Data disharmony: How can donors better act on their commitments?

This briefing highlights key challenges emerging from our work analysing national data ecosystems, and aims to promote discussion between relevant stakeholders on how best to overcome these.

DownloadsIntroduction

This is the second in a series of discussion papers we are publishing to highlight key challenges emerging from our work analysing national data ecosystems, with the aim of promoting discussion between relevant stakeholders on how best to overcome these. In our first paper The data side of leaving no one behind [1] we looked at the challenges facing data ecosystems in low- and middle-income countries. We concluded that “…governments need to own their own problems and solutions. They need to own their own data on behalf of their citizens. And for this to be sustainable they need to finance it.” [2]

This is currently not the case in most countries. Financing available for investment in data infrastructures and statistical production remains insufficient. It has been estimated that in 2015 low- and middle-income countries had a gross annual requirement of about US$3 billion to meet their data and statistical needs, of which only one half was being met by domestic resources. [3] In 2018 donors contributed US$693 million, [4] leaving a funding gap of a similar amount. Donors thus continue to play an important and disproportionate role in the financing of this ecosystem. Their decisions on how they both select and deliver their investments have significant impact on the political economy of data.

This paper examines the role of donors investment in national data ecosystems, focusing in particular on the challenges of harmonisation. As with our first paper, the issues we describe here are not new – they are well-known and have been recognised by donors themselves over many years. Rather than simply re-stating the problem, the purpose of this paper to promote an open discussion about why – given longstanding commitments to address these issues – progress has been limited, and what both donors and national governments can do to overcome the challenges of harmonisation in order to maximise the impact of their investments in national data systems.

Recently our business development team at Development Initiatives presented us, in the same week, with two contract opportunities. The first was to “conduct a mapping of the Kenya Innovation Ecosystem.” [5] The second was to provide “a synthesis of existing evidence on the evolution of the Kenyan start-up ecosystem.” [6] This wasn’t an unusual coincidence; it happens all the time. Which begs the question: are national governments and donors making the best use of limited resources?

In this paper we focus on data investments, but this is only a small part of a bigger story.

Two decades of commitments

In March 2002 over 50 heads of state gathered in Mexico to discuss key issues relating to global development. [7] They agreed on the Monterrey Consensus: a commitment to rationalise a range of activities covering international finance and trade. One of the commitments was to make aid (also known as official development assistance; ODA) more effective through intensifying efforts to:

“Harmonize their operational procedures at the highest standard so as to reduce transaction costs and make ODA disbursement and delivery more flexible, taking into account national development needs and objectives under the ownership of the recipient country.”

United Nations, 2002. Monterrey Consensus on Financing for Development. Available at: https://www.un.org/esa/ffd/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/MonterreyConsensus.pdf

The Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the OECD set up a task force to address these issues, which undertook a needs assessment survey in 11 developing countries. Each survey respondent was asked to name the three most important obstacles to effective aid delivery. The most common responses were:

- Donor-driven priorities and systems : The pressure donors bring to bear on partners’ development policies and strategies.

- Difficulties with donor procedures : Overcomplicated donor procurement.

- Uncoordinated donor practices : Competing donor systems making duplicative demands on partners’ administrations. [8]

In February 2003 more than 40 bilateral and multilateral institutions met in Italy for the First High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness [9] and endorsed the Rome Declaration on Harmonisation. In it they recognised that many of their efforts were “generating unproductive transaction costs”, that their practices did not always “fit well with national development priorities” and they therefore committed to a range of practices to enhance harmonisation. These included:

- Ensuring that development assistance is delivered in accordance with partner country priorities

- Reviewing and identifying ways to amend, as appropriate, our individual institutions’ and countries’ policies, procedures and practices to facilitate harmonisation

- Intensifying donor efforts to work through delegated cooperation at the country level. [10]

The 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness built upon the Rome Declaration on Harmonisation with a focus on ownership, harmonisation, alignment, results and mutual accountability. [11] These commitments were repeated in the next two high level forums – in Accra in 2008 [12] and in Busan in 2011 [13] – and continued in a similar format [14] at the high-level meetings of the Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation (GPEDC) in Mexico in 2014, [15] Nairobi in 2016 [16] and New York in 2019. [17]

Progress in meeting these commitments continues to be slow. A 2011 study concluded that “aid fragmentation persisted after the Paris Declaration and coordination among donors has even weakened.” [18] The GPEDC’s own 2019 Monitoring Report found that the “alignment of development partner projects to partner country objectives, results indicators, statistics and monitoring systems is declining.” [19]

“The literature on aid effectiveness is replete with critiques of these donor commitments. For example, a 2018 paper reporting on a survey of 150 health workers in Ethiopia, Nigeria and India finds that ‘Despite wide acknowledgment of the importance of harmonisation, our respondents reported perennial problems making it difficult to achieve in practice. These included the large number of donors and implementers working on parallel innovations and programmes, the continued focus on ‘vertical’ project funding, and donors’ competing interests, priorities and ways of working’.”

Wickremasinghe D., et al. “It’s About the Idea Hitting the Bull’s Eye": How Aid Effectiveness Can Catalyse the Scale-up of Health Innovations. Int J Health Policy Manag, 7(8), 2018, 718–727. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6077277/

Our experiences working across seven countries bear this out. [20] Below we highlight three issues that we came across with regularity: the duplication of effort in competing household surveys; the duplication of investments in administrative systems; and national data governance and infrastructures not being followed by the humanitarian community.

Duplicating household surveys

In the absence of reliable administrative data, household surveys continue to play a critical role in low- and middle-income countries. Advances made in the implementation of mobile-based surveys during the Covid-19 pandemic have breathed new life into the format. While, as we argued in our first paper, the affordable level of geographic disaggregation available to most surveys renders them of limited use to planning and monitoring at the point of service delivery, they remain essential sources in many countries.

UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) and the USAID-funded Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) [21] remain the most widely used sources of socioeconomic (and Sustainable Development Goal; SDG) statistics in many countries. [22] Our 2016 paper comparing these two surveys found that two-thirds of the questions are either identical or similar enough to be practically comparable. [23] Even where similar, differences in the structure and syntax of the microdata makes it very difficult to compare or merge DHS and MICS data.

Over the past decade 105 DHS and MICS surveys have been conducted in 42 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, and 20 countries have conducted both surveys (see Appendix 1 for details). Is there a reason why so many countries run both surveys, despite their similarities, rather than investing in the continuity of just one?

Yes. Firstly, they cost nothing to the country because they are fully donor funded; in fact in many countries survey financing contributes to the national statistics office wage bill. Secondly, as they are expensive to run, donors typically fund them in five-year cycles, so interspersing the two provides more regular coverage. Thirdly, they are often managed by competing national institutions. In Nigeria, for example, MICS is conducted by the National Bureau of Statistics [24] and DHS by the National Population Commission. [25] It appears that no attempt has been made to merge or compare the data between surveys. Similarly, in Bangladesh MICS is conducted by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics [26] and DHS by the National Institute of Population Research and Training. [27] It seems the two institutions have no systematic mechanism for collaborating or sharing, and they seldom do. [28]

In March 2015 the World Bank submitted a report on improving household surveys to the UN Statistical Commission (UNSC). Its diagnosis was blunt:

“The fragmentation of efforts, self-interest and poor coordination and harmonization of standards across stakeholders is symptomatic of the absence of a proper institutional framework to support a renewed household survey agenda.”

UN Economic and Social Council, 2015. Report of the World Bank on improving household surveys in the post-2015 development era: issues and recommendations for a shared agenda. E/CN.3/2015/10. Available at: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/doc15/2015-10-HouseholdSurveys-E.pdf

This resulted in the formation of the Intersecretariat Working Group on Household Surveys (IWGHS), [29] one of its aims being to “promote coordination and cooperation in the planning, funding and implementation of household surveys.” [30]

Five years on, in its report back to the 2021 UNSC, the IWGHS revealed that limited progress had been made, stating only that “with the objective of fostering the coordination of household survey operations, two task forces were established…” [31]

Not only has little progress been made, but in a background paper submitted to the 2019 UNSC the secretariat argued that:

“Alternating surveys with similar content and coverage can reduce redundancies in data collection, especially on indicators that do not change rapidly. For instance, in several countries, such as Nigeria and Ghana, MICS and DHS surveys are alternated, creating a steady set of trend data on comparable indicators, thus broadening the overall data landscape.”

Intersecretariat Working Group on Household Surveys, 2019. Achieving the Full Potential of Household Surveys in the SDG Era. Available at: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/50th-session/documents/BG-Item4c-ISWGHS-E.pdf

As mentioned above, we learnt first-hand in both Nigeria and Bangladesh that MICS and DHS data is not joined up. Were it to be made interoperable, this could at least help to move data out of silos.

DHS and MICS are the most widely used surveys, but there are many more. Between 2009 and 2018, 33 different surveys were conducted in Zimbabwe, [32] supported by 12 different donors. [33] Only three of these surveys were disaggregated to district level to be of use to local government and service delivery agencies (see Table 2 in the Appendix for details).

There are reasons why countries are conducting multiple one-off, small-sample surveys. Firstly, because this is what donors are offering. Secondly, in Zimbabwe at least, the US$50 daily stipends offered to statisticians for field work support staff incomes and can help retain staff.

Multiple surveys, particularly in the absence of a well-organised national indicator framework, lead inevitably to a duplication of effort. We came across an example in Bangladesh. Between 2013 and 2019, six surveys and two administrative systems collected data for SDG indicator 3.1.2 – the proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel. The observed results ranged from 32% to 85% (see Table 3 in the Appendix).

Duplicating administrative systems

The development of registries and management information systems are in their early stages in most low- and middle-income countries, yet here there is also widespread duplication of effort.

In Bangladesh the main Health Management Information System is DHIS2 [34] and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare also maintains a Family Planning Management Information System (FPMIS). Large amounts of data in the two systems are the same. USAID was instrumental in establishing FPIMS and remains its principal funder; UNICEF is the principal funder of DHIS2. The Directorate General of Health Services manages one system, and the Directorate General of Family Planning manages the other. Each system does collect some unique data, which is of use to the other directorate, but data is not regularly or systematically shared between the two systems. In short, the systems overlap but are not interoperable. [35] These systems have been developed in line with different donor priorities, which has created tensions between two internal departments.

In Nepal the Building Information Platform Against Disaster [36] was developed with donor funding despite the existing Disaster Risk Reduction Portal [37] producing timely data throughout the country’s police infrastructure.

.To manage health services for Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh a modified DHIS2 module was developed. Nevertheless, the World Health Organization deployed its Early Warning, Alert and Response System (EWARS), which duplicates the DHIS2 data. In 2017 a study led by the World Health Organization recommended that DHIS2 is not suitable for humanitarian operations as it is dependent on national information and communications technology (ICT) infrastructures and expertise. [38] What the study failed to acknowledge that DHIS2 is already well established in many countries in such circumstances humanitarians need to implement their commitments to strengthen the humanitarian-development nexus. [39]

A 2018 study focusing on the compilation of lists of health facilities in Nigeria [40] found that, between 2011 and 2016, five donors [41] funded 10 separate but similar exercises. [42] The study concludes that:

“Though it is well documented that aid fragmentation and poor coordination deters aid effectiveness in recipient countries, evidence continues to show that donor commitment to better coordination are yet to be achieved. Our analysis of the health facility listing projects revealed that duplication of effort persists in Nigeria.”

In Uganda the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development maintains several overlapping data systems, which presents challenges in terms of coordination and management issues, lack of capacity, reporting and tracking of child protection statistical indicators, gender-based and child violence cases. It is not uncommon for the same data to be keyed into two different systems, each supported by a different donor. [43]

What happens when a new system surpasses an older one? The Child Protection Information System (CPIMS+) started life as a case management tool for field workers, but it has in recent years grown in both robustness and usefulness and is being scaled up for national usage. In Nigeria it has overtaken the National OVC Management Information System (NOMIS). There is now significant overlap between CPMIS+ (funded by UNFPA and UNICEF) and NOMIS (developed by Family Health International 360’s Global HIV/AIDS Initiative Nigeria with USAID support). Both systems continue to operate rather than seeking a complementary solution to this duplication.

In 2019 Development Initiatives conducted a study on the proliferation of systems involved in the validation of cash transfer beneficiaries in Somalia. It found that the politics of ownership and control over access to data prevented collaborative efforts by humanitarian agencies to harmonise data systems and that the lack of a common stance among donors led to uncoordinated efforts. Paradoxically the study found that the fear of the potential disruptions that the process of improving harmonisation might cause to current operations was a key reason for blocking a joined-up, sustainable solution. [44]

In a 2021 paper, the OECD highlights the lack of harmonisation among an increasing number of development actors engaged in uncoordinated interventions:

“In Ethiopia, for example, we found that development partners were using 40 different indicators to measure SDG 7.1.1 on access to electricity. This made their data unharmonised, prevented further cooperation and left the Ethiopian government without a clear picture of how many households had access to electricity across the country.”

OECD, 2021. Achieving SDG Results in Development Co-operation: Summary for Policy Makers. Available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/achieving-sdg-results-in-development-co-operation_5b2b0ee8-en

This observation is not only disappointing in terms of the scale of fragmentation, but surprising in that it assumes that SDG monitoring is the responsibility of development partners, rather than the government.

The latest Partner Report on Support to Statistics highlights another aspect of fragmentation. [45] An increasing proportion of support for data and statistics is being delivered as a partial element of broader programmes, rather than through dedicated projects. While this may be good for extending the breadth of data investments, the fact that the investment is tied to a broader objective makes it harder to influence its alignment to national objectives. And while donors may attempt to ensure that their broader programmes do not duplicate effort, there is unlikely to be coordinated scrutiny of components.

Maintaining parallel data universes

Humanitarian agencies are often deployed into emergency situations at short notice. They need fast access to timely operational data, which is often not available and so they establish their own data infrastructures. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) the average humanitarian crisis now lasts more than nine years. [46] The implications of the increasing duration of crises was recognised at the World Humanitarian Summit in 2016 by the Grand Bargain in its call for its signatories to: enhance engagement between humanitarian and development actors; support and complement national coordination mechanisms; and increase and support multi-year investment in the institutional capacities of local and national responders. [47] The response to this call has been limited.

In Bangladesh we found that competition between UN agencies [48] supporting the Rohingya refugees led to limited data sharing between agencies, let alone with the government. [49]

In South Sudan we found a marked difference in the way that government officials perceive the data challenges facing the country and the perceptions of donors and humanitarian actors. Many humanitarian actors consider the government to be too weak to undertake most forms of data collection and analysis. Government officials, on the other hand, while acknowledging their limitations, believe that this is often used by humanitarians as justification to circumvent the government on the implementation of key humanitarian and development programmes. [50]

In many countries the UN Resident Coordinator’s Office has established a data working group to bring together its agencies to both share information and collaborate on data projects. In Nigeria we found that the group had not met − while in Bangladesh we observed meetings used to ‘show and tell’ work rather than to collaborate. [51]

A 2019 study by the Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility in South Sudan recommended that:

“…donors and agencies must understand, and where appropriate, work within South Sudanese systems, rather than ignoring or overriding them. The aid community needs to acknowledge that for many South Sudanese these local systems of accountability are legitimate, respected and understood, and that it is the international system that is alien and unintelligible.”

Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility, 2020. Lost in Translation: The interaction between international humanitarian aid and South Sudanese accountability systems. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Lost-in-Translation-The-Interaction-Between-International-Aid-and-South-Sudanese-Accountability-Systems-Final-1.pdf

In Somalia, a recent study of the role of donors and aid agencies in collecting data found that:

“the role of the state in defining the research agenda, monitoring existing data collection by international actors, and regulating knowledge production more broadly remains rudimentary” and concluded that “the current situation in which international aid agencies and consultancy firms dominate knowledge production without sharing the data with the wider Somali public is not sustainable.”

Somalia Public Agenda, 2021. Who owns data in Somalia? Ending the country’s privatised knowledge Economy. Available at: https://somalipublicagenda.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/SPA_Governance_Briefs_12_2021_ENGLISH-1.pdf

A blunter view was expressed by an experienced policy adviser:

“The system holds back the emergence of national humanitarian organizations and national political agreements on humanitarian social contracts within crisis affected societies. The international bias in the system is, therefore, politically and personally offensive.”

Slim H. Localization is Self-Determination. Front Polit Sci, 2021, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.708584/full

Funding decisions

Tracking how donors fund data infrastructures is a complicated business as there is no agreement as to what is or isn’t included in the ‘sector’ and how it is coded. The fact that the World Bank’s first fund, the Trust Fund for Statistical Capacity Building (TFSCB), [52] established in 1999, was in 2021 replaced by a renamed Global Data Facility (GDF) [53] is indicative of the changing scope.

Not too long ago, before the ‘data revolution’, official statistics and the national statistical system were solely the responsibility of a country’s national statistics office. Generally speaking, national statistics offices were then conservative institutions, responsible for macro-economic statistics and demographics. Censuses and surveys were their stock in trade. Financing of a single institution, with a single budget (met by a mix of domestic and international resources), was relatively easy to track.

This landscape is, however, in a state of rapid flux. Management information systems – central databases relying on localised data collection – now deliver civil registration; national identity; population, building and business registers; and health and education systems, managing the data of both facilities and individuals. New technologies enable more rapid and responsive data collection, storage, analysis and distribution. But with this diversity and breadth comes an even bigger need for coordination and collaboration.

Most experts would agree that administrative data is the future. Yet it remains very difficult to accurately track and coordinate the investments being committed to these systems. The purpose codes maintained by the OECD Creditor Reporting System – mirrored by the International Aid Transparency Initiative and used by PARIS21’s annual Partner Report on Support to Statistics (PRESS) – allow for the classification of statistical capacity building but not for other data-specific investments.

For the first time, in the new Clearinghouse for Financing Development Data, [54] a serious attempt is being made to itemise line ministry planning and budgeting on administrative data (see Figure 1 for a snapshot). This methodology will take time to mature but it is positive that there is now a concerted effort to provide visibility of the entire official data landscape.

Figure 1: Snapshot of line ministry data needs

|

Ministry

of Agriculture and Animal Resources |

||

|---|---|---|

| Detailed information | ||

| Projects | ||

| ► Agriculture Management Information System (AMIS) | Project timeline: 2018−2024 | |

|

► Agriculture

Commoditied Market price Information System (eSoko) |

Project timeline: 2019−2024 | |

|

► Comprehensive Food

Security and Vulnerability and Nutrition Analysis Survey (CFSVA) |

Project timeline: 2018−2021 | |

|

► Women’s Empowerment

in Agriculture Index (WEAI) |

Project timeline: 2020−2022 |

Source: Clearinghouse for Financing Development Data

One of the suggested benefits of the Clearinghouse is the ability for donors to coordinate their activities through an understanding of what each other is funding. This is hardly a novel idea. For over two decades retrospective data has been available through the OECD. [55] Nowadays most major donors publish details of current financing activities, no more than a few months retrospectively, through the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI). [56] And prior to IATI data reaching a critical mass some countries maintained their own Aid Information Management Systems. Yet visibility of each other’s activities appears to have had little impact on coordination between donors.

If the channelling of bilateral money through multilateral funds is thought to be a solution to a harmonious approach, the jury remains out. The new Global Data Facility is yet to receive pledges. Its predecessor, the TFSCB, failed to attract widespread support and was largely reliant on contributions from the UK. A 2017 report on the fund highlighted the dangers of reliance on a single source:

“As a case in point, the recent DFID contribution of $ 20 million was earmarked for data production in household surveys. While this purpose was certainly in alignment with World Bank concerns about the lack of respective data from low capacity countries, a situation could arise where DFID goals in this respect would not be completely in line with TFSCB funding objectives. Attached contributions by a major donor can carry the risk of changing the remit of the TFSCB from its original or core goals if this major donor is responsible for almost the entire TFSCB budget.”

The Advisory Panel of the World Bank’s Trust Fund for Statistical Capacity Building, 2017. Report of the Fourteenth Meeting of the TFSCB Advisory Panel. Available at: https://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/421301493936349083/pdf/TFSCB-APs-report-Final-version.pdf

The Global Data Facility will be governed by a partnership council composed of representatives from the World Bank and each contributing donor. Other stakeholders may be invited to council meetings and to a technical advisory group, [57] but funding decisions may be led by bilateral council members’ competing interests rather than the priorities of their recipients.

Competing interests

The Rome Declaration on Harmonisation commits donors to “ensuring that development assistance is delivered in accordance with partner country priorities”. Is this achievable? A study reviewing the first five years of the aid effectiveness agenda observed that “the failure of donors to keep the promises made in the Paris Declaration arguably reflects the complex political economy of the international aid system.” [58]

The US Agency for International Development has this priority:

“USAID development policy supports the objectives of the National Security Strategy and other strategic documents, such as the Department of State-USAID Joint Strategic Plan, that aim to strengthen our diplomatic and development capabilities to better meet our foreign policy goals.”

USAID. Policy. Available at: https://www.usaid.gov/results-and-data/planning/policy

The UK Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) operates within this strategy:

“ODA is a vital, essential, and absolutely indispensable element of [the Integrated Review] strategic approach. But, to maximise its effectiveness, it must be used in combination with our development policy expertise, our security deployments and support abroad.”

Gov.uk, 2020. Official Development Assistance: Foreign Secretary's statement, November 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/official-development-assistance-foreign-secretarys-statement-november-2020

According to a recent study:

“Concerns have also been raised that with humanitarian and development concerns more explicitly intertwined with UK national interest in the new FCDO there will be even less political incentive to ceding power to “other” (local) actors.”

Goodwin E. and Ager A. Localisation in the Context of UK Government Engagement with the Humanitarian Reform Agenda. Front Polit Sci, 2021, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.687063/full

A programme of the UK Office of National Statistics aimed at modernising official statistics in Africa [59] includes in its aims “establishing international influence for HMG priorities”. [60]

The World Bank does not have geopolitical interests, but it does have a firm opinion on delivering its own “proven solutions that integrate the WBG's development knowledge and financial services.” [61]

In other words, donors have very clear ideas on what they seek to deliver. But their approaches need to be flexible to different country priorities and they need to listen to their recipients, rather than the other way round.

Is harmony possible?

After 20 years, donors are no closer to meeting their commitments. But it is unrealistic to place the onus solely on developing countries as the chronic underfunding they are responsible for places them on the wrong side of the power balance. The diagnosis is stark and the prognosis is vague.

Country collaborations

One possibility for bridging this gap could be achieved through the development partner forums that exist in most developing countries. These are monthly or quarterly meetings where donors and international agencies meet with their government counterparts to discuss matters of mutual interest. These forums are not without their tensions [62] and superficial formalities. The less governments invest in their own infrastructures, the greater the power imbalance that characterises these meetings.

Rebooting these forums is worth an attempt. Those donors who are members of IATI should be galvanised to champion the value of timely, transparent data on development priorities: both intentions (captured in IATI through forward-looking budgets) and actual spend. This data provides both donors and governments with the timely evidence required for harmonised discussions and joined-up decisions. Unlike OECD data, which can be up to two years old at the time of publication, IATI data can be viewed up to only a quarter in arrears.

Even where development partner forums meet regularly, the balance of power between donors and government, particularly in lower income and fragile countries, can easily intimidate government officials into silence. Regional and continental bodies (such as the African Union and Economic Commission for Africa) have a role to play in encouraging and empowering their member governments to stand up and hold their development partners to account.

Levelling the financial playing field

There are two possible ways out of the power imbalance that clouds data investments. The first could take the form of a compact between donors and countries where donors commit to only funding capital investments and that such investments are conditional on the recipient government formally committing to the ongoing maintenance of the resulting systems. This approach would tie every donor investment to specific government counterpart funding, reducing the likelihood of both duplication and misalignment to country priorities.

The original 2014 proposal for a compact between government and donor focused more on performance, but it established an approach that involved mutual accountability:

“Mobilize more donor funding through government-donor compacts and experiment with pay-for-performance agreements. Governments should press for more donor funding of national statistical systems, using a funding modality, or data compact, that creates incentives for greater progress and investment in good data. A pay-for-performance agreement could link funding directly to progress on improving the coverage, accuracy, and openness of core statistical products.”

Center for Global Development, 2014. Delivering on a Data Revolution in Sub-Saharan Africa. Available at: https://www.cgdev.org/publication/ft/delivering-data-revolution-sub-saharan-africa

A second option, rapidly gaining momentum, involves the transition from current aid architectures to a more equitable arrangement, Global Public Investment. [63] With this option all countries, high and low income, would contribute proportionately to a central fund that would disburse according to needs, as decided by all stakeholders. This is an established concept applying to much of EU funding.

“The vision at the heart of the EU’s “structural and investment funds” is not just poverty reduction, but convergence to a common standard, “narrow[ing] the development disparities among regions and member states”. Through these funds the EU has spent decades redistributing billions of Euros every year between its members.”

Glennie J. The Future of Aid: Global Public Investment. Routledge, 2020.

Mapping the data landscape transparently

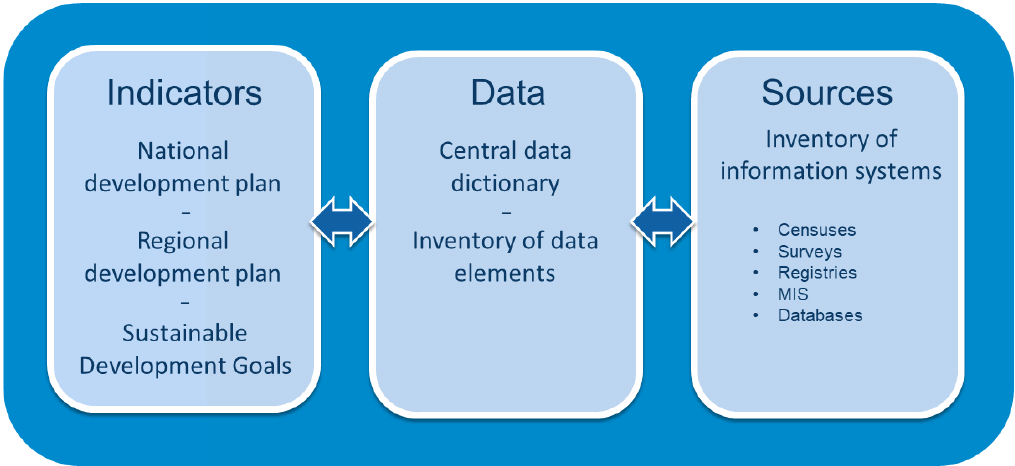

The greatest opportunity to create a level playing field and to resolve these problems lies, in our opinion, in improved and transparent data governance, with countries creating a transparent mapping of their available data against their statistical needs in a national indicator framework.

Their needs are defined by the indicators required for their national development plan, sector strategies and other national priorities, as well as their commitments to regional and global monitoring frameworks.

Most indicators are made up of a series of data elements that are manipulated according to agreed methodologies. A theoretical mapping of all indicators’ components results in a list of all required fields each with their own precise definitions, which should be stored in a central data dictionary .

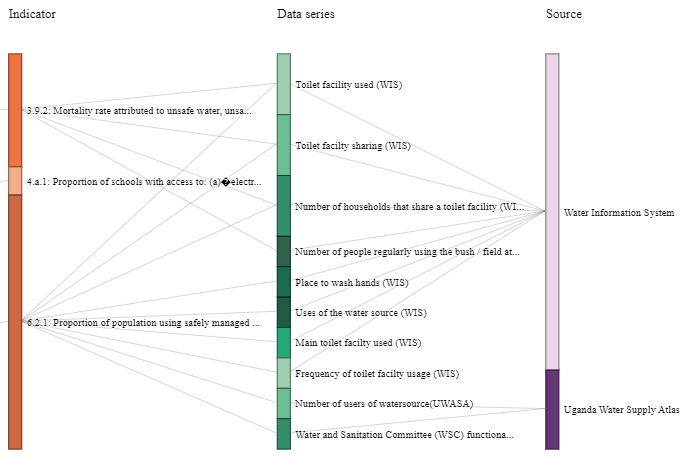

A complete inventory of information systems – from censuses and surveys to registries, administrative systems and other databases – also reveals a list of data elements that have been collected. The mapping from indicators back to sources (see Figure 2 for an example) will therefore reveal gaps (where data for an indicator is not available), duplications (where data is captured by more than one system) and redundancies (where data that is captured is never used).

Figure 2: Excerpt of Uganda indicator-to-source mapping

The image shows a sankey diagram as an example of indicator-to-source mapping. It maps from Sustainable Development Goal indicators back to sources via data series.

Source: Development Initiatives. The development data assessment. Available at:

Metadata captured for each of these exercises (see Table 6 in the Appendix for a summary of its possible content) facilitates in-depth analysis of the entire national data ecosystem in a way that is difficult to achieve otherwise.

Such a framework not only provides the national statistical system with a well-organised data governance infrastructure (Figure 3) but, critically, it allows all stakeholders to understand where gaps exist and where duplication of effort is taking place. Transparent data governance also ensures donors’ political intentions are explicit.

Figure 3: Data governance infrastructure

A diagram showing three elements of a data governance infrastructure and links between different areas. The first element shows data indicators, which include national development plans, regional development plans and Sustainable Development Goals. This is linked to the second area, data governance, which includes a central data dictionary and inventory of data elements. The third area is governance of data sources and this includes an inventory of information systems, within which sit censuses, surveys, registries, management information systems and databases.

Source: Development Initiatives.

Developing country governments are best placed to lead the way out of this problem. By deciding to manage their own prioritisation of investments, governments are in a far stronger position that they may appreciate. The first step on this journey is accepting that it is their problem to fix.

Appendix

Table 1: DHS and MICS surveys conducted in Africa since 2010

| Country | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angola | DHS | DHS | DHS | ||||||||||

| Benin | DHS | MICS | DHS | MICS | |||||||||

| Burkina Faso | DHS | DHS | |||||||||||

| Burundi | DHS | DHS | |||||||||||

| Cameroon | DHS | MICS | DHS | ||||||||||

| Central African Republic | MICS | MICS | MICS | ||||||||||

| Chad | MICS | DHS | MICS | ||||||||||

| Comoros | DHS | MICS | |||||||||||

| Congo (Brazzaville) | DHS | MICS | |||||||||||

| Congo (DRC) | MICS | DHS | MICS | ||||||||||

| Cote d'Ivoire | DHS | MICS | DHS | ||||||||||

| Equatorial Guinea | DHS | MICS | |||||||||||

| Eswatini | MICS | MICS | MICS | ||||||||||

| Ethiopia | DHS | DHS | DHS | ||||||||||

| Gabon | DHS | DHS | |||||||||||

| Gambia | MICS | DHS | MICS | DHS | |||||||||

| Ghana | DHS | MICS | |||||||||||

| Guinea | DHS | MICS | DHS | ||||||||||

| Guinea-Bissau | MICS | MICS | MICS | ||||||||||

| Kenya | DHS | DHS | DHS | ||||||||||

| Lesotho | DHS | MICS | DHS | ||||||||||

| Liberia | DHS | DHS | |||||||||||

| Madagascar | MICS | DHS | |||||||||||

| Malawi | DHS | MICS | |||||||||||

| Mali | DHS | MICS | DHS | ||||||||||

| Mozambique | DHS | DHS | |||||||||||

| Namibia | DHS | ||||||||||||

| Niger | DHS | ||||||||||||

| Nigeria | MICS | DHS | MICS | DHS | MICS | ||||||||

| Rwanda | DHS | DHS | |||||||||||

| São Tomé and Príncipe | MICS | ||||||||||||

| Senegal | DHS | DHS | DHS | DHS | DHS | DHS | DHS | DHS | |||||

| Sierra Leone | MICS | DHS | MICS | DHS | |||||||||

| Somalia | MICS | ||||||||||||

| South Africa | DHS | ||||||||||||

| South Sudan | MICS | ||||||||||||

| Sudan | MICS | MICS | |||||||||||

| Tanzania | DHS | DHS | |||||||||||

| Togo | MICS | DHS | MICS | ||||||||||

| Uganda | DHS | DHS | |||||||||||

| Zambia | DHS | DHS | |||||||||||

| Zimbabwe | DHS | MICS | DHS | MICS | DHS |

Sources: DHS Program, https://dhsprogram.com/Countries/, and UNICEF MICS, https://mics.unicef.org/surveys

Table 2: Surveys conducted in Zimbabwe between 2009 and 2018

| Latest | Name | Geographic disaggregation |

|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey | District |

| 2010 | Business Tendency Survey | Province |

| 2010 | ICT business surveys | Province |

| 2011 | Child Labour Survey (Part of Labour Force Surveys) | Province |

| 2011 | National baseline survey on life experiences of adolescents | Province |

| 2011 | Survey on violence against children | Province |

| 2012 | Census post enumeration survey | Province |

| 2013 | Zimbabwe Central Business Register Inquiry 2013 | Province |

| 2013 | Survey of Services | National |

| 2014 | Labour Force Surveys | Province |

| 2014 | Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey | Province |

| 2014 | Social Amenities Survey | Province |

| 2014 | Migration Survey (Part of Labour Force Surveys) | Province |

| 2014 | ICT household surveys | Province |

| 2014 | Financial Inclusion and Exclusion Survey | Province |

| 2015 | Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey | Province |

| 2015 | Volume of manufacturing surveys | Province |

| 2015 | Small Town WASH programme baseline survey | District |

| 2015 | Foreign Private Capital Survey Report | National |

| 2015 | Trade in Services Survey | National |

| 2015 | Agricultural and livestock surveys | Province |

| 2016 | Rural WASH survey | Province |

| 2016 | Waste and water statistics survey | Province |

| 2016 | Visitor Exit Survey | Province |

| 2017 | Rent and domestic workers surveys | Province |

| 2017 | School fees surveys | Province |

| 2017 | Poverty Income Consumption and Expenditure Survey | Province |

| 2017 | Inter-Censal Demographic Survey | Province |

| 2017 |

Census on ICT access and use by education institutions and health

facilities |

Province |

| 2017 | Infrastructure Statistics | Province |

| 2017 | Harmonised social cash transfers impact evaluation | District |

| 2018 | Consumer surveys | Province |

| 2018 | Domestic and outbound tourism survey | Province |

Source: Development Initiatives, unpublished research on behalf of UNICEF.

Table 3: Data collection for skilled attendance at birth indicator in Bangladesh

| System | Funding | Geographic disaggregation | Sample size | Year | Observed value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household surveys | |||||

| Utilization of Essential Service Delivery Survey | Division | 12,500 | 2013 | 34% | |

| Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey | USAID | Division | 19,000 | 2014 | 42% |

| Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey | UNICEF | District | 4,000 | 2019 | 59% |

| Coverage of Basic Social Services Survey | UNICEF | Upazilla | 216,000 | 2017 | 85% |

| Bangladesh Maternal Mortality and Health Care Survey | USAID / DFID | Upazilla | 298,000 | 2016 | 50% |

| Sample Vital Registration System | UNICEF / UNFPA | Upazilla | 298,000 | 2018 | 69% |

| Administrative systems | |||||

| District Health Information System | UNICEF | Facility | 2019 | 51−82% | |

| Family Planning Management Information System | USAID | Facility | 2019 | ? |

Table 4: Average annual commitments on aid to statistics by area of statistical activity (2009−2018)

| Domain | Average annual commitment (US$m) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic and social statistics | 161 | |

| Economic statistics | 104 | |

| Environment and multi-domain statistics | 45 | |

|

General statistical items and methodology of data

collection, processing, dissemination and analysis |

172 | |

|

Strategic and managerial issues of official

statistics at national and international level |

113 | |

| Average Annual Aid to Statistics | 597 |

Source: Development Initiatives, Aggregation based on PRESS 2019. https://paris21.org/press-2019

Table 5: Timeline of donor commitments

| 2002 |

Monterrey Consensus of the International Conference

on Financing for Development |

|

| 2003 | Rome Declaration on Harmonisation | |

| 2005 | Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness | |

| 2008 | Accra Agenda for Action | |

| 2009 |

Doha Declaration on Financing for

Development |

|

| 2011 |

The Busan Partnership for Effective

Development Co-operation |

|

| 2014 |

GPEDC Mexico High Level Meeting

Communiqué |

|

| 2015 | Addis Ababa Action Agenda | |

| 2016 | GPEDC Nairobi Outcome Document |

Table 6: Metadata for indicator frameworks

| Indicator | Data element | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Name | Name | Name |

| Definition / method of computation | Definition | Owner / Funder / Collector |

| Data elements | Source | Type |

| Rationale and interpretation | Unit | Primary / Secondary data |

| Sources and data collection | Sector | Statistical Sector |

| Disaggregation | Data Type | Official statistics? |

| Comments and limitations | Point of collection | Sample size (%) |

| Supplementary information | Scope / Geographic coverage (%) | |

| Responsible entities | Level of disaggregation | |

| Current data availability | Frequency | |

| Latest / Next / Previous | ||

| Time lag | ||

| Access | ||

| Data / metadata u.r.l |

Source: Indicator metadata based on SDG metadata database. Data element and source data based on Development Initiatives’ Uganda’s data ecosystem. Available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/ and /resources/ugandas-data-ecosystem/

Downloads

Notes

-

1

Development Initiatives, 2021. The data side of leaving no one behind: Lessons from landscaping. https://www.devinit.org/resources/data-side-leaving-no-one-behind/Return to source text

-

2

Development Initiatives, 2021. The data side of leaving no one behind: Lessons from landscaping. https://www.devinit.org/resources/data-side-leaving-no-one-behind/Return to source text

-

3

Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data, 2018. Making the case: More and Better Financing for Development Data. Available at: https://www.data4sdgs.org/sites/default/files/2018-03/Financing%20for%20Development%20Data%20Pamphlet%20FINAL_27Mar.pdfReturn to source text

-

4

PARIS21, 2021. Partner Report on Support to Statistics (PRESS) 2020: Under COVID-19, worrying stagnation in funding despite growing data demand. Available at: https://paris21.org/news-center/news/press2020-under-covid-19-worrying-stagnation-funding-despite-growing-data-demandReturn to source text

-

5

UNDP in Kenya and Government of Kenya, 2021. Request for proposal: Consultancy firm to consultancy firm to conduct a mapping of the Kenya Innovation Ecosystem.’ Available at: https://procurement-notices.undp.org/view_file.cfm?doc_id=270693Return to source text

Related content

Inequality: Global trends

This factsheet presents and interprets recent trends in levels of inequality globally using a number of different datasets.

The data side of leaving no one behind

In this paper we look at lessons learned from data landscaping at the national level, and examine how it can be used to inform decisions about poverty eradication and ensure no one is left behind.

Digital civil registration and legal identity systems: A joined-up approach to leave no one behind

An overview of trends in civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS). To deliver the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), how can we ensure everyone is counted?