Spiralling emergency accommodation costs from the UK’s Home Office are diverting aid from the world’s poorest

This blog argues that the UK should remove in-donor refugee costs from its aid target to avoid failing the people most in need.

Since 2019, the amount of official development assistance (ODA) that the UK spends on in-donor refugee costs has grown dramatically, driven entirely by increasing costs of ‘initial accommodation’: emergency shelter for asylum seekers arriving in the country. But asylum seekers are not living in luxury: many live in unacceptable conditions, despite this additional expenditure diverting resources that could otherwise have made a real difference to the world’s poorest people.

There are multiple reasons for the increase, including the Home Office’s decision to stop making asylum seekers homeless during the Covid-19 pandemic due to public health concerns. The situation has arguably been exacerbated by the Home Office’s lack of incentive to control costs because the ODA budget is not theirs to account for.

As the UK’s International Development Committee recently concluded , the UK is not required to count such costs towards the ODA budget, yet it does. Neither Luxembourg nor Australia count in-donor refugee costs in ODA, and other countries omit other categories that they disagree with, such as counting Covid vaccines. This blog argues that the UK should follow suit. Humane treatment of asylum seekers should not be set in opposition to poverty reduction.

► Read more from DI about ODA (aid)

► Share your thoughts with us on Twitter or LinkedIn

► Sign up to our newsletter

Initial accommodation costs have increased fourteen-fold since 2019

Between 2019 and 2021, the UK’s spending on in-donor refugee costs increased from £477 million to £1,052 million, or from 3% to 9% of the UK’s total ODA budget. This was not caused by an increase in refugee/asylum-seeker [1] numbers. While the number of asylum applications and resettled refugees combined was around 20% larger in 2021, the majority of applications in 2021 were made later in the year, so most of these associated costs will be in 2022. [2] Instead, the increase has been driven by a meteoric rise in initial accommodation costs.

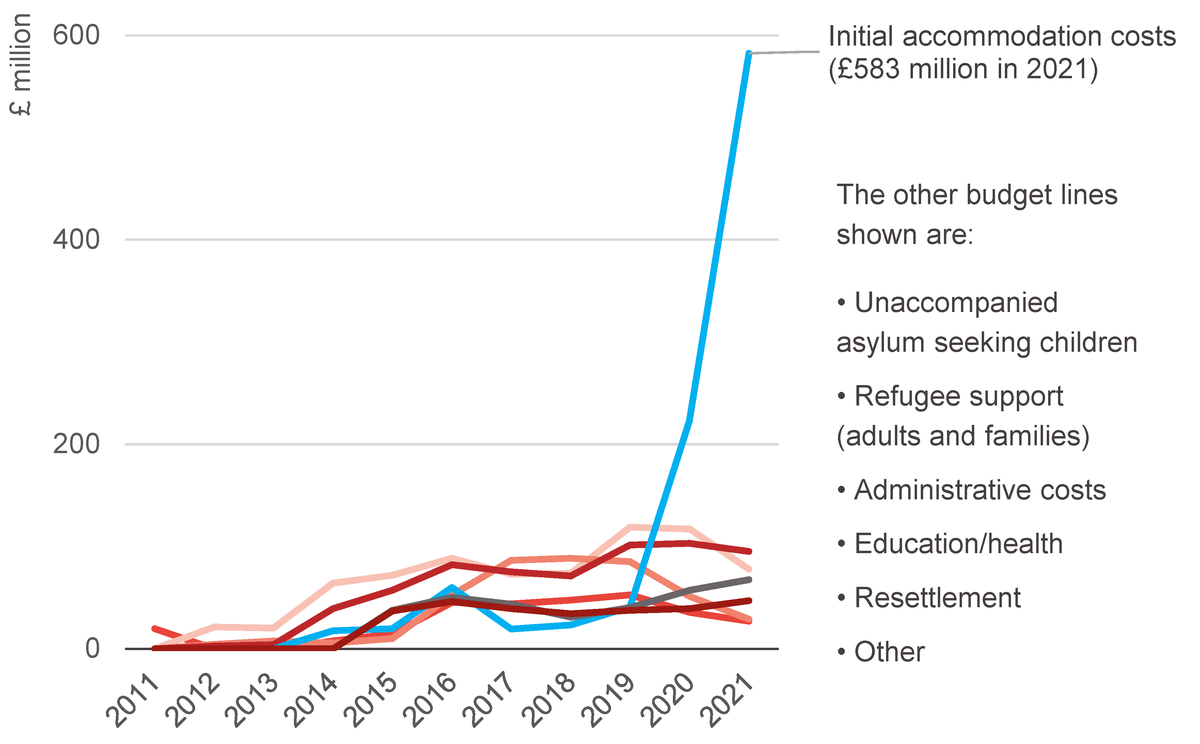

Figure 1: In-donor refugee costs in the UK by category, 2011–2021

Line chart showing that initial accommodation costs for refugees have increased many times faster than other costs, such as unaccompanied asylum-seeking children, education and health, or resettlement.

Notes: Education/Health includes all Department of Health and Social Care and Department of Education spend.

Source: DI Analysis of Statistics on International Development.

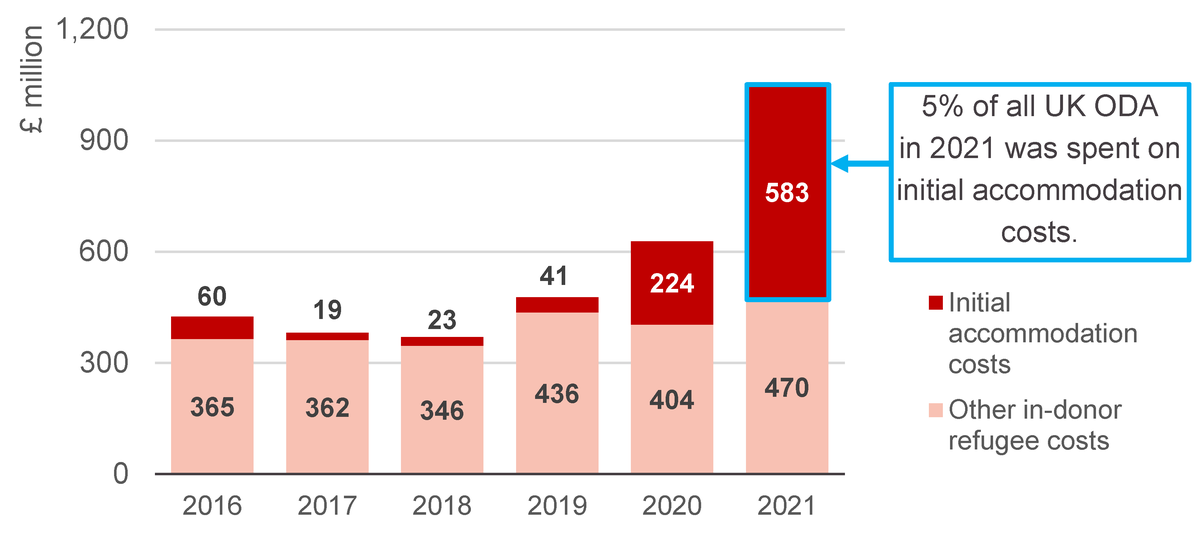

Initial accommodation costs for asylum seekers increased from £41 million in 2019 to £583 million [3] in 2021. This fourteen-fold increase means the category now accounts for 55% of in-donor refugee costs (and 5% of total ODA, considerably more than bilateral ODA spent on education ). This emergency accommodation category accounts for essentially all of the increase in in-donor refugee costs since 2019 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: In-donor refugee costs since 2016: initial accommodation versus other categories

Bar chart showing that £583 million was spent on initial accommodation of refugees in 2021 - up from £224 million in 2020, and £41 million in 2019.

Source: DI Analysis of Statistics on International Development.

It is hard to estimate the per-capita cost because data on asylum applications and support (from the Home Office) is not well harmonised with ODA data. However, if total expenditure on initial accommodation is simply divided by the number of asylum applications in 2021, then this implies an average per capita cost of around £13,000. This is more than the average cost of renting a three-bedroom house in England for a year.

But the UK government has not decided to roll out the red carpet for asylum seekers. Despite this dramatic increase in costs, accommodation conditions remain unacceptable. DI met with an asylum seeker, Sarah (see the case study ), whose experiences of the duration and quality of accommodation reflect what’s already widely reported: stays can be lengthy, centres are dramatically overcrowded , allowing rare diseases to spread in at least one case. Asylum seekers lack even the most basic amenities and have been unable to eat or sleep .

The Home Office is unprepared, and spending FCDO’s money

Asylum seekers are generally housed in initial accommodation centres when they arrive, before moving into ‘dispersed’ accommodation (housing throughout the UK) while their claims are assessed. However, these centres became overwhelmed as channel crossings increased, and at the same time, a court ruling found that the Home Office could not cease providing accommodation support when refugees were at risk of homelessness during the pandemic (previously, they frequently made asylum seekers homeless ). While positive, the Home Office was not prepared for the impact of this, and many asylum seekers were moved to hotels as a result, at great cost.

Underlying this is an issue of accountability. As was pointed out in a recent International Development Committee meeting , because in-donor refugee costs are all from the ODA budget, the Home Office is essentially spending FCDO’s money. They have very little incentive to try and control costs because any emergency expenditure required will not eat into their own programmes, but simply absorb more of the FCDO-controlled aid budget.

Furthermore, despite frequent protestations that the UK is simply following the DAC rules (which allow only first year in-donor refugee costs to be included), it appears that the UK is counting more than just first year costs in some cases. The UK counts all initial accommodation costs (referred to as 'section 98' support ') as ODA on the basis that this is expected to last for “no longer than 28 days”. However, there are numerous cases of refugees remaining in initial accommodation for over a year. Added to this is 11 months of 'section 95' support . Whether this falls within a year depends on the degree of overlap, but given that the average length of time that asylum seekers have remained in initial accommodation has risen from around one month (as assumed in the UK’s methodology) to six months, it seems likely that some of these costs are overcounted.

The impact that this has on total in-donor refugee costs is almost certainly small, and not the cause of the increase. But the above methodology is not consistent with the “conservative approach” encouraged by the DAC . In addition, contrary to Andrew Mitchell claiming that the UK cannot “pick and choose ” which rules to follow, other countries do. Luxembourg and Australia have chosen not to count in-donor refugee costs for years. Four others chose not to count donations of excess Covid vaccines .

This problem will get worse before it gets better. Asylum applications continued to increase throughout 2021, but the associated costs are not necessarily included in the above figures. For a refugee arriving in 2021 Q4, the majority of costs will be incurred in 2022. Given arrival trends, in-donor refugee costs in 2022 would have been about two-thirds of the level in 2021 even if no asylum seekers had arrived in 2022. The approach is neither effective or sustainable and risks failing refugees in the UK and the world's poorest people – the very people ODA was intended to support.

Domestic concerns have taken money from the world’s poorest people

In response to the situation in Ukraine, the UK eventually realised that it was untenable to count all in-donor refugee costs under the self-imposed floor and ceiling of 0.5% of GNI, and allocated an additional £2.5 billion to the ODA budget over two years. But this only partially undoes the damage from counting the burgeoning costs of providing for refugees under an already squeezed aid budget. Initial accommodation costs alone have taken nearly £1 billion from the UK’s aid budget already, without having achieved much for refugees in the UK. It was right that the Home Office ceased making asylum-seekers homeless during the pandemic and the Home Office should continue to provide shelter for those in need, but this was a public health measure and had nothing to do with development, so shouldn’t impact the aid budget.

This illustrates the problem in sticking to a rigid ceiling to the ODA budget, especially when the FCDO is not fully in control, other departments have little incentive to control costs as they are not accountable for the ODA budget, and unpredictable spending items are included. The UK should remove in-donor refugee costs from the aid target, either by applying the target to a narrower measure of aid, or removing the costs from ODA completely. Neither Luxembourg nor Australia count them, and four countries have chosen not to count excess vaccine donations . They recognise that 'following the rules' is not a good excuse for behaviour that they see as unethical. The UK should follow suit.

This blog is part of a Development Initiatives series on debates concerning the rules for measuring official development assistance (ODA) , and potential reforms to its governing body, the Development Assistance Committee. ODA is the most widely used statistic on international aid, and how we measure it matters.

Case study: Sarah's experience of 'initial accommodation' in the UK's asylum system

These increasing costs aren't necessarily reflected in the experiences of asylum seekers who come to the UK. Government policies can have very human consequences. DI spoke to Sarah [not her real name], a musician and refugee who fled Iran in fear of her life. She related her experience to us, and it corroborated the numerous stories reported in the media.

Sarah is from Iran. After arrival in the UK, she says she was sent to a hotel for one night and stayed there for seven months. After that she was moved around, sometimes with only one day's notice, and not knowing where she was.

In that first hotel, she told us she had no cooking facilities and the accommodation could not accommodate any dietary requirements. She shared a single washing machine with hundreds of others, and was not allowed visits from friends or family. She received support of only £8 per week and was unable to work (which has been long criticised by campaigners). Sarah was essentially trapped in this hotel, which she described as “like prison”. She says she knew others who had been in this situation for much longer, some for over a year.

Notes

- 1 In the rules governing ODA, the word 'refugees' is used to refer to both approved refugees and those seeking asylum. In the UK case, the majority of costs are associated with the latter.

- 2 Asylum applications and resettlement figures combined increased by 18% between 2019 and 2021. However, for those arriving in Q4 2020 (for example), most of the costs will fall in 2021. When this is adjusted for, there was a fall of 9%.

- 3 This is possibly an underestimate as some Home Office projects have had information removed.

Related content

Counting excess vaccine donations as ODA inflated aid in 2021: Here's why they still shouldn't count

DI's Euan Ritchie explains how donors counted vaccines as ODA in 2021, and why the current OECD DAC rules on counting vaccines should change to stop inflating aid

The DAC debates: why aid measurement matters for development

The way we measure aid affects the type and quantity provided as well as our perceptions of it. Why are the DAC's rules controversial?

Should lending special drawing rights (SDRs) count as aid?

Rechanneling special drawing rights to low- and middle-income countries is an elegant solution to address global problems. Using them as an excuse to cut aid elsewhere is self-defeating.