Poverty in Uganda: National and regional data and trends

This factsheet explores national and regional poverty data and trends in Uganda, and compares these to socioeconomic indicators in education, health and WASH.

DownloadsKey findings

- Uganda remains among the poorest nations in the world despite reducing its poverty rate. In 1993, 56.4% of the population was below the national poverty line, this decreased to 19.7% by 2013.

- Although poverty rates overall fell between 1993 and 2016, they rose slightly between 2013 and 2016.

- While the proportion of people defined as ‘poor’ has fallen, the proportion of people who live above the poverty line but remain vulnerable to falling below it has increased. [1]

- This grouping – people who are not poor but are vulnerable to poverty [2] – are most likely to fall below the poverty line due to negative shocks, such as the effects of Covid-19.

- Falling poverty at the national level masks less positive regional trends. Recent years have seen poverty headcounts increase in eastern, western and central Uganda.

- There are also disparities between regions in non-economic proxies of poverty, such as sector performance indicators in education, health and WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene).

- There are gaps in Uganda’s poverty data, which is highly concentrated at national and regional level. There has been no official publication of district and parish-level poverty statistics since 2014.

- Uganda’s national poverty line was set in 1990 at between US$0.88 and US$1.04 per person per day (the variation depends on region). It gives a much more positive view of poverty trends than the World Bank’s US$1.90 per person per day extreme poverty line – which was updated in 2015. (Both poverty lines are covered in this factsheet.)

Introduction

What is poverty?

To live in poverty is to lack the resources needed to meet basic needs. It can be measured in economic terms (income, expenditure or wealth), or using other measures including social, nutritional and cultural (or even multidimensional measures).

Poverty can be defined by a fixed value (absolute poverty) or by a value in relation to the rest of the population (relative poverty). Absolute poverty is measured by the minimum amount of money required to meet basic needs, known as a poverty line. The international standard for measuring poverty is the extreme poverty line. This measure of absolute poverty has a threshold equivalent to US$1.90 per person per day. You can learn more about poverty in our factsheet Poverty trends: global, regional and national .

How has Uganda dealt with poverty and development?

Uganda is a low-income county and among the poorest countries in the world. In Uganda, absolute poverty is officially defined as a ‘condition of extreme deprivation of human needs, characterised by the inability of individuals or households to meet or access the minimum requirements for decent human wellbeing such as nutrition, health, literacy and shelter’. [3]

Uganda’s economy had collapsed when the National Resistance Movement (NRM) took power through a civil war in 1986. The NRM embarked on an ambitious economic plan, dubbed the Economic Recovery Programme (ERP), with the support of the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and other donors. [4]

The programme (the first of seven major poverty eradication initiatives in Uganda to date) emphasised infrastructural development, and between 1986 and 1996 the economy of Uganda achieved an average growth of 6.5%. Despite the chaotic 1970s and 1980s (when the economy was beset by a multitude of setbacks including civil wars and other social economic instabilities) [5] the NRM government showed promise and was cited by donors as a success story for other nations to learn from.

By 1995 it was evident that ten years of rapid macroeconomic growth had not resulted in the accompanying reduction in poverty anticipated by the architects of the approach, especially the ERP. [6] In 1997, therefore, the Poverty Eradication Action Plan (PEAP) was established. [7] The PEAP set out clear strategies for the prioritisation of public expenditure to key programmes geared to reducing poverty.

Despite the slow pace of the recovery, the government’s macroeconomic policies had a tremendous impact in reducing poverty levels. These decreased from over 56% of the population living below Uganda’s national poverty line in the early 1990s to just below 20% within a period of nearly 20 years.

Uganda’s National Development Plan (NDP) is part of a series of plans that aim to build on the achievements of PEAP and lift the country into middle-income status by 2030. The PEAP was replaced by the first NDP 2010/11–2014/15. [8] This five-year blueprint focused on new development priorities heavily skewed towards socioeconomic transformation (unlike the PEAP, which had emphasised poverty eradication and therefore focused on social services).

The second NDP, running from 2015/2016 to 2019/2020, aimed to strengthen Uganda’s competitiveness regionally and internationally and thus create sustainable wealth, employment and inclusive growth. It focused on agriculture, tourism, mineral extraction, oil and gas, infrastructure and human capital, with the goal of transforming Uganda into a middle-income country by 2020. [9] Unfortunately, many of these aspirations have not been realised and Uganda remains a low-income country in 2020.

Uganda’s current development focus therefore is one that emphasises wealth creation and infrastructure development. Despite these policies, Uganda’s economic growth has tapered off, averaging 3–4% from 2015 onwards. The economy remains small (GDP US$25 billion) and heavily reliant on donor funding. [10]

Uganda’s national poverty line has been fixed at US$0.88–US$1.04 since 1990. [11] This is notable because the way people live in Uganda has altered dramatically since the 1990s. For example, access to mobile phone technology and the costs of goods and services have changed.

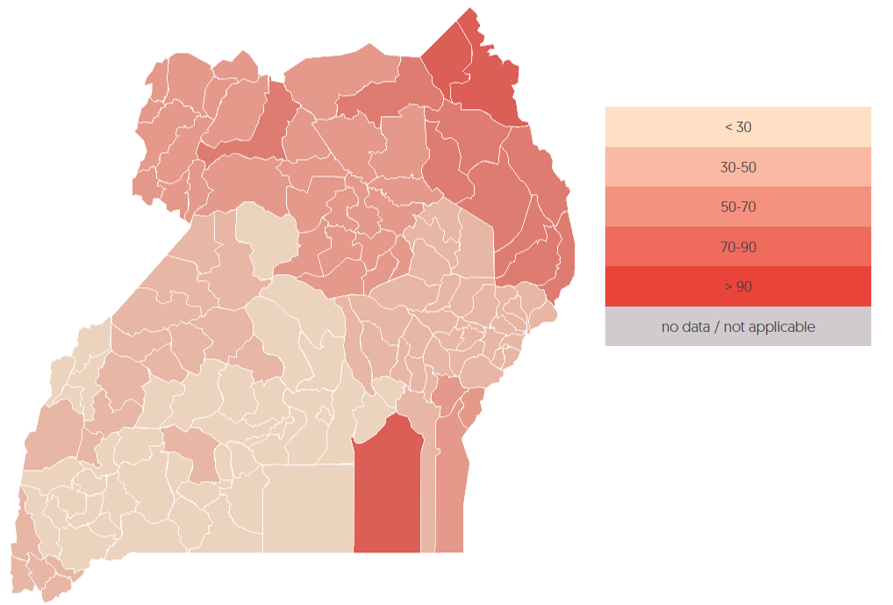

Mapping the most recent extreme poverty data reveals that northern and eastern parts of Uganda have higher poverty headcounts than the other parts of the country (Figure 1). District-level data can be used to perform comparative analysis and sub-regional analysis.

Figure 1: Northern and eastern parts of Uganda have higher poverty headcounts compared to rest of the country

A heatmap showing that the northern and eastern regions of Uganda have higher poverty headcounts compared to rest of the country

Source: Development Initiatives.

Notes: The poverty headcount on the map is based on the 2011 international poverty line (PPP$1.90 per day). It does not consider the depth of poverty. The data year is 2014 as per the source document publication date.

Covid-19’s impact on Uganda’s fight against poverty

Uganda instituted some of the harshest measures on the African continent following the outbreak of Covid-19. In March 2020, even before a single case was registered in the country, the government closed its air, land and sea borders. Movement was restricted; schools, churches and shops were shut down; and the military enforced these measures with an iron hand. This gutted the largely informal economy, and the Ministry of Finance’s growth projections for 2020 were reduced from 6% to 4%. The government of Uganda estimates that poverty numbers, according to the national poverty line, could increase by 2.6 million people. [12] Our report The socioeconomic impact of Covid-19 in Uganda provides additional details on the effects of Covid-19 on poverty.

National-level poverty trends

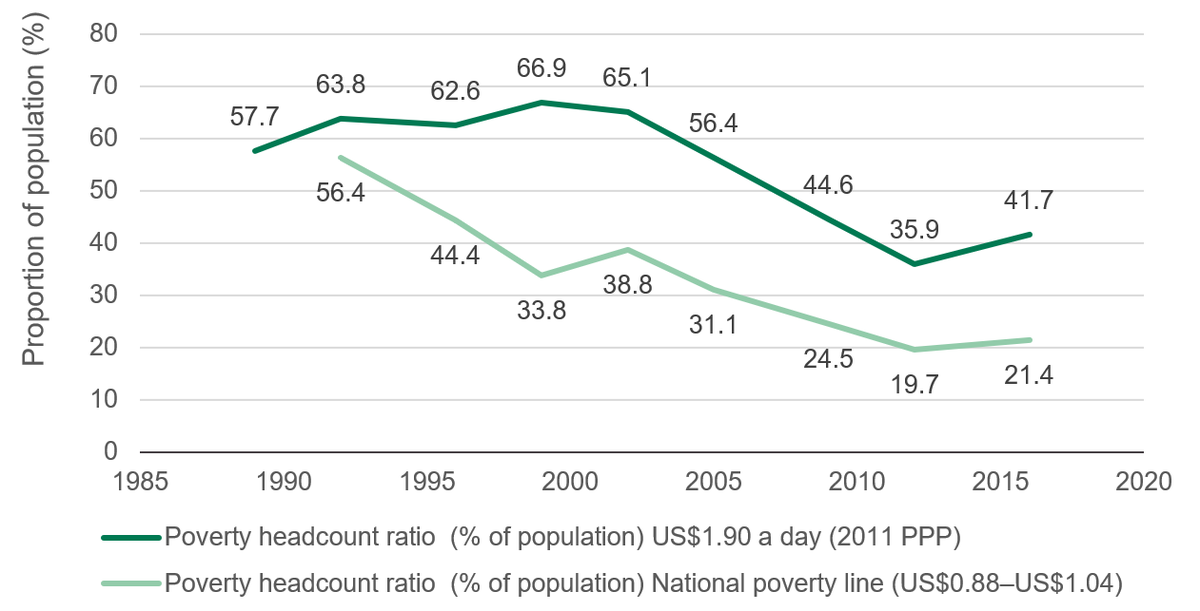

Uganda has achieved significant milestones in its fight against poverty over the past three decades, with poverty rates standing at 21.4% in 2016, down from 56.0% in 1993 (Figure 2) – according to the national poverty line. Although levels are higher according to the international poverty line, the trend is also an overall decline in this period.

However, the proportion of people living in poverty according to the national poverty line increased by 1.7% between 2012 and 2016. The international poverty line of $1.90 measure also shows an increase, and at a much higher level, with 41.7% of the population living in extreme poverty as of 2016 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: There has been an overall decline in poverty between 1993 and 2016

Line chart showing an overall decline in poverty between 1993 and 2016 in Uganda, both according to the national poverty line and the World Bank's measure

Source: Development Initiatives, based on poverty headcount data from the World Bank. [13]

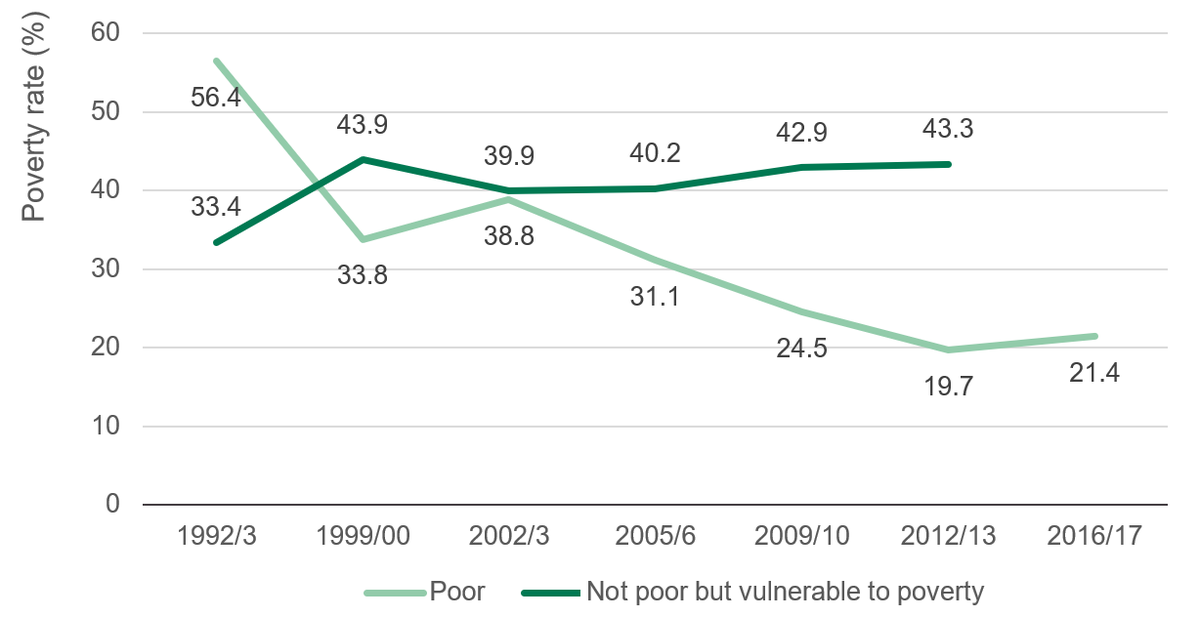

While the poverty rate has fallen over time, the proportion of Ugandans classified as not poor but vulnerable to falling below the poverty line has increased. ‘Not poor but vulnerable’ refers to those living on an income that is above the national poverty line but less than double the national poverty line. They are not living in absolute poverty but are poor relative to the middle class and are vulnerable to falling below the poverty line in the face of a negative shock.

This increase suggests that Uganda has been successful in reducing income poverty but less so in preventing it. [14] In 2013, 43% of Ugandans (14.7 million people) were vulnerable to falling below the poverty line (Figure 2). While no official total has been published since, it is highly likely that many more Ugandans have fallen below the poverty line between 2013 and 2016, during which time Uganda’s poverty rate increased by about 2%. In 2013, 63% of Uganda’s population was either living in poverty or vulnerable to poverty (Figure 3).

Figure 3: There is an increasing number of people who are not poor but vulnerable to falling below the poverty line (1992/93–2016/17)

Line chart showing an increasing number of people who are not poor but vulnerable to falling below the poverty line (1992/93–2016/17)

Source: Development Initiatives based on data from the World Bank. [15]

Note: Statistics are based on the national poverty line of US$0.88–US$1.04 per person per day.

Regional-level poverty trends

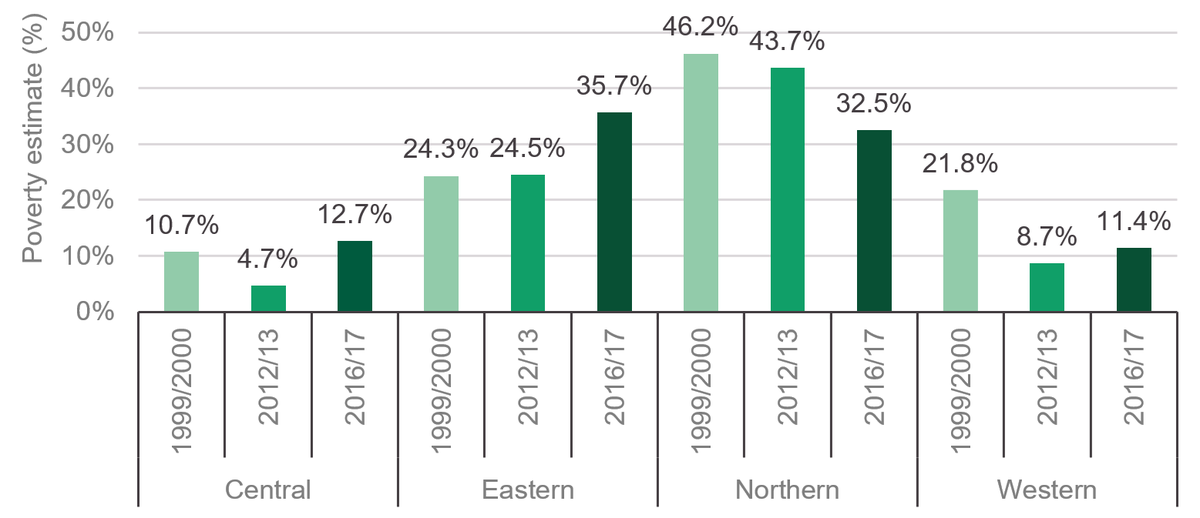

Uganda has experienced increasing regional inequalities since the 1990s. [16] While extreme poverty at a national level has generally declined since 1990s, this trend has not occurred evenly across the country. Although northern and western regions have seen a decrease in the share of population in poverty since the 1990s, the eastern region has recorded an increase in poverty (from 24.3% in 1999/2000 to 35.7% in 2016/17), overtaking the northern region as the poorest. Similarly, poverty rates in the central region increased from 10.7% in 1999/2000 to 12.7% in 2016/17. Even in the regions where both the share and number of people living below the national poverty line has generally decreased since 1990, there are stark differences between the rates of change at regional level (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Eastern region is now the poorest region, as poverty increases in all regions apart from northern Uganda (1992/93–2016/17)

Bar chart showing poverty levels for Uganda's regions. Eastern region is now the poorest region, as poverty increases in all regions apart from northern Uganda (1992/93–2016/17)

Source: Development Initiatives based on data from Uganda Bureau of Statistics. [17]

Notes: Poverty rates are based on the national poverty line.

Poverty has increased between 2012/13 and 2016/17 in all of Uganda’s regions except in northern Uganda where poverty fell from 43.7% to 32.5% (based on the national poverty line). Historically, northern Uganda’s high poverty rate is mainly attributed to over two decades of civil war between the government and the Lord’s Resistance Army rebels of Joseph Kony. [18] The more recent trend is partly due to the government poverty reduction programmes that have rejuvenated agricultural livelihoods in that region, which is now peaceful. [19]

The data shows that most of Uganda’s poverty remains concentrated in northern and eastern parts of the country. While the poverty rates in central and western regions have historically been lower than that of eastern and northern Uganda, these two regions have recently recorded increases in poverty.

The next section examines disparities between regions across a range of indicators on poverty and those relevant to poverty reduction.

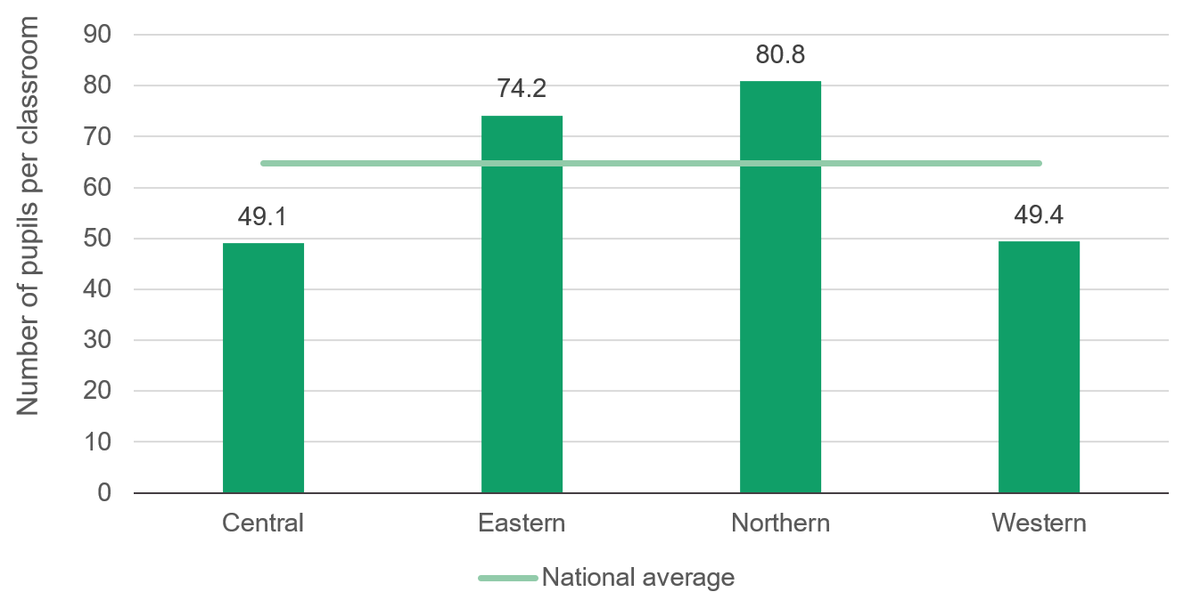

Education indicators and regional poverty

Eastern Uganda, the region with the highest poverty rate, has some of the highest pupil-to-classroom ratios – much higher than the national average of 65 pupils per classroom (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Northern and eastern Uganda have higher pupil-to-classroom ratios

Bar chart showing that Northern and eastern Uganda have higher-than-average pupil-to-classroom ratios

Source: Development Initiatives. Based on data from 2014 annual education sector statistical abstract, Ministry of Education.

Note: ‘Pupil–class ratio’ is the primary pupil-to-classroom ratio for all schools (both private and public).

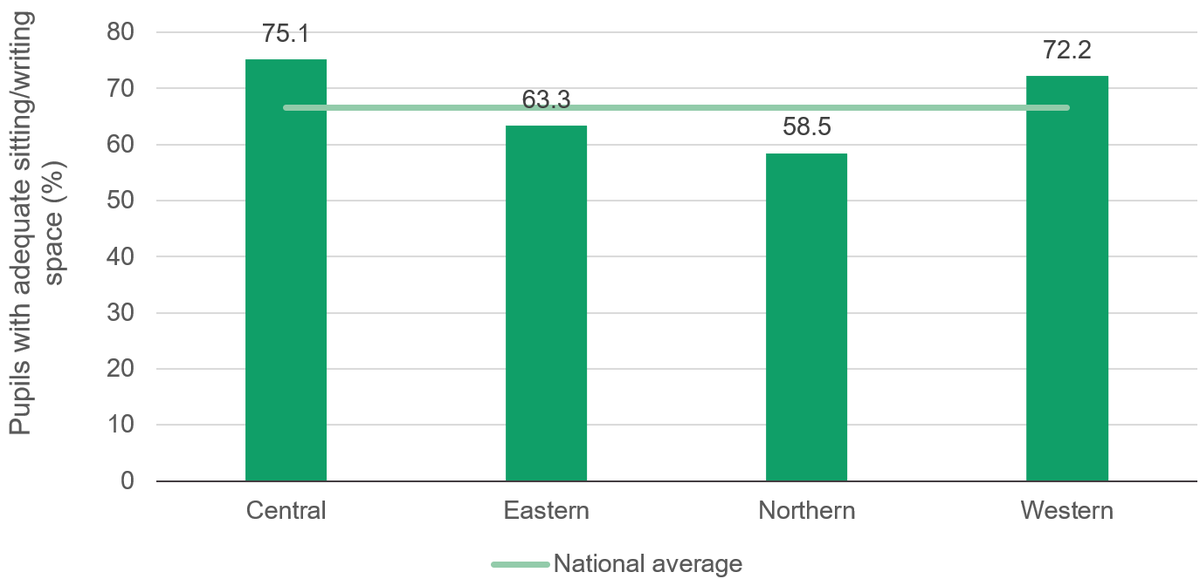

Eastern and northern Uganda, the regions with the highest average poverty rates in the country, have the lowest proportions of pupils with adequate space for sitting and writing (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Northern and eastern Uganda have lower proportions of pupils with adequate sitting and writing space

Bar chart showing that northern and eastern Uganda have lower proportions of pupils with adequate sitting and writing space

Source: Development Initiatives. Based on data from 2014 annual education sector statistical abstract, Ministry of Education.

Note: This indicator refers to the percentage of primary school pupils in government- and private-run educational facilities who have adequate reading and writing space in their classrooms.

Health indicators and regional poverty

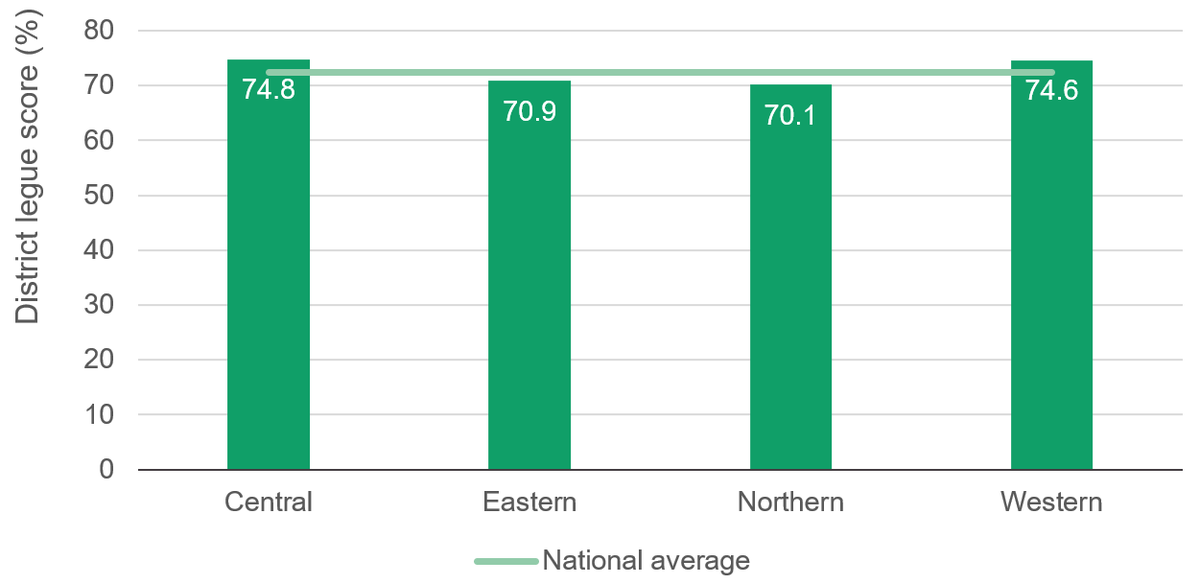

The performance of districts against health indicators is measured by a score referred to as ‘district league score’. This is a composite index based on performance against all district health indicators. The higher the score, the better the rated performance (with 0 the lowest score possible and 100 the highest). On average, districts in northern and eastern regions scored lower than those in central and western regions (Figure 7). This implies that the populations in regions with lower health scores experienced poorer quality of health services than those in regions with better scores. [20]

Figure 7: On average, districts in eastern and northern Uganda score lower against health indicators than the national average, and lower than western and central regions

Bar chart showing that on average, districts in eastern and northern Uganda score lower against health indicators than the national average, and lower than western and central regions

Source: Development Initiatives. Based on data from Uganda Bureau of Statistics.

Note: Health score is a composite index based on performance of all district health indicators. The higher the score the better the rated performance, with 0 the lowest score possible and 100 the highest.

WASH indicators and regional poverty

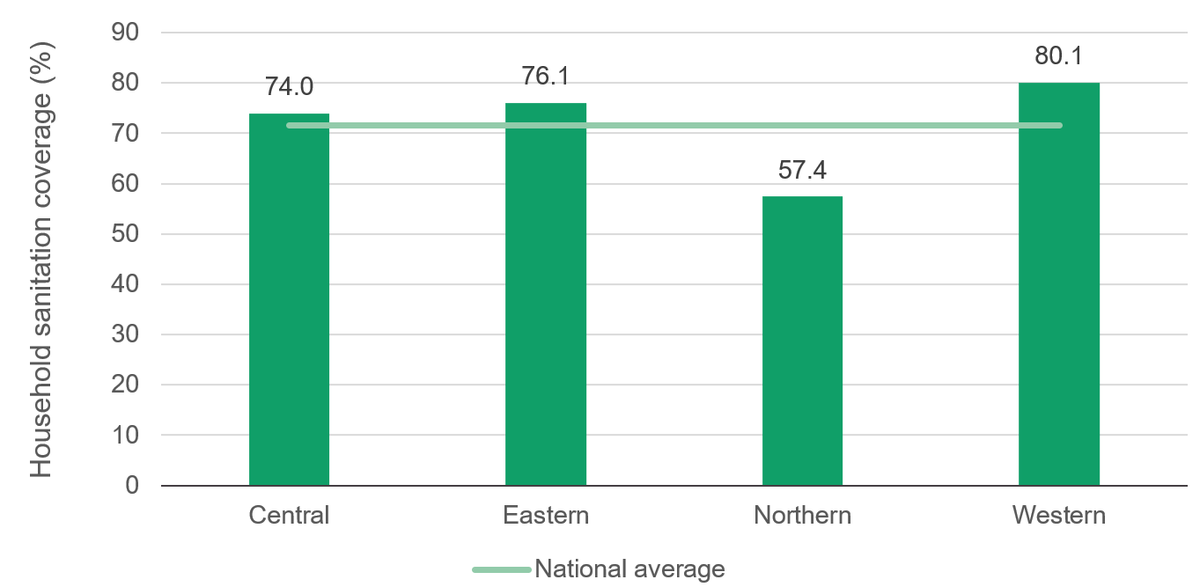

The eastern region performed second best, and above the national average, on household sanitation coverage. Northern Uganda with the second highest poverty rates in 2016/17, performed lowest in household sanitation coverage compared to other regions (Figure 8).

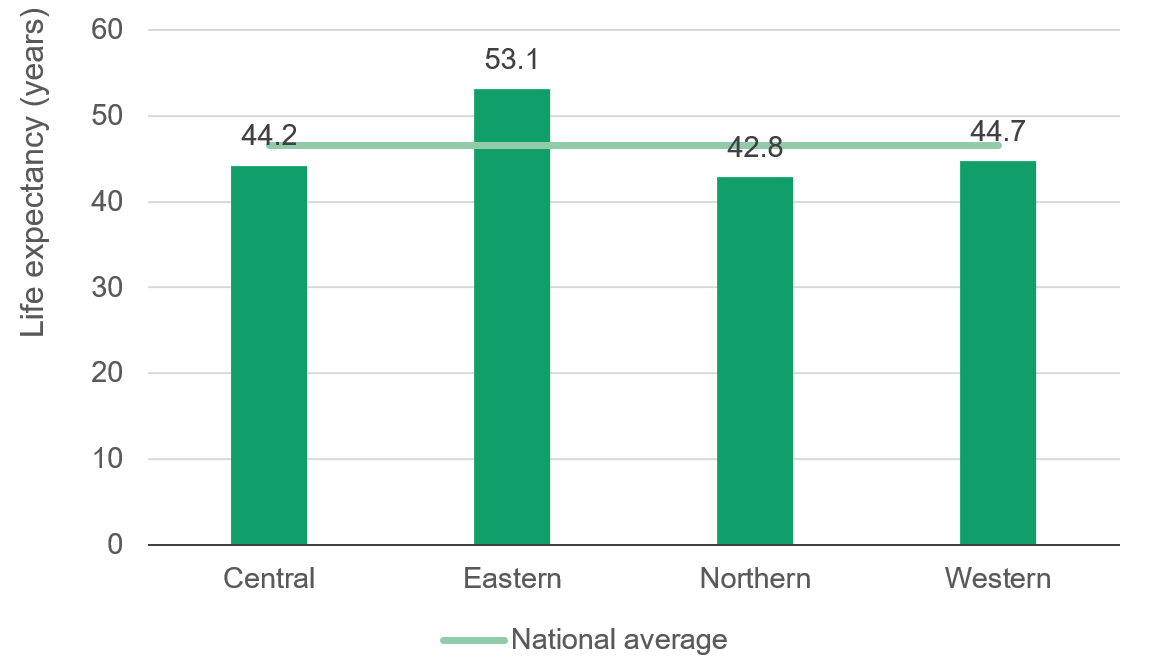

Life expectancy and regional poverty

While in some cases, poor performance against development indicators has a correlation with higher poverty headcount, this is not true for life expectancy (Figure 9). It is also true for some other indicators, such as proportion of households receiving remittances: eastern Uganda, which with the highest poverty rate in 2016, performed better than other regions.

Figure 9: Eastern Uganda has higher average life expectancy (years) than the better-off western and central regions

Bar chart showing that eastern Uganda has higher average life expectancy (years) than the better-off western and central regions

Source: Development Initiatives

Notes: Life expectancy here is the average number of years that a person can expect to live in 'full health'. It considers years lived in less than full health due to disease and/or injury. Life expectancy is normally determined at birth but can be derived at any other age based on the current death rates.

How good is Uganda’s poverty data?

Uganda’s poverty estimate data is based on US$0.88–US$1.04 per person per day as the national poverty line. This measure is much lower than the World Bank’s international figure of US$1.90. Therefore, Uganda’s poverty estimate of 21.7% in 2016 is much lower than the 41.7% in 2016 calculated using the international measure of extreme poverty.

The household surveys conducted by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) are the key source of Uganda’s poverty data. While UBOS has made efforts to survey at regular intervals, most of these surveys are based on narrow samples that have not produced representative and accurate estimates of poverty at subnational levels (across districts and parishes).

In terms of frequency, Uganda has produced three key sources of poverty data that include household income and expenditure in the period from 2000 to 2020: the 2005/6, 1999/2000, 2012/13 and 2016/17 national household surveys. There is also data from the demographic and health surveys (DHS) for 2000/01, 2005/06, 2010/11 and 2016/17 carried out after every five years. These surveys do not collect data on household income or expenditure; however, they do record several household characteristics that are likely to be related to standard of living. [21]

Uganda also produced the 2014 national population and housing census (which also did not include household consumption or income data) but its wide coverage of household characteristics is assumed to increase the precision of imputed household consumption. [22]

Of all the above sources, only the poverty estimates data from the 2014 census has been officially published at district, regional and national level. The other sources provide poverty estimate data at regional and national levels only. The lack of regular and consistent subnational disaggregated data is a gap in Uganda’s poverty data.

A key challenge with Uganda’s district and sub-district poverty data is the frequent creation of new districts and other administrative units. This makes it difficult to track and map progress as it would necessitate regular revision of geography files each time a new district is created. [23] This has also made it hard to accurately track poverty statistics over time for districts whose boundaries have changed after publication of the most recently available poverty data.

Downloads

Notes

-

1

The World Bank, 2016. The Uganda poverty assessment report 2016. Available at: http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/381951474255092375/pdf/Uganda-Poverty-Assessment-Report-2016.pdfReturn to source text

-

2

‘Not poor but vulnerable’ refers to those living on an income that is above the national poverty line but less than double the national poverty line. They are not living in absolute poverty but are poor relative to the middle class and are vulnerable to falling below the poverty line in the face of a negative shock.Return to source text

-

3

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), 2012. Compendium of Statistical Concepts and Definitions [Edition IV]. Kampala: Uganda Bureau of Statistics. Available at: https://www.ubos.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/03_2018Compendium_Vol4.pdfReturn to source text

-

4

The World Bank, 1987. Uganda - Economic Recovery Programme. Available at: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/169341468110057350/uganda-economic-recovery-program (accessed 17 September 2020)Return to source text

-

5

OECD, 1999. Is Uganda an emerging economy? A report for the OECD project “Emerging Africa”. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/countries/uganda/2674943.pdfReturn to source text

Related content

National factors helping aid-funded programmes deliver: Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia

Results from case studies on social protection, agriculture and health, programmes receiving ODA in Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia

ODA financing the climate–gender–disability interface: Key facts

Donors and African domestic budget allocators must consider the impact of climate change on women and girls with disabilities when making financing decisions

Vulnerability and resilience: How does Uganda’s data ecosystem inform social protection systems?

This report assesses Uganda's vulnerability and resilience data landscape. It evaluates the data ecosystem that informs social protection systems and makes recommendations to leave no one behind.