Tracking cash and voucher assistance

In this report DI provides a comprehensive and unique assessment of the state of tracking cash and voucher assistance (CVA) used during humanitarian crises.

DownloadsIntroduction and summary

The commitment of the humanitarian community to increase its use of cash and voucher assistance (CVA) is seen as a success story of the Grand Bargain. [1] Progress has also been made through the Grand Bargain 2.0 in endorsing a new cash coordination model. [2] However, the most recent independent Grand Bargain monitoring report pointed out that the ‘tracking of the funding for CVA is still not optimal’. [3] Effective coordination of humanitarian CVA under the new model is hindered by a lack of timely and disaggregated data on where, by whom, how and for what CVA is used. This research therefore seeks to answer three main questions on the tracking of humanitarian CVA:

- What does the most recent, publicly available data on CVA tell us about its use in humanitarian crisis responses?

- How is data on CVA currently reported and made accessible through interagency reporting platforms?

- How can reporting of CVA be improved?

Firstly, the report analyses the global volume of humanitarian CVA, finding that it has increased in 2021, for the sixth consecutive year, to US$5.4 billion in transfers to recipients, but that the pace of growth has slowed . These global volumes do not include most cash transfers provided through government-led social protection systems in response to crises, though a clearer picture on this assistance is emerging in some contexts. UN agencies continued to be the largest implementers of CVA that year at 61% of the global total volume, followed by NGOs and the Red Cross and Red Crescent (RCRC) Movement at 22% and 18% respectively. Three quarters of CVA transfers to recipients globally in 2021 were in the form of cash , up from 69% in 2017, and one quarter as vouchers, with early 2022 data indicating that a further shift towards cash is underway.

The relative importance of CVA within overall humanitarian responses differs between crisis settings based on data from humanitarian response planning in 2022. The large multi-purpose cash response in Ukraine in 2022 is likely to drive a continued increase in global volumes of CVA. The share of CVA activities within five out of six clusters (with that share being at least 10%) across 18 response plans also increased between 2021 and 2022. Meanwhile project data from humanitarian response plans provides evidence for the concentration of humanitarian CVA with international, rather than local and national, agencies. International agencies accounted for 97% of requirements for CVA activities in 2022. Within those response plans, CVA projects are more likely to receive funding than other projects, but this trend is much more pronounced for international actors than it is for local and national actors. Project and funding data on 2021 shows that projects with CVA components by international actors were more than twice as likely as other projects to be funded. In comparison local and national NGOs (L/NNGOs) were only 7% more likely to receive funding for their CVA projects than for their other projects that year. This raises the question of to what extent there exists a tension between the commitments to increase the use of CVA and to localise humanitarian funding.

Secondly, the report examines the data availability on humanitarian CVA. It evaluates interagency reporting at the global and response level against the minimum reporting requirements agreed by the Grand Bargain cash workstream in 2020. The criteria are whether CVA data is available on transfer values, disaggregated by cash and vouchers and whether it shows sectoral objectives. The largest volume of comparable, public data is available on the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)’s Projects Module. It provides granular data on the planned size of CVA project components for projectised response plans, which reflect around a third of the humanitarian system. It is possible to match funding with project data, but this might be inaccurate if changes in the context required implementation of CVA to deviate from project plans. The International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) standard has the technical capabilities in place to fulfil all the minimum reporting requirements on CVA, but to date very little data has been published. More granular data on CVA is often available at the response level through efforts by cash working groups, though rarely in real time or with access to the underlying data. There also seems to be a missing link that brings together at the global level comparable data from these country-specific monitoring efforts.

To that end the report proposes the following key recommendations to improve the public data landscape on humanitarian CVA and thereby facilitate more effective coordination:

- The global Cash Advisory Group should agree on who is responsible for tracking CVA within the new cash coordination model. Data should be captured in line with the agreed minimum reporting requirements and regularly be incorporated into global, interagency reporting systems.

- Humanitarian agencies that participate in projectised response plans should ensure accurate and up-to-date information on CVA components of their projects are reported to the Projects Module and that all received funding is reported with project information.

- Organisations implementing CVA and publishing data to IATI should report on CVA transfer values as expenditure under their activities.

Insights from CVA data

What are the global trends in CVA in terms of volumes, implementing agencies and the use of cash or vouchers?

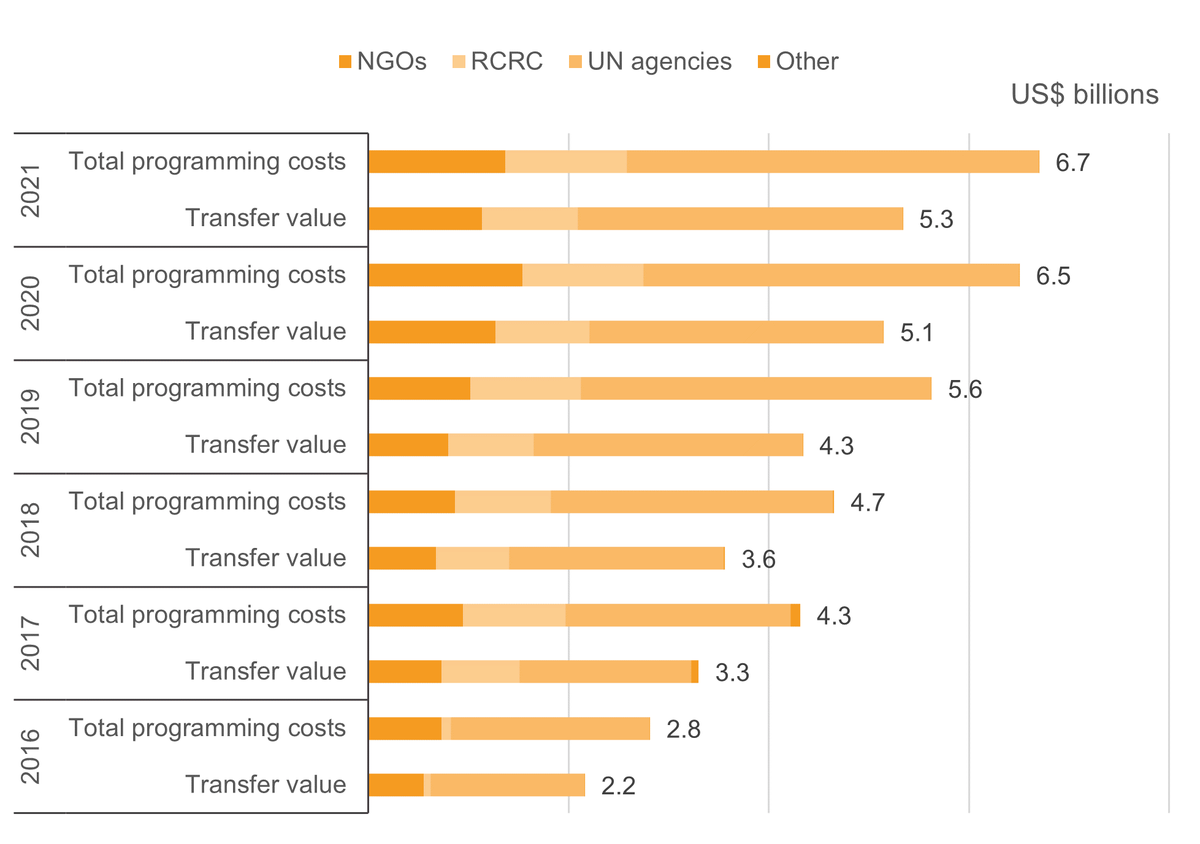

Global volumes of humanitarian CVA increased in 2021 for the sixth consecutive year, though the pace of growth has slowed. This is based on data largely collected directly by Development Initiatives (DI) and the CALP Network from humanitarian agencies implementing CVA (see Appendix 1 for more detail on the methodology). The global volume of CVA transfers to recipients grew by 4% in 2021 to US$5.4 billion, which is significantly less than the 19% increase in 2020. Including associated programming costs, the global volume of humanitarian CVA reached an estimated US$6.7 billion in 2021 ( Figure 1 ). Multiple organisations reported through the surveys that in 2021 they consolidated their CVA portfolios to ensure the quality of programming following large increases during the Covid-19 pandemic response. The slowing growth in humanitarian CVA meant that its share of total international humanitarian assistance (IHA) remained at 19%, similar to previous years. Assessments of the global share of CVA out of IHA remain estimates as they rely on collecting data from implementing agencies and also given the continuing lack of publicly available data connecting funding provided by donors and the delivery modality implemented by agencies ( Box 1 ).

The global volumes in Figure 1 do not include most cash transfers provided through government-led social protection systems in response to crises, though a clearer picture on this assistance is emerging in some contexts. There are conceptual and practical challenges to gaining a more comprehensive understanding of humanitarian CVA transfer volumes through social protection systems. These challenges include the lack of a shared understanding of what the parameters are to categorise cash-based social assistance as ‘humanitarian’. The availability of data on transfer volumes to crisis-affected populations through social protection systems also varies depending on the context. The Pakistan 2022 Response Plan is an example of how better data on social assistance in response to crises can inform response priorities. [4] In Pakistan – at the time of writing – the government has to date already disbursed more than US$131 million to over 1.2 million flood-affected families, [5] which is more than double of international humanitarian funding received by the response plan so far. [6] The food security cluster in Pakistan therefore focuses its response activities on actions that are complementary to the large-scale provision of cash by the government, for example by ensuring access to food and supporting the restoration of livelihoods. This underscores the importance of tracking social assistance in crisis contexts according to clear criteria that can inform donors how to support crisis-affected populations through existing response mechanisms, and that can help humanitarians agencies implement a complementary response.

UN agencies continued to be the largest implementers of humanitarian CVA in 2021, accounting for 61% of global total transfers to recipients. NGOs and the RCRC Movement maintained similar volumes in their CVA transfers to recipients in 2021 as in the previous year, making up 22% and 18% of total global volumes respectively. UN agencies experienced the largest increase in 2021 of the three organisation types, driven by a 43% increase in humanitarian CVA transfers for UNICEF, which reached US$351 million. [7] In 2021, the World Food Programme (WFP) continued to grow what already was the largest humanitarian CVA portfolio within a single agency, increasing CVA by US$194 million (up 9%) to US$2.3 billion. [8]

Figure 1: Global volumes of humanitarian CVA increase for the sixth consecutive year

Total funding for humanitarian cash and voucher assistance, 2016–2021

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer value | Total programming costs | Transfer value | Total programming costs | Transfer value | Total programming costs | Transfer value | Total programming costs | Transfer value | Total programming costs | Transfer value | Total programming costs | |

| NGOs | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| RCRC | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| UN agencies | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 4.1 |

| Other | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 2.2 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 5.6 | 5.1 | 6.5 | 5.3 | 6.7 |

Source: Development Initiatives (DI) based on data collected with the help of the CALP Network from implementing partners and on UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Financial Tracking Service (FTS) data.

Notes: NGO = non-governmental organisation. RCRC = Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. Data for 2021 is preliminary, as data for some organisations is based on estimations. Double counting of cash and voucher assistance (CVA) programmes sub-granted from one implementing partner to another is avoided where data on this is available. Programming costs are estimates for organisations that provided only the amount transferred to recipients. Data is not available for all included organisations across all years. For instance, the RCRC started to systematically track CVA only in 2017.

Three quarters of CVA transfers to recipients continued to be in the form of cash in 2021 and early 2022 data indicates that a further shift towards cash might be underway. In 2017, 69% of total CVA was transferred as cash to recipients. Survey responses collected by DI and the CALP Network also indicate greater attention by organisations to track the use of cash and voucher assistance internally, in line with the minimum reporting requirements on CVA (see section ‘The state of tracking humanitarian cash and voucher assistance’ below). In 2021, 86% of respondents were able to provide data disaggregated by cash and vouchers, compared with 73% in 2020 and only 54% in 2017, the first year this data was requested. In terms of cash and voucher use in 2022, early WFP data and planning information from projects across 16 response plans give an indication of early trends. The WFP dashboard on CVA data shows that as of 11 August 2022 cash transfers have made up 64% of its CVA portfolio, compared with 54% in 2020 and 57% in 2021. If WFP’s current split between cash and vouchers stays roughly the same, this will likely tip the global balance further towards cash assistance. Project information from 16 response plans with disaggregated data on funding requirements for cash and voucher project components in 2021 and 2022 [9] reveals a similar trend towards cash. The aggregate requirements for cash components out of total requirements for CVA projects for those plans increased by three percentage points to 64% in 2022.

However, overall this shift towards cash rather than vouchers is not seen consistently across individual response plans. A closer look at the country-specific data shows seven response plans remaining stable or increasing in their relative planned use of cash and nine shifting more towards vouchers. Given that shifts towards cash are more pronounced and/or in larger-scale CVA responses, this aggregated to a slight shift towards cash globally for this subset of 16 response plans.

Box 1

Traceability of humanitarian CVA

The total volume of humanitarian CVA is frequently presented as a percentage share of total international humanitarian assistance (IHA). This is partly due to earlier research that provided a rough estimate of what might be the maximum share of IHA that could be implemented as CVA: between 37 and 42%, based on a number of high-level assumptions on the feasibility of CVA in different contexts and clusters. [10] DI estimates that in 2021 around 19% of IHA was implemented as CVA, around the same level as in the two previous years and representing an increase of almost 5 percentage points since 2017. This should be interpreted as a low estimate however, given that the global volume of CVA calculated by DI largely relies on bilateral data collection and does not necessarily capture all agencies implementing CVA, e.g., if they did not respond to the survey request (see Appendix 1 for more detail on methodology).

However, this percentage should also be treated with caution due to data on IHA and CVA each representing different parts of the humanitarian system. Data on IHA is mostly compiled from funding reported by donors, i.e. the first step in the humanitarian funding chain. Data on CVA is tracked at the point of delivery of assistance and reported directly by implementers. In the current data landscape on CVA, there is little to no data available on the steps in between a donor providing funding and it being delivered as cash, vouchers or any other modality of assistance. Many donors that have committed to increasing their support for CVA therefore struggle to evidence their progress in this regard, as they have to rely on their implementing partners to report CVA data back to them, though some donors, such as the US and the EC Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO), are able to quantify retrospectively the amount of cash (in the case of ECHO) or CVA implemented with their funding. [11] This is complicated further for softly or unmarked funding, or for large CVA projects with multiple donors, all making the attribution of CVA transfers to individual donors’ contributions more difficult. Standardised reporting on the total transfer volumes of CVA to interagency reporting platforms could close this data gap between donor funding and delivery modality of assistance (see section ‘The state of tracking humanitarian cash and voucher assistance’ below).

How does the planned use of CVA vary across contexts in 2022?

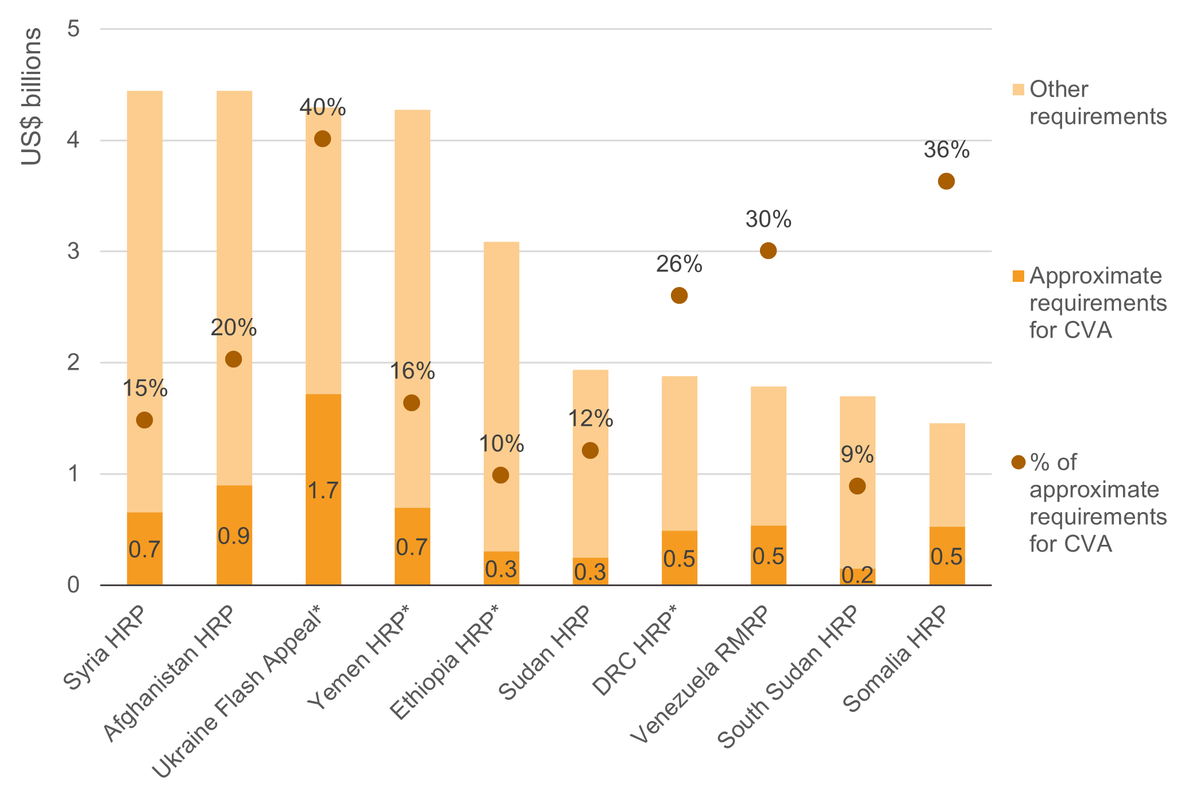

Early 2022 data on CVA within response planning reveals the varying scale of CVA across contexts, with the Ukraine response likely to drive an increase in global volumes of CVA. The percentage of response requirements for CVA varies across some of the largest humanitarian responses in 2022 from 9% in South Sudan to 40% in Ukraine ( Figure 2 ). This figure for Ukraine is based on the requirements for multi-purpose cash (MPC), which following the August revision to the Ukraine Flash Appeal made up US$1.7 billion. [12] This large-scale CVA response has driven increases in requirements for CVA shown in Figure 2 to 27% of total response requirements across the 10 response plans. Comparable data on requirements for CVA components across 2021 and 2022 is only available for 18 response plans with project-level data (see more on data availability below in the section ‘The state of tracking humanitarian cash and voucher assistance’). Those 18 plans represent close to a third of all financial requirements tracked by FTS in 2022 (US$15.8 billion). Of those plans, half increased and half decreased the scale of CVA within response requirements, meaning that in aggregate requirements for CVA remained stable at US$2.9 billion in 2022 and decreased slightly as a proportion of total requirements from 21 to 18% in light of higher overall response requirements.

Reliable data at the country or crisis level continues to be sparsely available. Granular data on the scale of CVA as part of response planning is only available for 6 of the largest 15 response plans tracked by FTS. For the remaining response plans that are unit-based or regional refugee response plans, high-level data on CVA was only available for MPC and/or food security. The lack of granular and comparable data makes it challenging to track the prevalence of CVA across different crisis contexts over time.

Figure 2: The scale of CVA in response planning varies widely across crises

Response requirements for CVA for the 10 largest response plans with available data, 2022

|

Plan

name |

Other requirements | Approximate requirements for CVA |

% of approximate requirements

for CVA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syria HRP | 3.8 | 0.7 | 15% |

| Afghanistan HRP | 3.5 | 0.9 | 20% |

| Ukraine Flash Appeal* | 2.6 | 1.7 | 40% |

| Yemen HRP* | 3.6 | 0.7 | 16% |

| Ethiopia HRP* | 2.8 | 0.3 | 10% |

| Sudan HRP | 1.7 | 0.3 | 12% |

| DRC HRP* | 1.4 | 0.5 | 26% |

| Venezuela RMRP | 1.3 | 0.5 | 30% |

| South Sudan HRP | 1.5 | 0.2 | 9% |

| Somalia HRP | 0.9 | 0.5 | 36% |

Source: DI based on Projects Module and UN OCHA FTS data and on information from response plan documents.

Notes: DRC = Democratic Republic of the Congo; HRP = humanitarian response plan; RMRP = refugee and migrant response plan. For response plans with an asterisk, data on requirements for CVA activities is only available for certain clusters and not the entire plan. Data on planned volumes of CVA for Afghanistan, Ukraine (multi-purpose cash/MPC only), Yemen (food security and MPC only), Ethiopia (food security only), DRC (MPC and food security only) and the Venezuela RMRP are taken from the respective response plan documents in absence of complete project data.

How much funding is required for CVA activities across different clusters in 2022?

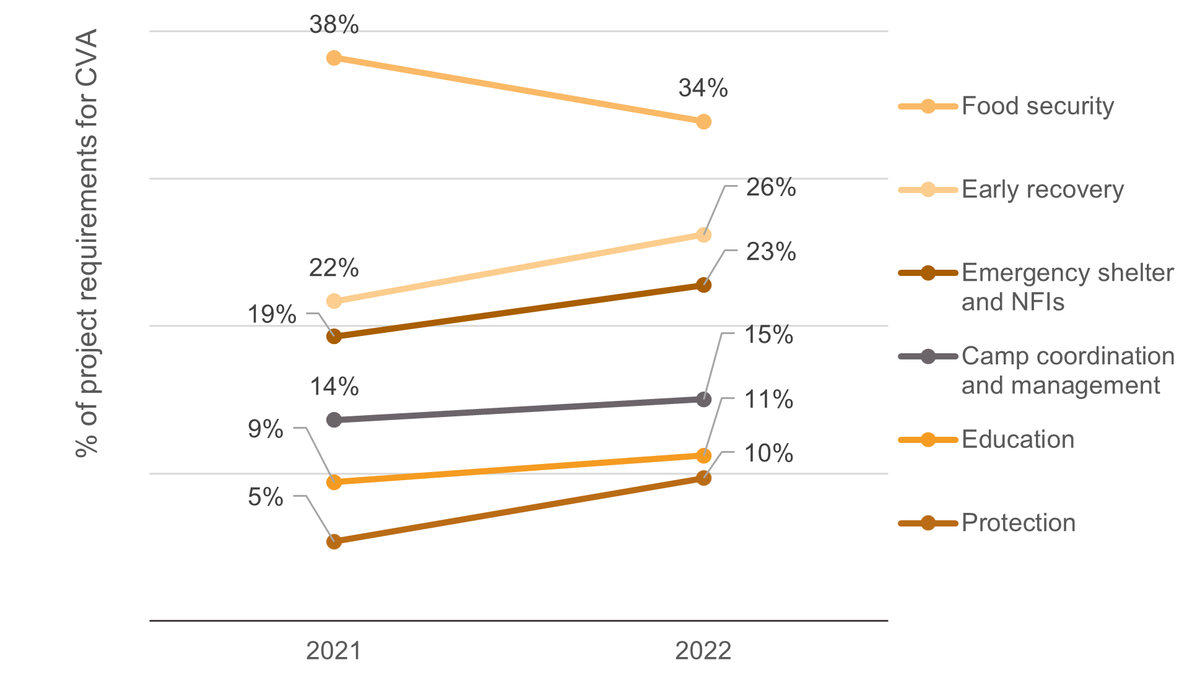

Data by cluster reveals an increase in the share of CVA across the early recovery, shelter and non-food items, education, protection and camp coordination and management clusters from 2021 to 2022 ( Figure 3 ). This is based on aggregate data from 18 response plans with total requirements of US$15.7 billion in 2022 that have project-level data on funding requested for CVA components in both 2021 and 2022. These five clusters and the food security cluster are the focus of this analysis given the significance of CVA activities in those six clusters, making up at least 10% of total funding requirements by cluster in 2022 aggregated across the study sample. The food security cluster, with perhaps unsurprisingly the largest share of CVA in the response planning of over a third of total required funding, witnessed a slight decline largely due to changes in the Sudan context. There the scale of planned CVA activities and associated financial requirements decreased significantly, from 82% of the food security cluster in 2021 to 27% in 2022. One of the reasons behind this decline is that some donors paused certain modalities, including cash transfers, following a military coup in October 2021 and that the financial framework in Sudan does not yet fully meet accountability and transparency requirements for all donors. Without the impact of Sudan, the aggregate relevance of planned CVA activities within the food security cluster across the 17 remaining response plans also increased slightly from 2021 to 2022. A closer investigation of which contexts are driving changes in the aggregate figures for the clusters in Figure 3 also provides an opportunity for learning. For instance, the protection cluster in Palestine increased its share of funding requirements for CVA activities from 7% to 21% by using cash to support essential protection services and emergency support for conflict-affected communities. [13] Protection cluster partners in this context also plan to introduce MPC in 2022, which will provide valuable lessons for other contexts on monitoring protection as well as intersectoral outcomes of MPC activities.

These country-specific examples highlight that while Figure 3 might be evidence for efforts within each cluster to raise awareness for where CVA can add value if appropriate and feasible in meeting sectoral objectives, this data is only the starting point for further discussions on what contextual factors facilitated increases or decreases in the significance of CVA. This highlights the importance of interpreting CVA data on clusters in light of contextual information. However, this is only possible if there is granular data on CVA available at the response level in the first place, which is not consistently the case.

Figure 3: The aggregate share of most cluster funding requirements for CVA activities increased slightly in 2022

Percentage share of requirements for CVA project components by selected clusters, 2021–2022

| Cluster | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

|

Camp coordination and

management |

14% | 15% |

| Early recovery | 22% | 26% |

| Education | 9% | 11% |

| Emergency shelter and NFIs | 19% | 23% |

| Food security | 38% | 34% |

| Protection | 5% | 10% |

Source: DI based on UN OCHA Projects Module data.

Notes: NFIs = non-food items. Projects included in the graph cover 18 response plans with data on the share of the CVA components out of total project funding requirements in both 2021 and 2022. Only clusters with a share of aggregate project requirements for CVA of 10% or more out of total funding requirements across all 18 response plans are included in the graph.

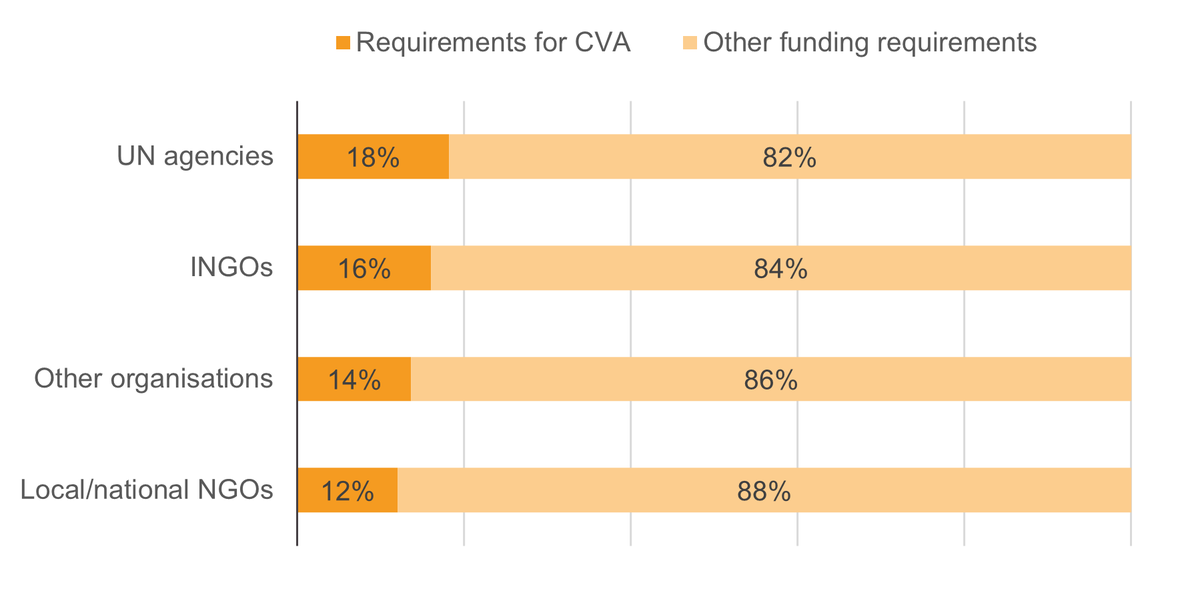

How do funding requirements for CVA activities vary across international and local/national agencies?

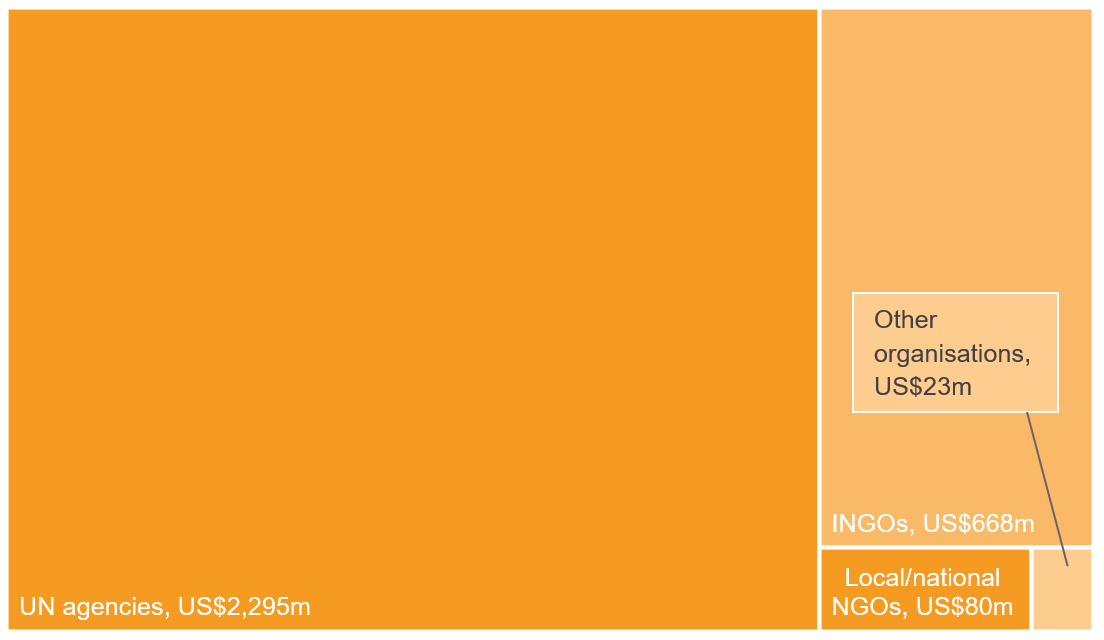

Across the different implementing agency types in 2022, international actors make up 97% of funding requirements for CVA activities for response plans with available data. This covers a sample of 19 response plans with total funding requirements of US$17.7 billion in 2022 that have disaggregated data on the size of CVA project components, UN agencies plan CVA to account for 18% of their activities ( Figure 4 ). This is slightly higher than the relative size of CVA project components for international NGOs (INGOs) and L/NNGOs at 16% and 12% respectively. These percentages need to be contextualised within the overall response requirements across these organisation types ( Figure 5 ). Given the large overall response requirements by UN agencies, they make three quarters (US$2.3 billion) of the total funding requests for CVA project components in 2022 for the sample. This compares to 22% for INGOs (US$668 million) and only 3% for L/NNGOs (US$80 million). The significance of the RCRC Movement for humanitarian CVA activities is not captured in the analysis sample, given that RCRC organisations often operate outside of the UN-managed response plans it is based on.

Figure 4: Differences in the share of funding requirements for CVA activities out of total funding requests are small across different organisation types

Percentage share of requirements for CVA project components by organisation type, 2022

|

Organisation

type |

Requirements for CVA | Other funding requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Local/national NGOs | 12% | 88% |

| Other organisations | 14% | 86% |

| INGOs | 16% | 84% |

| UN agencies | 18% | 82% |

Source: DI based on UN OCHA Projects Module data.

Notes: ‘Other organisations’ includes the RCRC Movement, consortia formed by UN agencies and NGOs and other organisation types. Projects included in the graph cover 19 response plans in 2022 with data on the share of the CVA components out of total project funding requirements. See the methodology in Appendix 1 for how local/national NGOs were identified.

Projects with a CVA component are more likely to be funded than those without one but this trend is much more pronounced for international actors than for local and national actors. Linking funding and project data reveals that in 2021 projects from international actors that had a CVA component were more than twice as likely to be funded than their other projects. This is based on data on 5,834 projects from 22 response plans in 2021 with a combined US$16.0 billion in requirements (methodological details are in Appendix 1 ). For UN agencies and INGOs, the likelihood for their CVA projects to have funding reported against them compared to their other projects was 151% and 100% higher, respectively. For L/NNGOs, however, the same effect was small at only a 7% greater chance of receiving funding for CVA projects compared to other projects. Against the backdrop of overall lower levels of funding for L/NNGOs compared to other organisation types under response plans, this raises the question of to what extent there exists a tension between donors’ commitments to increase the use of CVA and to localise their funding ( Box 2 ).

Figure 5: International agencies make up most of the funding requirements for CVA activities

Total funding requirements by organisation type for CVA components within response plans with available data, 2022

|

Organisation

type |

Requirements for CVA | |

|---|---|---|

| Local/national NGOs | 80 | |

| Other organisations | 23 | |

| INGOs | 668 | |

| UN agencies | 2,295 |

Source: DI based on UN OCHA Projects Module data.

Notes: ‘Other organisations’ includes the RCRC Movement, consortia formed by UN agencies and NGOs and other organisation types. Projects included in the graph cover 19 response plans in 2022 with data on the share of the CVA components out of total project funding requirements. See the methodology in Appendix 1 for how local and national NGOs were identified.

Box 2

Visibility of local and national NGOs implementing CVA

A number of country studies and the data available globally indicate that most humanitarian funding reaches L/NNGOs indirectly. [14] In the context of humanitarian CVA, this occurs for instance when international actors sub-grant funding to L/NNGOs for the implementation of aspects of CVA activities. The lack of publicly available data on indirect humanitarian funding to local and national actors more generally therefore also limits the visibility of their contributions to the delivery of CVA.

There is an added challenge for tracking downstream funding that is specific to CVA. A few respondents to DI and the CALP Network’s CVA survey have pointed to implementation models where funding is sub-granted for most aspects of the implementation of CVA projects, including beneficiary registration and post-distribution monitoring, but the funding for the actual transfer is held by the intermediary and transferred through their payment systems. In those cases, there is a lack of clarity on who to attribute the implementation of CVA to. This is not only a tracking issue, but also one about fairly recognising the contributions of all agencies involved in implementing a CVA program. The lack of transparency around sub-grants for the implementation of CVA program components also means there is a lack of data on to what extent overhead cost are covered under this arrangement. However, given that there is hardly any data publicly available on humanitarian sub-grants, increasing the transparency of all humanitarian downstream funding seems the more pressing issue to resolve.

Aside from issues of tracking and visibility of CVA implemented by L/NNGOs, forthcoming research commissioned by the CALP Network [15] also points to a tension perceived by humanitarian actors between the scale up of humanitarian CVA and the commitment to localise humanitarian funding. As the volume of humanitarian CVA continues to grow, donor preferences have led its implementation to become increasingly concentrated with international actors (UN agencies or INGO consortia). In the absence of comprehensive, public data on the contributions by L/NNGOs to humanitarian CVA, the humanitarian system will be unable to hold itself to account as it will not be possible to monitor whether increasing CVA might by accompanied by reduced funding to L/NNGOs.

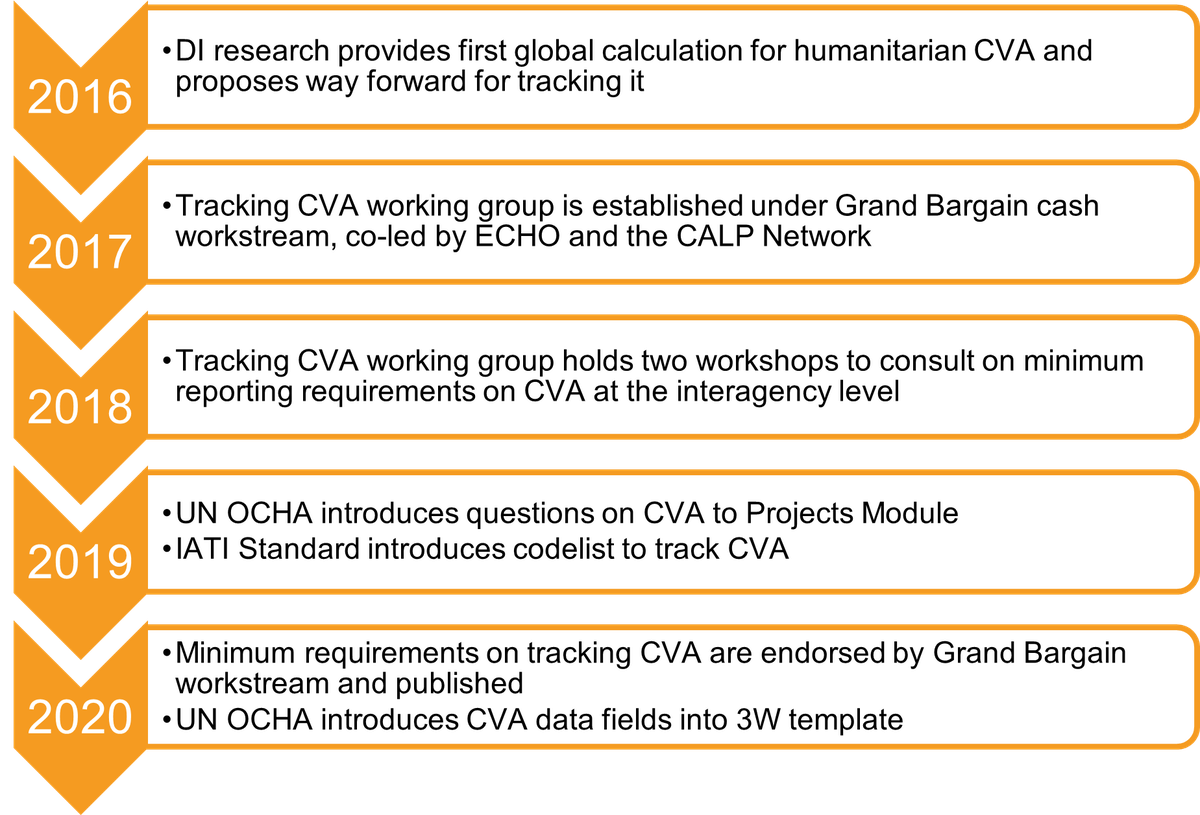

The state of tracking humanitarian cash and voucher assistance

The Grand Bargain commitment to ‘increase the use and coordination of cash-based programming’ was accompanied from the start by efforts to improve the available data on humanitarian CVA ( Figure 6 ). A working group was established under the Grand Bargain cash workstream to focus on identifying minimum requirements for tracking humanitarian CVA at the global interagency level. The working group held workshops to consult widely with more than 30 organisations on what CVA data should be the minimum for agencies to track and report, bearing in mind the potential use of that data and the cost in producing it. This consultation process included a scoping study on the technical and policy constraints towards better measurement and reporting of humanitarian CVA. [16] These consultations brought out clearly the potential use of improved data on humanitarian CVA for:

- Improved coordination of humanitarian CVA activities through better data on who does what and where, giving visibility to actors delivering CVA

- Greater accountability for donors and implementing agencies that have committed to increase the use of CVA where appropriate and feasible.

The working group reached the following agreement on the minimum requirements, which were subsequently endorsed by the Grand Bargain cash workstream: [17]

- CVA should be disaggregated into cash and vouchers in the tracking of humanitarian assistance

- The value of transfers to recipients should be the primary indicator for tracking cash and vouchers

- Reporting on all humanitarian CVA activities should include the objective, either sectoral or cross-sectoral .

It is against these minimum requirements that the publicly available data on CVA is evaluated below. In line with the objectives of the agreed reporting requirements, the focus lies on global interagency reporting platforms: UN OCHA’s humanitarian programme cycle tools and the IATI Standard. This is complemented by an exploration of available data on CVA at the response level.

Figure 6: Timeline of interagency progress on tracking humanitarian CVA

2016 - DI research provides first global calculation for humanitarian CVA and proposes way forward for tracking it 2017 - Tracking CVA working group is established under Grand Bargain cash workstream, co-led by ECHO and the CALP Network 2018 - Tracking CVA working group holds two workshops to consult on minimum reporting requirements on CVA at the interagency level 2019 - UN OCHA introduces questions on CVA to Projects Module; IATI Standard introduces codelist to track CVA 2020 - Minimum requirements on tracking CVA are endorsed by Grand Bargain workstream and published; UN OCHA introduces CVA data fields into 3W template

How can CVA be tracked in data tools supporting UN OCHA’s humanitarian programme cycle?

Since 2019, UN OCHA has included in its Projects Module [18] a standard set of questions on CVA . This has been operational in countries with projectised response plans plus a few exceptional cases of unit-based response plans that also opted for a project registration process for improved reporting and accountability. The reporting on CVA within the Projects Module includes:

- A ‘yes/no’ tick box that indicates whether a project involves cash and/or voucher assistance or not

- An additional request – if a project includes a CVA component – for the percentage of the overall project requirements for cash and separately for the same percentage for vouchers . These percentages are intended to include transfer values plus associated operational and delivery costs for CVA, meaning they should add up to 100% for projects with CVA as the only delivery modality.

This data provides an overview of CVA requirements for plans with a project registration process and is publicly accessible through an application programming interface (API) endpoint, alongside other project characteristics (such as implementing agency, cluster, total requested funding).

It is then possible to use UN OCHA’s Financial Tracking Service (FTS) data to match funding flows to projects with CVA components, if the corresponding project ID under the respective response plan is reported with the funding data . This currently needs to be done by the data user to obtain a granular dataset matching project and funding data, even though some FTS appeals pages display a top-level breakdown of requirements and funding by CVA and other projects. [19]

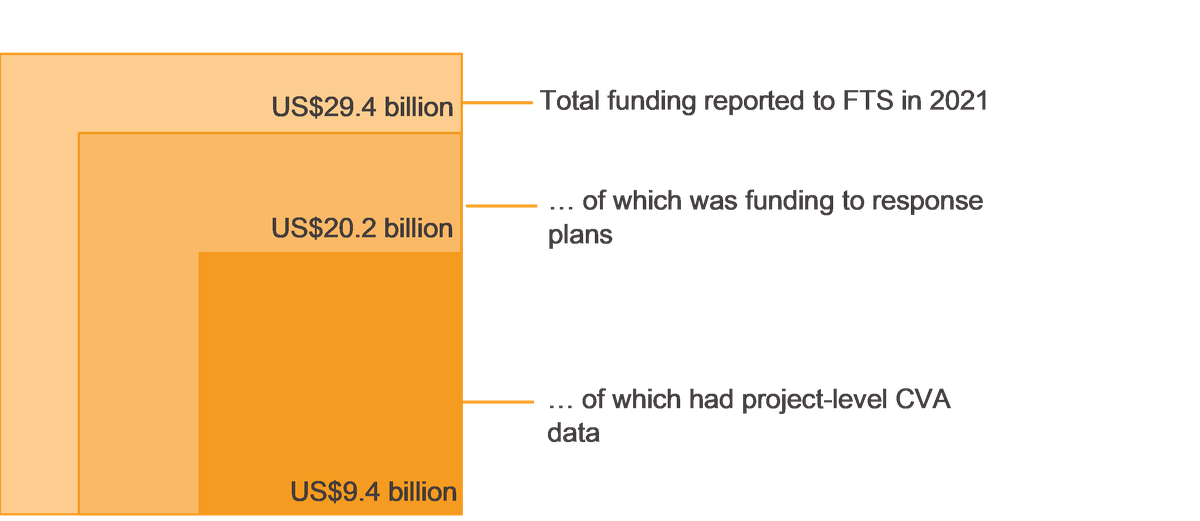

Matching funding flows and project information in that way yields what is currently the largest amount of granular and timely data on humanitarian CVA reported to interagency platforms. In terms of timeliness, projects data is available on the Projects Module as soon as the planning and project approval process is concluded for any given projectised response plan, and the corresponding funding data is reported in close to real-time to FTS. Project and funding data also usually captures information on the sector for the CVA project and who implements it. Given that matching funding and project information is only possible for data on projectised response plans with questions on CVA in their project registration process, this provides information on a subset of around a third of humanitarian funding (US$9.4 billion) captured by FTS for 2021 ( Figure 7 ). This subset for 2021 includes 4,517 projects under 24 response plans with combined requirements of US$16.8 billion, of which 1,255 are reported to have a CVA component. Total reported requirements for only those CVA components amounts to US$3.3 billion. To estimate funding figures for those CVA components, we need to make the simplifying assumption that for a project with, e.g. 40% of project requirements reported for CVA, the same percentage of funding to that project will be implemented as CVA. There are two major issues with this. Firstly, on average only 62% of all funding to projectised response plans with CVA data has information on which project it is supporting – for the remainder, it is not possible to match funding with project data. Secondly, the percentages representing the share of the project implemented as cash and/or voucher assistance can change after the project registration process, sometimes significantly, if the context changes.

Figure 7: Project level data on CVA is available for only a third of funding tracked by FTS

Funding to response plans with project-level data on CVA relative to other funding tracked by FTS, 2021

US$29.4 billion reported to FTS in 2021, of which US$20.2 billion was funding to response plans, of which US$9.4 billion had project-level CVA data.

Source: Development Initiatives based on UN OCHA FTS data.

Notes: Total funding reported to FTS includes that provided by public and private donors, but not that provided by agencies that also implement humanitarian assistance, to avoid double-counting.

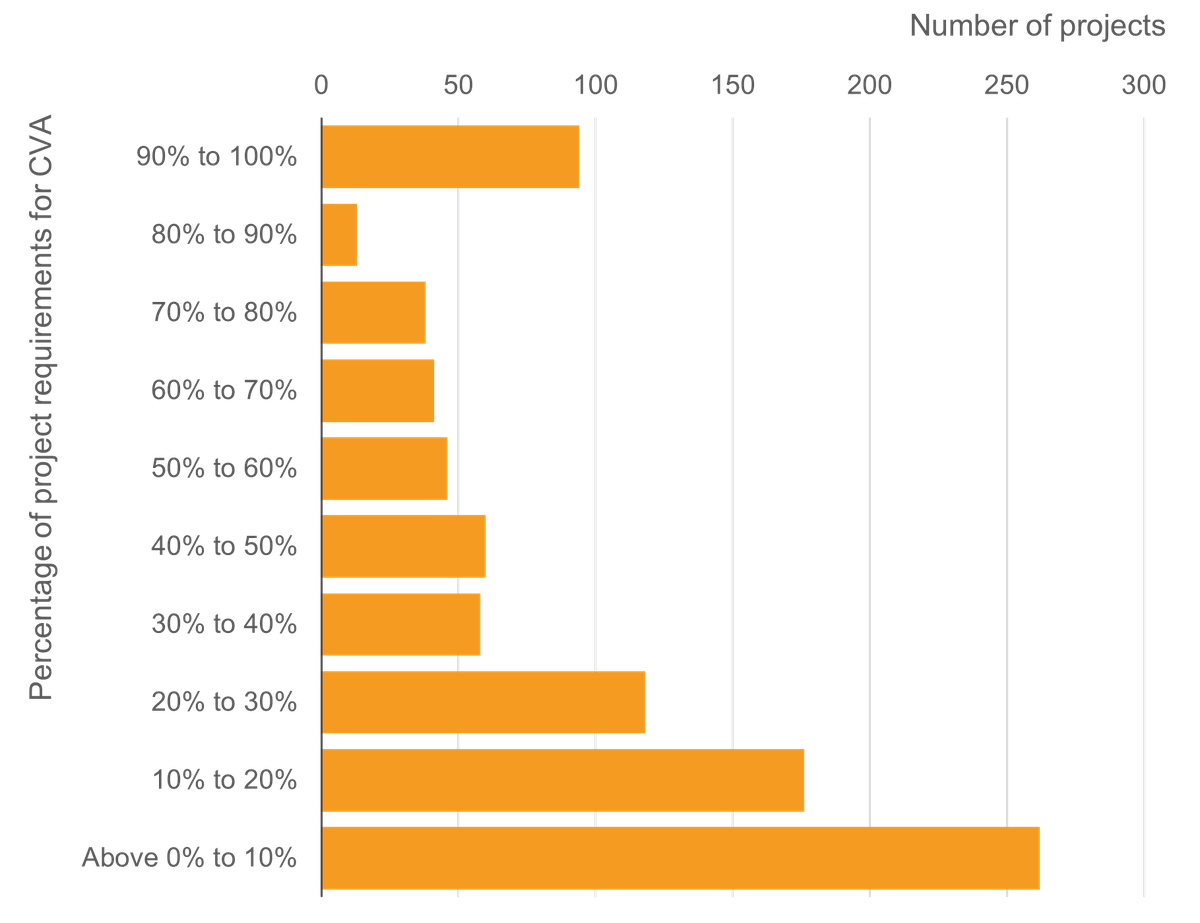

While it is possible to tag funding flows outside of projectised plans whether or not they support CVA activities, this is only rarely reported and even then does not quantify how much of that funding is implemented as CVA. Outside of projectised plans, FTS also allows reporters of funding flows to be tagged as CVA without the need to link it with project information. This tag acts as a flag that highlights whether or not the activity receiving the funding has a CVA component, without specifying how large or small. The wide spread of the relative size of CVA components within projects based on 2022 data for over 900 project requirements ( Figure 8 ) means it is hard to infer from this CVA flag for funding flows how much of this funding actually ends up as CVA transfers to recipients. The flag also does not disaggregate by cash or vouchers. Finally, donors often do not have information on what delivery modalities they support with their funding when reporting to FTS. This is reflected in the relatively small number of funding flows reported with this flag, hovering at between only 1–2% of funding captured by FTS between 2018 and 2022.

Figure 8: Most projects have CVA components of 30% of the project budget or less

Distribution of response plan projects by percentage of project funding requirements for CVA, 2022

|

Percentage

of project requirements for CVA |

Number of projects | |

|---|---|---|

| Above 0% to 10% | 262 | |

| 10% to 20% | 176 | |

| 20% to 30% | 118 | |

| 30% to 40% | 58 | |

| 40% to 50% | 60 | |

| 50% to 60% | 46 | |

| 60% to 70% | 41 | |

| 70% to 80% | 38 | |

| 80% to 90% | 13 | |

| 90% to 100% | 94 |

Source: DI based on UN OCHA’s Projects Module data.

Notes: Data reflected in the graph covers 906 projects from 16 response plans in 2022 with an estimated percentage share of total project requirements for CVA – including associated operational and delivery costs for that assistance – greater than zero. 17 projects with that percentage exceeding 100% were excluded due to misreporting.

A humanitarian response plan document can include a designated chapter that outlines details on the role of CVA and/or of multi-purpose cash (MPC) activities in the response. In cases where chapters are accompanied by financial requirements for the MPC activities they cover, FTS offers the possibility to report funding flows to projects included under those requirements. Each year, an average of five response plans have had separate requirements for MPC over the last five years. For 2022 at the time of writing, the large financial requirement for the MPC response in Ukraine (US$1.7 billion) meant MPC requirements made up 4.1% of total financial requirements for response plans tracked by FTS that year, compared to less than 1% in previous years. However, funding flow data on FTS from donors to implementers of MPC does not provide insight into the total volume of MPC transfers to recipients – though this might be tracked separately at the country level (see section ‘ Country-level CVA data ’ below). Due to the cross-sectoral nature of MPC interventions, funding flows targeting MPC field clusters are frequently reported to also contribute to other field clusters, making it difficult to attribute funding against the specific MPC requirements, especially for response plans where funding cannot be linked to projects. In most crisis contexts and without separate financial requirements for MPC, there is no standardised way of tracking funding to or the amount of transfers facilitated by MPC activities on either FTS or the Projects Module.

Crucially, neither FTS nor the Projects Module have the mandate or design to facilitate reporting on project expenditure on cash, vouchers or other delivery modalities. FTS, as collectively determined by the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC), provides an overview of funding flows to humanitarian operations to inform resource mobilisation efforts. The Projects Module facilitates strategic response planning and therefore does not attempt to also monitor project expenditure. What is therefore required to meet the minimum reporting requirements on CVA, i.e. to capture data on transfer values disaggregated by cash and vouchers, is to systematically integrate data collection on this with monitoring information systems and to better link those with planning and resource mobilisation data.

Recommendations

- Humanitarian agencies participating in project-based response plans should ensure that information on CVA components for the respective project, disaggregated by cash and vouchers, is submitted to the Projects Module, that significant changes to the size of the CVA component are updated retrospectively, and that all received funding under the response plan is recorded against the relevant project.

- UN OCHA’s FTS should create a CVA data summary page on the FTS website that displays the available data on funding required for CVA project components under response plans from the Projects Module and links this with funding reported to those projects. Making CVA data available in that way by response plan/country, implementing agency, donor and cluster will hopefully improve the available data by creating a positive feedback loop of data visibility, use and revision.

How can data on humanitarian CVA be published to the IATI Standard?

In July 2019, the IATI Standard introduced the option to publish data on CVA for projects and funding flows. [20] In line with the agreement by the Tracking CVA working group, it enables reporting on CVA transfer values disaggregated by cash and voucher assistance if used appropriately. The IATI humanitarian reporting guidance outlines how to use the IATI Standard to publish CVA data, alongside other humanitarian data categories. [21]

Humanitarian assistance can be published to IATI as either cash or voucher assistance at the project level – in IATI terminology and data structure described as an ‘activity’ – and at the transaction level. This can be done by assigning the modality – in IATI terminology described as ‘aid type’ – of either cash or voucher assistance. [22] This is entirely optional; if not relevant, i.e., for projects that do not include CVA, data on this aid type can be omitted. The degree of data use from the two ways of publishing CVA data to the IATI Standard work differs as follows:

- Activity-level IATI reporting on CVA allows data publishers to assign the aid type of either cash or vouchers to any project. [23] This would add a flag to the projects that would allow data users to identify whether a project contains cash transfers, vouchers or neither. However, tagging projects in this way as either cash or voucher programming does not reveal what share of the project budget amounts to CVA and thereby does not quantify CVA transfers to recipients.

- Transaction-level IATI reporting on CVA allows data publishers to assign the aid type of either cash or vouchers to any project-related expenditure. [24] The IATI publisher can decide how to break down the project expenditure data and how regularly to publish it, likely aggregated over a certain time period and not as individual transactions. Given that this information relates to project expenditure, it needs to be published by the organisation delivering CVA. Publishing CVA data to IATI in this way would allow data users to quantify transfer values to recipients, disaggregated by cash and vouchers, which fulfils the minimum reporting requirements agreed on by the Grand Bargain cash workstream.

Reporting on the sectoral objective for humanitarian assistance is also possible in the IATI Standard by selecting any of the global clusters. [25] However, the sectoral reference list for the IATI Standard does not include a cross-sectoral category, meaning it is currently not possible to report on MPC using the sector reporting.

Many agencies that implement large amounts of CVA are already publishing data to the 2.03 version of the IATI Standard, which allows them to also report on CVA. This includes WFP, UNHCR, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), International Committee of the Red Cross, Norwegian Refugee Council, several affiliate organisations of World Vision, Save the Children, CARE and more. Organisations with large CVA portfolios that do not yet publish data to that version of the IATI Standard include UNICEF, the Food and Agriculture Organization, a number of affiliates from large INGOs and several RCRC National Societies – though for the latter, granular data is publicly available on the RCRC’s cash maps. [26] Some of those organisations, e.g. WFP, UNHCR and the IFRC, [27] also already publish data on their expenditure to IATI, though not yet on CVA transfers within that.

Even though the option to publish CVA data to the IATI Standard was introduced over two years ago, it has hardly been used. At the time of writing, there are only four organisations with any IATI data on CVA at the activity level for 59 projects: [28] Action Aid Bangladesh, Action Aid UK, Danish Refugee Council and Oxfam Novib. While there are 10 organisations with CVA data at the transaction level to date, [29] closer inspection of the data reveals that none of it actually refers to transfer volumes of either cash or voucher assistance to recipients, and therefore it is misreporting.

This poses the question of what level of effort it would require for organisations implementing large volumes of CVA and that already publish expenditure data to IATI to incorporate information on CVA transfers to recipients into their IATI reporting processes. For implementing organisations with centralised project reporting and CVA monitoring systems, e.g., WFP or UNHCR, this could present a low-hanging fruit of making granular and comparable CVA data publicly available in regular intervals. For networks of organisations that rely on their affiliates to individually publish data to IATI, such as the aforementioned INGO networks or the International RCRC Movement, this would likely be a more costly and time-consuming effort in first rolling out IATI reporting across the respective network and producing guidance on how to incorporate CVA data within that. However, there are also potential cost savings by streamlining the reporting of aid activities by, e.g., response plan, cluster, subnational administrative region and delivery modality – all of which are part of the IATI Standard. Published only once, this data can then be used often for reporting on funding progress against response plans, for coordination efforts such as 3Ws (see next section) and to report back to donors. [30]

Recommendations

- Organisations implementing CVA and publishing IATI data should report on CVA transfer values to recipients as expenditure under their IATI activities. This should occur alongside reporting on other (humanitarian) project attributes to harness synergies between IATI and other reporting processes (e.g., response plans, 3Ws, to donors) to ultimately reduce the overall reporting burden.

- The IATI technical team should update the humanitarian guidance to explicitly encourage reporting on CVA to IATI at the transaction level and for this aid type to only be applied to project expenditures. The guidance should make clear that this is currently the only possible way to meet the minimum reporting requirements agreed on by the Grand Bargain cash workstream.

- The IATI publishing community should in the medium term upgrade the IATI Standard [31] to enable this by:

– Creating a new, optional IATI element, with a new codelist and rules, to report on delivery modality, which includes cash, vouchers, in-kind assistance and services.

– Defining the rules of this delivery modality codelist such that it can only be applied to the transaction type ‘expenditure’.

Country-level CVA data

Different crisis contexts often have different reporting requirements for agencies participating in the humanitarian response, depending on the response priorities, and this also applies to reporting on CVA. The minimum requirements for tracking CVA that were endorsed by the Grand Bargain cash workstream outline what should be the smallest common denominator across responses to generate comparable data at the global level. However, timely and disaggregated data on cash and voucher transfer values alongside their sectoral objectives is available in only few contexts.

In 2020, UN OCHA, in consultation with the IASC Global Cluster Coordination Group, introduced a new template for the response monitoring of ‘Who does What Where’ (3Ws) based on the agreement by the tracking CVA working group on minimum requirements. This template includes standard fields to report on the delivery modality and transfer value for each humanitarian activity. [32] The selection options for delivery modality are in-kind assistance, service delivery, cash or vouchers. The template also includes additional optional fields on, e.g., conditionality, frequency of transfer or the CVA delivery mechanism (such as E-voucher, paper voucher, smart card, cash in hand).

Despite the inclusion of standard reporting fields on delivery modality, this information is not yet accessible through the Global 3W dashboard. [33] There are a number of challenges with consistently obtaining this data in a comparable format across response plans. Actors at the country level can ultimately decide on the standard data collection fields for the country-specific 3Ws. Clusters are then responsible for creating and disseminating their own more detailed 3Ws, and for collecting the data. Clusters subsequently submit common information from the standard fields to UN OCHA to create the inter-cluster emergency 3W products. Given the decentralised reporting process, not all country teams may choose delivery modalities as standard fields and clusters may opt not to include this in their more detailed 3Ws. This means that response-level data on CVA currently seems to be often collected and shared through cash working groups in separate reporting processes.

Table 1 provides an overview of CVA data availability at the response level for the 10 largest recipient locations of humanitarian funding at the time of writing, in all cases published by the respective cash working group. This reveals that in almost all examined cases, data collated by the cash working groups meets the minimum requirements on reporting CVA, in that it includes data on transfer values, disaggregation by cash and vouchers, and information on the sectoral objective of CVA. In terms of the sector reporting on CVA, there is a variation in approaches to the tracking of MPC, though it is captured separately in most cases as MPC or MPCA (with ‘A’ for assistance). Where not shown separately, it is unclear whether it’s represented by CVA falling under a ‘multisector’ category or is also included under other clusters’ reporting. There is also a variation in timeliness and accessibility of CVA data across the 10 contexts in Table 1. Only three contexts (Ukraine, Somalia and South Sudan) have publicly available data on CVA on the last quarter or more recent. This limits the usability of this data to coordinate CVA activities at the country level. In terms of accessibility, the granular data underlying the CVA response overviews is public for only two contexts – Somalia and Ukraine. For the remaining contexts, data is published as pre-determined breakdowns and often in aggregate, meaning there is limited possibility for in-country or global actors to understand in detail what the data includes and what might be missing.

Table 1: CVA data availability at the response level for the 10 largest recipient locations of humanitarian funding in 2022 as reported to FTS to date

| Country | Timeliness | Accessibility | Meets minimum requirements | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ukraine | Yes | Yes | Yes |

OCHA

Ukraine |

| Afghanistan | Somewhat | Somewhat | Yes |

Afghanistan

Cash and Voucher Working Group |

| Ethiopia | No | Somewhat | Yes |

Ethiopia

Cash Working Group |

| Yemen | Somewhat | Somewhat | Yes |

Cash

and Market Working Group |

| Syria | Somewhat | Somewhat | Yes |

Cash

Working Group (whole of Syria) Cash Working Group - Northwest Syria |

| Somalia | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Somalia

Cash Working Group |

| South Sudan | Yes | Somewhat | Somewhat |

Cash

Working Group South Sudan |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | Somewhat | Somewhat | Yes |

DRC

Cash Working Group |

| Sudan | Somewhat | Somewhat | Yes |

Sudan

Cash Working Group |

| Lebanon | No | Somewhat | Yes |

Basic

Assistance Working Group - Lebanon |

Source: Development Initiatives based on publicly available information from cash working groups. Source links to the available data on CVA are provided in the PDF version of this report.

Notes: The thresholds for the assessment of timeliness are whether data is available on CVA within the last quarter, and if not, whether there is data on CVA within the last 12 months. The thresholds for the assessment of accessibility are whether the underlying, granular data is downloadable, and if not, whether summary visualisations – either in PDF format or through Microsoft Power BI – are publicly accessible.

In summary, data on CVA is collected at the response level in all large-scale humanitarian crisis contexts and mostly meets the minimum reporting requirements as agreed by the Grand Bargain cash workstream. But accessibility and timeliness of that data varies. There currently is also a disconnect between response-level and global, interagency reporting on CVA, with data from the former not reflected anywhere in the latter. Situating the responsibility for tracking CVA at the response level within the new cash coordination model provides an opportunity to generate comparable and better quality data on CVA. The lowest common denominator of this data in terms of transfer values as cash or voucher assistance and sectoral objectives could then be reflected on interagency reporting systems.

Recommendations

- The global Cash Advisory Group should agree on who is responsible for tracking CVA within the new cash coordination model. Data should be tracked in line with the agreed minimum reporting requirements. The tracking responsibility should be clearly assigned so that clusters and cash working groups can receive specific guidance on what information on CVA to track at the response level during planning and monitoring. The goal should be to produce timely, granular and publicly accessible data. The common reporting indicators by aligning with the minimum CVA reporting requirements should feed from the response level into global, interagency reporting systems.

- Donors should sufficiently resource CVA information management alongside other coordination functions at the field level. This is necessary to collate and share CVA data with the required qualities to enhance coordination of the response.

Conclusion

The most recently available data on global volumes of humanitarian CVA points to a continued increase in 2022, driven by the large-scale multi-purpose cash response in Ukraine. Early 2022 data on response planning that captures around a third of the humanitarian system confirms this trend within multiple clusters, even though contextual factors ultimately seem to determine the scale of CVA activities across crisis countries. It also reveals the concentration of humanitarian CVA with international responders. Shedding more light on the contributions of local and national actors to humanitarian CVA, especially by increasing transparency on sub-grants, must be a priority to monitor the potential tension between the commitments to increase CVA and to localise funding.

More also needs to be done on how to better link humanitarian CVA with data on cash assistance through government-led social protection systems in crisis contexts. The large-scale expansion of social protection programmes in response to the Covid-19 pandemic has intensified efforts to collate data on the scale of cash transfers within those programmes. [34] However, the current data landscape also makes it difficult to assess to what extent crisis-affected populations are assisted through social protection systems, how the scale of this assistance compares to CVA delivered by the humanitarian system, and whether the scale up of social protection systems in response to crises is financed domestically or internationally. Those data gaps need to be filled to avoid missed opportunities in terms of linking humanitarian CVA and social protection and to better inform coordination and funding efforts.

Reaching an agreement among the Grand Bargain signatories on the minimum requirements for tracking CVA was rightly considered a success. The focus has since been on improving the quality of CVA programming and on agreeing a new cash coordination model, both important areas of progress. However, the minimum requirements were only the starting point for enhancing comparable, comprehensive and timely data on where CVA is implemented and by whom. As the above research shows, little progress has been made since in implementing this agreement by reporting more and better CVA data to interagency reporting platforms. Improvements by organisations to track CVA internally and at the response level now put the humanitarian system in a promising position to align fragmented CVA data with the minimum requirements. Improving the global CVA data landscape in that way will enable a better coordinated response, building on the recently endorsed cash coordination model and sustaining the increase in the scale of humanitarian CVA.

Finally, the efforts to improve the tracking of CVA are an important piece of the greater transparency puzzle for the humanitarian system. Data on where and how humanitarian assistance is delivered is needed to hold actors to account for meeting needs where they are greatest, especially in the context of an increasingly stretched and underfunded system. The tracking discussion therefore needs to be extended beyond CVA to other delivery modalities (in-kind and services). This is to avoid imposing additional reporting responsibilities on only CVA actors and, more importantly, to hold up a mirror to the entire humanitarian system for the last mile of aid delivery.

Appendix 1: Methodology

There are two main datasets on humanitarian cash and voucher assistance (CVA) analysed in this report. The first one underlies Figure 1 and is largely based on data collected bilaterally by DI and the CALP Network from organisations implementing humanitarian CVA. This dataset continues to provide the most comprehensive evidence base for the total global volume of humanitarian CVA. In an annual exercise DI and the CALP Network request data on the following indicators, in line with the minimum reporting requirements agreed by the Grand Bargain cash workstream:

- Overall cash and voucher programming costs, including transfer values plus associated programming costs

- Transfer values of humanitarian CVA, if possible disaggregated by cash and vouchers

- Value of CVA received in sub-grants from other implementing agencies and that provided as sub-grants to other implementing agencies. This is to avoid double-counting between different survey submissions by attributing wherever possible the amount of CVA to the agency delivering it.

Survey data is consistently provided by between 25 and 30 organisations each year, with not all organisations providing data across all years. Where this may lead to fluctuations in the data, this is highlighted. The survey data provides global, organisational overviews of CVA activities for survey respondents. It does not contain information by country or sector, as the survey was designed to minimise any additional reporting burden while still generating data useful to the humanitarian system. Data is collected from agencies with the understanding that it will not be attributed to the survey respondent, unless this data is publicly available elsewhere. This is to increase the response rate. For some organisations, the requested data is taken from public sources where available (e.g., the RCRC Cash Maps , WFP’s CVA dashboard and UNHCR’s annual cash report ). However, given that this data is publicly available and sufficiently up to date for only a few organisations, and given that information on sub-grants for the implementation of CVA is often not included, most of the data continues to be collected manually.

Given that not all humanitarian agencies implementing humanitarian CVA might respond to the survey, an additional analysis of humanitarian funding flows reported to UN OCHA’s Financial Tracking Service (FTS) is carried out to identify funding targeting CVA activities by agencies that did not provide survey data. This funding is identified through a combination of sectoral data and modality data on CVA (see section ‘The state of tracking humanitarian cash and voucher assistance’ above for more detail) with a keyword search on the descriptions of funding flows. This allows for the identification of an additional US$150 million to US$250 million of humanitarian CVA depending on the analysis year.

Combining survey data with FTS data then yields the dataset underlying the global volumes of humanitarian CVA. There are parts of the humanitarian system that might be missing from this dataset, for instance data on organisations that did not respond to the survey and are not accurately reflected on interagency reporting platform. It also includes very few instances of cash transfers through social protection systems in crisis contexts in cases where the scale up was funded and reported by international donors to UN OCHA’s FTS.

Finally, data on the overall programming costs of CVA is only provided by around a third of survey respondents in 2021, down from half in 2015. Almost all agencies are able to report on transfer values, and most can disaggregate this by CVA. For agencies that did not provide data on their overall programming costs, this is estimated using the global average share across all agencies of transfer values out of total CVA programming costs. In 2021, this share was at 79%.

The second dataset analysed in this report in Figures 2–5 is to our knowledge the first analysis of CVA data captured by UN OCHA’s Projects Module. The section ‘The state of tracking humanitarian cash and voucher assistance’ outlines what data on CVA is requested as part of the project registration process for response plans and what share of the humanitarian interagency response is captured by this data.

Our analysis of the project data first relied on identifying all of the questions relevant to CVA in English, Spanish and French, and to categorise them by whether they act as a yes/no ‘flag’ on whether a project has a CVA component or whether they quantify the size of the CVA project components. At the time of writing and for 2022 data, there are 20 response plans on the Projects Module that contain project information on CVA, and 19 of those also capture the percentage share of CVA components for relevant projects. We analysed 4,057 projects across those 19 response plans on whether that had a CVA component and how large those components were relative to the overall project requirements. We then broke down this data by context, implementing agency type and cluster.

As part of our analysis by implementing agency type, we identified local and national NGOs by downloading from FTS the full dataset on organisations with their corresponding types (such as UN agency, NGO) and on where they are based. We then identified NGOs that were based in the same country as the response plan location and subsequently manually reclassified affiliates of international NGO networks as INGOs, in line with the definitions paper by the Localisation Marker working group. [35]

To identify the likelihood of CVA projects (which we identified as outlined above) receiving funding, we matched funding flows from FTS that were reported with project IDs to the respective project data from the Projects Module. Analysis of funding data reported against projectised response plans revealed that in 2021, only 62% of funding to those plans was reported with a project ID. Given that the absolute funding data by project was therefore not comprehensive, we instead carried out comparative analysis on whether projects with or without CVA components were reported to have received funding. This analysis also assumes that CVA was delivered as part of project delivery if initially reported during the planning process as a project component. In future research it might be possible to check this assumption by investigating the flow descriptions of funding to CVA projects, however, in many cases these do not contain sufficient detail on the delivery modality.

Downloads

Notes

-

1

ODI, 2021. The Grand Bargain at five years: An independent review. Available at: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/grand-bargain-official-website/grand-bargain-annual-independent-report-2021Return to source text

-

2

Details on the new cash coordination model, endorsed by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee in March 2022, are available at: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/inter-agency-standing-committee/iasc-cash-coordination-modelReturn to source text

-

3

ODI, 2022. The Grand Bargain in 2021: An independent review, page 78. Available at: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/2022-06/Grand%20Bargain%20Annual%20Independent%20Report%202022.pdfReturn to source text

-

4

UN OCHA, 2022. 2022 Flood Response Plan Pakistan. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/attachments/dda275d9-1d76-446b-b8f2-8f563672310d/Pakistan%202022%20Floods%20Response%20Plan%20-%20August%202022.pdfReturn to source text

-

5

Government of Pakistan, 2022. Benazir Income Support Programme ensuring speedy disbursement of Rs.25,000 to flood affected families. Available at: https://www.bisp.gov.pk/NewsDetail/YTMzYThhNjktZDMzZi00M2Q3LTk1YTctNjViZGIzNzZmMjc0Return to source text

Related content

Recipients and delivery of humanitarian funding

Efforts to improve the quality, efficiency and effectiveness of funding continued in 2021 but progress on the Grand Bargain is uneven as direct funding to local and national actors fell to its lowest level in five years.

Funding for gender-relevant humanitarian response

DI examines the impact of Covid-19 on international funding for gender-related humanitarian programming, finding that global efforts to support gender equality and support women and girls in humanitarian crises are falling short.

Tracking the global humanitarian response to Covid-19

An overview of the humanitarian response to Covid-19, showing general humanitarian funding trends as well as the quality of funding and reporting