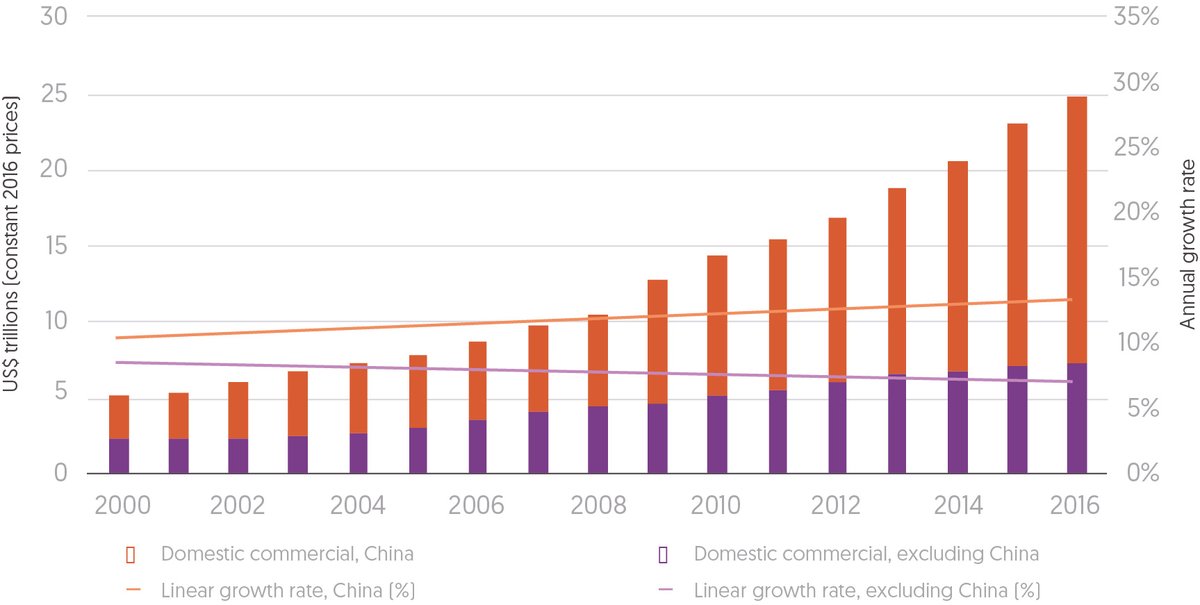

Growth in domestic commercial investment has been slowing in developing countries (except China) and remains concentrated in a handful of them

However, excluding China, growth in domestic commercial resources (estimated by domestic credit to the private sector) has been slowing down (Figure 3.7). Excluding China’s near-six-fold growth from US$2.94 trillion to US$17.5 trillion between 2000 and 2016, commercial resources in developing countries tripled to an aggregate US$7.3 trillion. Meanwhile annual growth rates decreased from an average of 9% between 2000 and 2007 to an average of 7% since 2008.

Figure 3.7 Since 2000, domestic commercial resources have grown substantially but, excluding China, growth has been slowing down

Since 2000, domestic commercial resources have grown substantially but, excluding China, growth has been slowing down

Source: Development Initiatives based on World Bank data.

Note: Domestic commercial refers to domestic credit to the private sector.

Importantly, this type of financing also remains concentrated in a few countries. Only a handful account for most of the growth in domestic commercial resources outside China: India, Brazil, Turkey, Thailand and South Africa (all middle income countries (MICs)).

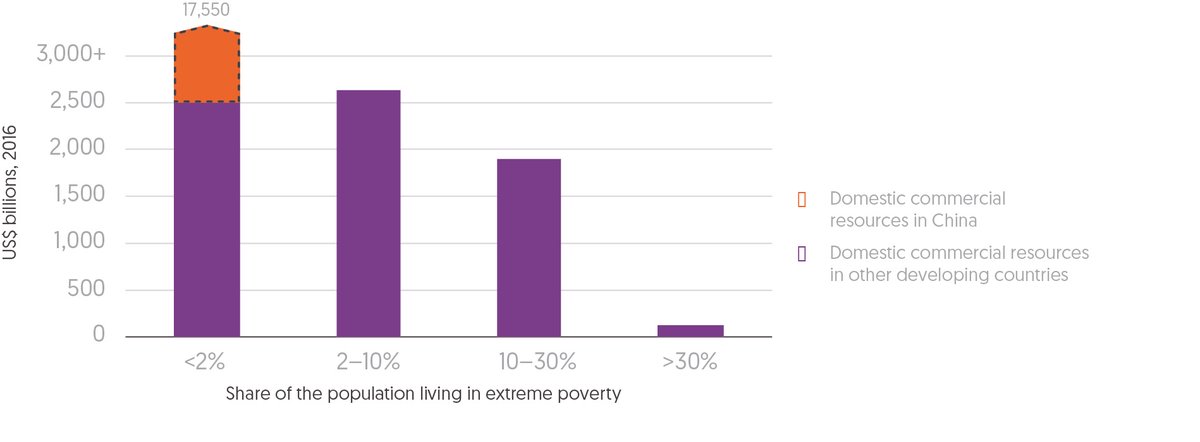

Countries where poverty is highest and those being left behind have the least domestic commercial resources

In contrast, many countries, particularly those with high poverty rates, continue to lag behind on domestic commercial investments. Based on latest available data (from 2016), countries where extreme poverty is highest have the least domestic commercial resources (Figure 3.8). The majority (70%) of developing countries’ domestic commercial resources are in China, where less than 2% of people live in extreme poverty. When China is excluded, 37% of these resources are in the 26 countries where between 2% and 10% of people live in extreme poverty, and another 35% in the 29 countries where less than 2% of people do. In contrast, the 28 countries where more than 30% of people live in extreme poverty account for just 2% of developing countries’ domestic commercial resources. Also, as a share of GDP, domestic commercial resources remain less significant in countries where poverty is highest – accounting on average for 18% of GDP in countries where over 30% of people live in extreme poverty, compared with 140% in countries where less than 2% of people do.

Figure 3.8 Domestic commercial resources are lowest where poverty is highest

Domestic commercial resources are lowest where poverty is highest

Source: Development Initiatives based on World Bank data, including World Development Indicators and PovcalNet.

Notes: Countries for which no poverty data is available have been excluded. Extreme poverty defined by the $1.90-a-day international poverty line. Bands were identified to contain as-even-as-possible numbers of countries

Similarly, in countries where poverty is projected to be highest and which are at risk of being left behind, the significance of domestic commercial resources continues to be lower than elsewhere – as a percentage of GDP they account, on average, for around a quarter of the levels found in other developing countries excluding China. Between 2000 and 2016, they accounted for just 12.5% of GDP in countries being left behind. This is despite relatively rapid growth in recent years in several of the countries being left behind, which are also resource exporters (e.g. Congo, South Sudan, Chad and DRC).

With the right investments there is scope to strengthen the private sector in many of the poorest countries. Domestic commercial financing can play an important role in driving the ‘right kind of growth’, particularly in light of the attention paid in international development discourse to mobilising international commercial finance in developing countries (e.g. through blended finance). [11] Just as foreign commercial investments can contribute to growth and poverty reduction, so domestic commercial actors can drive economic and social progress through the sectors in which they operate.

Beyond emphasising blending and international private capital, donors can support governments to scale up the mobilisation of domestic commercial resources through private sector development interventions aimed at strengthening the broader enabling environment. They can also do so by directly supporting domestic enterprises, with the ultimate aim of assisting countries in putting the structures and incentives in place to encourage sustainable and inclusive growth strategies. [12] In many countries at risk of being left behind where the private sector is underdeveloped, such interventions may yield more sustainable returns and create the conditions for a more vibrant domestic private sector than crowding in increased international private capital investments.

What domestic commercial investments are made, and where, are difficult to assess, but emerging initiatives show encouraging SDG trends

Given the lack of international, comparable, disaggregated data on domestic commercial resources, it is difficult to assess what this type of financing is being spent on and invested in. Yet initiatives are emerging to monitor the contributions of domestic businesses to the SDGs. And the signs are encouraging.

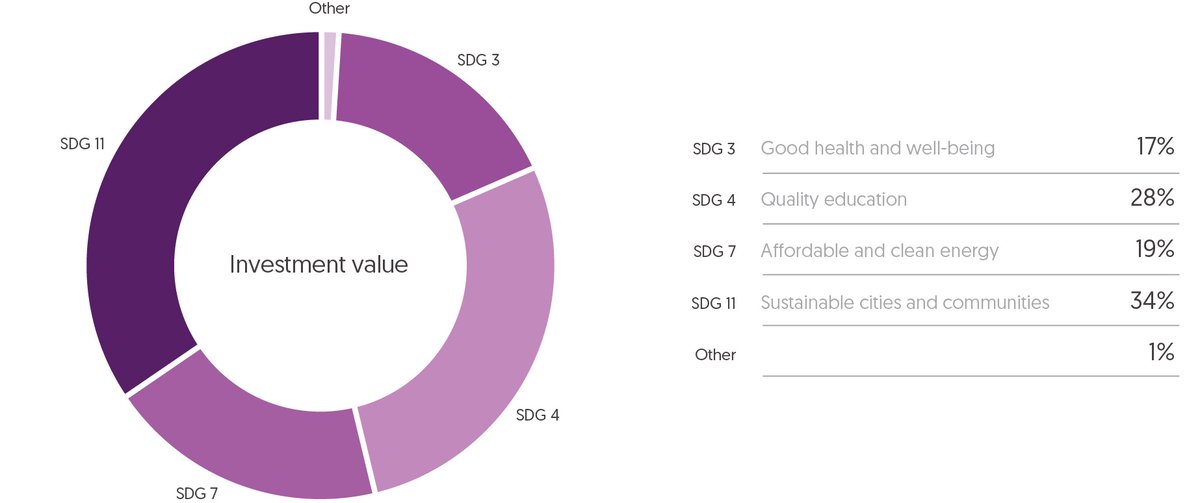

In the Philippines, for example, the UN Development Programme and the Philippine Business for the Environment brought together evidence on the Filipino business community’s contribution to the SDGs and published findings from research and voluntary reporting from 75 companies in 2017. Key contributions were to sustainable cities (SDG11) and responsible consumption and production (SDG12), while significant investments were also made in the human capital-focused SDGs 3 and 4 (Figure 3.9). Initiatives supporting SDG3 were largely focused on ensuring accessibility and affordability of healthcare services, including through mobile technology. The largest proportion of SDG4-aligned investment went toward student scholarships and lending to employees who have insufficient resources to send their children to school. [13]

Figure 3.9 Most Filipino business investments targeted SDGs 11 (34%) and 4 (28%)

Most Filipino business investments targeted SDGs 11 (34%) and 4 (28%)

Source: Development Initiatives based on UN Development Programme and Philippine Business for the Environment data.

Notes: No investments were recorded for SDGs 9, 10, 16 and 17. Total does not add up to 100% due to rounding.

As well as changes in businesses’ own strategies and operations, there are increasing capital market-related initiatives that aim to promote more sustainable behaviour by domestic commercial actors and investors. [14] For example, the Stock Exchange in Thailand has encouraged firms to establish sustainability reporting practices and provides training to support these efforts. [15] And the Jakarta Stock Exchange in Indonesia has implemented the Sri Kehati Index which values listed firms against factors related to sustainability and responsible investment including environment, community, corporate governance, human rights, business behaviour and labour practice and decent work. [16]

International financing can complement domestic resources, but volumes are lowest in the the places and sectors where progress needs to be fastest

International forms of financing – official, commercial and private – can complement domestic sources in supporting countries achieve national development goals and end poverty. However, different flows have different objectives and comparative advantages, meaning that they cannot always substitute one another’s role in the overall financing mix. And while other forms of international financing have been increasing overall in recent years, ODA will continue to be crucial in supporting the poorest countries and the sectors being bypassed by such financing, not least because of the timelines that must be acted on to ensure no one is left behind by 2030.

International financing has risen across all categories, some more than others

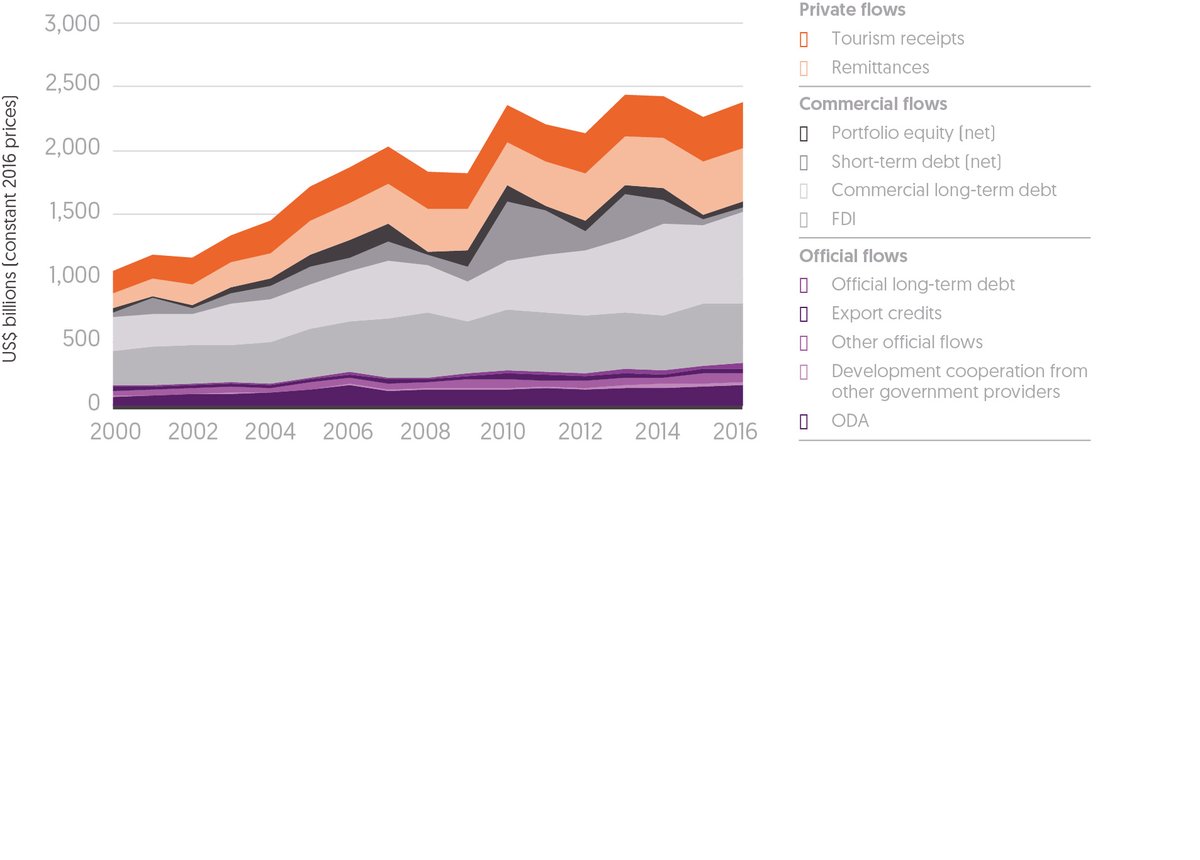

International resource flows to developing countries have more than doubled since 2000 to almost US$2.4 trillion, with all types of financing increasing – though some faster than others. Private resources – including remittances and receipts from international tourism [17] – have seen the greatest growth rates (more than 150%), from US$302 billion in 2000 to US$779 billion in 2016. Commercial flows – including FDI, commercial lending (both long- and short-term) and portfolio equity investments – grew more than two-fold from US$605 billion to US$1.3 trillion, though they are more volatile than other types of finance. Official financing – including both concessional and non-concessional flows from public actors – has grown at a slower rate and accounts for lower volumes than others, increasing from US$168 billion in 2000 to US$338 billion in 2016 (Figure 3.10).

Figure 3.10 In aggregate, all international financing flows have been increasing with private flows increasing the fastest overall

In aggregate, all international financing flows have been increasing with private flows increasing the fastest overall

Source: Development Initiatives based on World Bank, UN Conference on Trade and Development, OECD DAC and national sources.

Notes: Flows for which historical data is not available are excluded; these include private finance mobilised via blending and private development assistance. Development cooperation from other government providers includes data on disbursements of development cooperation from non-DAC members that report to the OECD DAC as well as data on disbursements of development cooperation from other government providers that do not report to the OECD DAC and for which data was compiled from national sources.

But countries with high poverty and low revenues still have least access to international financing

The trends and distribution of different forms of international financing vary when looking at individual countries but two trends are clear: some flows are highly concentrated in a limited number of countries and most bypass the countries where extreme poverty is highest and domestic resources are lowest.

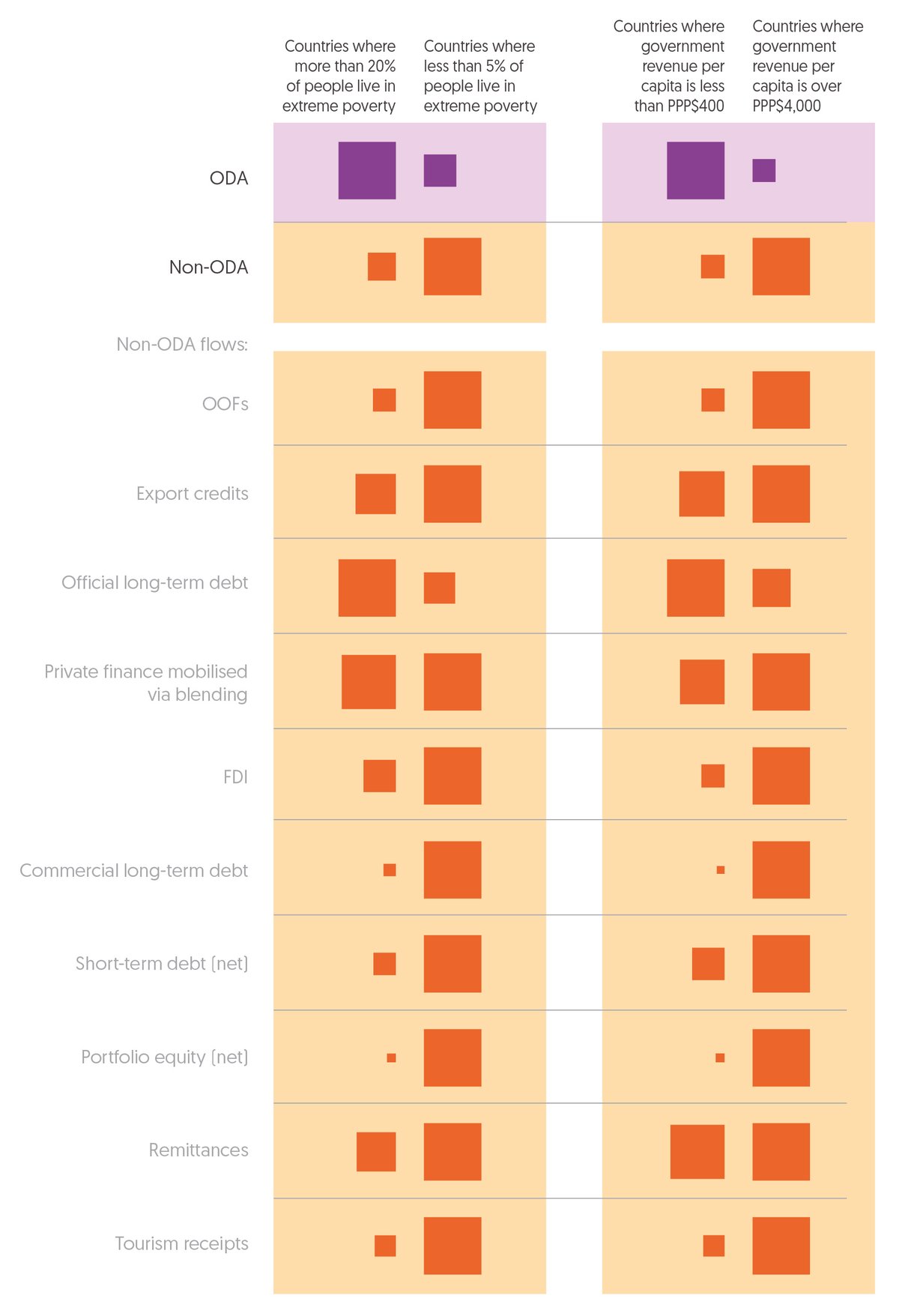

In 2016, per capita non-ODA financing in countries where over 20% of the population live in extreme poverty amounted to US$138, less than a quarter of the US$577 in countries where the proportion of extremely poor people was less than 5%. Similarly, countries with per capita government revenue levels below $400 received less than a fifth (US$97) of the US$559 received by countries with over $4,000 in per capita government revenue. Except for ODA and official long-term debt, these differences are reflected across all flows (Figure 3.11).

Figure 3.11 Non-ODA flows are far smaller where poverty is greatest and where domestic public resources are lowest

Non-ODA flows are far smaller where poverty is greatest and where domestic public resources are lowest

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD DAC, UN Conference on Trade and Development IMF and World Bank data.

Notes: OOFs: other official flows. Flows for which recipient-level disaggregation is not available are excluded. Scaled shapes represent per capita volumes of each type of finance flowing into the country groupings identified in the column headings.

Beyond ODA, countries at most risk of being left behind receive particularly low levels of international financing compared with other developing countries

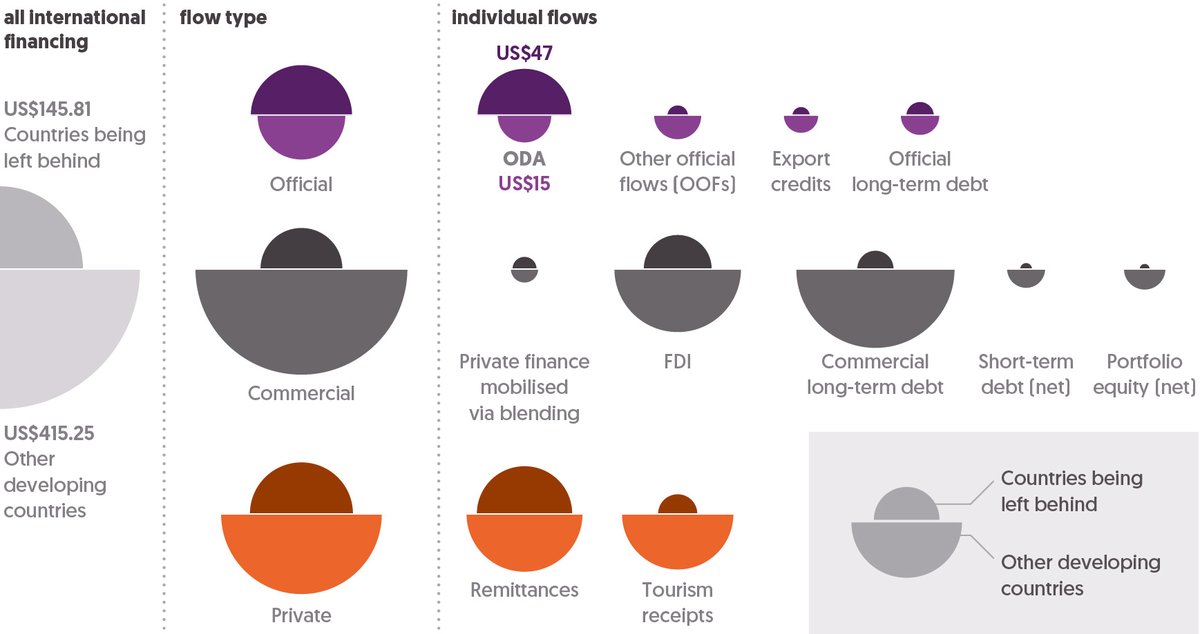

As well as countries with high poverty and low revenues, international financing is bypassing those that need to be making the greatest progress to achieve the SDGs. Countries identified as most at risk of being left behind are among the smallest recipients of such flows (except ODA). Figure 3.12 illustrates the gap between these and other countries. In 2016, the countries being left behind received on average US$146 per capita in total international financing, compared with US$415 in other developing countries, and the gap is visible across all flows except ODA.

Figure 3.12 Excluding ODA, countries most at risk of being left behind receive the least international financing

Excluding ODA, countries most at risk of being left behind receive the least international financing

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD DAC, UN Conference on Trade and Development and World Bank data.

Notes: Flows for which recipient-level disaggregation is not available are excluded. Data is all for 2016, except for private finance mobilised via blending which is for 2015 (latest year available). Flows for which recipient level data is not available are excluded from this analysis.

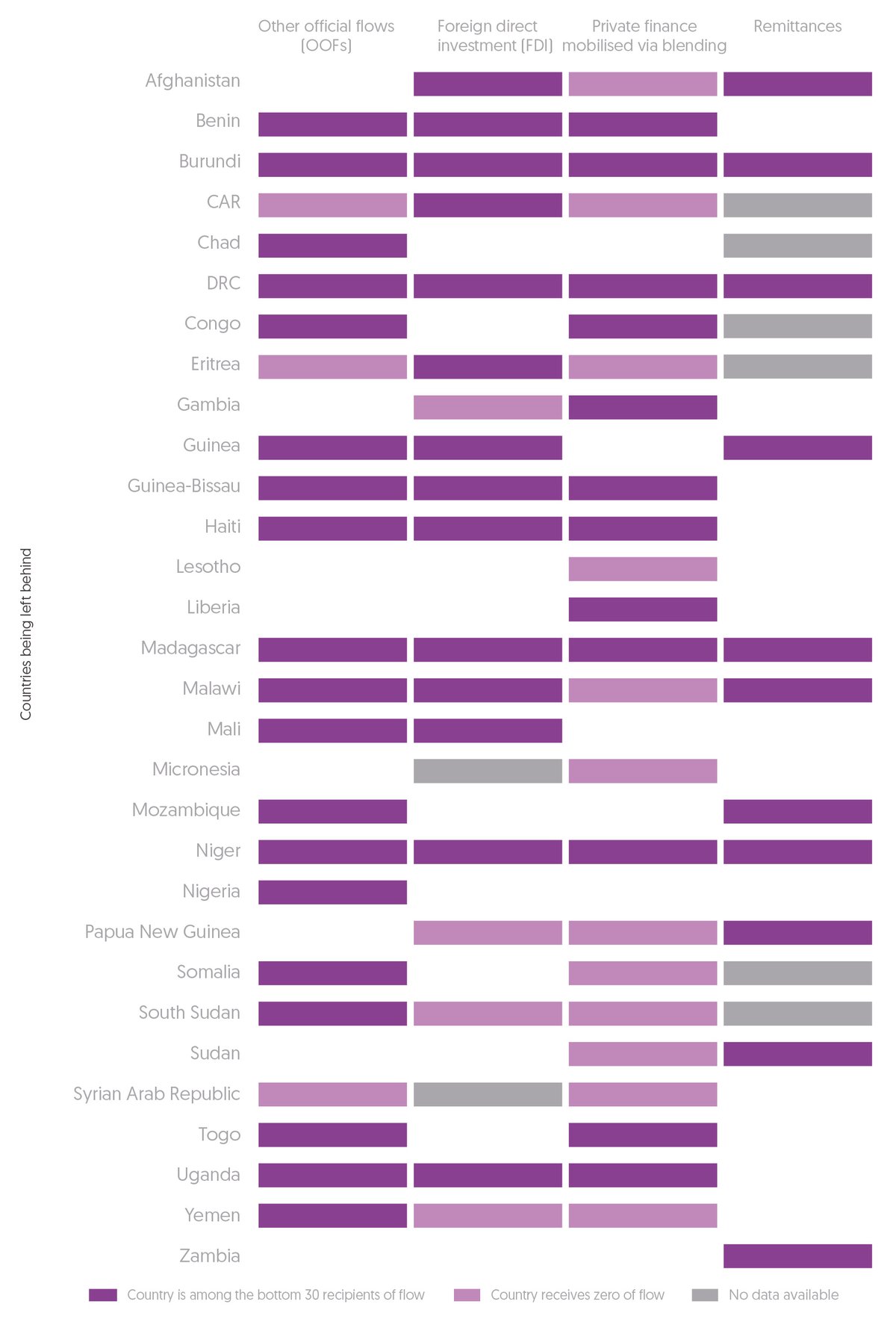

This is further illustrated in Table 3.1, which shows that most countries at risk of being left behind (for which data is available) are among the smallest recipients of other official flows (OOFs), private finance mobilised via blending, FDI and remittances and are often low recipients across multiple flows.

Table 3.1 Countries being left behind are among the smallest recipients of OOFs, FDI, private finance mobilised via blending and remittances

Countries being left behind are among the smallest recipients of OOFs, FDI, private finance mobilised via blending and remittances

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD DAC, UN Conference on Trade and Development and World Bank data.

Notes: CAR: Central African Republic. Countries are established as among the 30 smallest recipients of each flow using US$ per capita figures. Countries receiving zero for a flow are indicated as such from the source, this includes negative values set to zero for FDI.

Growth in non-concessional official finance is resulting in debt servicing levels that are rising faster in the countries that can afford it least

Non-concessional official flows (comprising OOFs, export credits and official long-term debt) can be an important source of additional finance, particularly in productive sectors that generate returns, such as infrastructure projects. Yet the supply of such financing (particularly non-concessional official loans) must be considered first and foremost against the use and terms of the investments – although this remains difficult to do in the absence of disaggregated data on what this type of financing is being spent on. It should also be considered against the scale and scope of investments that would be foregone as a result of having to service increasing debt (e.g. growing interest payments squeezing government spending in sectors such as health and education).

A more-than six-fold growth in non-concessional official financing to sub-Saharan and North African countries between 2000 and 2016 is a key regional trend of such financing over the last one-and-a-half decades – particularly when compared with a more modest doubling of concessional ODA in sub-Saharan Africa and the 25% growth in aid to North Africa over the same period. While North Africa saw substantial growth across all non-concessional flows, in sub-Saharan Africa the trend is mainly attributable to a nearly thirteen-fold increase in nonconcessional lending by official creditors that is not reported as OOFs (i.e. official long-term debt) led by Angola, Ethiopia, Senegal and Djibouti.

Given the potential contribution of this type of financing to development outcomes, such growth need not, necessarily, be concerning. However, the rising outflows that this type of financing creates, through interest and capital repayments, is a concern to be monitored, particularly given growth is currently faster in the countries identified as being at risk of being left behind, including countries already identified as being at risk of debt distress (e.g. DRC) or already in debt distress (e.g. Mozambique). [18]

Box 3.2

Building synergies between flows requires better data: Security and development spending

A new mindset that looks beyond traditional development programming is needed if growth and progress in people’s well-being is to be sustained; a mindset that recognises the importance of a broad and dynamic network of public global policies and goods – including development aid – from environmental and political security to communicable diseases and global counter-terrorism.

A safe, healthy place to live is central to everyone’s lives, including people living in extreme poverty. Instability, conflict and insecurity are key drivers of poverty and barriers to progress, and as numbers of displaced people reach record levels year on year and as poverty becomes increasingly concentrated in fragile contexts, so a wider scrutiny of the full range of resources available to address these challenges, alongside a better understanding of how they are used, will be an essential baseline to drive synergies between different types of flows and expenditures. Strengthening synergies will be as important as scaling up and targeting resources.

Some aid serves security and peacekeeping objectives (see Chapter 2), but such flows are insignificant against the estimated US$1.7 trillion global military and security expenditures each year. Such spending has grown only marginally over the last decade, driven by a slow but steady growth in developing countries, which now account for 29% of expenditures. Spending in developed countries fell 5% over the decade after peaking in 2010. Total peacekeeping operations in developing countries – both bilateral and through multilateral operations with a mandate from the UN security council or the country government in which operations take place – have fluctuated between US$8 billion and US$10 billion since 2008. However single major operations such as in Afghanistan and Iraq have intermittently pushed totals significantly higher, such as the US$212 billion spent in 2011.

Developing comparable data on how much is being spent by any government in any particular developing country – including apportioning of grants and official lending for military capital and services to certain places across a broad range of activities – is a substantial task yet to be undertaken. Yet such spending could profoundly impact people in poverty. Having a baseline of what is being spent where will be one step towards identifying the synergies needed to harness this potential.

International commercial resources are growing but lagging behind commitments to increase spending in the poorest and left behind countries

International commercial flows can complement domestic commercial investments and, if appropriately directed, be important drivers of economic development and inclusive growth. However, to maximise their contribution to national development goals and to reducing poverty more broadly, they must also complement public efforts through, for example, supporting domestic revenue mobilisation by paying tax in the country of operation, adhering to environmental and social standards in their operations, and ultimately embracing the SDGs as a core aspect of their business models (as some are already doing – see Box 3.5).

The Addis Ababa Action Agenda, which complements Agenda 2030 in particular in the area of financing, highlighted the need to expand international commercial financing, particularly FDI, to unfunded or underfunded places. [19]

Data shows these commitments are not being met. While international commercial finance to developing countries, including FDI, has increased in volume, it has actually been decreasing overall in countries identified at risk of being left behind. [20] This widening gap in commercial flows is also seen when expressed as a percentage of GDP. International commercial finance in these terms has been falling since the late 2000s across developing countries, but more steeply for countries being left behind – from 5.7% of GDP in 2007 to 2.9% in 2016, compared with 7.8% of GDP in 2007 to 5.2% in 2016 in other developing countries.

International private financing is concentrated in a few countries and has been falling as a share of GDP

International private finance – made up here of remittances and international tourism receipts – has an important role in complementing other types of finance. Remittances tend to be countercyclical and can provide vital sources of income to poor households in crisis or smooth consumption patterns. And a small-but-growing body of evidence suggests they can potentially contribute to development through, for example, local growth linkages. Instruments, such as diaspora bonds, seek to harness this potential further. International tourism – as highlighted in SDGs 8, 12 and 14 – can be a source of sustainable job creation and can promote local culture and products.

While significant overall, international private financing remains concentrated in a relatively small number of countries that either have large diasporas or are popular tourist destinations. In 2016, India and China accounted for 30% of all remittances to developing countries, while the five largest developing country recipients of international tourism spending – all (except India) with less than 5% of the population living in extreme poverty – accounted for 46% of the total. When compared with the overall size of the economy, international private financing remains higher in countries being left behind. But, similarly to commercial sources of finance, since the late 2000s it has been decreasing as a proportion of GDP faster in these countries compared with other developing countries – from 8.2% in 2009 to 5.0% in 2016 in countries being left behind. This compares with a more marginal drop from 3.4% in 2009 to 3.0% in 2016 in other developing countries. Thus while international private flows will bring substantial benefit to some developing countries, they cannot be expected to be a substitute for national or international public finance for a number of the poorest countries and those at most risk of being left behind.

Box 3.3

Philanthropic spending is growing but more data is needed to assess and exploit its synergies with other flows

Data on private development assistance, including philanthropic spending, is still inadequate to paint a full, disaggregated picture of where and on what this type of financing is being spent. This makes it difficult to fully understand, and subsequently exploit, its synergies with other flows.

However, there is some standardised, disaggregated data [21] and this shows that overall spending by international foundations has increased by 47% between 2013 and 2015, reaching US$9.1 billion in 2015 (of which US$5.2 billion was from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation). Data also shows that similarly to ODA, international philanthropic financing targets poor and vulnerable places more than other sources of finance (e.g. between 2013 and 2015, 42% of the share going to countries with poverty data available went to countries with a poverty headcount above 20%) and also plays an important role in human capital-related sectors, particularly health.

The role of international foundations should be considered alongside that of domestic local foundations, which is important in many countries and is also growing – between 2013 and 2015 available data (for which coverage is limited) shows a 10% increase to US$435 million. Some encouraging initiatives aim to strengthen the evidence base on this type of financing, such as Philanthropy Nigeria, which aims to reduce redundancy across Nigerian charitable organisations by making more data available on spending across the country. [22]

Public–private financing approaches, such as blending and public–private partnerships, are increasing but need substantial behavioural shifts to move investment to where they are needed most

Against the backdrop of the ambition and universality of Agenda 2030 together with concerns over stagnating aid flows, the private sector is increasingly seen as a solution for meeting the scale of investments needed to achieve the SDGs. Domestic governments and development partners alike are exploring blending and public–private partnership mechanisms to use public resources, including ODA, to leverage commercial financing toward development projects.

But while commercial actors have an important role to play in economic development and broader SDG achievement, fundamental differences in motivations and objectives prevent them from being automatic substitutes for national and international public finance. [23] While balancing commercial returns with social outcomes is a challenge, countries need both social and economic progress. There should not be a trade-off between supporting investments in social or economic goals, and the former may be a precondition for the latter, especially in the poorest countries with low levels of human capital (see Chapter 1). Efforts to mobilise additional volumes of commercial funding into development should, therefore, not be separated from considerations around the risk of diverting scarce ODA resources away from interventions with known and more direct pro-poor outcomes.

Investments in blended finance and public–private partnerships, while on an upward trend, remain short of what is needed. Private finance mobilised via blending – which is used as a proxy for blended finance investments as no data exists on how much money is invested by donors – has doubled from US$13 billion in 2012 to US$26 billion in 2015 (latest year for which country-level data is available). But volumes remain far from meeting need, such as the G20-estimated US$1.5 trillion a year for developing country infrastructure investment. Limited growth can be attributed, among other things, to low mobilisation ratios and limited supply of commercially-viable projects.

Investments are also highly concentrated in a few large emerging markets where risk is low and the business environment strong – meaning their potential to reduce the gap between the poorest and other developing countries may be limited, and unlikely in the timeframe Agenda 2030 requires. These trends have also been driven by the risk-averse mandates of many international financial institutions that need to demonstrate profitability and maintain credit ratings. Consequently, seven countries – all MICs and with poverty levels below 20% – account for over half (52%) of the country-allocable amounts mobilised in 2015. Similarly, available data on public–private partnerships shows that in 2016, almost two thirds of global investments went to five countries – Brazil, Colombia, Indonesia, Philippines and China – also all MICs and with poverty levels below 20%. [24]

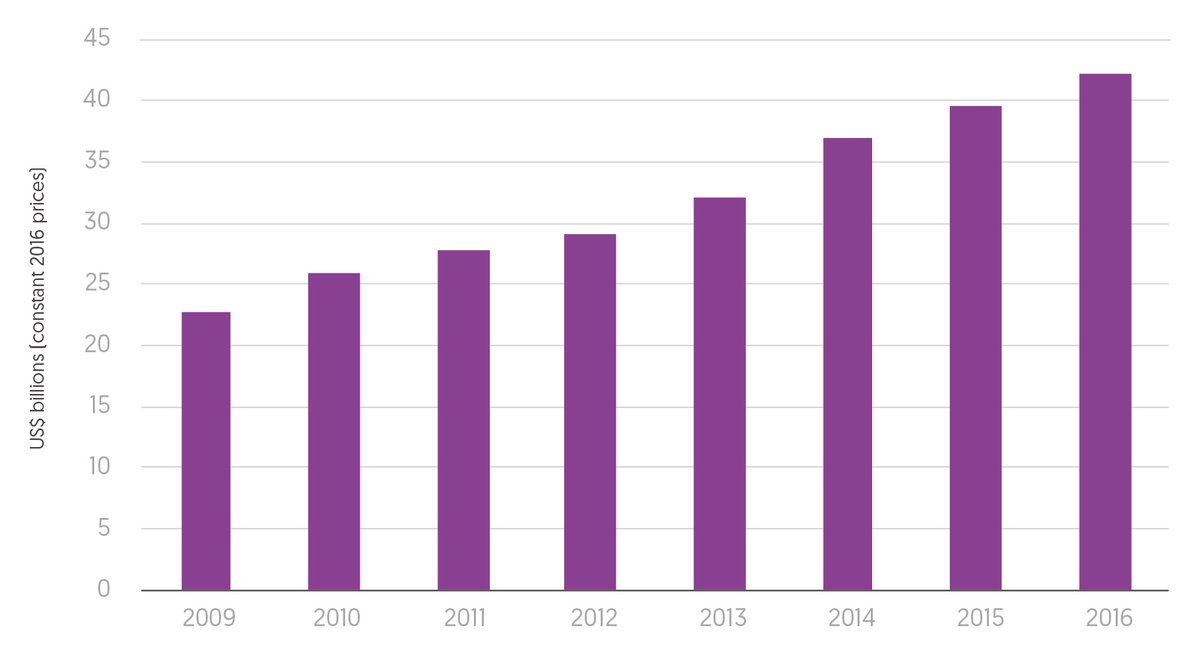

Development finance institutions (DFIs) are becoming prominent actors in the financing landscape and have an important role to play in mediating co-financing and de-risking investments, as well as making direct investments themselves. The International Finance Corporation (IFC)'s investment commitments, for example, grew from US$7.5 billion in 2011 to US$11.1 billion in 2016 (a 48% increase over five years). Between 2009 and 2016, the combined portfolios of European DFIs also grew: from US$22.6 in 2009 billion to US$42.2 billion in 2016 (equivalent to an 86% increase in real terms over seven years) (Figure 3.13). But available data again shows that the vast majority of bilateral DFIs’ investments are targeting wealthier middle-income countries. [25]

This does not mean there is no role for blended or public–private partnerships financing in the SDG agenda. Rather, their strength is in working in synergy with other concessional and commercial finance, focusing on where each is most effective in sectors and countries at different stages of development. As seen in Chapter 2, aid is spent across a broad range of countries and not always the poorest. There are opportunities, for example, to build efficiencies and release aid in places where both blended finance and ODA are significant, particularly if mobilisation ratios are improved. And by amending mandates of international financial institutions to address disincentives towards risk, they can more effectively work in the places that need it most, particularly if they incorporate a focus on building strong government partnerships and a healthy business environment.

Figure 3.13 The combined portfolios of European DFIs have grown by 86% between 2009 and 2016

The combined portfolios of European DFIs have grown by 86% between 2009 and 2016

Source: EDFI Annual Report 2011 for data for 2009–2011, and data provided by EDFI for other years.

Note: Most of the European DFIs included in this chart limit their investments to developing countries, except Finnfund, which can also invest in Russia and SIMEST, which can invest in all countries, thus their figures may include non-developing countries investments too.

Box 3.4

Better data and transparency is needed to establish who benefits from public–private investments

Investing aid through public–private partnerships should be subject to scrutiny just like all ODA. If any initiative can demonstrate who is being included and who will directly benefit, with a clear emphasis on people in extreme poverty, then it should be considered a viable option.

While volumes and the prominence of public–private arrangements increase and the total portfolios of DFIs rise, their impact on the lives of the poorest people remains unclear. Data on the volumes and distribution of blended finance, public–private partnerships and broader DFIs investments has been improving in recent years, [26] but important gaps remain that limit the ability to assess what public–private finance is being spent on and, crucially, who benefits.

Poor data and a lack of evidence has left a number of key questions unaddressed, including: which types of private actors (e.g. foreign, domestic, small- and mediumsized enterprises and multinational corporations) benefit from such arrangements? What financing instruments are being used? What are the channels through which different mechanisms can benefit the poorest people in developing countries? What are the conditions for these channels to be most effective? What are the effects on local capital markets when international commercial capital is subsidised to encourage entrance into these markets? How do public–private financing mechanisms respond to nationally identified development priorities?

To ensure that public–private financing, and ODA within it, is put to its best possible use for Agenda 2030 and the leave no one behind imperative, it is crucial that action is taken to improve the quantity and quality of data and information available.

Wider forms of international financing alone are unlikely to deliver sufficient investments in human capital investment sectors in the required timeframe

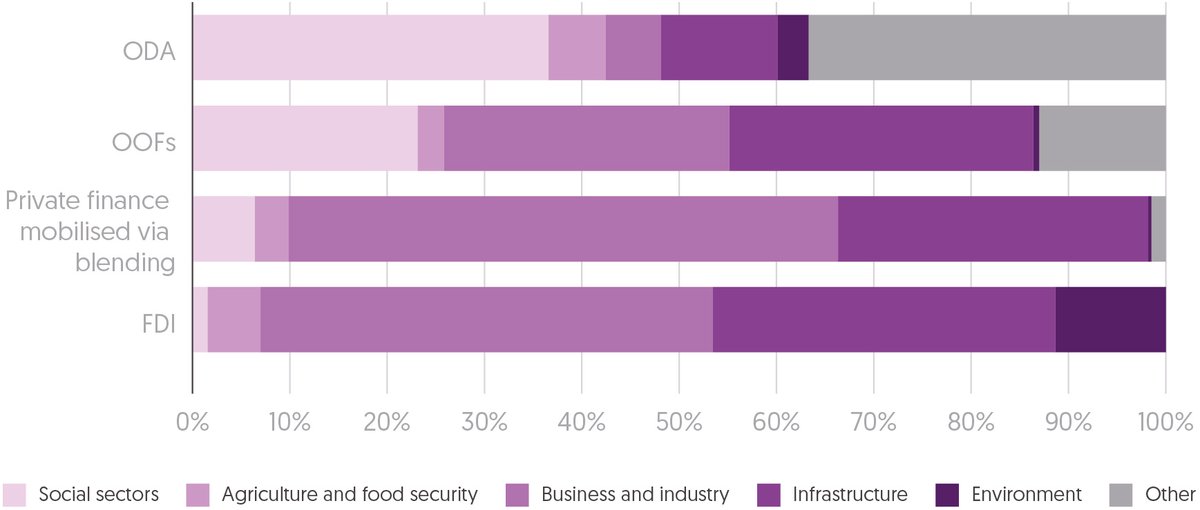

Comparable sectoral data across types of finance flows is limited but can build a picture of which sectors are being prioritised by different actors and resources. This can inform an analysis of which sectors are being ‘left behind’ by wider sources of finance and identify where investments need to be strengthened – especially sectors that are directly related to poverty reduction and human capital development such as health, education and social protection.

Non-concessional public and private flows target sectors that offer economic returns – such as productive sectors and infrastructure projects – more than social sectors such as health and education (Figure 3.14). Just under a third of OOFs spending and private finance mobilised via blending targets infrastructure projects (including energy, communications and transport). A significant proportion of private finance mobilised via blending (56% of these flows) and FDI (46%) focuses on business and industry, which includes trade-related investments, productive industries such as construction, mining and tourism, and banking and financial services.

Figure 3.14 Non-ODA financing targets infrastructure and business and industry more than social sectors

Non-ODA financing targets infrastructure and business and industry more than social sectors

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD and fDi Markets from Financial Times Ltd.

Notes: Data for ODA, other official flows (OOFs) and FDI is for 2016; data for private finance mobilised is for 2012– 2015. FDI data is based on announcements of planned investments, not actual recorded flows.

So, while substantial overall, wider sources of finance not only bypass the poorest countries and those most at risk of being left behind but also social sectors. This is not surprising. But when combined, the figures are stark: only 5.7% of FDI to developing countries for which a sectoral breakdown is available goes to countries where over 20% of people live in extreme poverty; and of that, just 1.6% goes to sectors that directly support investments that promote developing a country’s human capital. This means only 0.1% of the global total accounts for investments in human capital sectors in high poverty countries. [27]

This is not to say that wider forms of financing, including commercial resources, cannot have an important impact on poverty reduction and human capital development. For example, in 2016, FDI projects in developing countries created 1.4 million jobs across various industries, notably transport, ICT and electronics and construction. And in the same year, almost 2% of FDI projects (99 of 5,339) in developing countries – accounting for US$986 million – involved education and training activities, a percentage that, though small, has increased from 0.7% in 2003. [28]

But while this may indeed signify future potential, the extent to which wider forms of finance are likely to provide the urgent investment needed for Agenda 2030 now – particularly in areas of human capital – is limited.

Box 3.5

International businesses and industries are stepping up to the SDGs but much more is needed to meet the commitments

There are increasing examples of industries and multinational corporations embracing the SDGs in their business models and recognising their shared responsibility to leave no one behind – driven at least in part by the US$12 trillion in market opportunities that the SDGs have been estimated to provide, together with the need for big business and big finance to regain public trust. [29]

In February 2016, for example, the mobile industry was the first to commit as a whole to the SDGs and through the annual impact reports GSMA has been publishing since, has created a framework to assess its impact across them. [30] Danone, a world-leading food company, has set 2030 company goals aligned with the SDGs and selected SDGs of ‘major focus’ – such as SDG2 (no hunger) and SDG3 (health) – and others to which it is committed, which include SDG1. [31] More broadly, initiatives like the UN Global Compact – the world’s largest corporate sustainability initiative with over 12,000 signatories [32] – and, more recently, Plan B [33] reflect business leaders’ growing recognition of the need to catalyse a better way of doing business, one that goes beyond maximising profit and considers the well-being of people and the planet too. And the Business Call to Action initiative continues to challenge companies around the world to develop inclusive business models to reach the poorest communities and engage people at the base of the pyramid as consumers, producers, suppliers, distributors and employees. To date it has involved over 200 companies working in 67 countries. [34]

Despite these encouraging signs, only a small proportion of businesses understand the importance of, and opportunities to be gained from, aligning to the SDGs. [35] There is, therefore, an important role for donors, domestic governments and civil society to continue to engage the business community and support efforts, including coordinating rules and incentives, that can strengthen the enabling environment for private sector actors to increase their impact.

Bringing it back to the people: the power of subnational resource data

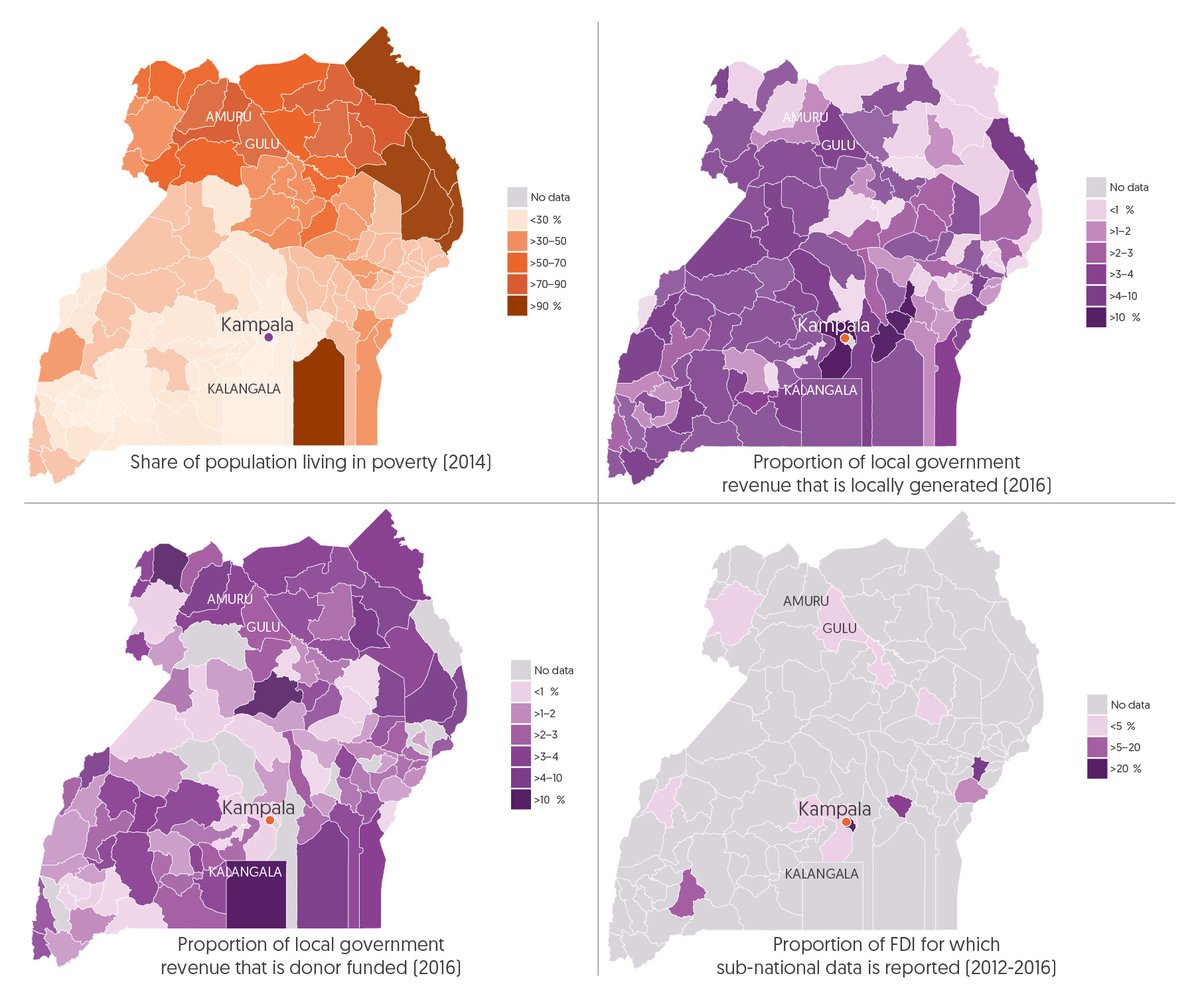

Knowing that aid goes to a particular country is a long way from understanding how it is reaching people in poverty. Mapping FDI flows to the national level tells little about who is getting jobs and benefiting from these investments. The closer resources to people and communities can be tracked, the better their impact can be truly assessed and the substantial resources available harnessed and coordinated. And given the trend of devolution of government spending in many developing countries to local level, the more this subnational information can be shared locally, the more effective all investments can be.

Data on needs and resources at subnational levels is patchy at best and rarely allows for comprehensive cross-country analysis. But data does exist, and as better data is made available and transformed into local-level information – such as Development Initiatives (DI)’s Spotlights on Kenya and Uganda [36] – the ability to map where different types of investments are and are not being made, and the ability to compare this against poverty or a plethora of other socioeconomic indicators, becomes increasingly achievable.

Data from the Spotlight on Uganda shows that the identified inverse relationship between poverty and the scale of different resources is often replicated at subnational level. For example, in the Amuru district in Uganda’s Northern Region, where 77% of the population lives below the national poverty line, only 2.5% of local government revenue is locally raised and 5.5% is donor funded. Conversely, in the Kalangala district, where the share of poor people in the local population is just 8%, locally raised revenues account for 4.2% of local government revenue and donor funds for well over a third (38%) (Figure 3.15). Higher locally raised revenues from wealthier districts may be expected; higher proportions from international aid are not.

Figure 3.15 Districts with the highest poverty tend to have proportionally less resources

Districts with the highest poverty tend to have proportionally less resources

Source: Development Initiatives’ Development Data Hub Spotlight on Uganda and fDi Markets from Financial Times Ltd.

Notes: Poverty data is for 2014 and relates to the proportion of people living under the national poverty line; data on the proportion of local government revenue that is locally raised and donor funded is for 2016.

Investments from other sources such as FDI follow a similar trend. Between 2012 and 2016 FDI in Kampala – where 4% of the population lives under the national poverty line – accounted for over a third (37%) of all FDI to Uganda. In 2016 alone, over half of all FDI flowing to Uganda (55%) and six of the eight projects for which a destination city was reported were in Kampala. This compares with areas beyond Kampala, where poverty levels are higher, which receive less (and less stable) FDI. For example, the Gulu district where poverty rates reach 69% accounted for only 1.4% of all FDI to Uganda between 2012 and 2016.

Both governments and donors can take action based on better availability and use of local data, as Chapter 4 addresses. Factors such as poor road and transport networks coupled with sparse populations, and less vibrant private sector activity can at least explain partly why locally raised revenues in poorer districts are lower and why commercial financing such as FDI does not often venture far from the capital city. But governments can provide incentives to encourage FDI to target poorer regions, bringing with it jobs and infrastructure. Myanmar, for example, explicitly links its strategy to providing such geographic incentives to SDG1. [37] Donors too, need to strengthen the support they provide to the poorest subnational areas – where poverty is high and other investments are low – cognisant that it is at that level that individual people, including those most at risk of being left behind, can be directly reached.

Downloads

Notes

-

1

A study by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network suggests that the SDGs are affordable and the challenge is mainly one of organisation and implementation: SDSN, 2015. Investment Needs to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: http://unsdsn.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/151112-SDG-Financing-Needs.pdfReturn to source text

-

2

Resources considered in this chapter include: Domestic public: non-grant government revenue. Domestic commercial: domestic credit to the private sector. Inflows: International official: ODA, development cooperation from other government providers, OOFs, export credits, official long-term debt. International commercial: FDI, commercial long-term debt, short-term debt, portfolio equity, private finance mobilised via blending. International private: remittances, private development assistance, international tourism receipts. Outflows: International official: ODA interest payments, ODA capital repayments, OOFs interest payments, OOFs capital repayments, official long-term debt interest payments, official long-term debt capital repayments, repayments on officially supported export credits. International commercial: FDI, outflows of profits on FDI, commercial long-term debt interest payments, commercial long-term debt capital repayments, short-term debt interest payments. International private: remittances, international tourism expenditures.Return to source text

-

3

IMF, 2017. IMF Fiscal Monitor: Tackling Inequality. Available at: www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2017/10/05/fiscal-monitor-october-2017Return to source text

-

4

Projections assume a constant government revenue-to-GDP ratio. Real GDP growth is available at the source until 2023; growth for 2024 to 2030 is set equal to 2023 at country level.Return to source text

-

5

Manuel M., Desai H., Samman E. and Evans, M., 2018. Financing the end of extreme poverty. Overseas Development Institute (ODI) Report, available at: www.odi.org/publications/11187-financing-end-extreme-povertyReturn to source text