Supporting longer term development in crises at the nexus: Lessons from Somalia: Executive summary

Executive summary

DownloadsIntroduction

This Somalia country report contributes to a multi-country study [1] focusing on the role of development actors in addressing people’s longer term needs, risks and vulnerabilities and supporting operationalisation of the humanitarian–development–peace (HDP) nexus. This is pertinent to the Covid-19 response, involving both immediate lifesaving assistance and longer term support for health systems, socioeconomic impacts and peacebuilding. [2]

This report aims to improve understanding of how development actors operate in Somalia and their current and potential role in addressing the longer term needs, risks and vulnerabilities of crisis-affected populations. It explores the extent to which development actors work alongside or in complementarity with humanitarian and peace actors at the strategic, programmatic and institutional levels. It identifies examples of good practice, lessons and recommendations for how development assistance can better prevent and respond to crisis situations and support the delivery of the HDP nexus agenda, both within Somalia and globally. This report is based on desk research and key informant interviews with actors working in Somalia at local, national and international levels.

This study is part of Development Initiatives’ programme of work on the nexus and aligns with objectives of the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Results Group 5 on Humanitarian Financing. It builds on 2019 research on donor approaches to the nexus [3] and the IASC’s research on financing the nexus, [4] which identified a gap in understanding how development finance actors address longer term development needs of vulnerable populations and structural causes of crises. Other focus countries are Cameroon and Bangladesh, and the study will conclude with a synthesis report with key findings and lessons across countries and recommendations for development actors engaging in crisis contexts.

This study will build the evidence base for how development actors work in crisis contexts, informing national and global development policy and decision-making and supporting effective programming approaches. Development Initiatives, with support from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) under the umbrella of IASC Results Group, will engage with development actors on the findings of this research.

Slow progress in a situation of protracted and recurring crisis

Somalia is an interesting case for this study as it has for the past 30 years experienced political instability and frequent conflict, coupled with environmental, disease and economic shocks, converging in 2020 into a triple threat of flooding, desert locusts and Covid-19. These crises have resulted in widespread internal displacement, sustained food insecurity with recurring spikes and high levels of poverty, emphasising the need for preventative and longer term approaches. The international community has supported reconciliation and state-building efforts, aimed at achieving a political settlement among competing political/clan elites and establishing legitimate federal and state governance institutions. While substantial progress has been made in forming federal and state institutions, international agencies and remittances continue to play a major role in the delivery of basic services.

The successful intervention of the humanitarian sector in averting famine after prolonged drought in 2016 and 2017 fostered greater acknowledgement that humanitarian assistance alone cannot provide a sustainable or cost-effective solution to recurring shocks in Somalia. Donors and the UN community recognise that development efforts should be increased to prevent and build resilience to future economic, climate and conflict-related shocks. Donors are investing in longer term forecasting, anticipatory action, risk reduction and resilience, and, more recently, in recovery, safety nets and social cohesion, but more is needed to move towards sustainable and lasting solutions. This requires substantial development investment and strengthened synergies between humanitarian, development and peace actors.

The Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) has low domestic revenue and public spending per capita compared with other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, and it faces significant challenges in increasing tax revenue. Domestic spending is dominated by administrative and recurring costs, such as public sector salaries and operational costs (including security), with little left for the social sector. Somalia has received steadily growing volumes of official development assistance (ODA) over the past decade, and in March 2020 Somalia achieved the milestone of reaching the ‘decision point’ of the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative, restoring access to regular concessional financing and bringing the country closer to debt relief.

Recommendations

Strategy and partnerships

There should be a focus on building federal and state government capacity for service delivery

In recent years there has been a strategic shift in the engagement of international actors to address underlying and structural causes of crisis, although opportunities for this vary across the country. Development partners are scoping opportunities to work with and through government systems as capacities and trust is developed and, in areas where this is not yet possible due to the absence of structures and relationships, scoping opportunities and laying foundations for this in the future.

The World Bank Multi-Partner Fund (MPF) has been testing and incrementally expanding finance through government systems, in parallel with technical support to strengthen public financial management systems and develop a mutual accountability framework. The use of pooled resources to scale up budget support, linked with performance-based benchmarks, monitoring and accountability mechanisms, is expected to increase substantially. This should be done cautiously to manage the risks not only of corruption and misuse of resources but also of conflict, such as the potential to create political competition over aid resources or contribute to inequalities that lead to grievances.

For development assistance to play a greater role in meeting the needs of crisis-affected populations, development partners need to ensure they have partnerships and dialogue with governments to prioritise service delivery, social protection systems, livelihoods, economic development initiatives aimed at expanding the government’s fiscal base, and other interventions necessary to achieve medium- to long-term solutions to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and target groups experiencing vulnerability. For example, the World Bank’s Country Partnership Framework (2019–2022) prioritises strengthening institutional capacity for service delivery and restoring economic resilience as its two focus areas, and the EU prioritises governance and security, food security and resilience, and education as the focus areas of its 2014–2020 National Indicative Programme. It will be important for Somalia’s major bilateral and multilateral partners to sustain policy dialogue with the FGS and federal member states on reforms to strengthen government-led service delivery and social protection systems (such as the World Bank’s dialogue with the FGS on the development of a social registry) and include benchmarks on social outcomes in accountability frameworks and country partnership frameworks. It will also be crucial to ensure a conflict lens is integrated into this dialogue and to ensure donor non-crisis financing to infrastructure and economic development is conflict sensitive. The establishment of Somalia’s federal structure is an opportunity for development partners to expand technical and financial support to government-led service delivery at the state and municipality level, although it will be important to navigate uncertainties and political tensions around the functions of each level of government.

Local responses should be scaled up through financing and capacity building for Somali NGOs, with private sector actors

Local and national NGOs are well-established in Somalia, having played a key role in the humanitarian response since the drought in 2011 and in advocacy on the localisation agenda. The establishment of NGO consortia on resilience and durable solutions to displacement also signals progress. Change is needed, however, in how donors approach and finance partnerships with local NGOs, and Somali NGOs should be included in consortia from the outset and involved in decision-making and management structures. Donors should consider scaling up direct funding to Somali NGOs (in line with World Humanitarian Summit commitments on localisation) through pooled development funds. Strengthening third-party monitoring structures and establishing a national NGO office and code of conduct would help to manage associated risks.

Coordination, planning and prioritisation

Organisational change should take place to deliver the nexus, not just informal collaboration

UN agencies and NGOs with mandates encompassing humanitarian and development work were better able to coordinate and adapt programming to address both immediate needs and longer term issues than those with a limited mandate. Some donors and agencies have internal divisions between their humanitarian and development teams, however, with limited systematic internal cooperation. A fundamental review of organisational structures is required in some cases to facilitate collaboration, coherence, and complementarity between HDP actors. Development partners might consider reorganising management structures, strategy and planning processes, and allocation decisions around regional, country or subnational geographic areas – rather than humanitarian, development and political functions – to strengthen coherence of their overall support. Strong leadership will be needed for this to occur.

Existing coordination mechanisms and development plans should be better aligned and built on as the basis for identifying shared outcomes and strengthening coordination among HDP actors

Somalia has an elaborate aid architecture, in which humanitarian and development actors have separate structures for coordinating among themselves and with government. While there are some examples of coordination across the HDP nexus, this is not systematic. There are multiple coordination platofrms at the federal, member state and district levels, which could be better aligned and inclusive of actors that are currently not well represented (such as peacebuilding and private sector actors). Regular joint analysis, drawing together expertise from across the HDP nexus, is not yet the norm, although the latest UN Common Country Analysis is considered a good example.

Given the complexity of existing coordination mechanisms, there is little appetite in country to establish a new standalone nexus coordination structure. Ideally, existing coordination mechanisms and development panning processes should be built on to better link up HDP actors around joint analysis, planning and implementation of collective outcomes. The UN has taken the lead on nexus coordination and planning and collective outcomes initiatives, and there is limited engagement and ownership by the government and key development actors, including international financial institutions (IFIs). While four collective outcomes were agreed by a group of humanitarian and development actors in 2018, the extent of buy-in among non-UN actors for their implementation is unclear and there is a lack of ownership by development actors.

For nexus collaboration to be effective, leadership and buy-in is required from both development and humanitarian actors, with government. The UN and World Bank should play such a role, formally leading strategic nexus coordination and planning and shared outcomes initiatives, in line with the IASC Light Guidance on Collective Outcomes, [5] jointly with government counterparts. Coordination should go beyond UN actors and be as inclusive as possible while still functioning effectively.

The Somalia National Development Plan 2020 to 2024 (NDP9) [6] and accompanying cooperation frameworks could provide a strong basis for coordination between government and all international actors, but they are currently more effective at coordinating development and security actors and have not managed to bring together the full range of HDP actors. The new aid architecture under NDP9 is starting to be operationalised and provides the foundation for the recently signed UN Cooperation Framework. Therefore, the new nexus-coordination mechanism proposed by the UN should seek to complement and support these nationally led coordination efforts.

There has been strengthened coordination of development and humanitarian actors working on health as a result of the Covid-19 response. This success could be built on across sectors, and area-based programming models that are strengthening coordination at local levels could be scaled up. Sub-national HDP coordination mechanisms could be established with the involvement of government, depending on the context.

At both national and sub-national levels it is, however, vital to maintain separation of humanitarian coordination and the independence of the Humanitarian Country Team. This is particularly important for assistance to states where conflict is active, areas are controlled by non-state armed groups, and where coherence is not an option, both practically and to safeguard humanitarian principles. In certain circumstances, the humanitarian sector’s duty to respect the humanitarian principles of neutrality and independence in order to access people in need must take precedence over greater collaboration across the HDP nexus. Establishing mechanisms that bring together HDP actors should therefore complement and not replace separate humanitarian coordination mechanisms.

Donors should reconsider funding and system requirements to provide greater incentives to work collaboratively across the humanitarian, development and peace sectors

Entrenched ways of working and a lack of incentives to collaborate across the humanitarian, development and peace sectors can be a barrier to implementing nexus approaches in practice. Funding is a powerful incentive, and donors should create an environment conducive to collaboration and innovation. Channelling greater volumes of funding through joint programmes or pooled funds can help, as can sharing clear expectations on nexus commitments with all recipients of core and programme funding and supporting partners’ staffing capacities. Flexible funding is key to allow partners the space to iterate and innovate, but at the same time clear requirements and accountability to ensure that partners will make connections within and between themselves are needed. [7] Donors should explore how this can be built into contracts without restricting partners or adding to reporting burdens.

Consensus should be sought on the opportunities and limits to collaboration in stabilisation or active conflict settings

As with other countries, the most challenging aspect of the nexus in Somalia is understanding how peace and humanitarian components align. While humanitarian actors have begun to integrate social cohesion or peace components into their programmes, there are clear limits on how humanitarian action can or should be joined up with development or peace initiatives that have clear political or security objectives, particularly in areas of active conflict or where counter-terrorism or stabilisation efforts are underway. Dialogue is needed between actors on the opportunities, limits and principles for coordination, and, as a minimum, systems for communication and information-sharing should be strengthened.

The government should be supported to establish a shared data system on vulnerability and poverty that embeds tools for inclusive monitoring and evaluation; however, this should not replace independent humanitarian assessments and data

International actors should support the government to develop national data systems on disaster management, recovery and social protection to inform sustainable and collaborative responses to immediate and longer term needs of crisis-affected populations, and transparent standards for data management. Efforts are underway in this respect, including the Somalia Aid Management Information System, managed by the Ministry of Planning, Investment and Economic Development (MoPIED). Data systems currently managed by international actors (such as the FAO’s Early Warning Dashboard and the Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit (FSNAU)) should be embedded into these national data frameworks in the medium to long term, coupled with related investment in government institutional capacity development.

Joined-up data and assessments are often necessary for collaborative programming and are appropriate in areas such where government structures are strong. In other areas, independent assessments and protection of humanitarian data is vital for safeguarding humanitarian principles, and in these contexts information-sharing and complementarity may be possible where collaborative programming is not. Appropriate joining up of assessments and programming is thus highly context specific and varies across Somalia.

Programming approaches

Community-level resilience and peacebuilding approaches should be scaled up and run in parallel to longer term national efforts

Humanitarian agencies have developed innovative resilience programmes over recent years, making significant yet small scale progress at the community level. There have also been positive examples of collaboration across sectors in the disaster risk reduction space. For greater impact and wider reach, these efforts should be scaled up based on learnings from successful programmes. In the longer term, resilience approaches should be embedded more holistically into national efforts to address structural sources of vulnerability and poverty, including national frameworks for shock-responsive safety nets, social protection and livelihoods. This will require greater development investments in what has traditionally been a humanitarian-led resilience agenda in Somalia, although the need for parallel complementary humanitarian and development-led programmes will continue in the medium-term. This will also depend on a range of sub-national contextual factors including the capacity of and trust in local government structures, the local conflict context and access. Community-based peacebuilding and conflict-sensitive recovery approaches should also be scaled up and run in parallel to longer term national efforts. Donors interviewed highlighted the need for resilience to be embedded more holistically within national priorities on safety nets, social protection, food systems and livelihoods.

Durable solutions programming should increasingly be led by development actors

Much progress has been made on the durable solutions agenda for internally displaced people in Somalia (see definition in Box 1 ), including buy-in from the government. Humanitarian actors have largely led programming in this area, but there is a need to transition leadership and reporting lines to government and include a broader range of development actors. Optimising development finance and private sector engagement for this purpose will be key.

Financing tools

The Somalia Development and Reconstruction Facility and multi-partner funds should be reviewed and reinvigorated as mechanisms to enhance coordinated and flexible financing

The 2013 Somali Compact, based on the New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States, established the Somalia Development and Reconstruction Facility (SDRF) as a mechanism to enhance donor coordination and country ownership. The SDRF aimed to address the legacy of fragmented and project-based aid by providing a common governance framework for three aligned trust funds set up to pool donor contributions: the UN Multi-Partner Trust Fund (UN MPTF), the World Bank Multi-Partner Fund (MPF) and the African Development Bank’s multi-partner Somali Infrastructure Fund (SIF). The SDRF was initially slow to operationalise; for example, the SIF only became operational in 2016 and the first mutual accountability framework was endorsed in 2017 (although the peacebuilding and state-building goals under the New Deal were in place prior to this).

Although the SDRF now operates at a larger scale, its full potential is not yet used. The aid landscape in Somalia remains fragmented and donors continue to channel most of their support bilaterally and outside of government systems. Donor confidence in the UN MPTF has waned for a variety of reasons, including high overhead costs, inflexibility and challenges related to delivery by UN agencies. The World Bank MPF, which was set up to strengthen delivery through government systems, has made incremental progress and is looking towards working at a greater scale. While much smaller, the Somalia Stability Fund offers an example of an agile, flexible and context-driven pooled fund that could potentially be built on. To enable trust funds to provide funding flexibility, there is a need to protect funds from earmarking in alignment to donors’ own political ambitions. One option would be to agree a vulnerability criterion for allocation of trust funds. Another option could be to ring fence a flexible funding window for partners within the trust funds. Further decentralising the management of these funds through nationally situated and staffed mechanisms would enable greater alignment to local needs, understanding of the context and flexibility.

Flexibility and contingency financing should be embedded into development programmes

There are examples from donors, the UN and the FGS of budget flexibility and contingency financing being built into programmes to respond to unforeseen, a scale-up in existing, or rapid-onset crises. Contingency mechanisms are vital for enabling a timely response to crises but are not yet systematised across development actors, with most progress to date in humanitarian contingency financing. Contingency financing mechanisms should be part of standard practice in the planning phase of development programmes. A high degree of budget flexibility is needed to re-allocate funds to respond to changing needs, with decentralised authorisation, reduced earmarking and less budget demarcation between HDP responses. Shock-responsive mechanisms should continue to be embedded into national safety nets and social protection programmes to allow them to be scaled up in response to cyclical environmental shocks. There is also scope to embed contingency financing mechanisms into country partnership frameworks that are agreed between major development partners and developing country governments and focus predominantly on structural and economic reforms. This could help strengthen access to contingency risk and crisis finance mechanisms at the national level to complement and better connect country-level strategy with global decision-making associated with dedicated global crisis financing modalities.

Donors should review and capture learnings from the Covid-19 response and how the speed and scale of response, risk and due diligence are balanced in future financing. Donors should also provide flexible funding to respond to Covid-19 and food insecurity issues while addressing long-term socioeconomic impacts and chronic displacement.

Strengthen evidence on the impact and comparative advantage of global crisis financing mechanisms

The World Bank and other development finance institutions, notably the African Development Bank (AfDB) in response to Covid-19, have established a range of global crisis financing modalities that are now benefiting Somalia. As of 2020, Somalia met the requirements for accessing the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA) Crisis Response Window, which is funding the Somalia Crisis Recovery Project and the Emergency Locust Response Programme.

While partners receiving these global funds are extremely positive about their added value, there are questions regarding the impact of these crisis financing modalities, specifically on vulnerable populations, highlighting the need for greater evidence on lessons for broader uptake. The World Bank, UN, AfDB and partners should consider ways to document and share publicly evidence of impact. For stronger alignment with local needs, contextual relevance and local ownership, decentralising the management of these global funds to regional and national levels should be considered. For this, senior analytical capacity on conflict and resilience and the appointment of senior staff with decision-making autonomy at country level will be key.

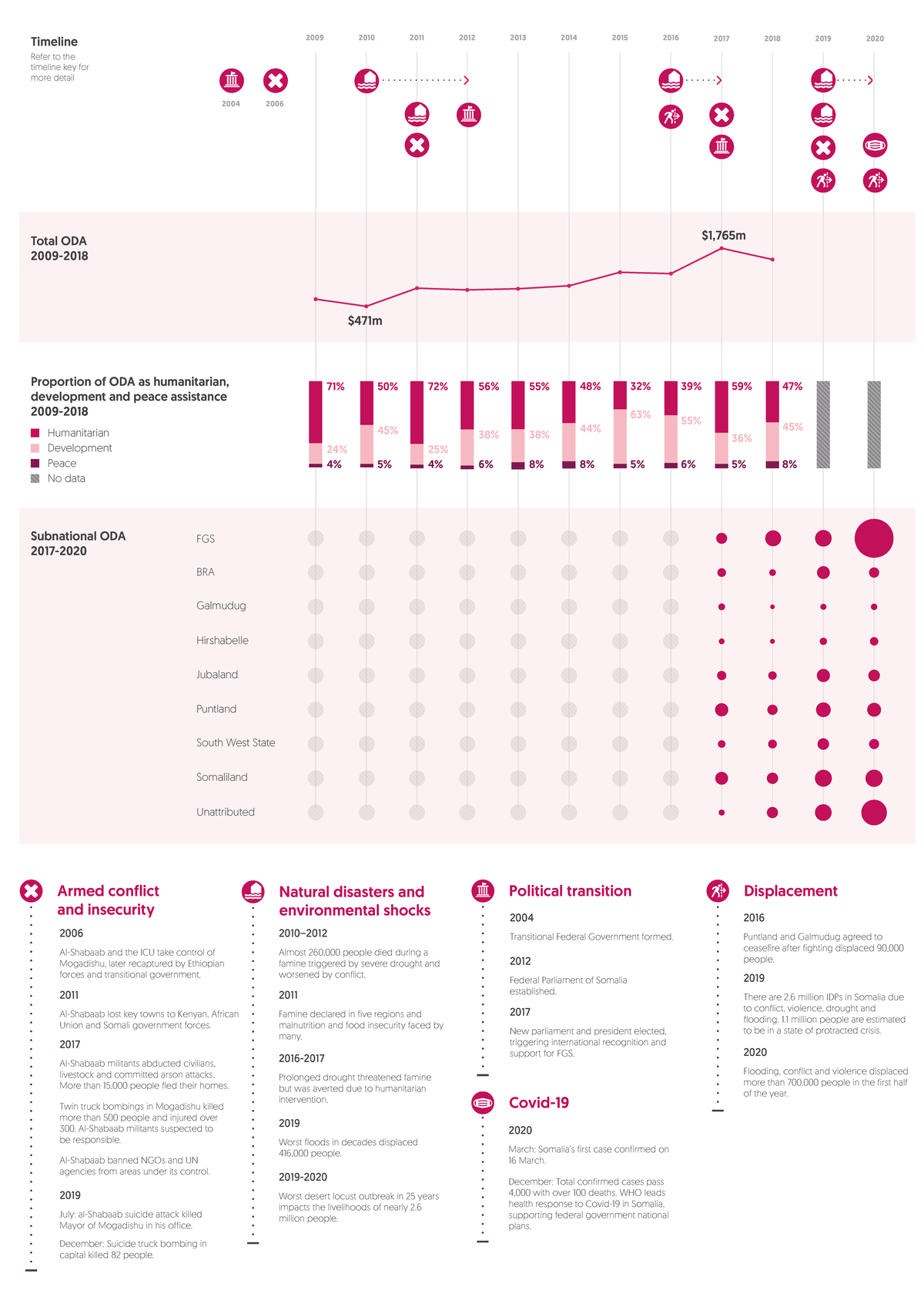

Our executive summary infographic below takes a look at key events in Somalia, plots total and regional distribution of official development assistance (ODA) annually between 2009 and 2018, and shows the proportion of ODA as humanitarian, development and peace assistance.

Map showing levels of food insecurity, poverty and displacement by region in Somalia, with the highest number of displaced people in need in the north west region (1.6 million), followed by South West State (1.1 million) and Jubaland (723,111). The highest level of food insecurity was in north west (716,000 people in IPC Phase3+) and in South West State (468,000 people in IPC Phase3+). 90.5% of households in Banadir region were within the poorest 20% (P20) in Somalia, as were 84.0% of households in north west.

Source: Development Initiatives based on the UN OCHA 2020 Humanitarian Needs Overview for Somalia (2019), IPC Acute Food Insecurity Classification, Somali High Frequency Survey (2017) and IMF World Economic Outlook (2020).

Notes: Humanitarian Needs Overview data on refugees and asylum-seekers, IDPs and total people in need are as of December 2019. Total displaced people do not include returnees. IPC Phase 3 and above figures are projections for October to December 2019 and include people experiencing acute food and livelihood crisis, humanitarian emergencies or famine and humanitarian catastrophe. 85.5% of people in IDP settlements are within the poorest 20% of people (P20) in Somalia, as are 84.5% of people in nomadic populations. The geographical regions include the following administrative regions: Benadir (Mogadishu), Jubaland (Gebo, Lower Juba, Middle Juba), central (Hiraan, Middle Shabelle, Galgaduud), north east (Bari, Mudug, Nugaal), north west (Awdal, Sanaag, Sool, Togdheer, Woqooyi) and South West State (Bay, Bakool and lower Shabelle). IDP = internally displaced people; IMF = International Monetary Fund; IPC = Integrated Food Security Phase Classification; P20 = people in the poorest 20%; UN OCHA = UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

Notes

-

1

Development Initiatives, with support from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), is leading the wider policy study under the umbrella of the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Results Group 5 (on Humanitarian Financing). The other focus countries are Cameroon and Bangladesh.Return to source text

-

2

Dalrymple, S., Looking at the coronavirus crisis through the nexus lens – what needs to be done. Development Initiatives, [web blog], 8 April 2020, www.devinit.org/blog/looking-at-the-coronavirus-crisisthrough- the-nexus-lens-what-needs-to-be-done/ [accessed 2 January 2021].Return to source text

-

3

Development Initiatives, 2019. Donors at the triple nexus: lessons from the United Kingdom. Available at: www.devinit.org/resources/donors-triple-nexus-lessons-united-kingdom/ and Development Initiatives, 2019. Donors at the triple nexus: Lessons from Sweden. Available at: www.devinit.org/resources/donors-triplenexus- lessons-sweden/ (accessed 4 January 2021)Return to source text

-

4

IASC, 2019. Financing the nexus: Gaps and opportunities from a field perspective. Available at: www.nrc.no/resources/reports/financing-the-nexus-gaps-and-opportunities-from-a-field-perspective/ (accessed 4 January 2021)Return to source text

-

5

IASC, 2020. Light Guidance on Collective Outcomes. Available at: www.interagencystandingcommittee.org/inter-agency-standing-committee/un-iasc-light-guidance-collective-outcomes (accessed 4 January 2021)Return to source text