Merging DFID and the FCO: Implications for UK aid

Analysis of what merging DFID and the FCO could mean for UK aid on poverty targeting, transparency and effectiveness, and recommendations for the new department.

DownloadsIntroduction

On 16 June 2020, the UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) would be merged into the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) to form a new Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office . This department will be led by the Foreign Secretary, with likely no separate Cabinet-level representation on development.

The UK Prime Minister has explicitly stated the need for aid to be spent in the national interest. This means we are likely to see a reorientation of aid spending towards the priorities of the FCO rather than those of DFID when they merge. Crucially, legislation that binds DFID to spend aid in a way that is likely to contribute to a reduction in poverty does not clearly apply to other departments , which just need to satisfy the OECD’s definition: to promote the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective and be concessional. With UK aid projected to fall as the UK economy contracts due to the impact of Covid-19, it is also pertinent that cuts in aid spending will be directed by this new department and dictated by its agenda.

Providing analysis of how each department has allocated bilateral country aid [1] over the last five years, this briefing sheds light on how the UK’s role in global poverty eradication would change if future allocations align closer to the priorities of the FCO rather than DFID. The analysis details how aid has been allocated by each department based on recipient countries’ income levels, extreme poverty levels, fragility and public domestic resources per capita to show that DFID allocates aid to where need is greatest, in stark contrast to the FCO. It also looks at DFID’s track record on tackling marginalisation with its focus on gender, disability and the principle of leaving no one behind. DFID has also been a global leader on aid effectiveness and transparency, priorities that are not reflected in the FCO’s aid spending.

Based on this, the briefing details the risks of following the FCO’s priorities and approach, and makes recommendations on how the UK government should retain the high standards and clear principles set by DFID, which have underpinned UK Aid’s achievements over the last 23 years and made the country a global leader on international development.

How does aid spending by DFID and the FCO compare?

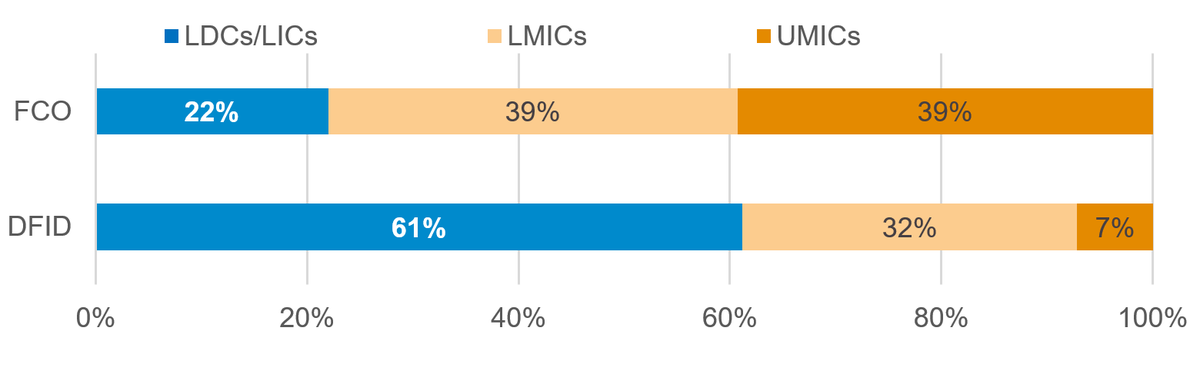

DFID allocates significantly more aid to low-income and least developed countries than the FCO

Looking at aid disbursed over the 2014–2018 based on recipient country income, DFID allocates well over half its disbursements to low-income and least developed countries, compared to just 22% of the FCO’s aid. In fact, the vast majority (78%) of the FCO’s aid goes to middle-income countries.

Figure 1: Proportion of DFID and the FCO's aid targeted at low income and least developed countries

Proportion of DFID and FCO aid targeted at low income and least developed countries

Source: Development Initiatives based on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC).

Notes: Data is for the five years to 2018 (latest year for which disaggregated ODA data is currently available). Abbreviations: LDC: least developed country; LMIC: lower-middle-income country; MIC: middle-income country; UMIC: upper-middle-income country.

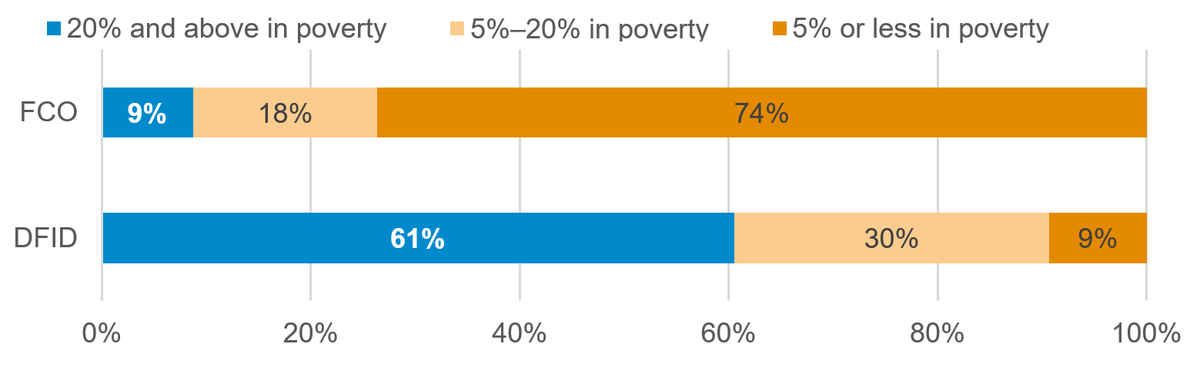

DFID heavily focuses its aid spending on countries with the highest levels of poverty; this contrasts starkly with the FCO, which prioritises aid spending on countries where poverty is lowest

The FCO provides 74% of its aid allocations to countries where less than 5% of the population live in extreme poverty. A tiny proportion, just 9%, goes to where poverty levels are high (over 20% of the population). By contrast, DFID allocates the largest proportion of its aid to where poverty is highest: 61% of allocations go to where over 20% of the population is living in extreme poverty. Just 9% of DFID’s aid goes to where extreme poverty is less than 5%.

Figure 2: Proportion of DFID and the FCO's aid disbursed to countries with high extreme poverty levels (% of population)

Proportion of DFID and FCO aid disbursed to countries with high extreme poverty levels (% of population)

Source: Development Initiatives based on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) and World Bank PovcalNet.

Notes: Data is for the five years to 2018 (latest year for which disaggregated ODA data is currently available). Poverty data for 2018 is not available and 2015 data is substituted as the most recent available comprehensive data. Countries for which no poverty data is available have been excluded. People living in extreme poverty are defined as living on less than PPP$1.90 a day.

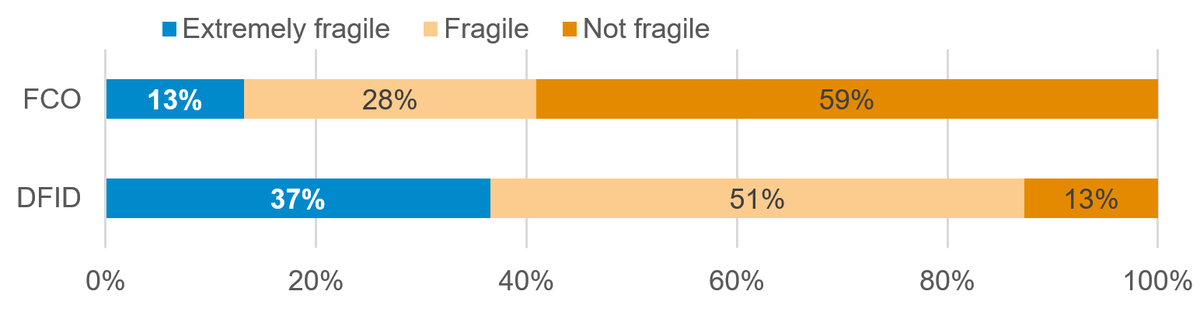

The majority of DFID aid goes to fragile states, whereas most of the FCO’s aid does not

Aid allocations based on countries’ fragility shows the biggest contrast in priorities between the two departments. While 88% of DFID aid goes to fragile states, the FCO’s allocations are less than half this proportion: 41%. DFID’s aid is also substantially more focused on the most fragile countries – which receive 37% of its aid allocations, compared with just 13% from the FCO. DFID is committed to spending 50% of its aid in fragile states ; however, this commitment will not automatically apply once the departments merge.

Figure 3: Proportion of DFID and the FCO's aid targeted at fragile countries

Proportion of DFID and FCO aid targeted at fragile countries

Source: Development Initiatives based on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC)

Note: Data is for the 5 years to 2018 (latest year for which disaggregated ODA data is currently available). Fragility categories are taken from OECD States of Fragility 2018 report.

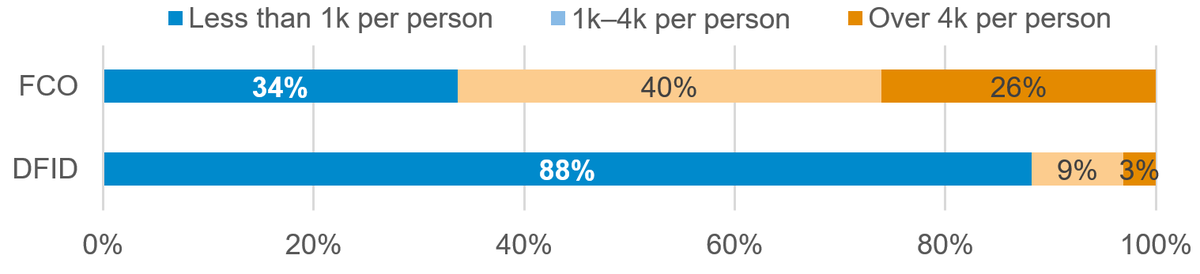

DFID heavily prioritises the countries with the least resources, whereas the FCO gives more aid to countries that have much higher government revenue per capita

DFID allocates 88% of its aid spending to countries with less than US$1,000 per capita in domestic resources. The FCO’s allocations are much more evenly spread, but countries with higher per capita government revenue over US$1,000 receive the highest proportion of the department’s aid spending.

Figure 4: Proportion of DFID and FCO aid targeted at countries with the lowest revenue per capita

Proportion of DFID and FCO aid targeted at countries with the lowest revenue per capita

Source: Development Initiatives based on Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) World Economic Outlook database and IMF Article IV Staff and programme review reports (various)

Note: ODA data is for the five years to 2018 (latest year for which disaggregated ODA data is currently available). Countries for which no government revenue data is available have been excluded.

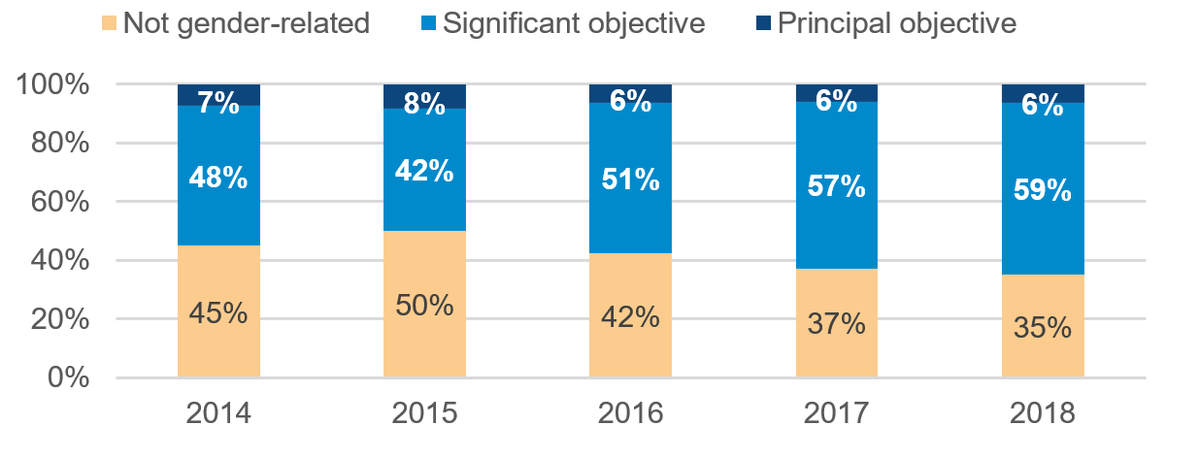

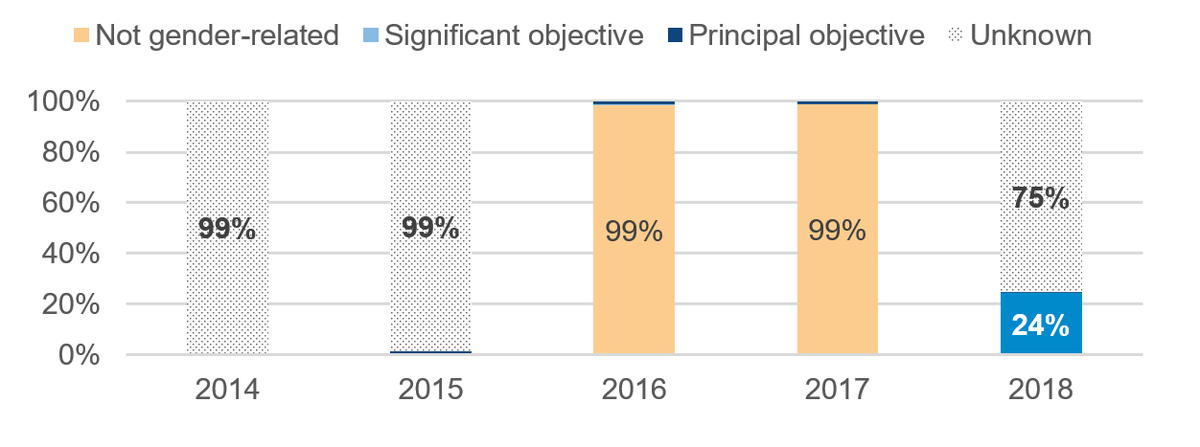

Gender equality features strongly as a priority for DFID aid, whereas for the FCO it is either not prioritised or a lack of transparent publishing about the department’s aid spending means we do not know if it is helping the progress of women and girls

When aid spending data is published, it can be marked up with a ‘gender equality marker’ showing whether that spending has gender equality as a principal or significant objective. Comparing the two departments we see DFID consistently demonstrating that gender is a priority for aid allocations. On the other hand, the FCO either spends only a small proportion of its aid on gender equality or has chosen to not make use of the marker that would enable transparency and accountability about the department’s support for gender equality.

Figure 6: Proportion of the FCO’s aid targeted to projects with a gender-equality focus

Proportion of the FCO’s aid targeted to projects with a gender-equality focus

Source: Development Initiatives based on Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC).

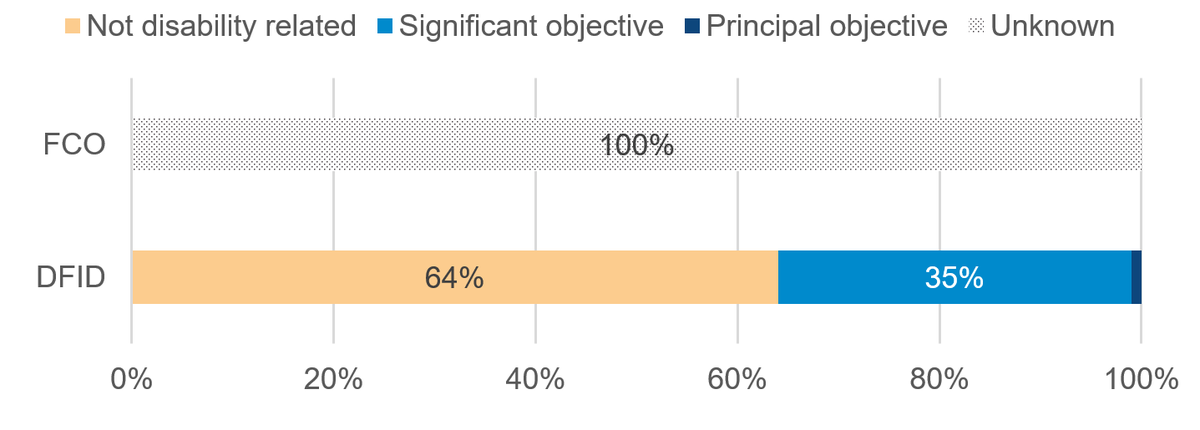

We can see that disability inclusion is a significant objective for 35% of DFID aid spending, but the FCO does not mark up its aid spending on disability, so the proportion spent is not known

Disability inclusion is a key policy priority for DFID, and the department’s aid spending is marked up so that DFID’s support for disability inclusion can be monitored and measured. The FCO did not mark up their aid spending in 2018 (when the OECD DAC disability policy marker was brought in) so it is not possible to see whether it allocated funding to disability inclusion, or to hold them to account on this important area. It is vital that DFID’s strong record on comprehensive and transparent reporting is retained by the new department after the merger.

Figure 7: FCO and DFID aid targeted to projects with a disability-inclusion focus

FCO and DFID aid targeted to projects with a disability-inclusion focus

Source: Development Initiatives based on Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC).

Note: The disability marker was first available in 2018, so there is only one year of data. The FCO did not report whether any of their projects had disability inclusion as a principal or significant objective.

DFID is a world-leader on transparency, and independent reviews suggest it is far stronger on effectiveness and value for money than the FCO

DFID has received consistently high rankings in independent assessments of aid transparency, while the FCO has struggled. Publish What You Fund, an independent assessor of aid transparency, found DFID to be the most transparent donor agency in the EU, and the third most transparent in the world in its most recent transparency index . In Publish What You Fund’s 2020 transparency review of UK government departments , the FCO was classed as ‘poor’ in 2018, rising to ‘fair’ in 2020, but still behind most other UK aid-spending departments. This is because the FCO does not publish timely or sufficiently high-quality and granular information about its projects, budgets, procurement and evaluations. We can see this evidenced in the paucity of spending tagged with the gender and disability markers, which would have enabled spending on these areas to be assessed.

Further, while the UK government has committed to publishing all aid spending to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), to a good standard, the FCO appears to be falling behind on delivering this commitment. Looking at reporting to IATI using the new Covid-19 tag, DFID has reported US$128 million and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) has reported US$6.7 million, but there is no data from the FCO. This suggests that the FCO has either not contributed to the UK’s pandemic response with aid, not published this data yet or has not used the new tag. Good-quality, timely data is critical for managing effective and rapid response to crisis.

With regard to aid effectiveness, DFID has shown strong commitment and proactive efforts to ensure value for money on UK aid, as shown in performance reviews by the Independent Commission for Aid Impact. The department was also commended by the OECD’s latest peer review of the UK , which states that they were “particularly impressed” by its efforts to balance risk-taking, transparency and value for money. There is no doubt that DFID has room for improvement, however the FCO’s track record on spending aid effectively has been heavily criticised in reviews undertaken by the UK’s National Audit Office , the UK’s Independent Commission for Aid Impact and the UK Parliament’s International Development Committee . These independent bodies have also raised concerns about the effectiveness, efficiency and value for money of programmes or funds administered out of the FCO (such as the Prosperity Fund), or where the FCO is the largest recipient (such as the Conflict, Security and Stability Fund – 69.5% of CSSF aid went to the FCO in 2018).

What could be lost in the merger?

This analysis clearly outlines the risks to the impact, effectiveness and quality of UK aid that could result from the merger. Despite increased aid spending by other government departments since 2015, DFID has ensured that UK aid remains predominantly focused on:

- Delivering for those people and places most in need, leading the UK’s global contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals and ending extreme poverty.

- Delivering aid effectively, and providing value for money, transparency and accountability to the UK taxpayer and those UK aid aims to help.

These achievements are due in no small part to the expertise and experience of staff in DFID who have made the UK a global leader in development in the last two decades. As numerous commentators and experts have pointed out, DFID and the FCO do different jobs, requiring different skills. The restructure carries with it the risk of losing vital expertise that would have significant ramifications for the effectiveness of UK aid spending, particularly the delivery of large portfolios and programmes that support and save millions of lives all over the world.

There is also significant concern that the restructure may mean a reduction in the accountability of and scrutiny applied to UK aid. Currently, UK aid is scrutinised by the International Development Committee (IDC) – which has a specific remit for DFID – the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI), the National Audit Office (NAO) and by the OECD Peer Review process. Losing the IDC as a specialist development committee would substantially reduce parliamentary scrutiny of the UK’s aid. The current Secretary of State has previously acknowledged the need for greater, coherent scrutiny of UK aid across all departments. Other committees, such as the Foreign Affairs Committee, would need to take on this scrutiny role. However, despite the BEIS, the FCO and, and the CSSF being the largest non-DFID spenders of aid in 2018 (spending 6.3%, 4.5% and 4.4% of the total respectively), it seems there have been no substantive inquiries by the committees focused on the departments’ ODA spend. This is critical in the context of the merger because, as a recent IDC inquiry pointed out, the quality of UK aid spent outside DFID appears already to be ‘eroded’ .

The merger has also raised concerns about a lack of consultation. While commitments were made to approach the Integrated Review and any subsequent possible merger with ‘proper consultation’ , as noted by the current Chair of the IDC Sarah Champion MP, this process does not appear to have been followed.

Recommendations

On the basis of the data and evidence presented above, the new department should:

- Commit to maintaining poverty reduction as the primary objective of UK aid spending, rather than just meeting the OECD’s definition for aid. This will ensure rhetoric about a continued focus on poverty is put into practice, and prove that the UK government is committed to delivering the Sustainable Development Goals and helping the 735 million people living in extreme poverty globally.

- Maintain the targeting of UK aid to the poorest countries and people in line with current DFID spending patterns. Aid allocations from DFID are substantially more focused on countries with higher levels of poverty and lower domestic resources as well as on fragile countries – this prioritisation should continue.

- Retain DFID’s clear commitment to ‘leave no one behind’ and adopt its strategies on disability and gender . This is vital to ensure a continued focus on those most likely to be left behind or already most marginalised.

- Publish high-quality data to IATI on at least a monthly basis, implement DFID’s policy of requiring organisations in receipt of UK aid to also publish where they spend funds to IATI, and maintain DFID’s ‘very good’ rating in the Aid Transparency Index.

- Ensure consistent use of key markers when reporting aid spending to the OECD DAC , including on disability and gender, to ensure transparency and accountability.

- Create and comply with updated guidelines and processes on aid effectiveness and value for money that ensure both transparent monitoring and progress.

- Retain decades of unique experience in international development held by DFID by ensuring any restructure does not result in the loss of crucial expertise in managing complex and vital development projects and programmes that save millions of lives across the world every year.

- Ensure that the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office Select Committee that will scrutinise the department’s work is composed of members combining the expertise of the existing IDC and Foreign Affairs Committee to maintain effective parliamentary scrutiny of its work across the board, and on aid spending in particular.

- Improve whole-of-government scrutiny of UK aid spending by creating a new cross-government ODA (official development assistance) committee. There is precedent for having cross-department committees, such as the Environmental Audit Committee , where responsibility lies across different government departments to ensure there is adequate scrutiny.

- Ensure the roles of ICAI and the NAO, as well as the OECD peer review process are maintained to ensure high levels of transparency and accountability on UK aid spending continue.

Downloads

Notes

-

1

The analysis in this briefing only looks at country-specific bilateral ODA.Return to source text

Related content

The power of transparency: Data is key to an effective crisis response

DI's Verity Outram and World Vision's Daniel Stevens share lessons, applicable to the coronavirus pandemic and more broadly, for how transparency and high-quality data can help humanitarian organisations, donors and advocates better respond to crises.

Coronavirus and aid data: What the latest DAC data tells us

How might the coronavirus pandemic impact aid spending? DI presents analysis of preliminary ODA (aid) data for 2019. Our briefing shows how much was given and in what form.

Countering isolationism with collaboration as we enter the decade of delivery

In the context of growing isolationism, DI's Harpinder Collacott reflects on the past few years and looks to the future, arguing that collaboration will be key to making progress in the decade of delivery.