Private funding for international humanitarian assistance

Who provides private funding for humanitarian assistance, what are the key trends in type and volume and how could greater transparency support crisis response?

DownloadsIntroduction

The impact of Covid-19 means humanitarian funding is being spread more thinly than ever. With the gap between needs and finance continuing to grow, funding from public donors (referring to funding from governments and EU institutions) is not keeping up with requirements. [1] In 2020, total international humanitarian assistance failed to grow for the second year running and in light of the ongoing impacts of the pandemic, calls to diversify and widen the resource base of the humanitarian system, including increasing private donor funding, are more relevant than ever. [2]

Private actors play many different roles in humanitarian response, including as service providers, investors and funders. This briefing focuses on the role of private actors as donors of international humanitarian assistance (rather than of domestic assistance). Private individuals, trusts, foundations, companies and corporations have long been important contributors of international humanitarian financing and have consistently provided more than a fifth of total humanitarian funding every year – more than the humanitarian budgets of the second- and third-largest public donors (Germany and the UK) combined.

Despite the large contributions from private donors, there is a stark lack of data available on who provides it and where it goes, with no systematic reporting of private contributions from either donors or recipients. In an effort to fill this data gap, DI compiles an annual dataset through a survey to recipient organisations to calculate the annual volume of private humanitarian funding, broken down by donor type. We publish this data each year as part of the Global Humanitarian Assistance (GHA) report . While this provides a top-line estimate of the quantity of humanitarian assistance from private donors, it does not provide information on the characteristics of that funding.

Box 1

Where is the private funding data in this briefing from?

Every year, DI directly request financial information from humanitarian delivery agencies (including NGOs, multilateral agencies and the Red Cross Red Crescent (RCRC)) on their income and expenditure to create a standardised dataset. Where direct data collection is not possible, we use publicly available annual reports and audited accounts. For the most recent year, our dataset includes:

- A large sample of NGOs that form part of representative NGO alliances and umbrella organisations such as Oxfam International, and several large international NGOs operating independently.

- Private contributions to International Organization for Migration (IOM), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), World Food Programme (WFP) and World Health Organization (WHO).

- The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

Our private funding calculation comprises an estimate of total private humanitarian income for all organisations in this dataset. To estimate the total private humanitarian income of NGOs globally, we calculate the annual proportion that the NGOs in our dataset represent of NGOs reporting to UN OCHA Financial Tracking Service (FTS). The total private humanitarian income reported to us by the NGOs in our dataset is then scaled up accordingly. Due to limited data availability, detailed analysis covers the period 2015 to 2019.

Our 2020 private funding calculation is an estimate based on data provided by four organisations that receive large volumes of private humanitarian funding year on year, pending data from our full dataset. These are: Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), Plan International, Catholic Relief Services and Save the Children International. We calculate the average share that these four organisations’ contributions represent in our private funding figure for the five previous years (2015–2019) and use this to scale up the private funding figure gathered from these four organisations to arrive at an estimated total for 2020.

Feedback from humanitarian organisations suggests there is an interest in more granular data around private funding. This briefing note therefore develops further our existing analysis in the GHA report , exploring the current trends in private funding and identifying key gaps in knowledge. It draws on DI’s unique private funding dataset (see Where is the private funding data in this briefing from? ) and on additional data on funding characteristics collected from recipients of private funding including NGOs, UN agencies and Red Cross organisations. In addition, key informant interviews (KIIs) were conducted with eight representatives from recipient organisations including one private philanthropic organisation.

Box 2

Who are private donors?

‘Private donors’ are not a homogenous group and encompass a wide range of actors and funding types. Throughout our analysis, we disaggregate them into the following categories:

Individuals: The general public, including major individual donors.

Trusts and foundations: Private philanthropic grant-making organisations that are financed privately, through an individual, family or company (foundation), or through public fundraising that is privately administered (trust).

Companies and corporations: The private sector.

National societies: National affiliates of international organisations, mainly referring to the 192 Red Cross and Red Crescent national societies that act as independent auxiliaries to the government in the humanitarian field.

Key findings

Below we set out the questions this briefing seeks to answer, and a summary of key findings.

Who is giving and receiving private humanitarian assistance?

- Private donors contributed US$6.7 billion of international humanitarian assistance in 2019 (the most recent year for which a full dataset is available), [3] which accounted for over a fifth of total assistance. Early estimates suggest that this level of funding was maintained in 2020 (US$6.7 billion).

- Most of this is fundraised from individuals (77%) followed by trusts and foundations, companies and corporations and national societies.

- Generally, private donors fund NGOs rather than multilateral organisations, with 90% of individual giving provided to NGOs in 2019.

How flexible is humanitarian funding from private donors?

- Private funding is a critical source of flexible funding for humanitarian organisations in comparison with public funding. Our research suggests that the vast majority of funding raised from individuals is unearmarked (95%) and not time-bound.

- Philanthropic trusts and foundations, and private sector donors also provide funding with less earmarking and generally more flexibility than public donors, though there is variation. Our research found that in 2019, 40% of humanitarian funding from trusts and foundations and 57% of funding from companies and corporations was unearmarked or softly earmarked.

- Generally, trust and foundations and the private sector have different risk appetites, motivations and expertise to public donors and can be willing to fund different types of projects than those supported by public donors.

Where are the key data gaps and how can these be filled?

- Unlike public humanitarian assistance, there is currently no global mechanism for tracking private international humanitarian funding flows.

- This lack of timely, accurate data means that the true value of private humanitarian assistance is underestimated.

- A greater understanding of the existing barriers and incentives to reporting is needed to encourage more consistent tracking and improve transparency around where assistance is channelled.

How is private funding evolving, particularly where this assistance is non-financial?

- Private donors, such as corporations, also provide non-financial assistance to support humanitarian organisations and emergency response. This includes pro bono services and in-kind donations, as well as providing core business services in direct support of emergency response.

- Increasingly corporate partnerships are being used to provide the specialist skills required in crisis response, beyond the capacities of traditional humanitarian organisations.

Trends in private humanitarian assistance

How much is private international humanitarian assistance worth?

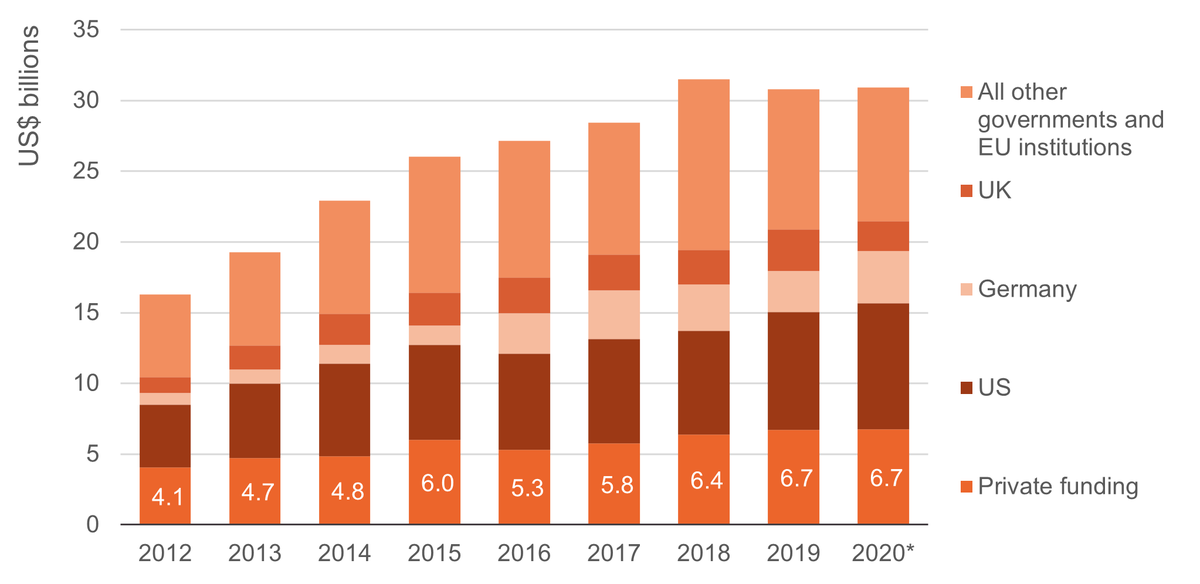

Private donors contributed an estimated combined total of US$6.7 billion of international humanitarian assistance in 2019. This represents 22% of total international humanitarian assistance that year and current estimates indicate that overall this level was maintained in 2020 (see Figure 1). [4]

Private donors have been a steady source of international humanitarian assistance throughout the last decade. On average, private contributions represented just over a fifth of all humanitarian assistance each year between 2015 and 2020. For comparison, Figure 1 also shows contributions from the three largest DAC government donors in 2020, with private donor funding regularly exceeding the combined assistance provided by Germany and the UK.

Figure 1: Private donors are significant contributors to humanitarian financing

Private and public humanitarian assistance, 2012–2020

A stacked column chart showing the breakdown of private and public humanitarian assistance from 2012 to 2020 in US$ billion. This breakdown includes the proportions of private funding, US, Germany, UK, and all other government and EU institution funding.

|

US$

millions |

2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | 4.5 | 5.3 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 6.8 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 8.3 | 8.9 |

| Germany | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 3.7 |

| UK | 1.1 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 2.1 |

|

All other governments and EU

institutions |

5.8 | 6.6 | 8.0 | 9.6 | 9.7 | 9.3 | 12.1 | 9.9 | 9.4 |

| Private funding | 4.1 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 5.8 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 6.7 |

| Total | 16.3 | 19.3 | 22.9 | 26.0 | 27.2 | 28.4 | 31.5 | 30.8 | 30.9 |

Source: Development Initiatives based on Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC), UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Financial Tracking Service, UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) and our unique dataset for private contributions.

Notes: *Figures for 2020 are preliminary estimates. Totals for previous years differ from those reported in previous Global Humanitarian Assistance reports due to deflation and updated data and methodology (see our online Methodology and definitions for more details). The US, Germany and the UK are listed as the largest DAC government donors in 2020. Data is in constant 2019 prices.

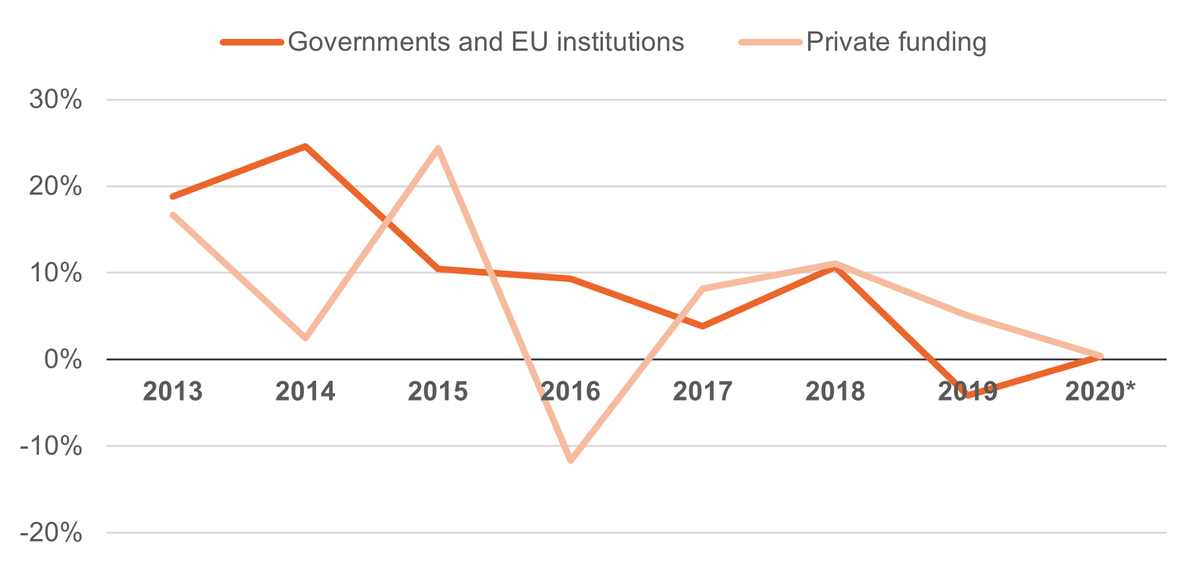

As humanitarian needs have risen, volumes of international humanitarian funding from private donors have increased though the pace of growth has slowed over time. Between 2012 and 2019, funding from private donors combined increased by 66%, from US$4.1 billion to US$6.7 billion. However, Figure 2 shows that funding growth from both public and private donors has slowed over time, with the pace of growth in private funding fluctuating slightly more, year on year, than funding from public donors. Interviews with recipient organisations found that private donors are more reactive to external events than public donors. DI analysis of private funding reported to FTS and to the Disasters Emergency Committee suggests that the spike in funding in 2015 was partly driven by support for the Syrian crisis as well as the response to the Nepal earthquake.

Figure 2: Growth in private humanitarian assistance has slowed over time

Annual percentage change in humanitarian assistance, 2013–2020

A line chart showing the annual percentage change in humanitarian assistance for government and EU institutions as well as private funding from 2013 to 2020.

| % change | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Governments and EU

institutions |

19% | 25% | 10% | 9% | 4% | 11% | -4% | 0% |

| Private funding | 17% | 2% | 24% | -12% | 8% | 11% | 5% | 0% |

| Total | 18% | 19% | 13% | 4% | 5% | 11% | -1% | 0% |

Source: Development Initiatives based on OECD DAC, OCHA Financial Tracking Service, CERF and our unique dataset for private contributions.

Notes: *Figures for 2020 are preliminary estimates. Complete data on international humanitarian assistance from private donors in 2020 will not be available until June 2022. Totals for previous years differ from those reported in previous Global Humanitarian Assistance reports due to deflation and updated data and methodology (see our online Methodology and definitions for more details). Data is in constant 2019 prices.

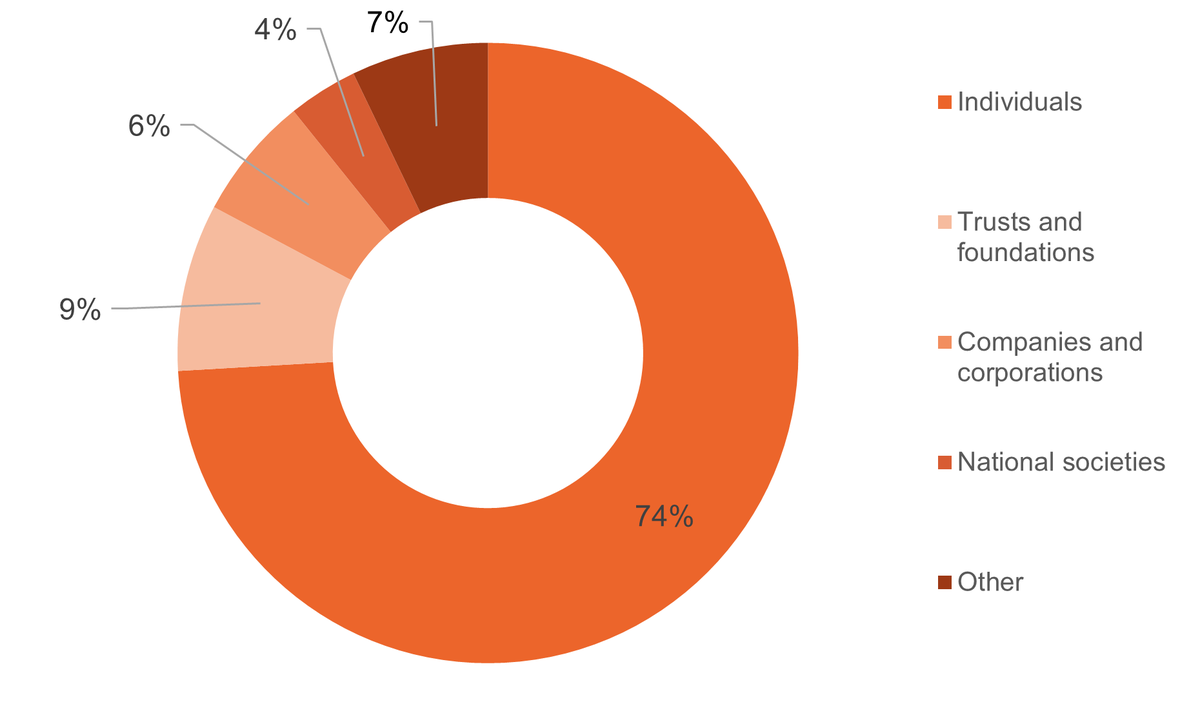

Who gives private humanitarian assistance?

By far the largest contribution of private humanitarian assistance comes from individuals. In 2019, the most recent year for which a detailed breakdown is available, individuals contributed 77% (US$4.7 billion) of all private funding, the highest proportion in the past five years. Funding from the general public encompasses a wide range of types and sizes, from one-off gifting, regular pledges and legacies to faith-based giving.

Philanthropic foundations and trusts, and the private sector, represent a smaller but consistent source of humanitarian funding. Foundations and trusts contributed 8% (US$483 million) of total private funding in 2019. These donors provide most funding as charitable grants and vary significantly in size and scope. The private sector contributed a further 7% (US$406 million) of total private funding in 2019. Companies and corporations provide funding in a range of ways, from one-off donations and grants to in-kind assistance. The proportion of private funding that these two groups contribute remained largely static in the period 2015 to 2019.

Private funding for humanitarian action is also fundraised by organisations at country-level, mainly by the Red Cross National Societies. This type of fundraising accounted for 3% (US$172 million) of total private funding in 2019. In 2019, funding from Red Cross National Societies represented 72% of the movement’s total private income. While the donors to these national affiliates differ between countries depending on fundraising strategies and country context, they can include individuals, the national private sector, foundations and governments.

Figure 3: Individuals contribute the most private humanitarian funding

Sources of private humanitarian assistance, 2015–2019

A doughnut (circular) chart showing the percentage breakdown of private humanitarian funding by individuals, trusts and foundations, companies and corporations, national societies and others. It displaces the average of 2015-2019 for each category.

| Individuals | Trusts and foundations | Companies and corporations | National societies | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 72% | 7% | 7% | 6% | 7% |

| 2016 | 72% | 10% | 7% | 2% | 9% |

| 2017 | 75% | 8% | 5% | 3% | 9% |

| 2018 | 73% | 11% | 7% | 4% | 5% |

| 2019 | 77% | 8% | 7% | 3% | 6% |

| 2015-2019 | 74% | 9% | 6% | 4% | 7% |

Source: Development Initiatives based on GHA's unique dataset of private contributions.

Notes: Data is in constant 2019 prices. Totals for previous years differ from those reported in previous Global Humanitarian Assistance reports due to deflation and updated data and methodology (see our online Methodology and definitions for more details).

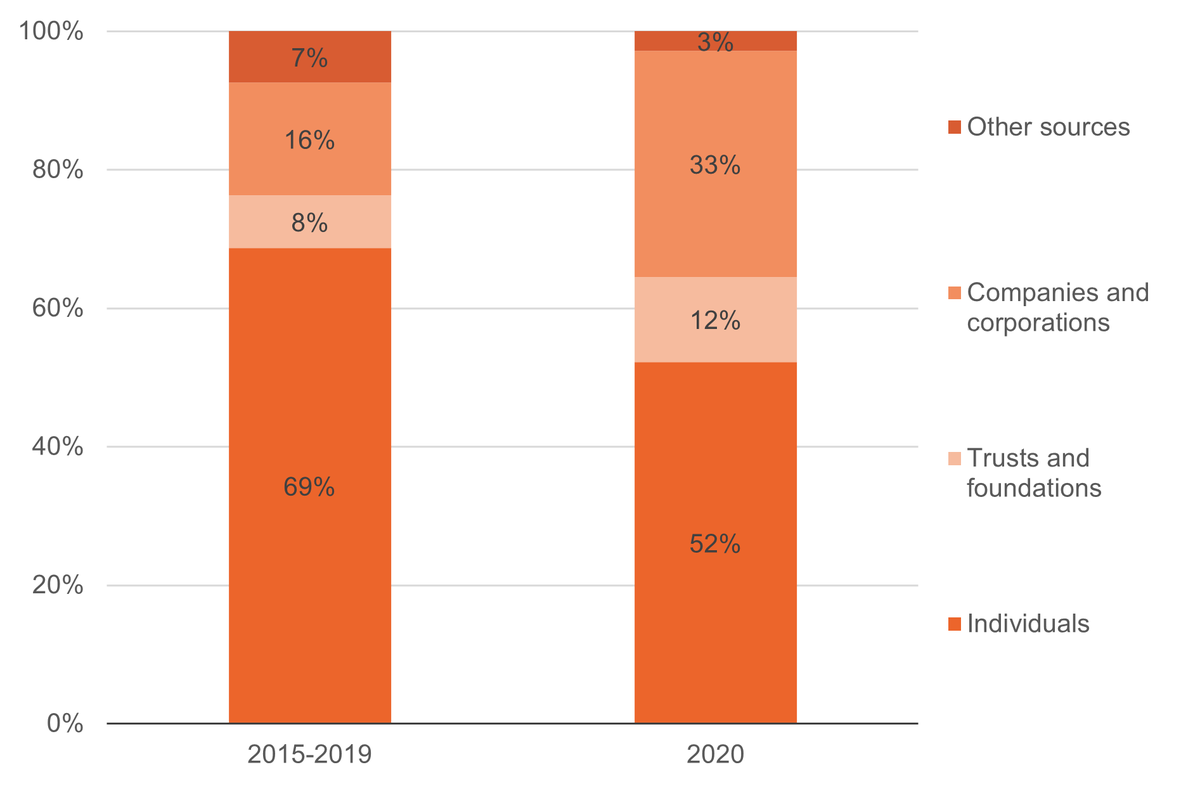

While volumes of private funding in 2020 are currently estimates (see Figure 1), 2020 funding data received directly from UNICEF suggests that some organisations saw significant increases in funding from private donors in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2020, private funding to UNICEF doubled from US$138.8 million in 2019 to US$277.8 million. Figure 4 shows that this significant growth in funding also saw the patterns of funding alter, with the private sector, and trusts and foundations, both accounting for a greater proportion of total private contributions in 2020. Assistance provided by companies and corporations grew from 16% of private funding in 2019 to 33% in 2020, a fourfold increase in volume, from US$22.2 million to US$90.6 million. Trusts and foundations also accounted for a larger share of total private assistance, growing from 7% in 2019 to 12% in 2020, an increase in volume from US$8.7 million to US$34.1 million.

Figure 4: Data from UNICEF suggests the private sector responded especially strongly to Covid-19

Private funding to UNICEF, 2015–2020

A stacked column chart showing private funding to UNICEF broken down by individuals, trusts and foundations, companies and corporations and other sources. It contrasts the average of 2015 to 2019 to 2020 in order to show changes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Year | Individuals | Trusts and foundations | Companies and corporations | Other sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015-2019 | 69% | 8% | 16% | 7% |

| 2020 | 52% | 12% | 33% | 3% |

Source: Development Initiatives based on UNICEF data.

Notes: Data is in constant 2019 prices. The majority of UNICEF’s private income is fundraised through UNICEF National Committees. Data in this chart shows the private donor source to National Committees, hence national societies have been removed as a donor category.

Who do private donors provide funding to?

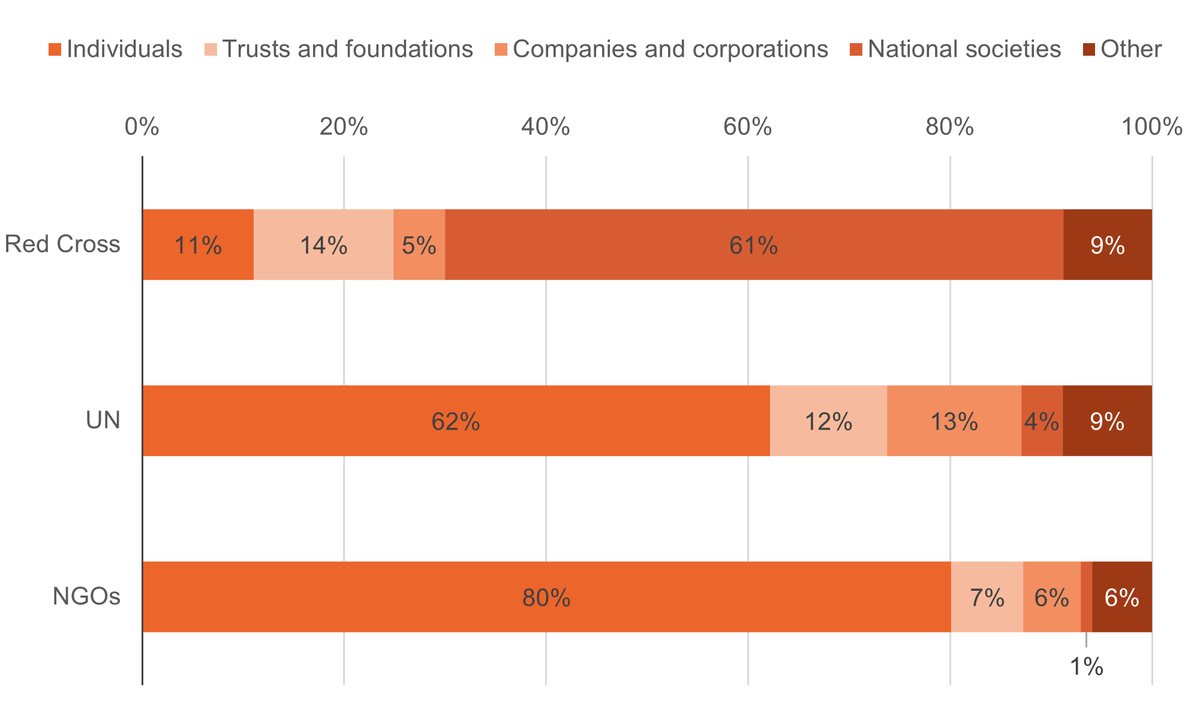

Unlike public donors which channel the majority of assistance through multilateral organisations, private donors mainly provide funding to NGOs . In 2019, an estimated 86% of total private funding was channelled to NGOs, and 12% to UN agencies.

Of this private funding, the vast majority of individual giving was to NGOs (90%). NGOs are especially reliant on funding from individuals, accounting for the bulk of their private income in 2019 (80%) (see Figure 5). Of the total humanitarian (public and private) income provided to NGOs in 2019, funding from individuals accounted for 31% on average. However this ranged between 1% and 95% for the 42 NGOs providing data, reflecting the different funding models of organisations, with some NGOs more reliant on individual fundraising than others. A slightly smaller proportion of funding provided by trusts and foundations (79%) and companies and corporations (74%) was channelled to NGOs.

Figure 5: NGOs rely on individuals for most of their private humanitarian income

Sources of private humanitarian assistance for NGOs, Red Cross, and UN agencies, 2019

A stacked percentage bar chart showing the three (Red Cross, UN, NGOs) breakdowns of private humanitarian funding by individuals, trusts and foundations, companies and corporations, national societies and others in 2019.

| Individuals | Trusts and foundations | Companies and corporations | National societies | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NGOs | 80% | 7% | 6% | 1% | 6% |

| UN | 62% | 12% | 13% | 4% | 9% |

| Red Cross | 11% | 14% | 5% | 61% | 9% |

Source: Development Initiatives based on GHA's unique dataset of private contributions.

Notes: Data is in constant 2019 prices.

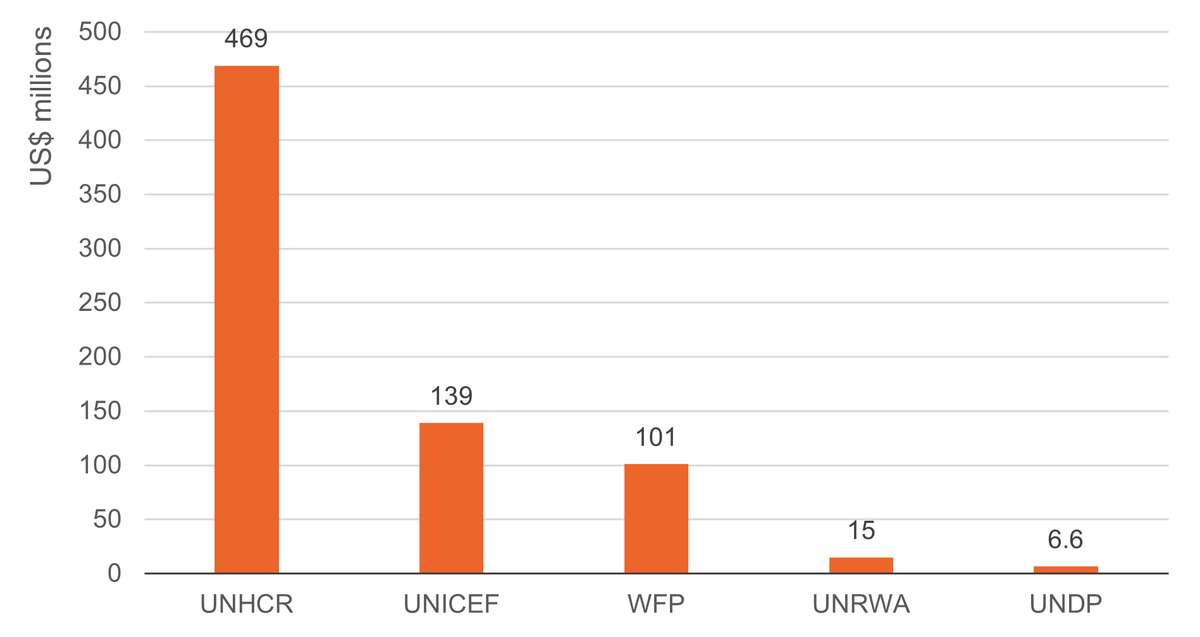

Some UN agencies rely more on private income than others (see Figure 6). UNHCR received the highest volume of funding from private donors in 2019 (US$469.1 million), which accounted for 11% of their total income that year. By contrast, just 1% (US$6.6 million) of UNDP’s total funding and 1% (US$101.0 million) of WFP’s total funding was from private donors.

Figure 6: UNHCR receives the highest volume of private humanitarian funding

UN agency private humanitarian funding, 2019

A column chart showing the private humanitarian funding received by five UN agencies including UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNRWA and UNDP in 2019 in US$ millions.

| Organisation | Total income from private sources | |

|---|---|---|

| UNHCR | 469,147,650 | |

| UNICEF | 138,832,563 | |

| WFP | 100,949,618 | |

| UNRWA | 15,182,383 | |

| UNDP | 6,642,099 |

Source: Development Initiatives based on GHA's unique dataset of private contributions.

Notes: Data is in constant 2019 prices.

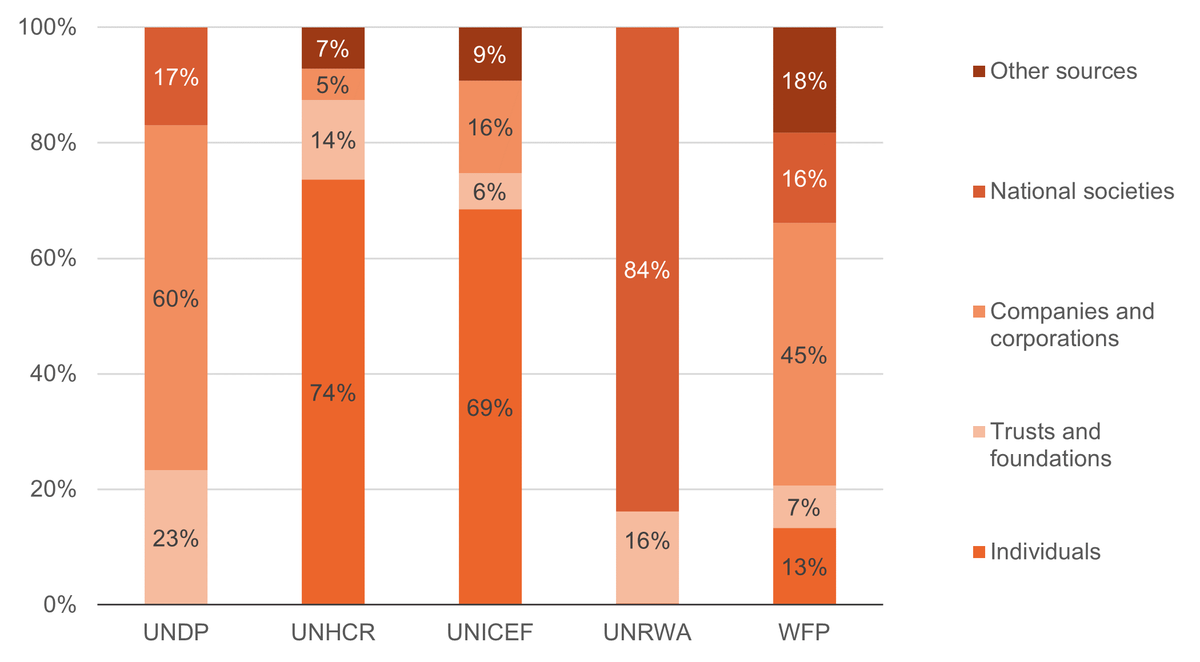

While in total, UN agencies received the majority (62%) of their private income from individuals in 2019, this also varies between agencies (see Figure 7). UNHCR (74%) and UNICEF (69%) received the highest proportion of their private income from individual fundraising while other agencies such as UNDP and UNWRA, received no income at all from individuals in 2019. UNDP and WFP relied more heavily on contributions from the private sector, accounting for 60% (US$4.0 million) of UNDP’s and 45% of WFP’s (US$46.0 million) private funding in 2019.

Figure 7: Private donors support individual UN agencies differently

Sources of private humanitarian assistance for UN agencies, 2019

A stacked percentage column chart showing the sources (individuals, trusts and foundations, companies and corporations, national societies and other sources) of private funding for five UN agencies (UNDP, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNRWA and WFP) in 2019.

| Organisation | Individuals | Trusts and foundations | Companies and corporations | National societies | Other sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNDP | 0% | 23% | 60% | 17% | 0% |

| UNHCR | 74% | 14% | 5% | 0% | 7% |

| UNICEF | 69% | 6% | 16% | 0% | 9% |

| UNRWA | 0% | 16% | 0% | 84% | 0% |

| WFP | 13% | 7% | 45% | 16% | 18% |

Source: Development Initiatives based on GHA's unique dataset of private contributions.

Notes: Data is in constant 2019 prices. Chart and analysis include data from five UN agencies that responded to our survey.

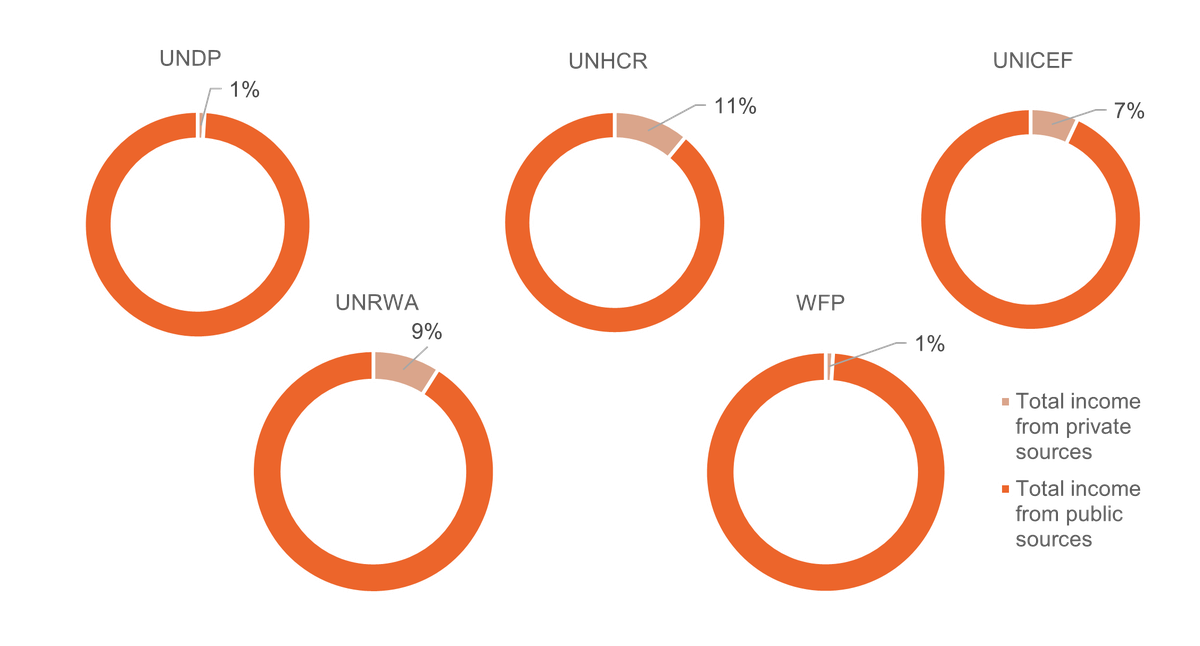

Figure 8: UNHCR, UNICEF and UNRWA rely more on funding from private donors than UNDP and WFP

Five doughnut (circle) percentage charts showing the proportion of private humanitarian to public humanitarian funding received by individual UN agencies (UNDP, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNRWA, WFP) to 2019.

| 2019 |

Total income from private

sources |

Total income from public sources |

|---|---|---|

| UNDP | 1% | 99% |

| UNHCR | 11% | 89% |

| UNICEF | 7% | 93% |

| UNRWA | 9% | 91% |

| WFP | 1% | 99% |

Source: Development Initiatives based on GHA's unique dataset of private contributions.

Notes: Data is in constant 2019 prices. Chart and analysis include data from five UN agencies that responded to our survey.

Where is private humanitarian funding spent?

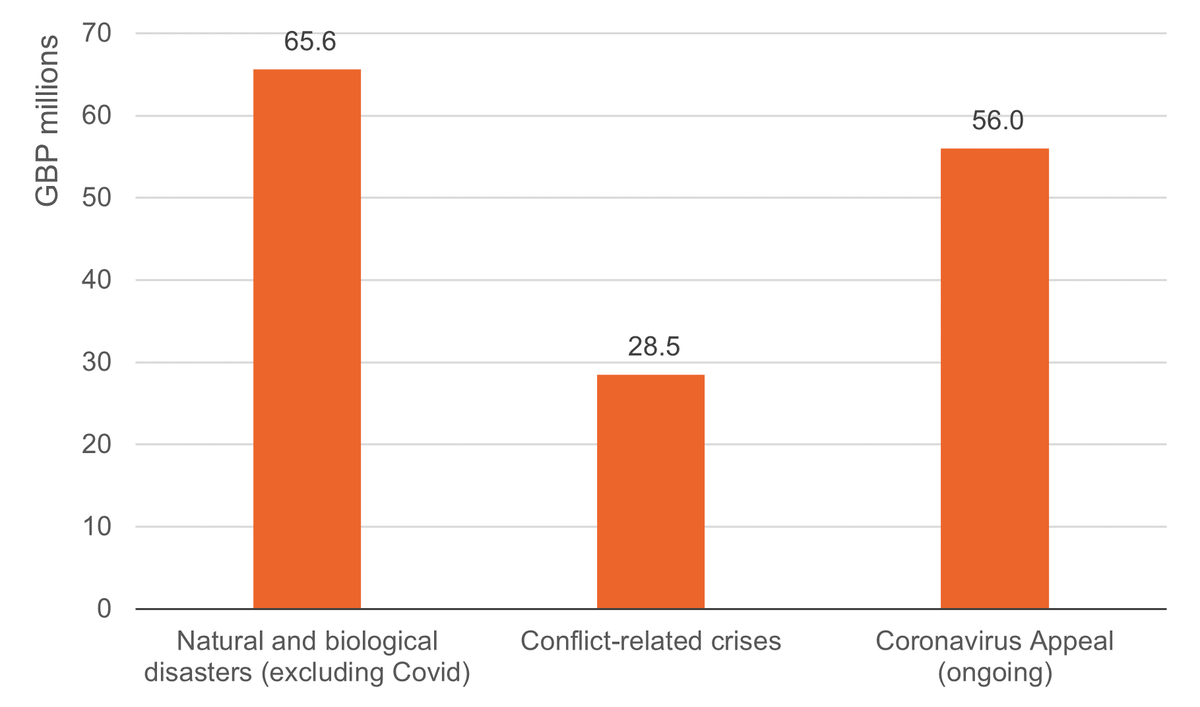

The evidence suggests that individual givers support rapid-onset natural disasters more generously than longer-term conflict-related crises. While not representative of all individual giving, evidence from the Disasters Emergency Committee (DEC), an umbrella group of 14 leading UK charities, shows that between 2000 and 2020, the average public response to DEC appeals concerning natural and biological disasters was more than double that to conflict-related appeals (see Figure 9). The largest public response for a natural disaster was for the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, which raised £392 million through the DEC appeal, while the largest DEC appeal response to a conflict-related crisis in the last two decades was £35 million for the 2004 Sudan Emergency Appeal. This has recently been superseded by DEC’s Ukraine appeal which has raised £100 million as of 7 March 2022. [5] Interviews with humanitarian organisations emphasised the role media coverage plays in determining the extent of the public’s support for a crisis.

Figure 9: Historically, natural disasters have received more support from individuals than conflict-related crises

Average total donations, per appeal, to Disasters Emergency Committee appeals, 2000–2020

A column chart showing the average total donations in GBP millions from 2000-2020 for natural and biological disasters (excluding Covid), conflict-related crises and the Covid appeal received by the Disasters Emergenct Committee appeals.

|

Crisis

Type |

Number of appeals | Total Raised (millions) |

Average appeal response

(millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Natural

and biological disasters (excluding Covid) |

13.0 | 853.0 | 65.6 |

| Conflict-related crises | 8.0 | 228.1 | 28.5 |

| Covid Appeal (ongoing) | 1.0 | 56.0 | 56.0 |

Source: Disasters Emergency Committee, 2021.

Notes: Natural and biological disasters include earthquake, drought, tsunami, cyclone, hurricane, flood, volcano eruption and epidemic.

Understanding the types of crises other private donors (such as philanthropic foundations and the private sector) support, and how this compares with public donors, is challenging given that funding flows from private actors are not comprehensively tracked in the same way as funding from public donors. From the data that is reported to UN OCHA’s FTS, the largest recipient of private humanitarian assistance in 2020 was Yemen (US$51 million) followed by Lebanon, which saw a fivefold increase in private funding following the Beirut Port blast.

Box 3

Data gaps in understanding private funding

Reliable and comprehensive data on humanitarian financing from public donors is well established through platforms such as FTS, the OCED DAC’s Creditor Reporting System and the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI). However, accessing comparable data for private donors remains challenging and there is currently no global mechanism for systematically tracking private international humanitarian and development flows.

Most funding flows from private sources are either entirely absent or only partially represented on FTS and the OECD Private Philanthropy for Development, and the total reported volume of private funding represents a fraction of the estimate that DI calculates through our data surveys to recipients of private funding. In total, between 2015 and 2020, only 7% of the private funds DI estimate through our annual research was reported to FTS. Tracking non-financial assistance from private donors is also a challenge. While FTS allows a funding flow to be marked as an in-kind donation, this is not consistently used by reporting agencies. [6] Additionally, some recipient organisations attempt to quantify and include in their accounting pro bono or in-kind assistance whereas other organisations do not. Initiatives such as the International Fundraising Leadership Forum peer review [7] provides a summary of global private fundraising trends from the largest UN agencies and INGOs, however it does not disaggregate between development and humanitarian funding and the data is often not made publicly available.

Traditional financial tracking platforms therefore tend to drastically underestimate the volume of private funding in the humanitarian system. To combat this, better routine reporting is needed from both private donors, such as foundations and corporations, and recipient organisations including the reporting of funding received from individuals which makes up the bulk of total private funding. Having consistent yearly data would create greater transparency around where private donor funds are spent and support a more coordinated response. It would also better reflect the contribution private donors make to humanitarian response. Despite this, there do not seem to be the incentives in place currently for donors and recipients to provide more detailed and comprehensive reporting to real-time platforms such as FTS and IATI. In part this is due to private funding not having the same accountability structures as funding from public donors.

Characteristics of private humanitarian assistance

Aspirations of the Grand Bargain [8] to increase not only the quantity of humanitarian funding, but also the efficiency and effectiveness of that funding, have partly focused on enhancing the quality of humanitarian funding provided by public donors. Characteristics of quality funding include reduced earmarking and multi-year funding. [9] The impacts of Covid-19 and the urgency of the response also reinforced efforts to institutionalise more flexible funding arrangements. [10] While defining, improving and monitoring flexible funding from public donors is the focus of much current policy debate, there is little information or scrutiny around the characteristics of funding from private donors. The following section attempts to identify the key characteristics of funding from different private donors, including the level of funding flexibility.

The following earmarking analysis is based on data received from 11 organisations. Organisations who regularly contribute to DI’s annual private funding survey were approached and data was received from three UN agencies, six INGOs and both IFRC and ICRC. While not representative, this sample of organisations represents over half (57%) of the total income from private sources in 2019 and provides a snapshot of private donor funding quality. Data was also requested on the proportion of funding from private donors which is provided within multi-year frameworks, however this is not something regularly monitored among the organisations who responded to our survey, and only five organisations were able to provide this information.

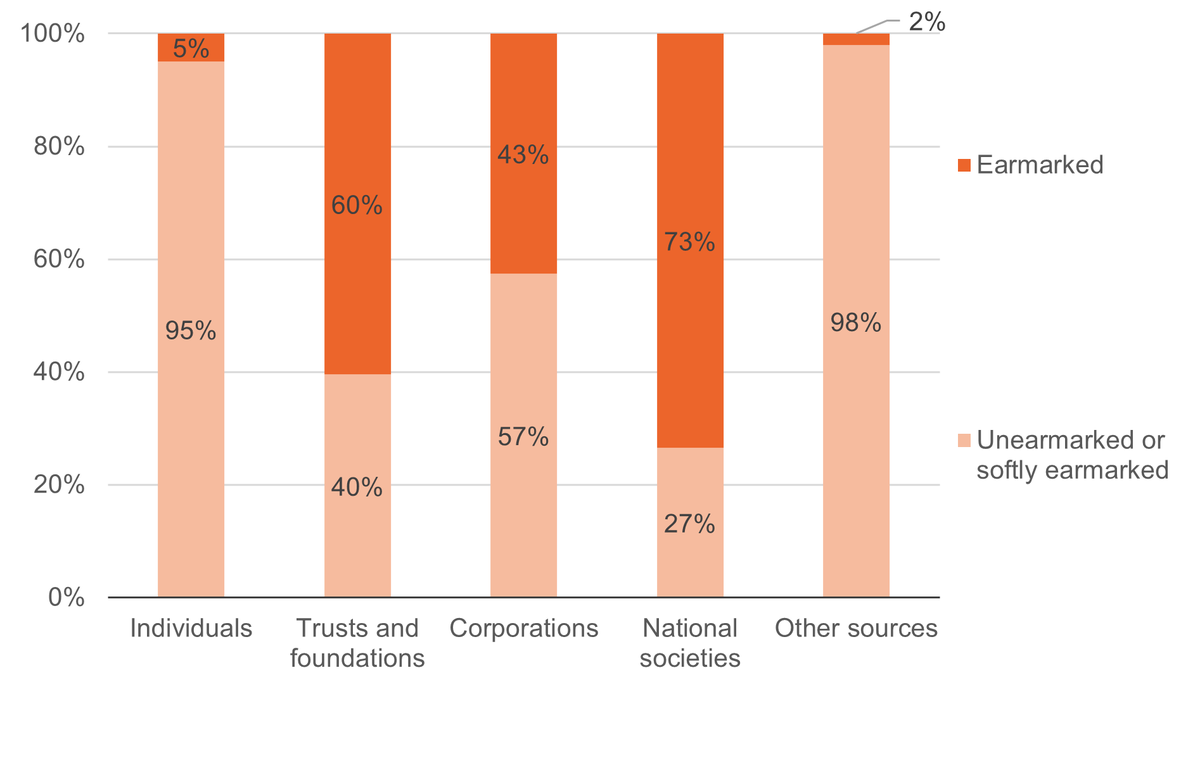

How flexible is funding from private donors?

Funding from private donors is notably more flexible than funding from public donors, in terms of the proportion that is unrestricted. Based on data from 11 recipient organisations, the overall proportion of private funding that is unearmarked or softly earmarked was 95% in 2019 with more than half (51%) of private funding to three UN agencies unearmarked or softly earmarked. As a comparison, data collected by DI in 2019 found that just 14% of total humanitarian funding (from both public and private donors) to UN agencies was unearmarked. Figure 10 shows that levels of earmarking varies between private donor type and is mainly driven by the high degree of flexibility in funding from individuals which makes up the largest donor group.

Figure 10: Private donors – especially individuals – provide more flexible funding than public donors

Proportion of unearmarked and softly earmarked funds by private donor type, 2019

A stacked column percentage chart showing the breakdown of earmarking for each of the five categories (individuals, trusts and foundations, corporations, national societies and other sources) in 2019.

| Individuals | Trusts and foundations | Corporations | National societies | Other sources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earmarked | 5% | 60% | 43% | 73% | 2% |

|

Unearmarked

or softly earmarked |

95% | 40% | 57% | 27% | 98% |

Source: Development Initiatives based on a sample of 11 organisations providing data bilaterally.

Notes: Data collected from six NGOs (ACF International, CAFOD, MSF, Caritas, Samaritan’s Purse, ZOA), three UN agencies (UNICEF, WFP, UNRWA) and two Red Cross Red Crescent organisations (ICRC and IFRC). This uses a more recent IFRC dataset received than in previous analyses on private funding.

Nearly all funding from individuals (95%) is unearmarked and can be used by the recipient as completely unrestricted funding, or softly earmarked, for example to a specific appeal. The vast majority of individual giving is also not restricted to a certain timeframe, or if donated to a specific appeal, valid within the lifespan of that crisis. National societies and committees also have a high degree of flexibility as the majority of funding is from individuals.

Income from individuals represents a valuable source of flexible, multi-year funding for recipient organisations. This type of funding allows an organisation to fund crises or projects that may be difficult to fundraise for through other channels, rather than being led by donor priorities. With this income organisations can plug funding gaps and reallocate and disburse funding quickly to sudden-onset emergencies. It can also allow organisations to set their own programming practices, rather than being subject to donor regulations, for instance in relation to the provision of overhead costs to partners. While public fundraising and maintaining levels of individual support is time intensive, funding from individuals has low administration costs compared to managing grants from other donors.

Trusts and foundations provide less earmarking flexibility in comparison with individuals, although 40% of funding was provided as unearmarked or softly earmarked in 2019. Interviewees emphasised the variation in funding flexibility between different philanthropic foundations, from foundations offering totally unrestricted funding with light-touch reporting requirements to foundations with grant management processes more akin to public donors. However, generally, funding from foundations is perceived to be more flexible than public donors with less intensive reporting requirements. Of the five organisations that were able to provide information on the length of grants from foundations, nearly all contributions were no longer than 24 months, though evidence from interviews suggest that most partnerships with foundations are long-term. Partnerships with foundations also vary; some foundations have well-defined strategic objectives and funding priorities that they are seeking to deliver against, whereas others have less experience in the humanitarian space and are happy to fund the general mandate of the recipient organisation. The characteristics of a quality partnership with foundations reported by recipients are the same as with public donors: [11] long-term relationships, productive dialogue, and flexibility in implementation in changing circumstances.

Like foundations, companies and corporations provided humanitarian assistance in a mixture of ways with just over half (57%) provided as unearmarked or softly earmarked in 2019. Funding from the private sector can vary from employee giving schemes to corporate social responsibility donations and grants. As well as providing financial assistance, some companies and corporations also provide non-financial or in-kind support to humanitarian organisations. Recipients emphasised that having a mixture of these different assistance types is the sign of a good corporate partnership.

Given the diversity among corporate donors, funding flexibility in terms of length of funding varies though, similar to foundations, the private sector is generally perceived to be more flexible and have lighter reporting requirements than public donors. The type of partnership between companies and corporations and recipient organisations also varies depending in part on the organisation’s agenda. Some private sector donors have clearly defined strategic priorities, for example within a certain sector or region which may be linked to their commercial operations, for others their philanthropic activity may be more led by staff priorities.

With different accountability structures to public donors, foundations and companies and corporations can be willing to fund projects that more traditional donors, such as public donors, may not. Some foundations see their added value as being able to take risks on innovative projects in order to build an evidence base that facilitates and incentivises the entry of public donors. Interviewees emphasised that this higher risk appetite means they can fund projects or initiatives through a private donor that they are not able to through a public donor. On the other hand, most private donors do not have the same experience and expertise in humanitarian action as public donors, and some interviewees reported that this can affect donor understanding of funding requirements, for example the need for funding flexibility to cover overheads. Developing partnerships with foundations and private sector organisations can be time consuming with high transaction costs, and recipients have to consider seriously whether they have the internal capacity to make most use of this kind of support.

Since the start of Covid-19, there is evidence that private donors have adapted quickly to increase flexibility and predictability of funding. As well as increasing financial contributions, an OECD report on the behaviour of private trusts and foundations in the immediate aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic found that foundations were increasing funding flexibility to grantees, supporting large-scale fundraising, and guaranteeing pay-outs. [12] A more recent survey by the Association of Charitable Foundations found that 84% of UK foundations would continue to offer the flexibility around reporting and payments that was introduced in 2020. [13] Some recipient organisation interviewees emphasised the strength of the private sector response to Covid-19, in part because some private sector companies see themselves as part of the solution.

Beyond financial assistance

Private donor support to humanitarian response goes beyond providing financial resources, especially at the local level where the private sector is a major stakeholder in humanitarian response. Increasingly, private sector donors are moving towards a ‘corporate partnership’ approach that encompasses a wide range of support, from financial and in-kind contributions to providing technical expertise to improve the internal operations of humanitarian organisations and providing direct support in crisis settings.

For some recipient organisations, non-financial assistance from the private sector makes up a small but important component of their private donor base. This could include in-kind donations such as software licenses and goods, and pro bono services such as legal advice and management consultancy. Pro bono assistance is seen as a way of accessing skills and expertise not normally available to recipient organisations or that donors are normally unwilling to fund.

Private sector actors have long been involved in rapid response contexts, especially national actors who may provide services and resources to support their local community affected by crisis. Increasingly there is a push toward providing humanitarian assistance through local markets where possible. Partnerships between multinational corporations and humanitarian actors have also introduced new forms of private sector engagement in various sectors, such as logistics and supply chain management, telecommunications and cash transfers. As crises become more complex, protracted and often increasingly in urban, middle-income contexts, private sector actors are seen as able to provide crucial competencies and skills that go beyond, and strengthen, humanitarian capacities. [14] An example of this is UNICEF’s partnership with standby partner the Veolia Foundation, the philanthropic arm of the global waste management organisation. In the immediate aftermath of the Beirut explosion, Veolia specialists were deployed to support UNICEF and its partners to assess damage and lead leakage detection works and coordinate the repair of water distribution networks in the city. [15] Beyond direct financial support, these non-financial partnerships can drive innovation and efficiencies in the humanitarian sector, often through use of new technologies. [16]

Beyond rapid response, private actors are also expanding their humanitarian work to encompass resilience and disaster risk reduction (DRR), particularly through the development of safety nets and micro-insurance initiatives. [17] For example, the R4 Rural Resilience Initiative was developed in 2011 by the multinational insurance company Swiss Re in partnership with Oxfam America and WFP to tackle climate risk. The initiative was originally established with philanthropic funding from the Swiss Re Foundation, before becoming a commercial enterprise, and sought to link community DRR with commercial financial tools by providing weather-indexed insurance to vulnerable rural households in Africa. [18]

While a focus of much research and policy debate, challenges remain in fully realising the potential impact of private sector engagement in humanitarian action. Various barriers exist, including issues around coordination and the limited opportunities for interaction and discussion between the private sector and humanitarian personnel, the focus on engagement at a fundraising level rather than at a technical level, partnerships being concentrated at a headquarters level and broader cultural issues around different ideologies and language. [19] A 2017 study into the perspectives of private sector actors in the humanitarian system, published by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, emphasises the need for shared tools and partnership models to guide principled business engagement.

Case Study

Pooling private sector expertise for humanitarian response

The Logistics Emergency Team (LET) comprises four global logistics and transportation corporations: UPS, Maersk, Agility and DP World. Through its partnership with WFP, the LET provides support to the Logistics Cluster and aims to bring together the capacity and resources of the logistics industry with the expertise of the humanitarian sector to provide more effective and efficient emergency relief. Since its creation in 2005 the LET has responded to 22 natural disasters. [20]

In the aftermath of the 2018 Sulawesi earthquake and tsunami, the LET was central in supporting the government-coordinated humanitarian response. Operational decisions were able to be expedited as a result of the LET’s information sharing, as well as its knowledge of local businesses and networks. For example, the LET provided the humanitarian community with information on the condition of the port in the affected area, which determined the type of vessels that could gain access in order to offload vital relief materials. [21]

The WFP/LET platform is a pioneering initiative in the coordination of the diverse set of actors involved in crisis contexts. [22] Further development of such integrated platforms is expected as crises become increasingly complex in nature and global in scale.

What next for private funding?

The need to better engage with new donors, including the private sector, has been referenced as a crucial strategy in plugging the humanitarian funding gap. Within the current context of accelerating humanitarian needs, the role of private actors as donors and partners in humanitarian assistance is only set to expand as the need to leverage additional forms of finance becomes more pressing. In particular, there is increasing interest in the potential of the private sector to unlock significant funding through innovative financial models.

Despite this, efforts to broaden the humanitarian finance base through previously untapped resources in the private sector have been slow. [23] Indeed, over the years total private humanitarian assistance has not grown as a proportion of total funding and individuals remain the largest source of private funding for humanitarian response. The push for a growth in corporate partnerships and business solutions to humanitarian issues, a key recommendation of the High-Level Panel on humanitarian financing, also raises the issue of how to most accurately account for and quantify these types of private sector contributions. While this briefing has sought to provide a top-line picture of current trends in private international humanitarian assistance, the lack of systematic reporting and publicly available data reduces overall transparency.

Better data on private funding, including what it is spent on and where, is needed to improve response coordination between agencies, public donors and governments and better identify where funding gaps remain. While private donors such as trusts and foundations are not subject to the same accountability structures as public donors, they are still accountable to the people and governments they are trying to assist. Based on this, there should be incentives for private institutional donors, and recipients, to publish funding data to real-time platforms such as FTS or IATI. This would address some of the outstanding data gaps and questions, for example, around which crises institutional private donors support, which countries provide the most in terms of private funding, the contribution of private donors within domestic crises, and the extent to which private donors play a role in empowering local and national actors through direct funding.

In part, better funding transparency could foster improved engagement and coordination between private donors and humanitarian actors. Beyond this, wider questions remain around the potential for private actors to support humanitarian response as donors, including:

- What are the incentives for different private actors to engage in humanitarian response?

- What barriers exist to increasing financial and non-financial private assistance?

- What are the challenges, both practical and political, in increasing engagement between the humanitarian and private sector?

- How could there be greater collaboration and understanding between private donors and humanitarian actors?

Acknowledgements

DI would like to think the various organisations who contributed to this briefing through providing data and through interviews: Acción contra el hambre, CAFOD, Caritas Switzerland, the Disasters Emergency Committee, ICRC, IFRC, the Ikea Foundation, Médecins Sans Frontières, Norwegian Refugee Council, Samaritan’s Purse, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNWRA, WFP and ZOA. DI would also like to thank the organisations who provide data every year for our GHA private funding survey.

Downloads

Notes

-

1

See OCHA Financial Tracking Service progress on appeals here: https://fts.unocha.org/ . Accessed on 1 February 2022.Return to source text

-

2

High-Level Panel on Humanitarian Financing Report to the Secretary-General, 2016. Too important to fail—addressing the humanitarian financing gap. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/%5BHLP%20Report%5D%20Too%20important%20to%20fail%E2%80%94addressing%20the%20humanitarian%20financing%20gap.pdfReturn to source text

-

3

The latest year for which private donor funding data is available is 2019 due to when the organisations' accounting systems close. Funding for 2020 is based on estimates and will be finalised in the 2022 Global Humanitarian Assistance report.Return to source text

-

4

The latest year for which private donor funding data is available is 2019 due to when the organisations' accounting systems close. Funding for 2020 is based on estimates and will be finalised in the 2022 Global Humanitarian Assistance report.Return to source text

-

5

Disasters Emergency Committee. Ukraine Humanitarian Appeal. Available at: https://www.dec.org.uk/appeal/ukraine-humanitarian-appeal . Accessed on 9 March 2022.Return to source text

Related content

Donors and recipients of humanitarian and wider crisis financing

Most of the largest donors increased funding but three, including the UK, made big cuts. Funding to the ten largest recipients for needs unrelated to Covid-19 fell by US$3 billion.

The power of transparency: Data is key to an effective crisis response

DI's Verity Outram and World Vision's Daniel Stevens share lessons, applicable to the coronavirus pandemic and more broadly, for how transparency and high-quality data can help humanitarian organisations, donors and advocates better respond to crises.